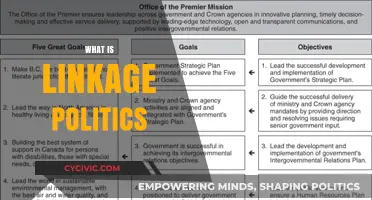

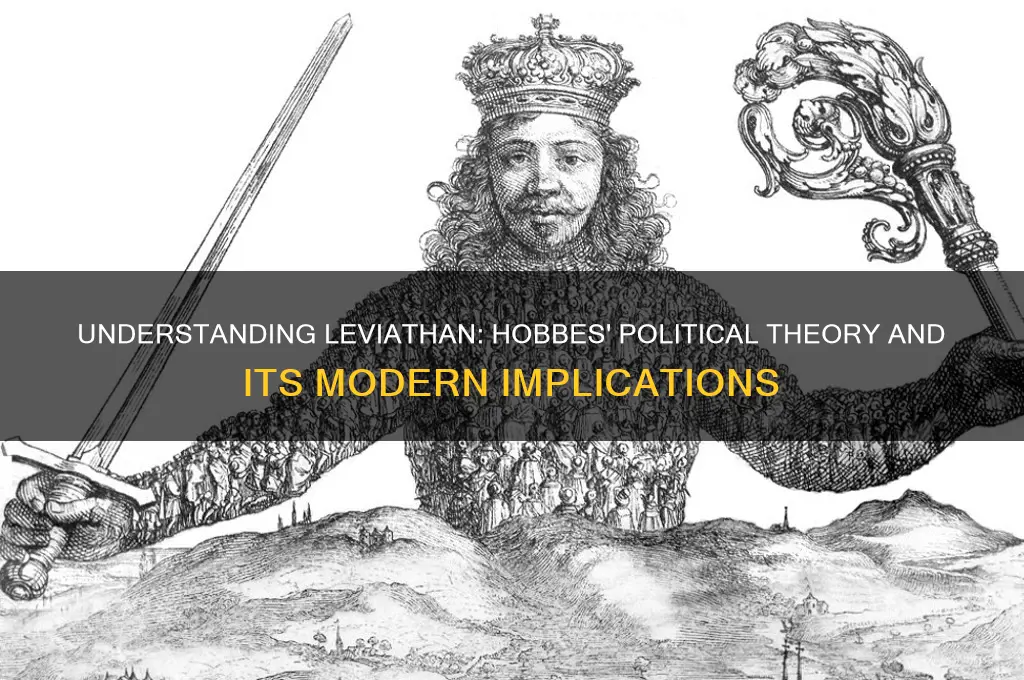

The concept of the Leviathan in politics originates from Thomas Hobbes' seminal work, *Leviathan* (1651), where it symbolizes the centralized authority of a sovereign state created to escape the chaos of the state of nature. Hobbes argued that individuals, driven by self-interest and fear, voluntarily surrender their freedoms to a powerful governing entity—the Leviathan—in exchange for security and social order. This political construct represents absolute sovereignty, emphasizing the necessity of a strong, undivided authority to prevent conflict and ensure stability. The Leviathan’s role is to enforce laws, maintain peace, and protect its citizens, even at the cost of individual liberties, making it a cornerstone of modern political philosophy and a subject of ongoing debate about the balance between authority and freedom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A powerful, centralized state authority, often depicted as a monstrous entity. |

| Origin | Coined by Thomas Hobbes in his 1651 work Leviathan. |

| Core Purpose | To establish social order and prevent the "state of nature" (chaos). |

| Sovereignty | Absolute and indivisible power vested in a single authority (monarch or state). |

| Social Contract | Individuals surrender freedoms to the Leviathan in exchange for security. |

| Human Nature | Assumes humans are self-interested and require a strong authority to coexist peacefully. |

| Fear as Motivation | The Leviathan's power is maintained through fear of punishment. |

| Centralization | All power is concentrated in a single entity, eliminating competing authorities. |

| Legitimacy | Derived from its ability to maintain order, not from divine right or consent. |

| Modern Relevance | Often used to describe authoritarian or highly centralized governments. |

| Criticism | Accused of justifying tyranny and suppressing individual liberties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hobbes' Social Contract Theory: Leviathan as the commonwealth, ensuring peace via absolute sovereignty

- Absolute Sovereignty: Central authority to prevent chaos, as per Hobbes' philosophy

- Human Nature in Leviathan: Self-interest and fear drive the need for a strong state

- Critiques of Leviathan: Concerns over tyranny, individual rights, and power concentration

- Modern Relevance: Leviathan's principles in contemporary governance and authoritarian regimes

Hobbes' Social Contract Theory: Leviathan as the commonwealth, ensuring peace via absolute sovereignty

In Thomas Hobbes' seminal work, *Leviathan*, the titular concept represents the commonwealth—a sovereign entity formed through a social contract to escape the "war of all against all" in the state of nature. This political construct is not merely a symbolic figure but a practical solution to humanity's inherent self-interest and the chaos it breeds. Hobbes argues that individuals, driven by fear of violent death and the desire for self-preservation, voluntarily surrender their natural freedoms to an absolute authority. This authority, the Leviathan, holds supreme power to enforce laws and maintain order, ensuring peace and security for its subjects.

The Leviathan’s absolute sovereignty is the linchpin of Hobbes’ theory. Unlike modern democratic ideals, which often emphasize checks and balances, Hobbes advocates for undivided power. He posits that any division of authority would lead to conflict and undermine the very purpose of the commonwealth. For instance, if multiple entities held power, they would inevitably compete, reverting society to the state of nature. Thus, the Leviathan’s unchallenged rule is not a tyranny but a necessity for stability. This perspective challenges contemporary notions of governance, urging readers to consider the trade-offs between liberty and security.

To understand the Leviathan’s role, consider a practical analogy: a ship navigating treacherous waters. The crew (citizens) agrees to follow the captain’s (sovereign’s) commands without question to ensure safe passage. Disobedience or mutiny would jeopardize everyone aboard. Similarly, the Leviathan’s authority is absolute because partial obedience would render the social contract ineffective. Hobbes’ theory is particularly relevant in post-conflict societies, where centralized authority is often essential to rebuild trust and prevent relapse into chaos. For example, nations emerging from civil wars frequently adopt strong central governments to restore order, echoing Hobbesian principles.

Critics argue that absolute sovereignty risks despotism, but Hobbes counters that the Leviathan’s legitimacy derives from the consent of the governed. Individuals agree to obey not out of coercion but as a rational choice to avoid the horrors of the state of nature. This distinction is crucial: the Leviathan is not a ruler above the law but the embodiment of the collective will. However, this raises questions about accountability. Hobbes addresses this by asserting that the sovereign’s primary duty is to ensure peace, and subjects are obligated to obey only as long as the sovereign fulfills this role. If the Leviathan fails to protect its citizens, the social contract is void, though Hobbes cautions against rebellion, as it would plunge society back into chaos.

In applying Hobbes’ theory today, policymakers must balance the need for strong governance with safeguards against abuse of power. For instance, in crisis management—such as pandemics or economic collapses—temporary centralization of authority can be effective, but mechanisms like term limits or independent judiciary can prevent overreach. Hobbes’ Leviathan remains a provocative framework, reminding us that peace often requires sacrifice, and the form of that sacrifice—absolute sovereignty—is both a solution and a challenge.

Understanding the English Political Revolution: Causes, Events, and Legacy

You may want to see also

Absolute Sovereignty: Central authority to prevent chaos, as per Hobbes' philosophy

In the realm of political philosophy, Thomas Hobbes' concept of the Leviathan stands as a towering argument for absolute sovereignty. Imagine a society without a central authority, where every individual acts solely in self-interest. Hobbes paints a grim picture of such a "state of nature," characterized by constant fear, violence, and instability. To escape this chaos, he proposes a social contract: individuals surrender their natural freedoms to a single, all-powerful sovereign in exchange for security and order. This sovereign, the Leviathan, becomes the embodiment of absolute authority, holding the power to make and enforce laws, ensuring peace and preventing the descent back into anarchy.

Hobbes' argument is not merely theoretical. He lived through the English Civil War, a period of immense turmoil and bloodshed. Witnessing the breakdown of societal order firsthand, he saw absolute sovereignty as the only antidote to the fragility of human nature. The Leviathan, he believed, was the necessary glue to hold society together, preventing the "war of all against all" that would otherwise ensue.

However, absolute sovereignty is a double-edged sword. While it promises stability, it also carries the risk of tyranny. A sovereign with unchecked power can easily become oppressive, trampling on individual rights and freedoms. Hobbes acknowledges this danger but argues that the alternative – the chaos of the state of nature – is far worse. He believes that individuals, rationally fearing the horrors of anarchy, will submit to even a tyrannical sovereign rather than risk the alternative.

This raises a crucial question: how can we ensure the Leviathan serves its intended purpose without becoming a monster itself? Hobbes offers no easy answers. He emphasizes the importance of a strong, centralized authority but provides little guidance on how to prevent its abuse. This tension between order and liberty remains a central challenge in political philosophy, a legacy of Hobbes' Leviathan that continues to provoke debate and shape our understanding of the role of government.

Are Political Articles Factual? Examining Bias and Accuracy in Media

You may want to see also

Human Nature in Leviathan: Self-interest and fear drive the need for a strong state

Thomas Hobbes' *Leviathan* posits that human nature is fundamentally driven by self-interest and fear, creating a state of perpetual conflict in the absence of a strong central authority. Imagine a society where individuals act solely to maximize their own gain, unbound by moral or legal constraints. In this "state of nature," as Hobbes calls it, life would be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." Fear of death and the desire for self-preservation become the primary motivators, leading to a war of all against all. This bleak vision highlights the necessity of a powerful state, a "Leviathan," to impose order and ensure survival.

Consider the example of resource scarcity. In a Hobbesian framework, limited resources like food, water, or land would immediately become flashpoints for conflict. Self-interested individuals, driven by fear of deprivation, would compete ruthlessly, leading to chaos. A strong state, however, can establish rules for resource distribution, enforce property rights, and mediate disputes, thereby preventing societal collapse. This is not merely theoretical; historical examples abound, from the collapse of civilizations due to resource wars to the stability brought by centralized governments in modern nation-states.

The persuasive argument here is clear: without a Leviathan, human self-interest and fear would render cooperation impossible. Hobbes argues that individuals must surrender some of their freedoms to a sovereign authority in exchange for security. This social contract is not a matter of altruism but of rational self-preservation. By submitting to a common power, individuals escape the constant threat of violence and create the conditions for prosperity. Critics might argue that such a state risks tyranny, but Hobbes counters that the alternative—anarchy—is far worse.

To apply this concept practically, consider modern governance. Strong states invest in institutions like law enforcement, judiciary systems, and social safety nets to mitigate the effects of self-interest and fear. For instance, progressive taxation and welfare programs address economic inequality, reducing the fear of destitution that might otherwise drive individuals to desperate measures. Similarly, international organizations like the United Nations attempt to extend the Leviathan’s reach beyond national borders, fostering cooperation and preventing global conflicts.

In conclusion, Hobbes’ *Leviathan* offers a stark but compelling analysis of human nature and its implications for political order. By recognizing that self-interest and fear are inherent to humanity, we understand why a strong state is not just desirable but necessary. While the balance between authority and liberty remains a perennial challenge, the alternative—a world without the Leviathan—is a reminder of the fragility of civilization itself.

Shaping the Nation: The Impact of Political Socialization on America

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Critiques of Leviathan: Concerns over tyranny, individual rights, and power concentration

The concept of Leviathan, as articulated by Thomas Hobbes, presents a centralized authority as the solution to the chaos of the state of nature. Yet, this very solution has sparked enduring critiques centered on tyranny, the erosion of individual rights, and the dangers of power concentration. These concerns are not merely theoretical; they manifest in historical and contemporary political systems, serving as cautionary tales for those who wield or acquiesce to unchecked authority.

Consider the mechanism of power concentration within a Leviathan state. By design, such a system consolidates decision-making in a single entity, often justified as necessary for stability and order. However, this concentration inherently limits the distribution of power among citizens, creating a fertile ground for abuse. For instance, the 20th century saw regimes like Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union exploit centralized authority to suppress dissent, eliminate political opponents, and commit atrocities. These examples illustrate how Leviathan’s promise of security can devolve into tyranny when power is not balanced by accountability or dispersed institutions.

Critics also argue that Leviathan’s emphasis on collective order undermines individual rights. Hobbes’s social contract demands that individuals surrender their natural freedoms in exchange for protection, but this trade-off often tilts toward excessive control. In practice, governments may justify encroaching on personal liberties—such as freedom of speech, assembly, or privacy—in the name of maintaining order. Modern surveillance states, where citizens are monitored under the guise of national security, exemplify this tension. The question arises: At what point does the Leviathan’s protection become a shackle, stifling the very autonomy it claims to safeguard?

A comparative analysis reveals that decentralized systems, such as federalism or constitutional democracies, offer safeguards against Leviathan’s pitfalls. By dividing power among multiple levels of government or branches, these systems create checks and balances that mitigate the risk of tyranny. For example, the U.S. Constitution’s separation of powers and Bill of Rights were explicitly designed to prevent the concentration of authority and protect individual liberties. This structural approach underscores the importance of institutional design in countering Leviathan’s inherent risks.

To navigate these critiques, practical steps can be taken to temper Leviathan’s excesses. First, establish robust legal frameworks that enshrine individual rights and limit governmental overreach. Second, foster a culture of civic engagement, where citizens actively hold their leaders accountable. Third, invest in independent institutions—such as a free press, judiciary, and civil society—that act as watchdogs against power concentration. These measures, while not foolproof, provide a bulwark against the descent into tyranny and ensure that the Leviathan serves its people rather than dominating them.

In conclusion, the critiques of Leviathan highlight the delicate balance between order and liberty. While centralized authority may offer stability, it demands vigilant scrutiny to prevent its darker manifestations. By learning from history and adopting structural safeguards, societies can harness Leviathan’s strengths without succumbing to its dangers.

Art of Constructive Criticism: Mastering Polite Yet Effective Communication

You may want to see also

Modern Relevance: Leviathan's principles in contemporary governance and authoritarian regimes

The concept of the Leviathan, as articulated by Thomas Hobbes in the 17th century, posits a centralized, all-powerful state as the solution to the chaos of the "state of nature." In contemporary governance, this principle manifests in various forms, particularly within authoritarian regimes that prioritize order and control above individual liberties. These modern Leviathans often employ advanced technologies, such as surveillance systems and data analytics, to monitor and regulate citizen behavior, ensuring compliance with state directives. For instance, China’s Social Credit System exemplifies this approach, blending traditional authoritarian tactics with cutting-edge technology to enforce social and political conformity.

To understand the modern relevance of Leviathan’s principles, consider the following steps: first, identify regimes that exhibit centralized authority and limited political pluralism. Second, analyze their use of technology to extend state control. Third, evaluate the trade-offs between stability and individual freedoms. Authoritarian governments like Russia and North Korea demonstrate how Leviathan’s ideas are adapted to modern contexts, using propaganda, censorship, and coercion to maintain power. These regimes often justify their actions as necessary for national security or cultural preservation, echoing Hobbes’s argument that absolute sovereignty prevents societal collapse.

A comparative analysis reveals that while democratic systems distribute power and protect civil liberties, authoritarian Leviathans concentrate authority to impose uniformity. For example, Hungary under Viktor Orbán has systematically weakened democratic institutions, consolidating power through legal reforms and media control. This contrasts with liberal democracies, which balance state authority with checks and balances. However, even in democracies, emergencies like pandemics have led to temporary expansions of state power, raising questions about the enduring appeal of Leviathan’s principles in times of crisis.

Persuasively, it can be argued that the rise of modern Leviathans reflects a global trend toward securitization, where states prioritize control over openness. This is evident in the proliferation of surveillance capitalism, where private corporations and governments collaborate to monitor populations. Critics warn that such practices erode privacy and dissent, creating societies where conformity is enforced rather than chosen. Yet, proponents contend that strong central authority is essential for addressing complex challenges like climate change or global health crises, which require coordinated, decisive action.

In conclusion, Leviathan’s principles remain deeply relevant in contemporary governance, particularly within authoritarian regimes that leverage technology to enforce control. While these systems promise stability, they often come at the cost of individual freedoms and democratic norms. As the world grapples with increasing uncertainty, the tension between order and liberty will continue to shape political systems, making Hobbes’s Leviathan a timeless yet contentious framework for understanding modern governance. Practical tips for citizens include staying informed about state policies, advocating for transparency, and supporting institutions that safeguard democratic values.

Polite Gestures: The Art of Offering a Seat with Grace and Respect

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Leviathan is a concept introduced by Thomas Hobbes in his 1651 book *Leviathan*, representing a powerful centralized authority or state created through a social contract to maintain order and prevent chaos in society.

Hobbes used "Leviathan" to symbolize the immense power and authority of the state, likening it to the biblical sea monster Leviathan, which represents overwhelming strength and sovereignty.

In Hobbes' view, the Leviathan's role is to enforce laws, protect citizens, and ensure peace by holding absolute power, as individuals surrender their natural rights to it in exchange for security.

The concept of Leviathan remains relevant in discussions about state authority, the social contract, and the balance between individual freedoms and government power in modern political systems.