An independent party in politics refers to a political organization or candidate that operates outside the traditional two-party system or dominant political parties in a given country. Unlike members of established parties, independents do not align with a specific party platform, allowing them greater flexibility to advocate for diverse or non-partisan issues. This independence can appeal to voters disillusioned with party politics, as it often emphasizes individual principles, local concerns, or cross-party collaboration. However, independents may face challenges in fundraising, gaining media attention, and securing legislative influence compared to their party-affiliated counterparts. Their presence in political systems can highlight the limitations of partisan politics and offer alternative voices in governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political party or candidate not affiliated with any major established party. |

| Autonomy | Operates independently, free from control by larger political organizations. |

| Ideological Flexibility | Often holds diverse or non-aligned policy positions, not bound by party doctrine. |

| Grassroots Support | Relies on local or individual support rather than national party structures. |

| Funding Sources | Typically funded by individual donors, small contributions, or self-funding. |

| Electoral Strategy | Focuses on local issues, personal appeal, or anti-establishment messaging. |

| Representation | May represent niche interests, regional concerns, or disillusioned voters. |

| Legislative Behavior | Tends to vote independently or cross-party based on issue-by-issue merit. |

| Global Examples | Independents exist in various democracies (e.g., U.S., UK, Australia). |

| Challenges | Faces barriers like limited resources, media coverage, and ballot access. |

| Impact | Can influence elections, disrupt two-party systems, or amplify minority voices. |

Explore related products

$19.23 $24.95

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Core Principles: Independent parties operate outside major party structures, emphasizing autonomy and diverse ideologies

- Historical Context: Origins trace back to anti-establishment movements, challenging two-party dominance in politics

- Electoral Strategies: Independents focus on grassroots campaigns, direct voter engagement, and issue-based appeals

- Challenges Faced: Limited funding, media coverage, and ballot access hinder independent party growth

- Global Examples: Independent parties exist worldwide, e.g., UK’s Brexit Party, Australia’s Independents

Definition and Core Principles: Independent parties operate outside major party structures, emphasizing autonomy and diverse ideologies

Independent parties, by definition, stand apart from the established political duopolies or dominant coalitions that often characterize national politics. Unlike major parties, which are typically bound by rigid platforms and hierarchical structures, independent parties prioritize autonomy and ideological diversity. This distinction is not merely semantic; it reflects a fundamental difference in how these parties engage with voters and approach governance. For instance, while major parties often require members to adhere to a predefined set of policies, independent parties may allow candidates to champion a broader spectrum of ideas, from environmental sustainability to localized economic reforms. This flexibility enables them to appeal to voters disillusioned with the binary choices offered by traditional politics.

Consider the practical implications of this autonomy. Independent parties often emerge as responses to specific issues or grievances that major parties fail to address adequately. For example, the rise of independent candidates in recent U.S. elections, such as Senator Bernie Sanders (though technically running as a Democrat, his campaign ethos aligns with independent principles), highlights a growing appetite for alternatives to the status quo. Similarly, in countries like the UK, independent candidates have gained traction by focusing on hyper-local issues, such as infrastructure development or healthcare access, which major parties often overlook in favor of national-level agendas. This issue-driven approach not only differentiates independent parties but also allows them to act as catalysts for change within stagnant political systems.

However, autonomy comes with challenges. Without the financial and organizational backing of major parties, independent candidates often face uphill battles in fundraising, media coverage, and voter outreach. To overcome these hurdles, many independent parties adopt grassroots strategies, leveraging social media and community engagement to amplify their message. For instance, a practical tip for independent candidates is to focus on building coalitions with local organizations and leveraging crowdfunding platforms to finance campaigns. Additionally, emphasizing transparency and accountability can help build trust with voters who are skeptical of traditional political institutions.

A comparative analysis reveals that independent parties are not a monolithic entity but rather a spectrum of movements tailored to their contexts. In India, for example, independent candidates often represent marginalized communities or advocate for regional autonomy, while in European countries like Germany, independent parties may focus on cross-cutting issues like digital privacy or climate policy. This adaptability is a core strength, allowing independent parties to resonate with diverse electorates. However, it also underscores the need for clarity in messaging to avoid dilution of their core principles.

In conclusion, the essence of independent parties lies in their ability to transcend the limitations of major party structures, offering voters a more personalized and issue-focused alternative. While their autonomy and ideological diversity are strengths, they must navigate practical challenges to remain viable. By embracing innovative campaign strategies and staying true to their principles, independent parties can carve out a meaningful space in the political landscape, challenging the dominance of traditional parties and fostering a more inclusive democracy.

Can National Parties Fund State Elections? Legal Insights and Limits

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Origins trace back to anti-establishment movements, challenging two-party dominance in politics

The roots of independent political parties are deeply embedded in anti-establishment movements that have historically sought to disrupt the stranglehold of two-party systems. In the United States, for instance, the emergence of the Anti-Masonic Party in the 1820s marked one of the earliest organized challenges to the dominant Democratic and Whig parties. This movement, fueled by suspicions of Freemasonry’s influence on politics, demonstrated how single-issue concerns could galvanize voters outside the traditional party framework. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the Chartist movement of the mid-19th century demanded political reforms, laying the groundwork for later independent and third-party efforts to challenge the Conservative-Liberal duopoly.

These early movements were not merely protests but strategic attempts to redefine political participation. By organizing outside the established parties, they sought to amplify voices marginalized by the two-party system. For example, the Progressive Party in the U.S., founded in 1912 by Theodore Roosevelt, exemplified this approach. Frustrated by the Republican Party’s conservatism, Roosevelt’s "Bull Moose" campaign championed reforms like women’s suffrage and antitrust legislation, attracting millions of voters and demonstrating the viability of independent platforms. Such efforts underscored the potential of anti-establishment movements to reshape political discourse.

Globally, independent parties have often arisen in response to systemic failures of two-party systems. In India, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), founded in 2012, emerged from the anti-corruption movement led by Anna Hazare. AAP’s success in local and state elections highlighted how independent parties could capitalize on public disillusionment with entrenched political elites. Similarly, in Latin America, movements like Mexico’s Morena party, born from protests against corruption and inequality, have disrupted traditional party structures by offering alternative governance models.

However, the historical trajectory of independent parties is not without challenges. Their success often hinges on charismatic leadership, as seen with figures like Roosevelt or Arvind Kejriwal of AAP. Without such figures, these movements risk fragmentation or co-optation by established parties. Additionally, their ability to sustain momentum depends on translating anti-establishment sentiment into concrete policy proposals. For instance, the Reform Party in the U.S., which gained traction in the 1990s, struggled to maintain relevance after its initial successes due to internal divisions and a lack of cohesive policy vision.

In analyzing these historical contexts, a key takeaway emerges: independent parties thrive when they channel widespread discontent into actionable agendas. They must balance ideological purity with pragmatic governance, ensuring they remain distinct from the parties they seek to challenge. For activists or voters considering supporting such movements, it’s crucial to assess their organizational strength, policy clarity, and long-term viability. By studying these historical examples, one can better understand how independent parties have—and can continue to—reshape political landscapes.

Penn & Teller's Political Party: Unveiling Their Surprising Affiliation

You may want to see also

Electoral Strategies: Independents focus on grassroots campaigns, direct voter engagement, and issue-based appeals

Independent candidates often bypass traditional party machinery, relying instead on grassroots campaigns to build momentum. This approach involves mobilizing local volunteers, leveraging community networks, and hosting small-scale events like town halls or door-to-door canvassing. For instance, in the 2018 U.S. Senate race, Angus King of Maine secured victory by focusing on rural areas often overlooked by major parties. His strategy included attending county fairs and hosting "kitchen table" discussions, fostering personal connections that resonated with voters. This method, while labor-intensive, allows independents to compete without the financial backing of established parties.

Direct voter engagement is another cornerstone of independent campaigns. Unlike party-affiliated candidates, who often rely on scripted messaging, independents thrive on authenticity. They use social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram to respond directly to voter concerns, often sharing unpolished videos or live Q&A sessions. For example, during the 2019 UK general election, independent candidate Jane Dodds gained traction by live-streaming her daily campaign activities, including impromptu conversations with constituents. This transparency builds trust, a critical asset for candidates without a party brand to fall back on.

Issue-based appeals differentiate independents from partisan candidates, who often prioritize party platforms over specific concerns. Independents can tailor their messages to local or niche issues, such as water rights in arid regions or public transportation in urban centers. In the 2020 U.S. House race, independent candidate Jared Golden of Maine focused on healthcare affordability and opioid crisis solutions, issues that transcended party lines. By framing their campaigns around actionable solutions rather than ideological stances, independents attract voters disillusioned with partisan gridlock.

However, these strategies are not without challenges. Grassroots campaigns require significant time and organizational skill, while direct engagement can expose candidates to scrutiny or backlash. Issue-based appeals, though effective, risk alienating voters if not carefully calibrated. For instance, an independent candidate focusing solely on environmental policy might struggle to appeal to voters prioritizing economic concerns. Balancing specificity with broad appeal is crucial, as is maintaining a consistent message across diverse audiences.

To maximize effectiveness, independents should adopt a multi-pronged approach. Start by identifying 2–3 key issues that resonate with the target demographic, supported by data from local surveys or focus groups. Allocate at least 40% of campaign resources to grassroots efforts, such as volunteer training and community events. Use digital tools like CRM software to track voter interactions and tailor follow-up communications. Finally, establish a rapid response team to address criticism or misinformation, ensuring the campaign remains focused on its core message. By combining these tactics, independents can overcome structural disadvantages and compete effectively in electoral races.

Understanding Power, Wealth, and Society: Why Study Political Economy?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Challenges Faced: Limited funding, media coverage, and ballot access hinder independent party growth

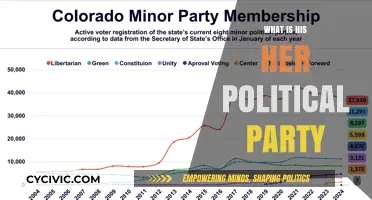

Independent parties, by definition, operate outside the established two-party system, offering voters an alternative to the dominant political forces. However, this independence comes at a steep price. One of the most significant barriers to their growth is limited funding. Unlike major parties, which have established donor networks, corporate backers, and access to large-scale fundraising events, independent parties often rely on small, individual contributions. This financial disparity is stark: in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, the Democratic and Republican candidates raised over $1 billion each, while independent candidates struggled to reach even 1% of that figure. Without substantial funding, independent parties cannot afford the campaign infrastructure—staff, advertising, travel—necessary to compete effectively.

Compounding the funding issue is the challenge of media coverage. Mainstream media outlets tend to focus on the horse-race dynamics between the two major parties, leaving little room for independent voices. A study by the Pew Research Center found that independent candidates receive less than 5% of total election coverage, even in races where they are viable contenders. This lack of visibility creates a vicious cycle: without media attention, independent parties struggle to gain recognition, and without recognition, they remain on the fringes of political discourse. For instance, despite Ross Perot’s strong showing in the 1992 U.S. presidential election, his Reform Party failed to sustain momentum due to limited media interest in subsequent cycles.

Ballot access is another critical hurdle. In the U.S., independent candidates must navigate a patchwork of state-specific requirements to appear on the ballot, which can include gathering tens of thousands of signatures, paying exorbitant fees, or meeting arbitrary deadlines. These barriers are intentionally designed to favor established parties. For example, in Texas, an independent presidential candidate must collect over 80,000 signatures, while in Oklahoma, the requirement is just 3% of the total votes cast in the last gubernatorial election. Such disparities make it nearly impossible for independent parties to compete on a national scale, effectively limiting their reach to a handful of states.

To overcome these challenges, independent parties must adopt innovative strategies. Crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe and Patreon can help bridge the funding gap by tapping into grassroots support. Leveraging social media and digital advertising allows them to bypass traditional media gatekeepers, though this requires significant time and expertise. For ballot access, coalitions with like-minded groups and legal challenges to restrictive laws can create pathways to participation. While these solutions are not foolproof, they offer a roadmap for independent parties to amplify their voices in a system stacked against them. Without addressing these structural barriers, true political diversity will remain an elusive goal.

Philosophy, Politics, and Economics: Unraveling the Interconnectedness of Society

You may want to see also

Global Examples: Independent parties exist worldwide, e.g., UK’s Brexit Party, Australia’s Independents

Independent parties, often seen as disruptors in traditional political landscapes, have carved out significant roles across the globe. One notable example is the UK’s Brexit Party, founded in 2019 by Nigel Farage. This party emerged as a single-issue force, solely focused on ensuring the UK’s exit from the European Union. Its rapid rise—securing 29 out of 73 UK seats in the 2019 European Parliament elections—demonstrates how independent parties can capitalize on public frustration with mainstream politics. The Brexit Party’s success underscores the power of a clear, focused agenda in mobilizing voters disillusioned with established parties.

In contrast, Australia’s independent movement operates differently, often emphasizing local issues and personal integrity over national ideologies. Australian independents, like Helen Haines and Zali Steggall, have gained traction by addressing community-specific concerns such as climate change, healthcare, and rural development. Unlike the Brexit Party’s centralized leadership, Australian independents thrive on their ability to connect directly with constituents, often running on platforms tailored to their electorates. This localized approach highlights how independent parties can succeed by prioritizing grassroots engagement over broad, sweeping manifestos.

Comparing these two models reveals distinct strategies for independent party success. The Brexit Party’s top-down approach leveraged media visibility and a singular, polarizing issue to achieve rapid national impact. Conversely, Australian independents adopt a bottom-up strategy, building support through personal relationships and hyper-local advocacy. Both approaches, however, share a common thread: they fill voids left by major parties, whether by addressing ignored issues or offering an alternative to partisan gridlock.

For those considering supporting or forming an independent party, the takeaway is clear: success hinges on understanding the electorate’s unmet needs. Single-issue parties like the Brexit Party thrive by offering a clear solution to a pressing problem, while locally focused independents succeed by embedding themselves in their communities. Practical tips include conducting thorough constituency research, leveraging social media for direct voter engagement, and maintaining transparency to build trust. Whether through a centralized or decentralized model, independent parties prove that political influence isn’t solely the domain of established parties.

The Era of Good Feelings: Which Political Party Held Dominance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An independent party in politics refers to a political party or candidate that operates outside the traditional major party structures, such as Democrats or Republicans in the United States. Independents often advocate for policies or principles that are not aligned with the mainstream parties.

An independent party differs from a major political party in that it typically lacks the widespread organizational structure, funding, and established voter base of major parties. Independents often focus on specific issues or represent niche ideologies rather than a broad platform.

Yes, an independent candidate can win a major political office, though it is less common due to the advantages enjoyed by candidates from major parties. Examples include Senator Bernie Sanders in the U.S., who identifies as an independent but caucuses with Democrats.

The advantages of being an independent party or candidate include the freedom to advocate for policies without being bound by party lines, the ability to appeal to voters disillusioned with major parties, and the potential to bring attention to overlooked issues.

Independent parties or candidates are more common in countries with proportional representation systems or where voter dissatisfaction with major parties is high. They are less prevalent in two-party dominant systems like the United States but still exist as alternatives.