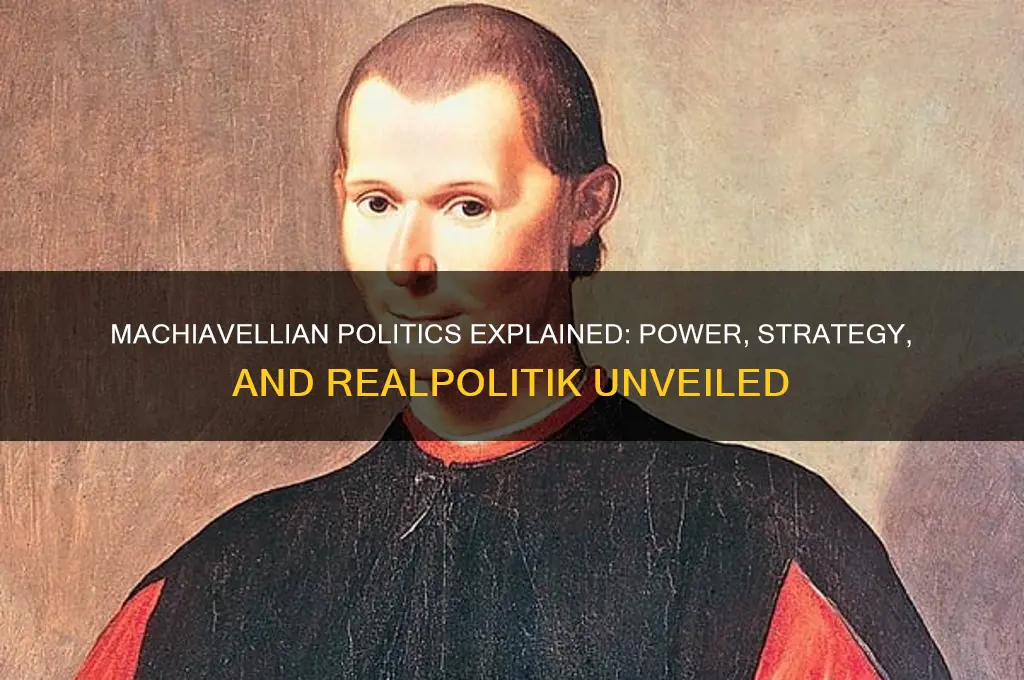

Machiavellian politics, rooted in the ideas of the 15th-century Italian philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli, particularly in his seminal work *The Prince*, refers to a pragmatic and often ruthless approach to political power. Machiavelli argued that effective leadership requires prioritizing stability and statecraft over moral principles, advocating for the use of cunning, deception, and even coercion to maintain control and achieve political goals. His philosophy challenges traditional ethical norms, emphasizing that rulers must be willing to act decisively, even if it means employing harsh or controversial methods, to secure and preserve their authority. Often misunderstood as advocating for tyranny, Machiavellian thought is more accurately characterized as a realist perspective on the complexities of governance, where the ends of security and order sometimes justify morally ambiguous means. This approach has profoundly influenced political theory and practice, sparking enduring debates about the balance between ethics and effectiveness in leadership.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Realpolitik | Politics based on practical and realistic considerations, often disregarding ethical or moral concerns. |

| Power as the Ultimate Goal | The primary objective is to acquire, maintain, and expand power at all costs. |

| Manipulation and Deception | Use of cunning, deceit, and strategic manipulation to achieve political ends. |

| Pragmatism Over Idealism | Prioritizing what works over what is morally or ethically right. |

| Centralization of Authority | Concentration of power in a strong leader or state to ensure control. |

| Fear as a Tool | Leveraging fear to maintain order and loyalty among subjects or followers. |

| Adaptability | Willingness to change tactics and strategies based on circumstances. |

| Skepticism of Human Nature | Viewing humans as inherently self-interested and untrustworthy. |

| Short-Term Gains Over Long-Term Goals | Focusing on immediate results rather than long-term consequences. |

| Use of Force When Necessary | Employing coercion or violence when diplomacy fails to achieve objectives. |

| Appearance vs. Reality | Maintaining a public image that may differ from true intentions or actions. |

| Survival of the State/Leader | Ensuring the survival and stability of the state or leader above all else. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- The Prince's Core Principles: Power, statecraft, and the ends justify the means in leadership

- Realism vs. Morality: Prioritizing practical outcomes over ethical considerations in political decisions

- Manipulation and Control: Using deception, fear, and strategy to maintain authority and dominance

- State Survival: Ensuring the state's longevity, even at the expense of individual rights

- Machiavelli's Legacy: Influence on modern politics, authoritarianism, and pragmatic governance strategies

The Prince's Core Principles: Power, statecraft, and the ends justify the means in leadership

Niccolò Machiavelli's *The Prince* is a seminal work that distills the essence of leadership into a set of core principles centered on power, statecraft, and the idea that the ends justify the means. At its heart, Machiavelli argues that a ruler's primary goal is to maintain and expand power, even if it requires actions that might be deemed morally questionable. This pragmatic approach to leadership is both controversial and instructive, offering timeless lessons for those who seek to govern effectively.

Step 1: Prioritize Power Above All Else

Machiavelli asserts that a prince's survival and success depend on consolidating power. This involves understanding the nature of human behavior and using it to one's advantage. For instance, he advises rulers to be both feared and loved but notes that, if forced to choose, it is safer to be feared. Fear, when managed correctly, ensures loyalty and deters rebellion. Practical application: Leaders must assess their environments, identify potential threats, and act decisively to neutralize them. This might include strategic alliances, calculated displays of strength, or even the elimination of rivals.

Caution: The Fine Line Between Fear and Hatred

While fear is a tool, Machiavelli warns against its misuse. A ruler who becomes tyrannical risks inciting hatred, which can lead to instability and overthrow. The key is to inspire fear without becoming oppressive. For example, punishments should be swift and justified, not arbitrary. Modern leaders can apply this by balancing authority with fairness, ensuring that their actions are perceived as necessary rather than cruel.

Step 2: Master the Art of Statecraft

Statecraft, or the skill of governing, is central to Machiavelli's philosophy. It involves adaptability, foresight, and the ability to navigate complex political landscapes. A prince must be willing to shift strategies based on circumstances, appearing virtuous when it serves their interests but ready to act ruthlessly when required. Practical tip: Leaders should cultivate a deep understanding of their domains, including the motivations of their subjects and the dynamics of power. This might involve gathering intelligence, fostering a network of informants, or studying historical precedents.

Comparative Analysis: Virtue vs. Effectiveness

Machiavelli challenges traditional notions of virtue, arguing that a ruler's effectiveness is more important than moral purity. For instance, while honesty is admirable, deception can be a necessary tool in diplomacy. Compare this to modern corporate leadership, where transparency is often valued but strategic ambiguity is sometimes employed to gain a competitive edge. The takeaway: Leaders must be willing to prioritize results over rigid adherence to ethical norms, provided their actions serve the greater good of the state.

Machiavelli's most controversial principle is that the success of a ruler's actions is the ultimate measure of their morality. This does not advocate for indiscriminate cruelty but emphasizes that difficult decisions are often necessary to achieve stability and prosperity. For example, a leader might need to make unpopular cuts to public spending to prevent economic collapse. The key is to act with purpose and ensure that the long-term benefits outweigh the short-term costs. Practical advice: Leaders should weigh their decisions carefully, considering both immediate consequences and future implications, and be prepared to defend their choices as necessary for the greater good.

In applying Machiavelli's principles, leaders must balance pragmatism with prudence, ensuring that their pursuit of power and stability does not devolve into tyranny. The core lesson is clear: effective leadership requires a willingness to make tough choices, master the complexities of governance, and always keep the end goal in sight.

Identity Politics: Divisive Tool or Necessary Voice for Marginalized Groups?

You may want to see also

Realism vs. Morality: Prioritizing practical outcomes over ethical considerations in political decisions

Machiavellian politics, rooted in Niccolò Machiavelli's *The Prince*, advocates for prioritizing practical outcomes over ethical considerations in political decision-making. This philosophy challenges the notion that morality should guide leadership, instead emphasizing the pursuit of power, stability, and effectiveness. In this framework, leaders must often make difficult choices that, while morally ambiguous, ensure the survival and prosperity of the state. The tension between realism and morality is not merely theoretical; it is a recurring dilemma in governance, where idealism can collide with the harsh realities of power.

Consider the decision to engage in preemptive military action. From a moral standpoint, such actions may violate principles of justice and human rights, particularly if they result in civilian casualties. However, a realist perspective argues that preemptive strikes can prevent greater future harm by neutralizing immediate threats. For instance, the 2003 invasion of Iraq was justified by some as a necessary measure to eliminate weapons of mass destruction, despite widespread ethical concerns. This example illustrates how Machiavellian realism can justify actions that prioritize state security over moral purity, even when those actions are controversial or condemned by international norms.

To navigate this tension, leaders must adopt a pragmatic approach that balances ethical ideals with practical necessities. This does not mean abandoning morality altogether but rather recognizing that absolute moral adherence can sometimes lead to unintended consequences. For example, refusing to negotiate with authoritarian regimes on principle may prolong suffering for populations in need of aid. Instead, engaging with such regimes—albeit cautiously—can yield practical benefits, such as humanitarian access or diplomatic leverage. The key is to assess each situation on its merits, weighing the moral costs against the potential gains.

Critics argue that prioritizing realism over morality risks normalizing unethical behavior and eroding the moral foundation of society. However, Machiavelli’s framework does not advocate for unchecked immorality but rather for strategic flexibility. Leaders must remain accountable, ensuring that their actions, while pragmatic, do not cross into gratuitous harm or corruption. Transparency and public discourse can serve as checks, allowing citizens to evaluate whether a decision’s practical benefits justify its moral compromises. For instance, public debates over drone strikes highlight how societies can scrutinize the ethical trade-offs of realist policies.

In practice, embracing Machiavellian realism requires leaders to cultivate emotional detachment and long-term vision. They must be willing to make unpopular decisions, such as cutting social programs to stabilize an economy or forming alliances with unsavory actors to achieve strategic goals. This approach demands a clear understanding of priorities: is the primary goal to uphold abstract moral principles, or to achieve tangible outcomes like security, prosperity, and stability? By framing decisions in this light, leaders can act decisively without being paralyzed by ethical dilemmas. Ultimately, the art of Machiavellian politics lies in mastering the delicate balance between realism and morality, ensuring that the pursuit of practical outcomes does not come at the expense of humanity’s core values.

Washington's Political Opponents: Unveiling the Hidden Resistance in Early America

You may want to see also

Manipulation and Control: Using deception, fear, and strategy to maintain authority and dominance

Machiavellian politics, rooted in the philosophies of Niccolò Machiavelli, often revolves around the pragmatic use of power, where morality is secondary to maintaining control. At its core, manipulation and control are wielded as essential tools, employing deception, fear, and strategic planning to ensure dominance. This approach is not about fairness or ethics but about effectiveness—a cold calculus of power dynamics. Leaders who adopt this mindset understand that authority is fragile and must be actively defended, often through methods that may seem ruthless but are deemed necessary for survival.

Consider the strategic use of deception, a cornerstone of Machiavellian manipulation. It involves creating illusions to mislead opponents or the public, such as feigning weakness to lure adversaries into complacency or exaggerating strength to deter challenges. For instance, a leader might publicly endorse a policy while secretly undermining it, ensuring their true objectives remain hidden. This tactic requires precision; overused, deception erodes trust, but when applied judiciously, it can neutralize threats before they materialize. The key is to maintain plausible deniability, ensuring that the manipulator’s hands remain clean while their goals are achieved.

Fear, another potent instrument, is not merely about instilling terror but about calibrating it to control behavior. Machiavelli argued that it is better to be feared than loved if one cannot be both, as fear is a more reliable motivator. This does not mean constant brutality; instead, it involves calculated displays of power, such as punishing dissenters publicly to set an example. For example, a leader might target a high-profile critic to send a message to others, ensuring compliance through the fear of repercussions. However, fear must be balanced with occasional rewards to prevent rebellion, a delicate equilibrium that requires constant vigilance and adaptability.

Strategic planning ties these elements together, providing a framework for long-term dominance. It involves anticipating threats, positioning allies, and creating dependencies that ensure loyalty. A Machiavellian leader might cultivate a network of informants, distribute resources selectively, or manipulate conflicts to weaken rivals. For instance, by pitting factions against each other, a leader can remain above the fray while diminishing potential challengers. This approach demands foresight and a willingness to act decisively, even if it means sacrificing short-term stability for long-term control.

In practice, mastering manipulation and control requires a deep understanding of human nature and situational awareness. It is not a one-size-fits-all approach but a tailored strategy that adapts to circumstances. For those seeking to implement such tactics, start by identifying vulnerabilities—both your own and those of others. Use deception sparingly but effectively, and deploy fear as a scalpel, not a hammer. Finally, always think several moves ahead, ensuring that every action contributes to the broader goal of maintaining authority. While this approach may seem cynical, its effectiveness in securing power is undeniable, making it a timeless guide for those who prioritize dominance above all else.

Understanding Political Dealignment: Causes, Effects, and Modern Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

State Survival: Ensuring the state's longevity, even at the expense of individual rights

Machiavellian politics, rooted in Niccolò Machiavelli’s *The Prince*, prioritizes the survival and strength of the state above all else, often justifying actions that may seem ruthless or morally ambiguous. In this framework, individual rights are secondary to the state’s longevity, a principle that has been both criticized and emulated throughout history. Ensuring state survival at the expense of individual liberties requires a calculated approach, balancing power, control, and strategic decision-making.

Step 1: Centralize Power to Eliminate Threats

To secure the state’s survival, Machiavelli advocates for the centralization of power in the hands of a strong leader. This involves dismantling or co-opting institutions that could challenge authority, such as independent media, opposition groups, or regional power centers. For example, historical regimes like the Soviet Union under Stalin or modern authoritarian states like North Korea have employed this tactic, suppressing dissent to maintain control. Practical implementation includes surveillance systems, propaganda campaigns, and legal frameworks that criminalize opposition. Caution: Over-centralization can lead to internal stagnation and external isolation, so maintain a facade of legitimacy through controlled institutions.

Step 2: Prioritize Collective Stability Over Individual Freedom

Machiavellian logic dictates that the state’s stability is paramount, even if it means curtailing personal freedoms. This often manifests in policies that restrict speech, assembly, or movement under the guise of national security or public order. China’s social credit system is a contemporary example, where individual behavior is monitored and regulated to ensure compliance with state goals. To implement this effectively, frame restrictions as necessary for the greater good, using crises (real or manufactured) to justify harsh measures. However, be mindful of public perception; excessive oppression can breed resentment and resistance.

Step 3: Use Fear and Reward Strategically

Machiavelli famously debated whether it is better to be feared or loved, concluding that a ruler should aim for both but prioritize fear if forced to choose. In the context of state survival, this translates to a dual strategy of punishment for non-compliance and rewards for loyalty. For instance, tax breaks or public recognition can incentivize alignment with state goals, while harsh penalties deter dissent. Historical examples include the Roman Empire’s use of public executions to instill fear and the modern U.S. Patriot Act’s expansion of surveillance post-9/11. Balance is key: too much fear alienates the populace, while too much leniency risks disorder.

Analysis: The Trade-Offs and Long-Term Implications

While prioritizing state survival over individual rights can provide short-term stability, it carries significant risks. Suppressed populations may eventually revolt, and the lack of innovation and dissent can hinder progress. For instance, East Germany’s strict control under the Stasi led to widespread discontent and ultimately collapse. To mitigate this, periodically assess the state’s legitimacy and adapt strategies to maintain public support without compromising control. Long-term survival requires not just force but also the appearance of fairness and the ability to evolve with societal demands.

Takeaway: A Delicate Balance of Power and Pragmatism

Machiavellian state survival is a high-stakes game of pragmatism, where moral considerations are secondary to results. By centralizing power, prioritizing stability, and using fear and rewards strategically, a state can ensure its longevity. However, success depends on careful calibration and an understanding of both internal and external dynamics. As Machiavelli himself warned, the ruler must be willing to adapt, for rigidity in the face of change is the greatest threat to survival.

Is 'No Problem' Polite? Decoding Modern Etiquette in Responses

You may want to see also

Machiavelli's Legacy: Influence on modern politics, authoritarianism, and pragmatic governance strategies

Niccolò Machiavelli's *The Prince*, written in the early 16th century, remains a cornerstone for understanding the interplay between power, morality, and governance. His legacy is not confined to history; it permeates modern politics, where leaders often grapple with the tension between ethical ideals and pragmatic realities. Machiavelli's assertion that a ruler must be willing to act immorally to maintain stability has become a blueprint for both authoritarian regimes and democratic leaders facing crises. This duality—the embrace of ruthlessness for the sake of order—defines his enduring influence.

Consider the rise of authoritarianism in the 21st century. Leaders like Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping exemplify Machiavellian principles in action. Putin's annexation of Crimea and Xi's consolidation of power through anti-corruption campaigns and surveillance systems reflect Machiavelli's advice to prioritize control over consensus. These leaders justify their actions as necessary for national unity and security, echoing Machiavelli's argument that the ends justify the means. Critics argue this approach undermines democracy, but proponents see it as effective governance in turbulent times. The takeaway? Machiavelli's ideas offer a toolkit for authoritarian rule, but their application comes at the cost of individual freedoms.

Pragmatic governance strategies in democratic systems also bear Machiavelli's imprint. During crises, leaders often adopt a results-oriented approach that mirrors his philosophy. For instance, Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the wartime measures of Winston Churchill demonstrate how democratic leaders can employ Machiavellian tactics—centralizing power, bypassing traditional checks, and making tough decisions—to address existential threats. The key difference lies in the temporary nature of these measures, unlike authoritarian regimes where such tactics become permanent. This highlights Machiavelli's relevance in both democratic and autocratic contexts, though the ethical boundaries remain fiercely contested.

To implement Machiavellian strategies ethically, leaders must balance pragmatism with accountability. A practical tip: establish clear limits on emergency powers and ensure transparency in decision-making. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, countries like New Zealand and South Korea adopted strict measures but maintained public trust through consistent communication and temporary mandates. This approach aligns with Machiavelli's emphasis on adaptability while avoiding the pitfalls of unchecked authority. The challenge is to use his principles as a guide, not a mandate, ensuring governance remains responsive to the needs of the people.

In conclusion, Machiavelli's legacy is a double-edged sword. His ideas provide a framework for effective governance in times of crisis but also enable authoritarian overreach. Modern leaders must navigate this tension, borrowing from his pragmatic strategies while safeguarding democratic values. The question remains: can Machiavelli's principles be wielded responsibly, or do they inherently corrupt the systems they seek to stabilize? The answer lies in how leaders choose to interpret and apply his timeless, yet contentious, wisdom.

Mastering Political Skill: Navigating Influence and Power in Organizations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Machiavellian politics refers to the political philosophy and strategies derived from the writings of Niccolò Machiavelli, particularly his book *The Prince*. It emphasizes pragmatism, realism, and the use of power to achieve and maintain political control, often prioritizing results over moral considerations.

The core principles include the pursuit of power at all costs, the use of deception and manipulation when necessary, the importance of strength and fear over love, and the belief that political leaders must be willing to act immorally to secure stability and success.

Machiavellian politics is often criticized as unethical because it prioritizes outcomes over moral principles. However, proponents argue that it reflects the harsh realities of political leadership and that morality must sometimes be set aside to achieve greater stability or security.

Traditional ethics in leadership emphasizes virtues like honesty, justice, and compassion, whereas Machiavellian politics focuses on effectiveness, survival, and the maintenance of power. Machiavelli believed leaders should be willing to act unethically if it ensures their authority and the state's stability.

Yes, modern examples include leaders who prioritize political survival over moral principles, use strategic deception, or employ fear to control populations. Figures like Vladimir Putin and certain authoritarian rulers are often cited as embodying Machiavellian tactics in contemporary politics.

![The Art of Worldly Wisdom, Book One: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Strategies for Success [Mystic Eye, Economy Ed.]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71wXav7JK+L._AC_UY218_.jpg)