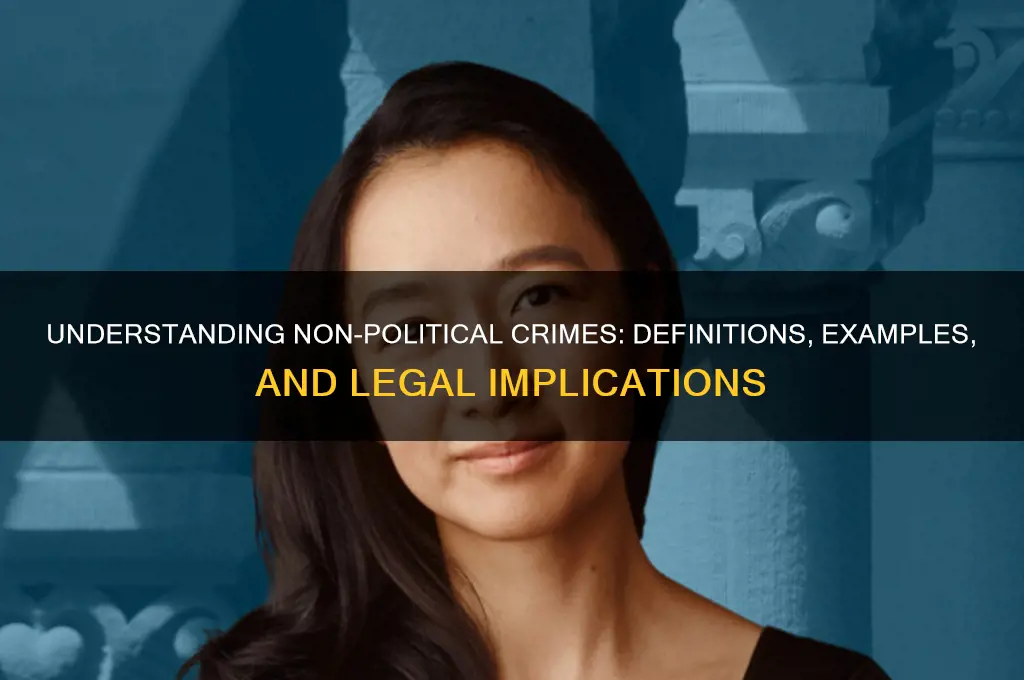

Non-political crimes refer to offenses that are not motivated by political ideologies, goals, or opposition to a government or ruling system. These crimes are typically driven by personal, financial, or social factors rather than a desire to challenge or influence political power. Examples include theft, assault, fraud, and drug trafficking, which are generally prosecuted under standard criminal law rather than being categorized as acts of political dissent or rebellion. Understanding the distinction between political and non-political crimes is crucial, as it shapes legal responses, penalties, and societal perceptions of the offender's intent and actions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Crimes not motivated by political ideology, goals, or opposition to a government. |

| Examples | Theft, robbery, assault, fraud, drug trafficking, domestic violence, etc. |

| Motivation | Personal gain, greed, revenge, passion, mental health issues, or accident. |

| Target | Individuals, private property, or businesses, not political entities. |

| Intent | Typically lacks intent to challenge or influence political systems. |

| Legal Classification | Classified under criminal law, not political or state security laws. |

| Punishment | Penalties based on criminal codes, not political repression. |

| International Recognition | Not recognized as a distinct category in international law. |

| Context | Occurs in any political system, regardless of governance type. |

| Distinction from Political Crimes | Lacks political objective or connection to state authority. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- White-collar crimes: Corporate fraud, embezzlement, insider trading, and other financially motivated non-political offenses

- Organized crime: Drug trafficking, human trafficking, and racketeering without political motives or goals

- Violent crimes: Murder, assault, robbery, and other acts of violence unrelated to politics

- Property crimes: Theft, burglary, vandalism, and arson committed for personal gain, not political reasons

- Cybercrimes: Hacking, identity theft, and online fraud without political agendas or objectives

White-collar crimes: Corporate fraud, embezzlement, insider trading, and other financially motivated non-political offenses

White-collar crimes, though lacking the dramatic flair of heists or robberies, inflict profound economic damage and erode public trust in institutions. Unlike political crimes, which challenge state authority or advocate for ideological change, these offenses are driven purely by financial gain. Corporate fraud, embezzlement, and insider trading exemplify this category, often exploiting complex financial systems and positions of trust for personal enrichment.

Consider corporate fraud, where executives manipulate financial statements to deceive investors and regulators. Enron’s collapse in 2001 remains a stark example, with executives inflating profits by billions, leading to bankruptcy and thousands of job losses. Embezzlement, another common white-collar crime, involves the misappropriation of funds entrusted to an individual. A 2020 report by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners found that the median loss from embezzlement cases was $150,000, with small businesses disproportionately affected due to weaker internal controls.

Insider trading, while less frequent, garners significant attention due to its high-profile nature. This occurs when individuals trade securities based on non-public information, violating fairness in financial markets. The case of Galleon Group founder Raj Rajaratnam, sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2011, highlights the severity of such offenses. These crimes are non-political because they do not seek to challenge government policies or promote a specific agenda; instead, they exploit systemic vulnerabilities for personal benefit.

To combat these offenses, organizations must implement robust internal controls, such as segregation of duties, regular audits, and whistleblower protections. For instance, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 mandates stricter financial reporting standards for public companies, reducing the likelihood of fraud. Individuals should also remain vigilant, scrutinizing financial statements and reporting suspicious activities to regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Ultimately, white-collar crimes underscore the need for ethical leadership and regulatory oversight. While they may lack the overt violence of other crimes, their impact on economies and livelihoods is undeniable. By understanding their mechanisms and consequences, society can better safeguard against these financially motivated offenses.

Is Cambodia Politically Stable? Analyzing Its Current Governance and Future Outlook

You may want to see also

Organized crime: Drug trafficking, human trafficking, and racketeering without political motives or goals

Organized crime, stripped of political agendas, thrives in the shadows of society, driven purely by profit and power. Drug trafficking, human trafficking, and racketeering are its cornerstone enterprises, each operating with ruthless efficiency and devastating consequences. These crimes are not acts of rebellion or ideological warfare; they are calculated business ventures exploiting vulnerabilities in systems and people.

Understanding their mechanics is crucial for dismantling their grip on communities.

Consider drug trafficking. It’s a global industry worth over $400 billion annually, according to the UNODC. Cartels and syndicates control every stage, from production in remote labs to street-level distribution. Heroin, cocaine, and synthetic opioids like fentanyl are moved through intricate networks, often disguised in legitimate cargo. The profit margins are staggering: a kilogram of cocaine, costing around $2,000 in South America, can fetch $30,000 in the U.S. This economic incentive fuels violence, corruption, and addiction, leaving trails of devastation in its wake.

Unlike politically motivated insurgencies, drug trafficking’s sole aim is financial gain, making it a non-political crime with profoundly political consequences.

Human trafficking, another pillar of organized crime, operates on a similarly profit-driven model. The International Labour Organization estimates that 25 million people are trapped in forced labor, sexual exploitation, or domestic servitude. Victims are lured with false promises of jobs or better lives, then coerced through violence, debt bondage, or psychological manipulation. A trafficked individual can generate $200,000 annually for their exploiters, making it a highly lucrative enterprise. Unlike political kidnappings or hostage-taking, human trafficking is purely transactional, exploiting human vulnerability for monetary gain. Its victims are often invisible, hidden in plain sight, making it a pervasive yet underreported crime.

Racketeering, the third leg of this triad, involves infiltrating legitimate businesses or creating fronts to launder money and exert control. From protection rackets to counterfeit goods, organized crime groups use intimidation and fraud to siphon profits. For instance, a construction company might be forced to pay a "fee" to avoid vandalism, or a restaurant could be extorted into buying subpar supplies at inflated prices. These schemes undermine economies, distort markets, and erode public trust. Unlike political corruption aimed at regime change, racketeering seeks only to enrich its perpetrators, often at the expense of law-abiding citizens and businesses.

Combating these non-political crimes requires a multi-pronged approach. Law enforcement must target the financial infrastructure of organized crime, freezing assets and disrupting money laundering networks. International cooperation is essential, as these crimes often cross borders. Communities play a vital role too, by recognizing signs of trafficking, reporting suspicious activities, and supporting victims. Education campaigns can raise awareness about the dangers of drug abuse and the tactics used by traffickers. Ultimately, dismantling organized crime demands not just legal action but a collective effort to address the socioeconomic conditions that make exploitation profitable. Without political motives to cloud the issue, the focus remains squarely on protecting lives and livelihoods.

Understanding Mansfield Politics: A Comprehensive Guide for Engaged Citizens

You may want to see also

Violent crimes: Murder, assault, robbery, and other acts of violence unrelated to politics

Violent crimes that lack political motivation—murder, assault, robbery, and similar acts—are driven by personal, financial, or emotional factors rather than ideological agendas. Unlike politically charged offenses, these crimes target individuals or groups without aiming to challenge government authority, advance a political cause, or reshape societal structures. For instance, a robbery motivated by financial desperation or a murder stemming from a personal dispute falls into this category, as the intent is not to make a political statement but to fulfill immediate, often self-serving, objectives.

Analyzing these crimes reveals a stark contrast to their political counterparts. While political violence often seeks to provoke systemic change or retaliate against perceived oppression, non-political violent crimes are typically rooted in individual grievances, mental health issues, or socioeconomic pressures. Assaults driven by road rage, robberies fueled by addiction, or murders resulting from domestic conflicts exemplify this. Law enforcement agencies treat these cases differently, focusing on individual culpability rather than broader ideological networks, making prevention and prosecution more localized and person-centered.

From a practical standpoint, addressing non-political violent crimes requires multifaceted strategies. Community-based initiatives, such as mental health support programs, conflict resolution training, and economic empowerment schemes, can mitigate underlying causes. For example, cities with robust youth intervention programs have seen reductions in assault rates among adolescents aged 15–24. Similarly, targeted policing in high-crime areas, coupled with rehabilitation efforts for offenders, can disrupt cycles of violence. Victims, too, benefit from accessible resources like counseling services and legal aid, which help them recover and reduce the likelihood of retaliatory acts.

Comparatively, while political crimes often demand international cooperation and policy reforms, non-political violent crimes call for hyper-local solutions. Schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods become critical battlegrounds. For instance, implementing bystander intervention training in schools can empower students to de-escalate conflicts before they turn violent. Employers can introduce stress management workshops to address workplace aggression. These measures, though small in scale, collectively create safer environments by tackling the root causes of violence at the individual and community levels.

Ultimately, understanding non-political violent crimes as distinct from their politically motivated counterparts allows for more effective intervention. By focusing on personal triggers and community dynamics, societies can reduce the incidence of such crimes without conflating them with broader political unrest. This tailored approach not only enhances public safety but also ensures that resources are allocated efficiently, addressing the specific needs of those most at risk.

Kindly Declining Advances: A Guide to Rejecting Guys Politely

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Property crimes: Theft, burglary, vandalism, and arson committed for personal gain, not political reasons

Property crimes, such as theft, burglary, vandalism, and arson, are often motivated by personal gain rather than political ideology. These offenses target tangible assets, from cash and electronics to real estate and vehicles, with the primary intent of financial enrichment or material acquisition. Unlike politically motivated crimes, which seek to challenge or influence governmental structures, property crimes are driven by individual desires for wealth, revenge, or thrill-seeking. For instance, a burglar breaking into a home to steal jewelry is acting out of personal greed, not to make a political statement.

Analyzing the impact of these crimes reveals their far-reaching consequences. Victims of property crimes often suffer financial losses, emotional distress, and a diminished sense of security. Insurance claims for stolen goods or damaged property can skyrocket, affecting premiums for entire communities. Moreover, businesses targeted by theft or vandalism may face operational disruptions, leading to lost revenue and job instability. Law enforcement agencies allocate significant resources to investigate these crimes, diverting attention from other critical issues. Understanding this impact underscores the importance of prevention and swift prosecution.

Preventing property crimes requires a multi-faceted approach. Homeowners can invest in security systems, motion-activated lights, and reinforced locks to deter burglars. Businesses should implement inventory tracking, employee training, and surveillance cameras to minimize theft. Communities can organize neighborhood watch programs to monitor suspicious activity and foster collective vigilance. Additionally, addressing root causes, such as economic inequality or lack of opportunities, can reduce the incentive for individuals to commit these crimes. Practical steps like these empower individuals and communities to protect their assets proactively.

Comparing property crimes to politically motivated offenses highlights their distinct nature. While political crimes, such as terrorism or sabotage, aim to destabilize governments or advance ideologies, property crimes are inherently self-serving. For example, arson committed to collect insurance money differs fundamentally from burning a building to protest a policy. This distinction is crucial for legal systems, as it influences sentencing, rehabilitation efforts, and public perception. Recognizing these differences ensures that responses to crime are tailored to their underlying motivations.

In conclusion, property crimes committed for personal gain represent a pervasive challenge with tangible solutions. By understanding their motivations, impacts, and preventive measures, individuals and communities can mitigate risks effectively. While these crimes lack the ideological underpinnings of political offenses, their consequences are no less significant. Addressing them requires a combination of personal responsibility, community engagement, and systemic support to safeguard both property and peace of mind.

NRA's Political Spending: Unveiling the Financial Influence and Impact

You may want to see also

Cybercrimes: Hacking, identity theft, and online fraud without political agendas or objectives

Cybercrimes like hacking, identity theft, and online fraud often lack political motives, driven instead by financial gain, personal vendettas, or sheer opportunism. Unlike politically motivated attacks targeting governments or ideologies, these crimes focus on exploiting vulnerabilities for immediate benefit. For instance, a hacker might breach a small business’s database to steal credit card information, not to destabilize a regime but to sell the data on the dark web. This distinction is crucial: while political cybercrimes aim to influence or disrupt systems, non-political cybercrimes are transactional, often leaving victims with financial or emotional damage rather than societal upheaval.

Consider identity theft, a crime that thrives in the digital age. Perpetrators steal personal information—Social Security numbers, bank details, or login credentials—to impersonate victims for financial gain. Unlike a politically motivated attack, which might aim to expose corruption or silence dissent, identity theft is purely exploitative. For example, a fraudster might use a stolen identity to open credit accounts, leaving the victim with ruined credit scores and legal battles. Protecting against this requires vigilance: regularly monitor bank statements, use strong, unique passwords, and enable two-factor authentication wherever possible. These steps, while not foolproof, significantly reduce risk.

Online fraud, another non-political cybercrime, often leverages psychological manipulation rather than technical sophistication. Phishing scams, romance scams, and fake investment schemes prey on trust and urgency. For instance, a scammer might pose as a tech support agent, convincing a victim to grant remote access to their computer under the guise of fixing a non-existent issue. The goal? Steal sensitive data or install malware. Unlike politically motivated disinformation campaigns, these scams are about quick profits. To avoid falling victim, educate yourself on common tactics: be skeptical of unsolicited messages, verify requests independently, and never share sensitive information without confirming the requester’s identity.

Comparing these crimes to their politically motivated counterparts highlights their distinct nature. While a politically driven hacker might target a government agency to leak classified information, a non-political hacker targets individuals or businesses for financial gain. The tools and techniques may overlap—both use malware, phishing, or social engineering—but the intent diverges sharply. This difference shapes how we prevent and respond to these crimes. For non-political cybercrimes, the focus should be on individual and organizational security measures: employee training, robust cybersecurity protocols, and public awareness campaigns. By understanding this distinction, we can tailor strategies to address the root causes and mitigate risks effectively.

Understanding Political Diversity: Exploring Varied Ideologies and Perspectives in Society

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A non-political crime is an offense that is not motivated by political ideology, goals, or opposition to a government. It typically involves acts such as theft, assault, fraud, or other criminal activities that are driven by personal, financial, or social reasons rather than political objectives.

Yes, a crime can be considered non-political even if it impacts government or public institutions, as long as the intent behind the act is not politically motivated. For example, embezzling funds from a government agency for personal gain is a non-political crime, whereas sabotaging the same agency to protest government policies would be considered political.

Legal systems differentiate between political and non-political crimes by examining the intent, context, and motivation behind the act. If the crime is driven by political beliefs, aims to influence government policies, or targets the state for ideological reasons, it is classified as political. Otherwise, it is treated as a non-political crime, subject to standard criminal laws and penalties.

![Criminal Law and Its Processes: Cases and Materials [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook) (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61p34wz6jxL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Criminal Law: Cases and Materials [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61mzAfQN7fL._AC_UL320_.jpg)