Legitimacy in politics refers to the perception that a government, its institutions, and its actions are rightful, just, and deserving of public acceptance and obedience. It is a cornerstone of political stability, as it ensures that authority is exercised with the consent of the governed rather than through coercion alone. Legitimacy can stem from various sources, such as democratic elections, adherence to constitutional principles, cultural traditions, or the ability to deliver public goods and maintain order. When a political system lacks legitimacy, it risks erosion of trust, social unrest, and challenges to its authority. Understanding the concept of legitimation—the processes and mechanisms through which political power gains legitimacy—is crucial for analyzing the durability and effectiveness of governments in diverse political contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The process by which authority, power, or governance is justified and accepted as rightful by the governed. |

| Key Sources | Tradition, Charisma, Legal-Rationality (Max Weber's tripartite classification). |

| Mechanisms | Elections, Referendums, Public Opinion, Media, Education, Symbolic Representation. |

| Types | Input Legitimacy (procedural fairness), Output Legitimacy (effectiveness of governance), Normative Legitimacy (alignment with societal values). |

| Importance | Ensures stability, reduces conflict, fosters trust in institutions, and promotes compliance with laws. |

| Challenges | Corruption, Inequality, Lack of Transparency, Erosion of Trust, Political Polarization. |

| Contemporary Issues | Populism, Disinformation, Digital Democracy, Global Governance Legitimacy. |

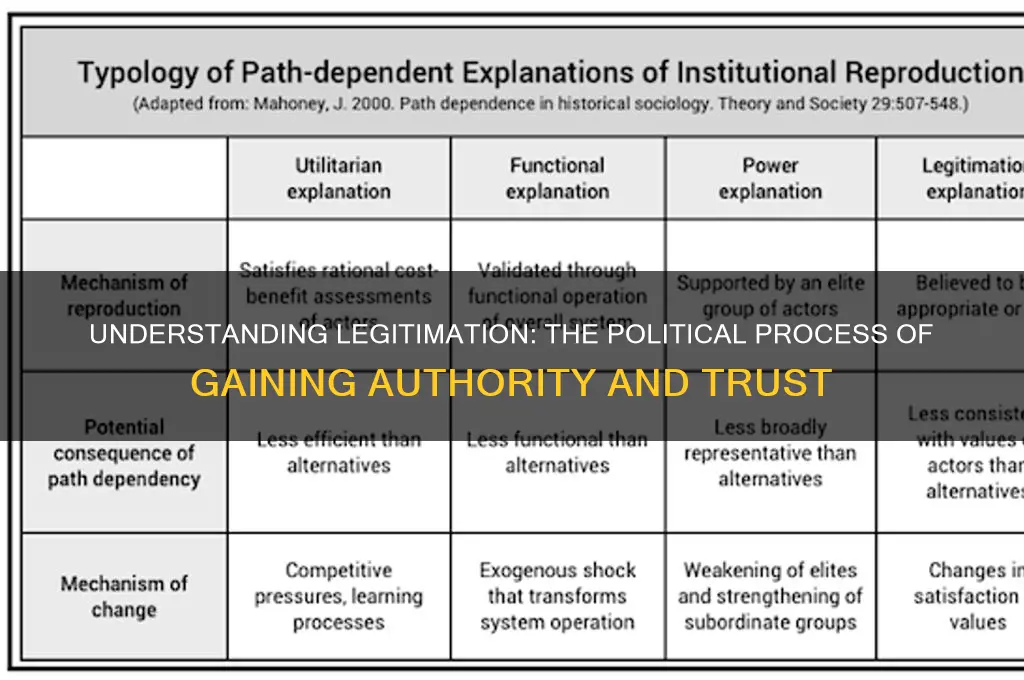

| Theoretical Perspectives | Democratic Theory, Social Contract Theory, Critical Theory, Neo-Institutionalism. |

| Measurement | Public Opinion Polls, Voter Turnout, Compliance Rates, Trust Indices, Protest Frequency. |

| Examples | Constitutional Governments, Monarchies, Revolutionary Regimes, International Organizations (e.g., UN, EU). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Legal Basis: Understanding the legal framework that grants legitimacy to political systems and leaders

- Popular Consent: Role of public approval and elections in legitimizing political authority

- Historical Legitimacy: How historical narratives and traditions validate political power and governance

- Institutional Trust: Importance of credible institutions in maintaining political legitimacy and stability

- Performance Legitimacy: How effective governance and policy outcomes reinforce political legitimacy over time

Legal Basis: Understanding the legal framework that grants legitimacy to political systems and leaders

The legal basis of political legitimacy is rooted in the formal structures and rules that define a government's authority. Constitutions, statutes, and international treaties serve as the cornerstone of this framework, providing a clear blueprint for how power is acquired, exercised, and transferred. For instance, the U.S. Constitution outlines the separation of powers, checks and balances, and the process of electing leaders, thereby legitimizing the federal government's authority. Similarly, the European Union's Treaty on European Union establishes the legal foundation for its supranational governance, granting legitimacy to its institutions and decision-making processes. Without such a legal framework, political systems risk descending into arbitrariness, where power is wielded without clear justification or accountability.

Understanding the legal basis of legitimacy requires examining how laws are created, interpreted, and enforced. In democratic systems, legitimacy often hinges on the principle of popular sovereignty, where laws are enacted through representative institutions like parliaments or congresses. For example, in Germany, the Basic Law mandates that all legislation must be passed by the Bundestag, ensuring that governance reflects the will of the people. However, the legal framework must also include mechanisms for judicial review, as seen in India’s Supreme Court, which upholds the Constitution and strikes down laws that violate fundamental rights. This dual emphasis on legislative representation and judicial oversight ensures that the legal basis of legitimacy remains robust and responsive to societal needs.

A critical aspect of the legal framework is its adaptability to changing circumstances. Political systems must balance stability with flexibility, ensuring that laws remain relevant without sacrificing their foundational principles. For instance, the process of constitutional amendment in countries like France requires both parliamentary approval and a referendum, ensuring that changes reflect broad consensus. In contrast, uncodified constitutions, such as the UK’s, rely on parliamentary supremacy, allowing for quicker adaptations but potentially undermining long-term stability. This tension highlights the importance of designing legal frameworks that can evolve while maintaining their legitimacy in the eyes of the governed.

Finally, the legal basis of legitimacy must address the global dimension of political authority. In an era of globalization, international law plays a crucial role in legitimizing the actions of nation-states and transnational organizations. The United Nations Charter, for example, provides a legal framework for collective security and human rights, granting legitimacy to interventions like peacekeeping missions. Similarly, the Paris Agreement on climate change relies on international law to bind states to shared goals, even in the absence of a global enforcement mechanism. By integrating domestic and international legal norms, political systems can enhance their legitimacy in a multipolar world, ensuring that their authority is recognized both at home and abroad.

Mastering Politeness: Simple Tips for Thoughtful and Respectful Communication

You may want to see also

Popular Consent: Role of public approval and elections in legitimizing political authority

Political authority derives much of its legitimacy from the concept of popular consent, a principle deeply rooted in democratic systems. At its core, popular consent asserts that a government’s right to rule is granted by the people it governs. This consent is not merely symbolic; it is actively expressed through mechanisms like elections, public opinion polls, and civic participation. Without this endorsement, even the most powerful regimes risk being perceived as illegitimate, leading to instability and resistance. For instance, the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings underscored the consequences of governing without popular consent, as citizens demanded a voice in their political systems.

Elections serve as the cornerstone of popular consent, providing a structured process for citizens to choose their leaders and hold them accountable. However, not all elections are created equal. For legitimacy to be conferred, elections must be free, fair, and transparent. This means ensuring voter access, preventing fraud, and allowing diverse candidates to compete. Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where record voter turnout and rigorous oversight reinforced the legitimacy of the outcome, despite contentious debates. In contrast, elections in authoritarian regimes often lack these safeguards, rendering them little more than a facade for control.

Public approval, beyond the ballot box, plays a critical role in sustaining political legitimacy. Leaders must maintain a level of trust and support through effective governance, responsiveness to citizen needs, and adherence to democratic norms. For example, leaders like Angela Merkel in Germany maintained high approval ratings by addressing crises such as the 2008 financial collapse and the 2015 refugee crisis with pragmatism and empathy. Conversely, leaders who ignore public sentiment risk erosion of their authority. A practical tip for policymakers: Regularly engage with constituents through town halls, social media, and surveys to gauge and address public concerns.

Comparatively, systems that bypass popular consent, such as monarchies or military dictatorships, often rely on alternative sources of legitimacy, like tradition, force, or religious authority. However, these systems face inherent challenges in maintaining stability in an increasingly democratized world. For instance, the British monarchy has adapted by emphasizing its symbolic role and supporting democratic institutions, thereby retaining public approval. This highlights a key takeaway: while popular consent is not the only form of legitimation, it is uniquely adaptable and resilient in modern political landscapes.

In practice, fostering popular consent requires more than periodic elections. It demands continuous dialogue between rulers and the ruled, inclusive policies, and a commitment to democratic principles. For emerging democracies, this might involve investing in civic education to empower citizens to participate meaningfully. For established democracies, it means addressing issues like voter apathy and disinformation. Ultimately, the strength of political authority rests not just on the act of consent but on the ongoing relationship between the government and its people.

NFL and Politics: Unraveling the Complex Interplay of Sports and Policy

You may want to see also

Historical Legitimacy: How historical narratives and traditions validate political power and governance

Historical narratives and traditions serve as the bedrock for legitimizing political power, often by anchoring governance in a shared, revered past. Consider the British monarchy, where the Crown’s authority is deeply rooted in centuries-old traditions, coronations, and lineage. These rituals are not mere pageantry; they systematically reinforce the monarchy’s right to rule by connecting it to a historical continuity that predates modern political systems. Similarly, the United States leverages its founding documents—the Constitution and Declaration of Independence—to validate its democratic institutions, framing them as the culmination of a revolutionary struggle for liberty. Such narratives create a sense of inevitability and permanence, making political power appear both natural and unassailable.

To harness historical legitimacy effectively, political entities must curate narratives that resonate with their audience’s values and aspirations. For instance, post-apartheid South Africa rewrote its national story to emphasize reconciliation and shared heritage, using the Truth and Commission process to legitimize its new democratic order. This approach required careful selection of historical events and symbols—Nelson Mandela’s release, the first democratic elections—to build a unifying narrative. Practical steps include: (1) identifying key historical milestones that align with current governance goals, (2) integrating these into public discourse through education, media, and commemorations, and (3) fostering cultural practices that reinforce the narrative. Caution, however, must be exercised to avoid oversimplification or exclusion, as this can alienate segments of the population and undermine legitimacy.

A comparative analysis reveals that historical legitimacy is not universally effective. In countries with fragmented histories or contested narratives, such as Iraq or Rwanda, reliance on the past can exacerbate divisions rather than unify. For example, Saddam Hussein’s regime attempted to link itself to ancient Mesopotamian empires, but this failed to legitimize his authoritarian rule in the eyes of many Iraqis. Conversely, nations like Germany have successfully repurposed historical narratives, acknowledging past atrocities while emphasizing post-war reconstruction and democratic values. This highlights the importance of adaptability: historical legitimacy must evolve to address contemporary challenges and societal changes.

Persuasively, historical legitimacy thrives when it is not just asserted but lived. Traditions and narratives must be embodied in institutions and policies to be credible. For instance, Japan’s imperial system maintains legitimacy through meticulous adherence to ancient rituals, while simultaneously adapting to modern governance demands. Similarly, indigenous communities worldwide assert political claims by grounding them in pre-colonial histories and practices, challenging dominant narratives and reclaiming agency. To implement this, governments and movements should: (1) ensure that historical narratives are reflected in tangible policies, (2) involve diverse voices in shaping these narratives, and (3) regularly reassess their relevance in a changing world.

Ultimately, historical legitimacy is a double-edged sword. While it provides a powerful tool for validating political power, it risks becoming a straitjacket if rigidly applied. The key lies in balancing reverence for tradition with the flexibility to address present-day realities. By thoughtfully weaving historical narratives into governance, political entities can foster a sense of continuity and purpose, but they must remain vigilant against the pitfalls of exclusion or stagnation. In an era of rapid change, the past is not just a resource to be mined but a dialogue to be sustained—one that bridges generations and guides the future.

Vomiting with Etiquette: A Guide to Puking Politely in Public

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$35.95

Institutional Trust: Importance of credible institutions in maintaining political legitimacy and stability

Political legitimacy hinges on the perceived fairness and competence of governing institutions. When citizens trust that institutions like courts, legislatures, and electoral bodies operate impartially and effectively, they are more likely to accept their decisions, even when those decisions are unpopular. This trust acts as a social glue, binding diverse populations to a shared system of governance. For instance, the widespread acceptance of the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings, despite ideological divides, underscores the power of institutional credibility in sustaining legitimacy. Without such trust, even the most democratic systems risk descending into polarization and instability.

Building credible institutions requires transparency, accountability, and consistent performance. Transparency ensures that institutional processes are visible and understandable to the public, reducing suspicion of hidden agendas. Accountability mechanisms, such as independent oversight bodies or judicial review, hold institutions responsible for their actions, reinforcing public confidence. Consistent performance, particularly in delivering public goods like security, justice, and economic stability, further solidifies trust. For example, Germany’s post-war reconstruction was anchored by the creation of transparent and accountable institutions, which became pillars of its political legitimacy and stability.

However, maintaining institutional trust is not without challenges. Corruption, inefficiency, and partisan capture can erode credibility rapidly. In countries like Brazil, where corruption scandals have repeatedly implicated high-ranking officials, public trust in institutions has plummeted, leading to political instability and social unrest. Similarly, when institutions fail to adapt to changing societal demands—such as addressing inequality or climate change—their legitimacy suffers. Policymakers must proactively address these vulnerabilities through reforms that prioritize integrity, responsiveness, and inclusivity.

A comparative analysis reveals that countries with high institutional trust tend to exhibit greater political stability and economic resilience. Nordic nations, renowned for their transparent governance and robust welfare systems, consistently rank among the most politically stable and prosperous globally. Conversely, states with weak or compromised institutions often struggle with legitimacy crises, as seen in Venezuela or Zimbabwe. This underscores the importance of investing in institutional strength as a long-term strategy for political survival and societal cohesion.

Practical steps to enhance institutional trust include decentralizing power to reduce the risk of abuse, fostering civic education to inform citizens about institutional roles, and leveraging technology to improve transparency. For instance, Estonia’s e-governance system, which allows citizens to track government decisions and expenditures in real-time, has become a model for building trust through technological innovation. Ultimately, credible institutions are not just tools of governance but the bedrock of a legitimate and stable political order. Without them, even the most well-intentioned policies risk failing to secure public acceptance and support.

Understanding Political Asylum: Process, Rights, and Global Protections Explained

You may want to see also

Performance Legitimacy: How effective governance and policy outcomes reinforce political legitimacy over time

Effective governance isn't just about holding power; it's about earning the right to wield it. This is where performance legitimacy steps in, a concept that ties a government's legitimacy directly to its ability to deliver tangible results. Think of it as a contract: citizens grant authority in exchange for competent leadership, security, and improved well-being. When governments consistently deliver on these fronts, they cultivate a deep-rooted legitimacy that transcends fleeting political cycles.

Historically, performance legitimacy has been a cornerstone of stable regimes. Singapore's transformation from a developing nation to a global economic powerhouse is a prime example. The government's relentless focus on economic growth, efficient public services, and social welfare programs has fostered a strong sense of legitimacy among its citizens. Similarly, Scandinavian countries, known for their robust social safety nets and high living standards, enjoy high levels of public trust in their governments, demonstrating the enduring power of performance legitimacy.

However, achieving performance legitimacy isn't a straightforward endeavor. It requires a delicate balance between short-term gains and long-term sustainability. Governments must resist the temptation to prioritize populist policies that offer immediate gratification but lack lasting impact. Instead, they should invest in infrastructure, education, healthcare, and environmental protection – areas that yield tangible benefits over time. Transparency and accountability are equally crucial. Citizens need to see how their tax dollars are being spent and have avenues to hold leaders accountable for their actions.

Regular evaluation and course correction are essential. Governments should establish clear metrics to measure the effectiveness of their policies and be willing to adapt based on feedback and changing circumstances. This iterative approach ensures that performance legitimacy remains dynamic and responsive to the evolving needs of the population.

Ultimately, performance legitimacy is not a destination but a continuous journey. It demands a commitment to excellence, a willingness to learn from mistakes, and a deep understanding of the needs and aspirations of the people. By prioritizing effective governance and delivering tangible results, governments can build a legitimacy that is both durable and deeply rooted in the trust and support of their citizens.

Is CNN Biased? Analyzing Its Democratic Leanings and Media Integrity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Legitimation in politics refers to the process by which a political system, government, or authority gains acceptance and recognition as rightful and justified in the eyes of its citizens or subjects.

Legitimation is crucial because it ensures stability, compliance, and trust in a political system. Without it, governments may face resistance, rebellion, or a lack of cooperation from the population.

The main sources of legitimation include democratic elections, traditional authority, charismatic leadership, legal frameworks, and ideological or moral justifications that resonate with the population.

Legitimacy refers to the inherent rightfulness or justification of a political system, while legitimation is the active process of establishing or maintaining that perception among the people.

Yes, a government can lose its legitimation if it fails to meet the expectations of its citizens, engages in corruption, violates human rights, or loses its ability to provide basic services and security.