Institutional politics refers to the dynamics, processes, and power structures within formal organizations, such as governments, corporations, or international bodies, that shape decision-making, policy formulation, and resource allocation. It focuses on how rules, norms, and hierarchies within these institutions influence political behavior, often prioritizing organizational goals over individual interests. Unlike traditional politics, which emphasizes elections and public opinion, institutional politics examines the internal mechanisms, bureaucratic procedures, and informal networks that drive outcomes, highlighting how institutions both reflect and reinforce broader political systems. Understanding institutional politics is crucial for analyzing how power operates within structured environments and how these frameworks impact societal outcomes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formal Structures | Government bodies, legislative assemblies, courts, and administrative agencies. |

| Rules and Procedures | Established norms, laws, and protocols governing decision-making processes. |

| Power Distribution | Hierarchical allocation of authority among institutions and officials. |

| Bureaucracy | Organized systems of officials managing public policy and services. |

| Accountability Mechanisms | Checks and balances, elections, audits, and oversight bodies. |

| Policy Formulation | Institutional roles in creating, implementing, and enforcing policies. |

| Stability and Continuity | Enduring frameworks that persist beyond individual leaders or governments. |

| Conflict Resolution | Institutionalized processes for mediating disputes (e.g., courts, parliaments). |

| Representation | Institutions acting as intermediaries between citizens and the state. |

| Legitimacy | Derived from constitutional frameworks, public trust, and legal authority. |

| Adaptability | Ability to evolve through reforms, amendments, or institutional redesign. |

| Inter-Institutional Relations | Dynamics between branches of government (e.g., executive, judiciary, legislature). |

| Global Influence | Role in international institutions (e.g., UN, EU) and global governance. |

| Resource Allocation | Control over budgeting, funding, and resource distribution. |

| Cultural and Normative Role | Shaping societal values, norms, and expectations through institutional practices. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Power Dynamics: How institutions distribute and exercise authority within political systems

- Bureaucratic Influence: Role of administrative bodies in shaping policy and governance

- Formal vs. Informal Rules: Impact of written laws versus unwritten norms in institutions

- Institutional Change: Factors driving evolution or stagnation in political structures

- Accountability Mechanisms: Systems ensuring institutions act in public interest and transparency

Power Dynamics: How institutions distribute and exercise authority within political systems

Institutions are the backbone of political systems, but their true power lies not in their existence, but in how they distribute and wield authority. This distribution is rarely equal; it’s a carefully orchestrated dance of influence, often favoring those who design the rules. Consider the U.S. Electoral College: a system ostensibly created to balance state power, yet critics argue it disproportionately amplifies the influence of smaller, rural states over densely populated urban centers. This imbalance illustrates how institutional design can entrench power dynamics, shaping political outcomes long before votes are cast.

To understand this, dissect the mechanisms institutions employ. Formal rules, such as legislative procedures or constitutional provisions, are the visible framework. Yet, informal norms—unwritten rules like senatorial courtesy or party loyalty—often dictate real authority. For instance, in parliamentary systems, the majority party’s leader becomes the head of government, but their power is tempered by caucus dynamics and backbench dissent. This duality of formal and informal power reveals how institutions both structure and obscure authority, creating layers of control that are difficult to challenge.

A persuasive argument emerges when examining how institutions adapt to maintain dominance. Take central banks: while nominally independent, their policies often align with the interests of financial elites. This is not mere coincidence but a strategic exercise of authority, where institutional autonomy serves as a shield against democratic oversight. Such examples underscore the need for vigilance in scrutinizing how institutions frame their roles, as their neutrality is often a myth perpetuated to safeguard established power structures.

Comparatively, the distribution of authority differs starkly across political systems. In federal systems like Germany, power is diffused across states (Länder), creating a multi-layered governance structure that limits central authority. Contrast this with unitary systems like France, where power is concentrated in a strong central government. These models highlight how institutional design reflects and reinforces cultural, historical, and ideological priorities, shaping not just governance but societal power hierarchies.

Practically, understanding these dynamics empowers citizens to navigate and challenge institutional authority. For instance, knowing that regulatory agencies often face "regulatory capture" by the industries they oversee can inform advocacy for stronger transparency measures. Similarly, recognizing the role of informal norms in decision-making can guide strategies for influencing policy from within. By demystifying how institutions distribute and exercise power, individuals can become more effective agents of change, leveraging knowledge to disrupt entrenched systems and advocate for equitable authority.

Tom Hanks on Politics: His Views, Voice, and Public Stance Explored

You may want to see also

Bureaucratic Influence: Role of administrative bodies in shaping policy and governance

Administrative bodies, often seen as mere cogs in the machinery of government, wield significant influence in shaping policy and governance. Their role extends beyond implementing decisions; they actively interpret, adapt, and sometimes even redirect legislative intent. This bureaucratic influence is rooted in their expertise, procedural control, and proximity to the day-to-day realities of policy execution. For instance, regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States not only enforce laws but also draft regulations that define how those laws are applied, effectively shaping environmental policy in nuanced ways.

Consider the process of rulemaking, a critical function of administrative bodies. While legislatures pass broad statutes, it is often the bureaucrats who translate these into actionable rules. This process involves discretion, as agencies must balance competing interests, interpret ambiguous language, and account for practical constraints. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determines the safety thresholds for new drugs, a decision that directly impacts public health and pharmaceutical innovation. Such decisions are not merely technical; they reflect policy choices that can favor industry, consumer safety, or public health, depending on the agency’s priorities and leadership.

The influence of administrative bodies is further amplified by their role in policy implementation. Bureaucrats are the first line of contact between government and citizens, and their actions can either facilitate or hinder policy goals. For instance, the success of welfare programs often depends on the efficiency and empathy of caseworkers, who interpret eligibility criteria and allocate resources. Similarly, tax compliance is heavily influenced by the clarity of instructions and the responsiveness of revenue agency staff. This operational role gives bureaucrats a unique vantage point to identify policy gaps and propose reforms, making them de facto policymakers in many areas.

However, this influence is not without risks. Bureaucratic inertia, captured interests, and lack of accountability can distort policy outcomes. Agencies may become overly aligned with the industries they regulate, a phenomenon known as regulatory capture, as seen in some financial regulatory bodies during the 2008 financial crisis. To mitigate these risks, oversight mechanisms such as legislative reviews, judicial scrutiny, and public participation in rulemaking are essential. Transparency and accountability must be prioritized to ensure that bureaucratic influence serves the public interest rather than narrow agendas.

In conclusion, administrative bodies are not passive executors of policy but active participants in its creation and implementation. Their expertise, procedural control, and operational insights give them a unique ability to shape governance. While this influence can lead to more effective and practical policies, it also requires robust checks and balances to prevent misuse. Understanding and managing bureaucratic influence is thus critical for anyone seeking to navigate or reform institutional politics.

How Political Affiliations Shaped Our Personal Identities and Divided Us

You may want to see also

Formal vs. Informal Rules: Impact of written laws versus unwritten norms in institutions

Institutions, whether political, corporate, or social, operate on a dual framework of formal and informal rules. Formal rules, codified in written laws, policies, and procedures, provide clarity and structure. They are enforceable, predictable, and serve as the backbone of institutional legitimacy. Informal rules, on the other hand, are unwritten norms, traditions, and behaviors that emerge organically within a group. These norms often dictate how formal rules are interpreted and applied, shaping the culture and power dynamics of an institution. While formal rules establish the "letter of the law," informal rules determine its "spirit," creating a complex interplay that defines institutional politics.

Consider the U.S. Senate, where formal rules like cloture (requiring 60 votes to end debate) are designed to encourage bipartisanship. However, the informal norm of "senatorial courtesy," where senators defer to colleagues from the same state, often influences appointments and legislation. This unwritten rule can either complement or undermine formal procedures, depending on how it is wielded. Similarly, in corporate settings, formal policies on workplace conduct coexist with informal norms like "unspoken hierarchies" or "watercooler politics," which can either reinforce or subvert official guidelines. The tension between these two systems highlights the importance of understanding their symbiotic relationship.

To navigate this duality effectively, institutions must adopt a three-step approach. First, audit both rule systems by mapping formal policies and observing informal behaviors. For instance, a university might review its anti-discrimination policies while also conducting anonymous surveys to uncover unreported biases. Second, align formal and informal rules where possible. If informal norms contradict formal policies—such as a culture of overtime in a company that officially promotes work-life balance—address the discrepancy through training or incentives. Third, leverage informal norms strategically. Recognize that unwritten rules can expedite decision-making or foster cohesion. For example, a leader who embodies the informal norm of transparency can strengthen trust in formal accountability mechanisms.

However, this approach comes with cautions. Over-reliance on informal norms can lead to exclusionary practices or favoritism, particularly in diverse institutions. For instance, a "good ol’ boys" network in a government agency may sideline qualified outsiders despite formal merit-based hiring rules. Conversely, rigid adherence to formal rules without considering informal context can alienate stakeholders. A hospital implementing strict patient discharge protocols without accounting for nurses’ informal knowledge of patient needs may face resistance and inefficiency. Balancing the two requires nuance, not absolutism.

Ultimately, the impact of formal versus informal rules hinges on their interaction. Formal rules provide stability and fairness, but informal norms infuse institutions with flexibility and humanity. A well-functioning institution recognizes that written laws are necessary but insufficient; unwritten norms fill the gaps, interpret ambiguities, and humanize systems. By understanding and managing this dynamic, leaders can foster institutions that are both structured and adaptive, equitable and empathetic. The key lies not in prioritizing one over the other but in orchestrating their harmony.

Imperfectability in Politics: Navigating Flawed Systems for Better Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Institutional Change: Factors driving evolution or stagnation in political structures

Institutional politics refers to the formal and informal rules, norms, and structures that govern how power is exercised and decisions are made within organizations, governments, and societies. At its core, it examines how institutions shape behavior, allocate resources, and maintain order. However, institutions are not static; they evolve or stagnate in response to internal and external pressures. Understanding the factors driving institutional change is crucial for predicting political trajectories and fostering adaptive governance.

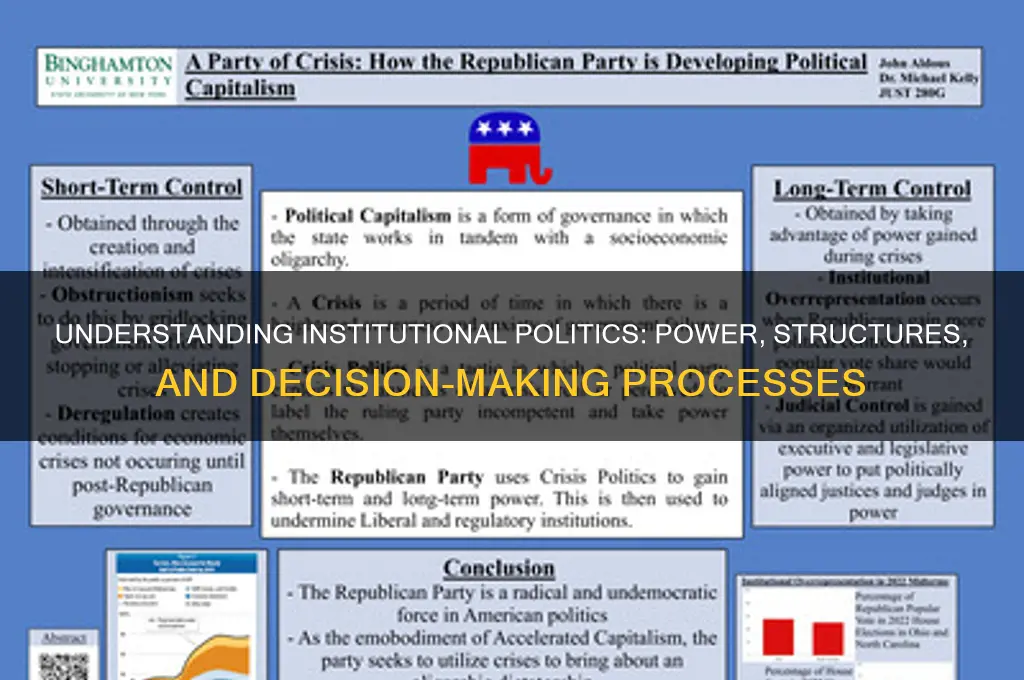

Consider the role of crises as catalysts for institutional evolution. Historical examples, such as the Great Depression leading to the creation of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, illustrate how systemic failures force reevaluation of existing structures. Crises expose vulnerabilities, creating political momentum for reform. However, not all crises result in change; the presence of agency—whether from leaders, social movements, or international actors—is essential to translate crisis into transformation. For instance, the 2008 financial crisis prompted regulatory reforms in some countries but not others, highlighting the interplay between crisis and strategic action.

In contrast, path dependency often drives institutional stagnation. Once established, institutions create self-reinforcing mechanisms that resist change. Bureaucratic inertia, vested interests, and cultural norms can entrench outdated structures. Take the case of electoral systems: first-past-the-post systems in countries like the U.K. and the U.S. persist despite criticisms of disproportionality because altering them would require overcoming entrenched party interests and public unfamiliarity with alternatives. Breaking free from path dependency requires deliberate efforts, such as incremental reforms or external shocks, to disrupt the status quo.

Another critical factor is ideological shifts, which can either propel or hinder institutional change. When dominant ideologies align with reformist agendas, institutions adapt more readily. For example, the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s led to widespread privatization and deregulation across Western democracies. Conversely, ideological polarization can paralyze reform efforts, as seen in contemporary debates over healthcare or climate policy. Policymakers must navigate these ideological currents, often by framing reforms in ways that resonate with prevailing beliefs or by building cross-ideological coalitions.

Finally, technological advancements are reshaping institutions in unprecedented ways. Digitalization has transformed governance, from e-voting systems to data-driven policymaking. However, technology’s impact is not uniformly positive; it can also exacerbate inequalities or create new vulnerabilities, such as cyber threats to electoral integrity. Institutions must proactively adapt to technological realities, balancing innovation with safeguards to ensure inclusivity and accountability. For instance, Estonia’s e-governance model demonstrates how technology can enhance institutional efficiency when paired with robust cybersecurity measures.

In navigating institutional change, leaders and reformers must recognize the complex interplay of crises, path dependency, ideology, and technology. While crises offer opportunities for bold reform, they require strategic agency to capitalize on. Overcoming stagnation demands addressing entrenched interests and leveraging incremental steps. Ideological shifts provide both challenges and openings, necessitating nuanced framing and coalition-building. Meanwhile, technological advancements offer tools for modernization but require careful management to avoid unintended consequences. By understanding these dynamics, stakeholders can foster institutions that are resilient, adaptive, and responsive to societal needs.

Navigating Political Conversations: Strategies for Therapists to Stay Neutral and Effective

You may want to see also

Accountability Mechanisms: Systems ensuring institutions act in public interest and transparency

Institutions, whether governmental, corporate, or non-profit, wield significant power in shaping public life. Without robust accountability mechanisms, this power can be misused, leading to corruption, inefficiency, and erosion of public trust. Accountability mechanisms are the checks and balances that ensure institutions act in the public interest and maintain transparency. These systems are not just bureaucratic formalities; they are the backbone of democratic governance and ethical organizational behavior.

Consider the role of independent oversight bodies as a cornerstone of accountability. Entities like ombudsmen, audit commissions, and anti-corruption agencies operate outside the institutions they monitor, providing impartial scrutiny. For instance, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducts audits and investigations to ensure federal agencies comply with laws and use resources efficiently. Similarly, in the corporate sector, external auditors assess financial statements to verify accuracy and compliance with regulations. These bodies serve as watchdogs, deterring misconduct and providing avenues for redress when violations occur.

Transparency is another critical component of accountability mechanisms. Public disclosure requirements mandate that institutions share information about their operations, decisions, and performance. For example, governments often publish budgets, meeting minutes, and policy documents online, allowing citizens to monitor how public funds are spent. In the private sector, companies listed on stock exchanges must file regular reports with regulatory bodies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), ensuring investors and stakeholders have access to vital information. Transparency not only fosters trust but also enables informed public participation in decision-making processes.

However, accountability mechanisms are only effective if they are enforced with consequences. Sanctions, penalties, and legal actions must follow identified wrongdoing to deter future misconduct. For instance, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes hefty fines on companies that mishandle personal data, incentivizing compliance. Similarly, in public institutions, officials found guilty of corruption may face criminal charges, removal from office, or bans from public service. Without such consequences, accountability systems risk becoming toothless, allowing institutions to act with impunity.

Finally, citizen engagement is a powerful tool for holding institutions accountable. Public hearings, consultations, and feedback mechanisms allow individuals to voice concerns and influence decisions. For example, participatory budgeting initiatives in cities like Porto Alegre, Brazil, enable residents to directly allocate a portion of municipal funds, ensuring resources align with community needs. Social media and digital platforms have also amplified citizen voices, allowing for real-time scrutiny of institutional actions. By actively involving the public, accountability mechanisms become more dynamic and responsive to societal demands.

In practice, designing effective accountability mechanisms requires a balance between independence, transparency, enforcement, and participation. Institutions must embrace these systems not as burdens but as essential tools for legitimacy and public trust. Without them, the promise of acting in the public interest remains an empty slogan, vulnerable to abuse and neglect. Accountability is not just a principle—it is a practice that sustains the integrity of institutions and the societies they serve.

Political Machines: Shaping Urban Landscapes and City Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Institutional politics refers to the processes, structures, and norms within formal organizations or governing bodies that shape decision-making, power dynamics, and policy outcomes. It focuses on how institutions like governments, corporations, or international bodies operate and influence political behavior.

Institutional politics is distinct because it emphasizes the role of formal rules, procedures, and organizations in shaping political outcomes, whereas other forms of politics, like grassroots or identity politics, focus on informal movements, ideologies, or social groups.

Institutional politics is crucial because it provides the framework for stable and predictable decision-making, ensures accountability, and mediates conflicts within organizations or governments. It also determines how power is distributed and exercised within formal systems.

Yes, institutional politics significantly influences policy outcomes by dictating how decisions are made, who has a say in the process, and how resources are allocated. The design of institutions, such as legislative bodies or regulatory agencies, often determines the direction and effectiveness of policies.