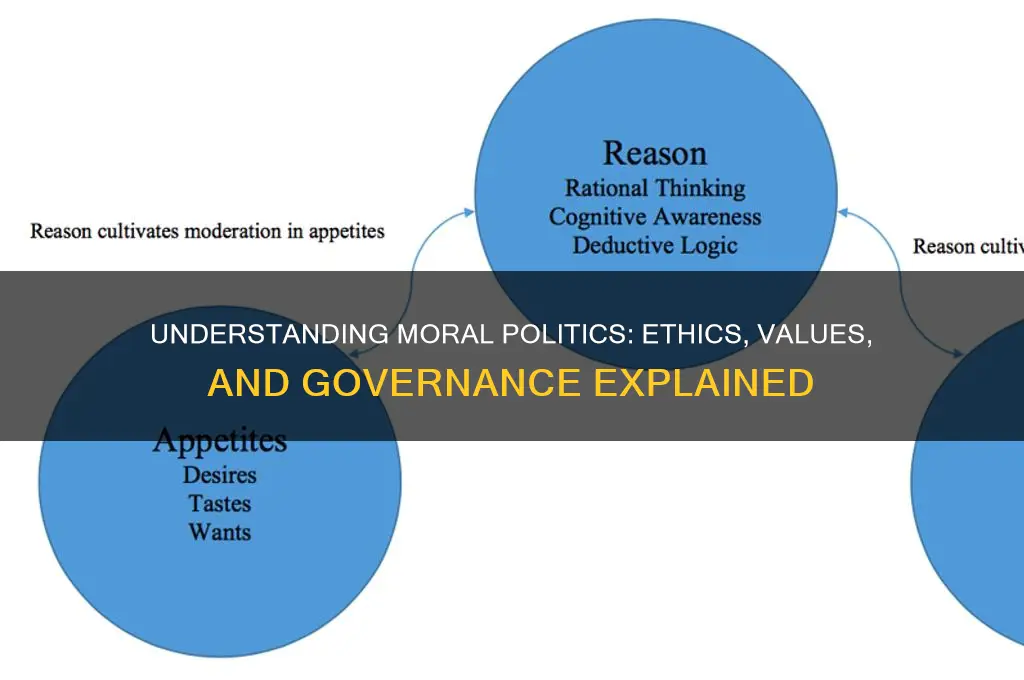

Moral politics refers to the intersection of ethics and political ideology, where individuals and groups frame political issues through the lens of their moral values and principles. Rooted in deeply held beliefs about right and wrong, fairness, and justice, moral politics shapes how people perceive policies, candidates, and societal challenges. It often divides political landscapes into competing moral frameworks, such as individualism versus communitarianism or liberty versus equality, influencing public discourse, policy debates, and voter behavior. Understanding moral politics is crucial for comprehending why certain issues resonate emotionally and why political polarization persists, as it highlights how moral convictions drive political identities and actions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Empathy and Compassion | Prioritizing the well-being of all individuals, especially marginalized groups. |

| Justice and Fairness | Ensuring equal treatment, rights, and opportunities for everyone. |

| Integrity and Honesty | Upholding transparency, accountability, and ethical behavior in governance. |

| Inclusivity and Diversity | Promoting policies that respect and celebrate differences in society. |

| Sustainability | Balancing present needs with future generations through environmental stewardship. |

| Accountability | Holding leaders and institutions responsible for their actions and decisions. |

| Participation and Democracy | Encouraging active citizen engagement in political processes. |

| Non-Violence | Resolving conflicts through dialogue and peaceful means. |

| Social Responsibility | Addressing systemic inequalities and fostering collective welfare. |

| Global Solidarity | Advocating for international cooperation and human rights beyond borders. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of ethics in policy-making: How ethical principles guide political decisions and shape public policies

- Moral foundations of ideologies: The underlying moral values driving conservative, liberal, and other political ideologies

- Justice and equality debates: Discussions on fairness, rights, and equitable distribution in political systems

- Moral dilemmas in governance: Challenges leaders face when balancing competing ethical priorities in decision-making

- Culture’s influence on morality: How societal norms and cultural beliefs shape political morality and behavior

Role of ethics in policy-making: How ethical principles guide political decisions and shape public policies

Ethical principles serve as the backbone of policy-making, ensuring that political decisions align with societal values and moral standards. For instance, the principle of justice demands that policies be fair and equitable, distributing resources and opportunities without bias. Consider healthcare policy: ethical frameworks like utilitarianism might prioritize maximizing overall health outcomes, while deontological ethics could emphasize individual rights to access care. These principles are not abstract; they directly influence whether a government funds universal healthcare or subsidizes private insurance, shaping public health disparities in tangible ways.

To integrate ethics into policy-making, decision-makers must follow a structured approach. First, identify the ethical principles at stake—such as fairness, autonomy, or harm reduction. Second, assess how proposed policies align with these principles through cost-benefit analyses or stakeholder consultations. For example, a policy to raise the minimum wage must balance economic growth (utility) with the moral imperative to reduce poverty (justice). Third, implement safeguards like transparency and accountability to ensure ethical compliance. Practical tools include ethics committees, public feedback mechanisms, and impact assessments tailored to specific demographics, such as low-income families or elderly populations.

A comparative analysis reveals how ethical principles differ across cultures and political systems, yet remain central to policy-making. In Scandinavian countries, policies rooted in egalitarian ethics prioritize social welfare, resulting in robust public services and low inequality. Contrastingly, libertarian-leaning nations emphasize individual autonomy, often leading to deregulation and private sector dominance. These divergent approaches highlight the role of ethics in shaping policy outcomes. For policymakers, understanding these cultural nuances is critical when designing policies with global implications, such as climate agreements or trade deals.

Persuasively, the absence of ethical considerations in policy-making can lead to systemic failures and public distrust. Take the case of environmental policies: without a commitment to intergenerational equity, governments may prioritize short-term economic gains over long-term ecological sustainability. This not only harms future generations but also erodes public trust in institutions. To avoid such pitfalls, policymakers must embed ethical principles into every stage of decision-making, from problem identification to implementation. Practical steps include mandating ethical training for officials, incorporating ethical criteria into policy evaluations, and fostering public dialogue on moral dilemmas in policy design.

Descriptively, ethical policy-making transforms abstract ideals into concrete actions that improve lives. For example, a policy guided by the principle of dignity might mandate accessible public transportation for disabled individuals, ensuring their autonomy and inclusion. Similarly, an ethics-driven approach to education could prioritize funding for underserved schools, addressing systemic inequalities. These examples illustrate how ethical principles, when applied thoughtfully, can create policies that are not only morally sound but also socially impactful. By anchoring decisions in ethics, policymakers can navigate complex challenges while upholding the common good.

Political Interference: How Power Struggles Undermine Utility Services and Progress

You may want to see also

Moral foundations of ideologies: The underlying moral values driving conservative, liberal, and other political ideologies

Political ideologies are not merely policy prescriptions; they are deeply rooted in moral foundations that shape how individuals and groups perceive right and wrong. Conservatives, for instance, often prioritize moral values such as loyalty, authority, and sanctity. These values manifest in policies that emphasize national unity, respect for tradition, and adherence to established norms. For example, support for strong borders or opposition to rapid social change can be traced back to a moral framework that values order and stability. Understanding these underpinnings reveals why certain issues resonate more strongly with conservative voters, offering a lens to predict their political behavior.

Liberals, on the other hand, tend to emphasize fairness, care, and liberty as their moral cornerstones. Policies advocating for social justice, equality, and individual rights are direct expressions of these values. Take, for instance, the push for universal healthcare or progressive taxation—these initiatives stem from a moral commitment to reducing suffering and ensuring equal opportunities. By framing liberal ideology through its moral foundations, one can see how it appeals to those who prioritize empathy and inclusivity. This perspective also highlights why liberals often clash with conservatives, as their moral priorities frequently diverge.

Beyond the conservative-liberal spectrum, other ideologies like libertarianism and socialism have distinct moral foundations. Libertarians champion individual freedom and self-reliance, viewing government intervention as a moral infringement on personal autonomy. Socialists, meanwhile, prioritize collective well-being and economic equality, often grounding their beliefs in a moral imperative to address systemic injustices. For practical application, consider how these moral frameworks influence policy debates: libertarians might oppose regulations on principle, while socialists advocate for wealth redistribution as a moral duty. Recognizing these differences allows for more nuanced dialogue across ideological divides.

To engage effectively in moral politics, it’s essential to identify the moral foundations driving one’s own and others’ beliefs. A useful exercise is to analyze a contentious policy—say, gun control—through this lens. Conservatives may oppose restrictions based on values of personal responsibility and protection, while liberals support them out of concern for public safety and care. By mapping these moral underpinnings, individuals can move beyond surface-level disagreements to address the core values at stake. This approach fosters greater understanding and can lead to more productive political discourse.

Finally, while moral foundations provide a powerful framework for understanding ideologies, they are not static. Societal shifts, generational changes, and global events can reshape what individuals prioritize. For example, younger generations often place greater emphasis on fairness and care, influencing the rise of progressive movements. To navigate this evolving landscape, stay attuned to cultural trends and be open to reevaluating one’s own moral priorities. This adaptability ensures that political engagement remains grounded in shared human values, even as ideologies transform.

Understanding Political Hacks: Tactics, Impact, and Modern Implications

You may want to see also

Justice and equality debates: Discussions on fairness, rights, and equitable distribution in political systems

Justice and equality debates often hinge on the tension between formal equality—treating everyone the same under the law—and substantive equality, which seeks to address systemic barriers to ensure genuine fairness. Consider the example of affirmative action policies. While critics argue they violate meritocracy by favoring certain groups, proponents contend that historical and structural disadvantages necessitate targeted interventions to level the playing field. This dichotomy underscores a fundamental question: Can true equality be achieved without acknowledging and rectifying past injustices?

To navigate this debate, policymakers must adopt a multi-step approach. First, identify the specific barriers—whether economic, social, or institutional—that hinder equal participation. Second, design interventions that are proportional and time-bound, ensuring they do not perpetuate new inequities. For instance, a 10-year program offering subsidized education for underrepresented communities could be paired with regular audits to assess its impact. Third, foster public dialogue to build consensus, as policies perceived as unfair can erode trust in the political system.

A cautionary note: Overemphasis on group-based rights can sometimes overshadow individual rights, creating unintended consequences. For example, blanket gender quotas in corporate boards may sideline qualified individuals in favor of less experienced candidates, undermining merit-based systems. Striking a balance requires nuanced policy design, such as implementing quotas only in sectors with proven bias and coupling them with transparency measures.

Ultimately, the goal of justice and equality debates is not to achieve perfection but to create systems that minimize harm and maximize opportunity. Practical tips for advocates include framing policies in terms of shared values like fairness and dignity, using data to highlight disparities, and proposing incremental changes that are easier to implement and evaluate. By focusing on both process and outcomes, societies can move closer to a political system that embodies moral principles of justice and equality.

Mastering Corporate Politics: Strategies to Thrive in Workplace Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Moral dilemmas in governance: Challenges leaders face when balancing competing ethical priorities in decision-making

Leaders in governance often confront moral dilemmas that pit one ethical principle against another, forcing them to weigh competing priorities without clear resolution. For instance, during a public health crisis, a leader might face the choice between enforcing strict lockdowns to save lives and preserving economic stability to prevent widespread poverty. This tension between utilitarianism (maximizing overall welfare) and deontological ethics (upholding individual rights) illustrates the inherent complexity of moral decision-making in governance. Such dilemmas are not merely theoretical; they demand practical solutions that inevitably leave some ethical considerations unfulfilled.

Consider the allocation of limited resources, a common challenge in governance. A leader must decide whether to invest in education to foster long-term societal development or in healthcare to address immediate suffering. This decision requires balancing the ethical imperative to provide for the vulnerable today against the moral obligation to secure a better future for the next generation. The absence of a universally accepted framework for prioritizing these values leaves leaders vulnerable to criticism regardless of their choice. This underscores the need for transparent decision-making processes that acknowledge the trade-offs involved.

To navigate these dilemmas, leaders can adopt a structured approach that begins with identifying the core ethical principles at stake. For example, in deciding whether to prioritize environmental conservation or economic growth, leaders must clarify the moral values underlying each option—sustainability versus prosperity. Next, they should engage stakeholders to understand the human impact of each choice, ensuring that decisions are not made in isolation. Finally, leaders must communicate their rationale openly, emphasizing the inevitability of compromise in moral dilemmas. This approach fosters accountability and builds public trust, even when outcomes are imperfect.

A cautionary note: leaders must resist the temptation to oversimplify moral dilemmas by framing them as binary choices. For instance, the debate over surveillance measures for national security often reduces to a false dichotomy between safety and privacy. In reality, nuanced solutions—such as targeted surveillance with robust oversight—can mitigate ethical concerns while achieving policy goals. Leaders who fail to explore such middle ground risk exacerbating societal divisions and eroding moral legitimacy.

In conclusion, moral dilemmas in governance are not obstacles to be avoided but inherent challenges to be managed. By embracing transparency, stakeholder engagement, and a willingness to acknowledge trade-offs, leaders can navigate these complexities with integrity. While no decision will satisfy all ethical priorities, a thoughtful and inclusive approach can ensure that governance remains rooted in moral principles, even in the face of uncertainty.

Political Oppression of Women: Barriers, Bias, and the Fight for Equality

You may want to see also

Culture’s influence on morality: How societal norms and cultural beliefs shape political morality and behavior

Moral politics is inherently shaped by the cultural and societal frameworks within which individuals and communities operate. These frameworks are not static; they evolve through historical, religious, and socio-economic influences, creating a mosaic of moral beliefs that guide political behavior. For instance, in collectivist cultures like Japan, the greater good often supersedes individual interests, influencing policies that prioritize social harmony over personal freedoms. Conversely, individualistic cultures like the United States emphasize personal rights and autonomy, leading to political agendas that champion individual liberties. Understanding these cultural underpinnings is crucial for deciphering why certain political actions are deemed moral in one society but not in another.

Consider the role of religion in shaping moral politics. In countries where religious institutions hold significant influence, such as Iran or the Vatican, political morality is often derived from sacred texts and theological doctrines. For example, Islamic republics frequently base their legal systems on Sharia law, which dictates moral and political conduct. In contrast, secular societies like Sweden derive their moral frameworks from humanist principles, emphasizing equality and social welfare. These divergent sources of moral authority highlight how cultural beliefs directly inform political decision-making, from legislation to foreign policy.

Cultural norms also dictate the boundaries of acceptable political behavior. In high-context cultures like South Korea, indirect communication and respect for hierarchy are deeply ingrained, influencing political discourse to be more nuanced and less confrontational. In low-context cultures like Germany, directness and transparency are valued, leading to more straightforward political debates. These norms extend to how politicians engage with the public, with some cultures tolerating charismatic leadership styles while others prefer humility and restraint. Such variations demonstrate how societal expectations mold not just the content of political morality but also its expression.

To navigate the complexities of cultural influence on moral politics, policymakers and citizens alike must adopt a comparative lens. For instance, when addressing global issues like climate change, understanding that some cultures prioritize intergenerational equity (e.g., Indigenous communities) while others focus on immediate economic gains (e.g., industrial nations) can foster more inclusive solutions. Practical steps include incorporating cultural sensitivity training in political education, encouraging cross-cultural dialogues, and designing policies that respect diverse moral frameworks. By acknowledging and integrating these cultural nuances, political morality can become a bridge rather than a barrier to global cooperation.

Ultimately, the interplay between culture and morality in politics is not a theoretical abstraction but a lived reality with tangible consequences. From shaping public opinion on issues like immigration and healthcare to influencing international relations, cultural beliefs act as the invisible hand guiding political behavior. Recognizing this dynamic allows for more informed, empathetic, and effective political engagement. It is not about homogenizing moral standards but about appreciating the richness of human diversity and leveraging it to build more just and equitable societies.

Understanding Dissensus Politics: Conflict, Pluralism, and Democratic Transformation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Moral politics refers to the intersection of ethics and political ideology, where political beliefs and policies are shaped by moral values and principles. It explores how individuals and groups use morality to justify their political positions.

Moral values influence political decisions by framing issues as right versus wrong, fair versus unfair, or just versus unjust. Politicians and voters often base their choices on moral convictions, such as equality, freedom, or responsibility.

No, moral politics vary across cultures and societies because moral values are shaped by historical, religious, and social contexts. What is considered morally right in one society may differ significantly in another.

Yes, moral politics can lead to polarization when opposing sides view their moral positions as absolute and incompatible with others. This can create deep divisions, as compromise becomes difficult when issues are framed in moral terms.