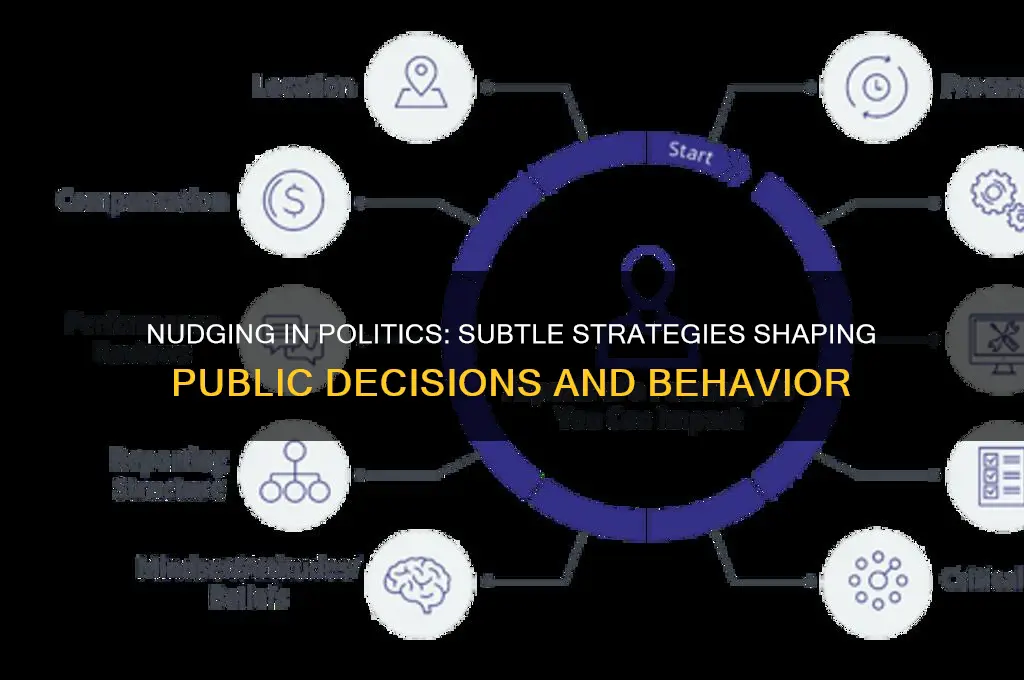

Nudging in politics refers to the application of behavioral science principles to influence public decision-making and behavior without imposing strict regulations or bans. Derived from the concept of nudge theory, popularized by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, it involves subtle, choice-architectural interventions designed to guide individuals toward making decisions that align with desired societal outcomes. In politics, nudges are often employed to encourage voter participation, promote public health initiatives, or foster environmentally friendly behaviors. Unlike traditional policy tools that rely on mandates or incentives, nudges preserve individual autonomy while leveraging insights from psychology and economics to shape collective actions. This approach has gained traction among policymakers seeking cost-effective and non-coercive ways to address complex societal challenges.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A behavioral science concept using subtle cues to influence decisions without coercion. |

| Origin | Coined by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in "Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness" (2008). |

| Purpose | To guide public behavior toward socially beneficial outcomes while preserving individual choice. |

| Key Principles | - Defaults, framing, simplification, social proof, and timing. |

| Examples in Politics | - Auto-enrollment in voter registration. |

| - Simplifying tax forms to increase compliance. | |

| - Using social norms to encourage energy conservation. | |

| Ethical Considerations | - Transparency in implementation. |

| - Avoiding manipulation or exploitation of cognitive biases. | |

| Effectiveness | Proven successful in areas like healthcare, taxation, and environmental policy. |

| Criticisms | - Potential for paternalism. |

| - Risk of undermining individual autonomy. | |

| Global Adoption | Widely used in governments (e.g., UK’s Behavioural Insights Team, Obama administration). |

| Recent Trends | Increased focus on digital nudges (e.g., online platforms for civic engagement). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Behavioral Insights in Policy Making: Using psychology to design policies that influence citizen behavior subtly

- Nudge Units in Governments: Teams applying nudges to improve public service efficiency and outcomes

- Ethical Concerns of Nudging: Debates on manipulation, consent, and transparency in political nudges

- Nudges in Voter Turnout: Strategies to increase participation without coercion or incentives

- Nudging for Public Health: Policies encouraging healthier choices through subtle behavioral interventions

Behavioral Insights in Policy Making: Using psychology to design policies that influence citizen behavior subtly

Nudging in politics leverages behavioral science to shape citizen actions without coercion, often through subtle environmental or structural changes. For instance, automatically enrolling employees into retirement savings plans, with an opt-out option, increases participation rates by 30-50% compared to opt-in systems. This "default effect" illustrates how small design tweaks can yield significant behavioral shifts, making it a powerful tool for policymakers aiming to improve public welfare.

To implement behavioral insights effectively, policymakers must first identify the target behavior and its underlying psychological barriers. For example, if the goal is to reduce energy consumption, understanding that social norms influence behavior can lead to interventions like displaying neighborhood energy usage comparisons. Studies show households receiving such feedback reduce consumption by 2-5% on average. Pairing this with pre-commitment strategies, such as allowing citizens to pledge energy-saving goals, amplifies results, demonstrating the importance of combining multiple behavioral levers for maximum impact.

However, the ethical implications of nudging cannot be overlooked. Critics argue that such interventions manipulate rather than empower citizens, particularly when transparency is lacking. To mitigate this, policymakers should ensure nudges are clearly justified, evidence-based, and designed to benefit the public good. For instance, framing a tax payment reminder with a message emphasizing collective societal contributions ("Your taxes help build schools") increases compliance by 15% compared to neutral language, balancing persuasion with ethical considerations.

A comparative analysis reveals that nudging is most effective in domains with high decision complexity or inertia, such as healthcare and finance. For example, simplifying health insurance choice architecture by categorizing plans based on consumer profiles increases enrollment by 20%. Conversely, in areas requiring deep behavioral change, such as smoking cessation, nudges alone are insufficient; they must complement traditional policies like taxation or education. This highlights the need for a layered approach, where nudges serve as catalysts rather than standalone solutions.

In practice, successful nudging requires rigorous testing and iteration. Pilot programs should measure not only immediate outcomes but also long-term behavioral shifts. For instance, a UK trial using text message reminders for tax payments increased on-time submissions by 34% among younger demographics (18-35), but had minimal impact on older citizens, underscoring the need for age-specific tailoring. By embedding behavioral insights into policy design and evaluation, governments can craft interventions that are both effective and respectful of citizen autonomy.

Crafting Persuasive Political Narratives: The Art of Speechwriting Explained

You may want to see also

Nudge Units in Governments: Teams applying nudges to improve public service efficiency and outcomes

Governments worldwide are increasingly turning to behavioral science to enhance public service delivery. At the heart of this shift are "Nudge Units"—dedicated teams that apply insights from behavioral economics to design interventions aimed at improving citizen outcomes. These units operate on the principle that small, subtle changes in how choices are presented can lead to significant shifts in behavior, often at minimal cost. For instance, the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team, often called the world’s first Nudge Unit, has implemented strategies that increased tax compliance by simplifying communication and leveraging social norms, recovering millions in unpaid taxes annually.

Establishing a Nudge Unit requires a structured approach. First, identify key policy areas where behavioral interventions could yield high impact, such as healthcare adherence, energy conservation, or tax compliance. Second, assemble a multidisciplinary team of behavioral scientists, data analysts, and policy experts to design and test interventions. Third, pilot these interventions on a small scale, using randomized controlled trials to measure effectiveness. For example, a nudge to increase organ donor registrations in the U.S. involved changing the default setting on driver’s license applications, resulting in a 40% increase in sign-ups. Caution must be taken to avoid ethical pitfalls, such as manipulating vulnerable populations or infringing on individual autonomy.

The success of Nudge Units hinges on their ability to balance scientific rigor with practical implementation. One effective strategy is to frame messages in ways that resonate with citizens’ values and motivations. For instance, a campaign to reduce energy consumption in Singapore used social comparison, informing households of their energy use relative to neighbors, leading to a 2% reduction in usage. Another tactic is to simplify complex processes; the Australian government streamlined tax filing by pre-filling forms with existing data, increasing on-time submissions by 15%. These examples underscore the importance of tailoring nudges to cultural and contextual nuances.

Critics argue that Nudge Units risk overstepping their role, potentially undermining citizen trust if interventions are perceived as manipulative. To mitigate this, transparency is key. Governments should clearly communicate the purpose and methodology of nudges, ensuring citizens understand how and why their behavior is being influenced. Additionally, Nudge Units must prioritize long-term behavioral change over short-term gains, avoiding the temptation to exploit cognitive biases for quick wins. When executed ethically, these units can serve as powerful tools for fostering public good, demonstrating that small changes in policy design can yield outsized benefits for society.

Gracefully Declining Gifts: A Guide to Polite Refusal and Boundaries

You may want to see also

Ethical Concerns of Nudging: Debates on manipulation, consent, and transparency in political nudges

Nudging, as a behavioral science technique, has been increasingly employed in politics to subtly guide citizens’ decisions without restricting their choices. While its effectiveness in shaping public behavior is evident—from boosting voter turnout to encouraging tax compliance—its ethical implications remain fiercely contested. At the heart of these debates are concerns about manipulation, consent, and transparency, which challenge the very foundation of democratic principles.

Consider the manipulation debate: a nudge, by design, exploits cognitive biases to influence behavior. For instance, framing a policy as a “default option” can significantly alter public response, as seen in organ donation systems where opt-out schemes yield higher participation rates. Critics argue that such tactics undermine rational decision-making, effectively coercing individuals into choices they might not otherwise make. Proponents counter that nudges merely simplify complex decisions, but the line between assistance and manipulation blurs when the intent is political. A nudge that subtly favors a government’s agenda, for example, raises questions about whether it serves the public good or partisan interests.

Consent is another ethical flashpoint. Unlike explicit policies, nudges operate below the threshold of conscious awareness, making it difficult for individuals to opt out or even recognize they are being influenced. Take the use of social norms in political campaigns: messages like “9 out of 10 citizens in your area voted” leverage peer pressure to drive turnout. While effective, this approach circumvents informed consent, treating citizens as passive subjects rather than active participants in democracy. This lack of agency conflicts with liberal ideals of autonomy, prompting calls for stricter regulations to ensure nudges are deployed ethically.

Transparency further complicates the ethical landscape. Political nudges are often embedded in everyday environments—from ballot designs to public service announcements—making them nearly invisible. Without clear disclosure, citizens cannot evaluate the intent behind these interventions. For instance, a nudge encouraging participation in a government program might appear neutral but could be designed to favor specific demographic groups. Transparency not only fosters trust but also allows for public scrutiny, ensuring nudges align with democratic values rather than serving as tools of covert control.

To navigate these ethical challenges, policymakers must adopt a three-pronged approach: first, establish clear guidelines distinguishing between benign nudges and manipulative tactics. Second, implement mechanisms for informed consent, such as opt-in systems or explicit notifications when nudges are in play. Finally, prioritize transparency by publicly documenting the rationale, design, and outcomes of nudge-based interventions. By addressing these concerns, nudging can be harnessed as a force for good, balancing behavioral insights with the principles of a fair and open society.

Monopoly: Economic Powerhouse or Political Puppet Master?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nudges in Voter Turnout: Strategies to increase participation without coercion or incentives

Voter turnout is a critical metric for democratic health, yet many democracies struggle with declining participation rates. Nudging, a concept rooted in behavioral economics, offers a subtle yet effective approach to increasing voter turnout without resorting to coercion or financial incentives. By leveraging small, strategic changes in the choice architecture, policymakers can encourage citizens to act in their own and society’s best interest. For instance, sending personalized text message reminders about polling locations and hours has been shown to increase turnout by 2-3 percentage points, particularly among younger voters aged 18-29, who often face barriers like lack of information or time constraints.

One effective nudge strategy involves simplifying the voting process. Research indicates that complexity is a significant deterrent to voting, especially for first-time voters. Implementing pre-filled registration forms or providing clear, step-by-step guides can reduce cognitive load and make voting feel less daunting. In Estonia, for example, the introduction of an e-voting system streamlined participation, contributing to a 44% turnout rate in the 2019 parliamentary elections. Such digital solutions not only cater to tech-savvy younger demographics but also ensure accessibility for elderly voters who may struggle with physical polling stations.

Another powerful nudge is social proof, which leverages the human tendency to follow the actions of others. Campaigns that highlight high turnout rates or share messages like “85% of your neighbors voted” can create a sense of civic duty. A study in the U.S. found that voters were 1.8% more likely to participate when informed that their voting behavior would be publicly shared (though anonymized). However, caution must be exercised to avoid shaming non-voters, as this can backfire. Instead, framing the message positively—such as celebrating community participation—yields better results.

Timing and salience also play crucial roles in nudging voter turnout. Sending reminders 2-3 days before an election, rather than weeks in advance, increases their effectiveness by aligning with voters’ immediate decision-making processes. Additionally, coupling reminders with practical information, such as polling station wait times or weather forecasts, can further motivate action. For instance, a pilot program in Denmark that provided real-time updates on polling station crowds saw a 5% increase in turnout among recipients.

While nudges are powerful, their ethical implementation is paramount. Transparency is key—citizens should understand why and how they are being nudged. Policymakers must also avoid manipulation by ensuring nudges align with genuine public interest. For example, pre-checked boxes on voter registration forms, while effective, can feel coercive if not clearly explained. Striking this balance requires continuous evaluation and feedback from diverse voter groups to ensure strategies remain inclusive and respectful of individual autonomy.

In conclusion, nudges offer a promising toolkit for boosting voter turnout without resorting to heavy-handed tactics. By simplifying processes, leveraging social norms, optimizing timing, and prioritizing ethics, policymakers can create an environment that encourages participation. These strategies, when tailored to specific demographics and contexts, have the potential to revitalize democratic engagement and strengthen the fabric of civic life.

Understanding Political Outreach: Strategies, Impact, and Community Engagement

You may want to see also

Nudging for Public Health: Policies encouraging healthier choices through subtle behavioral interventions

Public health challenges often stem from individual behaviors that, when aggregated, lead to widespread issues like obesity, smoking-related diseases, and vaccine hesitancy. Nudging, a concept rooted in behavioral economics, offers a non-coercive approach to steer people toward healthier choices by subtly altering their decision-making environment. Unlike traditional policies that mandate or restrict, nudges preserve individual autonomy while leveraging cognitive biases to encourage better outcomes. For instance, placing fruit at eye level in school cafeterias increases its selection over less healthy options, demonstrating how small environmental changes can yield significant behavioral shifts.

Consider the implementation of nudges in vaccination campaigns. A simple text message reminding parents of their child’s immunization schedule, coupled with a map to the nearest clinic, can dramatically improve uptake rates. This approach, tested in several countries, combines convenience with a gentle reminder, addressing both forgetfulness and logistical barriers. Similarly, framing vaccine benefits in terms of "protecting your family" rather than "avoiding disease" taps into social norms and emotional motivations, making the choice more personally resonant. Such strategies highlight how nudges can bridge the gap between public health goals and individual behavior.

However, designing effective nudges requires careful consideration of context and ethics. For example, a nudge encouraging reduced sugar intake might involve labeling products with teaspoons of sugar instead of grams, making the quantity more tangible. Yet, this must be paired with education to avoid confusion or mistrust. Additionally, nudges should not disproportionately target vulnerable populations or exploit psychological vulnerabilities. Policymakers must balance the desire for positive outcomes with respect for individual agency, ensuring interventions are transparent and fair.

A comparative analysis reveals that nudges are most effective when integrated into broader policy frameworks. For instance, while a nudge to promote stair use over elevators (e.g., placing motivational signs) can increase physical activity, its impact is amplified when combined with urban planning that prioritizes walkable spaces. Similarly, nudges to reduce salt intake in restaurants (e.g., defaulting to low-sodium options) work best alongside industry regulations capping salt content in processed foods. This synergy between nudges and structural changes underscores their role as complementary tools in public health.

In practice, implementing nudges requires collaboration across sectors and a commitment to evidence-based design. Pilot programs should test interventions in real-world settings, measuring outcomes like behavior change, cost-effectiveness, and public acceptance. For example, a nudge to increase water consumption in schools might involve installing water stations with counters displaying the number of bottles saved from landfills. Such initiatives not only promote health but also foster environmental awareness. By iterating based on data, policymakers can refine nudges to maximize their impact while minimizing unintended consequences.

Ultimately, nudging for public health represents a nuanced approach to behavior change, one that respects individual freedom while addressing collective challenges. When thoughtfully designed and ethically deployed, these subtle interventions can transform environments in ways that make healthier choices the easier, more appealing default. As societies grapple with complex health issues, nudges offer a powerful yet unobtrusive tool to guide populations toward better outcomes.

Understanding Liberal Left-Wing Politics: Ideologies, Policies, and Societal Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Nudging in politics refers to the application of behavioral science principles to influence citizen behavior or decision-making without coercion. It involves subtle, indirect suggestions or changes in the choice architecture to encourage desired outcomes, such as voting, tax compliance, or healthier lifestyles.

Traditional policy-making often relies on laws, regulations, or financial incentives to achieve goals. Nudging, on the other hand, focuses on small, low-cost interventions that guide behavior without restricting choices or imposing penalties, making it a more flexible and less intrusive approach.

A common example is sending personalized reminders to citizens to vote or pay taxes. For instance, a text message reminding someone to vote, along with polling station information, can significantly increase voter turnout without forcing participation.

The ethics of nudging are debated. Proponents argue it respects individual autonomy while promoting societal benefits. Critics, however, worry about potential manipulation or lack of transparency. Ethical nudging requires clear intentions, informed consent, and a focus on public welfare rather than partisan interests.