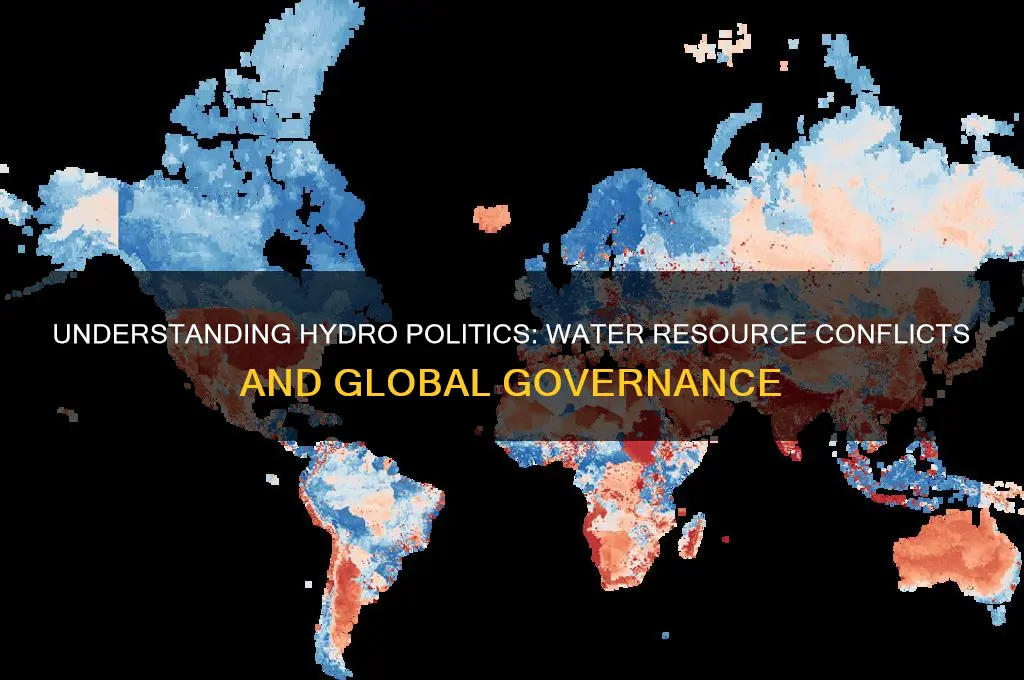

Hydropolitics refers to the study of political interactions surrounding water resources, particularly in the context of transboundary rivers, lakes, and aquifers. As water scarcity intensifies due to climate change, population growth, and increasing demand, it has become a critical resource, often leading to conflicts or cooperation among nations sharing the same water systems. Hydropolitics examines how states negotiate, manage, and sometimes compete for access to water, balancing national interests with regional stability. It also explores the role of international law, treaties, and institutions in mediating disputes and fostering sustainable water governance. Understanding hydropolitics is essential for addressing global water challenges and ensuring equitable access to this vital resource.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Hydro politics refers to the political interactions, conflicts, and cooperation surrounding water resources, including rivers, lakes, and aquifers, often involving transboundary issues. |

| Key Issues | Water scarcity, equitable distribution, pollution, dam construction, and climate change impacts. |

| Stakeholders | Governments, international organizations, local communities, NGOs, and corporations. |

| Transboundary Nature | Involves shared water resources across multiple countries, leading to potential disputes or cooperation. |

| Examples of Conflicts | Nile River Basin (Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan), Indus River (India, Pakistan), Tigris-Euphrates (Turkey, Syria, Iraq). |

| Examples of Cooperation | Mekong River Commission, International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River. |

| Legal Frameworks | United Nations Watercourses Convention, bilateral and multilateral treaties. |

| Economic Impact | Water resources influence agriculture, energy production (hydropower), and industrial development. |

| Environmental Concerns | Ecosystem degradation, loss of biodiversity, and water pollution due to overuse or mismanagement. |

| Climate Change Role | Increasing water stress due to changing precipitation patterns, melting glaciers, and rising temperatures. |

| Technological Influence | Advances in water management technologies, desalination, and irrigation systems shape hydro politics. |

| Social Implications | Access to clean water affects public health, livelihoods, and migration patterns. |

| Geopolitical Significance | Water resources are often leveraged as strategic assets in regional and global politics. |

| Future Trends | Growing emphasis on sustainable water management, international cooperation, and adaptive policies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Water Scarcity and Conflict

Water scarcity exacerbates tensions between communities, regions, and nations, transforming a basic resource into a flashpoint for conflict. The Tigris-Euphrates river basin, shared by Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, exemplifies this dynamic. Turkey’s construction of the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP), a series of dams and irrigation systems, has reduced downstream water flow by 40%, crippling agriculture in Syria and Iraq. This hydrological imbalance has fueled diplomatic disputes and heightened regional instability, illustrating how unilateral water management can become a geopolitical weapon.

To mitigate such conflicts, international frameworks like the United Nations Watercourses Convention emphasize equitable water-sharing and cooperation. However, only 36 countries have ratified it, leaving many transboundary rivers—such as the Nile, shared by 11 nations—vulnerable to disputes. Egypt, reliant on the Nile for 90% of its water, has historically opposed upstream projects like Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam, which threatens to reduce its water supply. This standoff highlights the need for binding agreements and dispute-resolution mechanisms to prevent water scarcity from escalating into armed conflict.

At the local level, water scarcity often ignites intra-community violence, particularly in rural areas dependent on agriculture. In India’s Maharashtra state, competition over dwindling groundwater has led to farmer clashes and even murders. Similarly, in Kenya’s Turkana region, pastoralist communities have engaged in deadly conflicts over shrinking water sources. These instances underscore the importance of decentralized water management strategies, such as rainwater harvesting and community-led conservation efforts, to reduce friction and build resilience.

Addressing water scarcity-driven conflicts requires a multi-faceted approach. First, invest in infrastructure like desalination plants and wastewater recycling systems to augment supply. Israel, for instance, meets 85% of its water needs through desalination. Second, implement policies that incentivize water efficiency in agriculture, which consumes 70% of global freshwater. Third, foster cross-border collaboration through joint research, data-sharing, and joint management bodies. By treating water as a shared resource rather than a zero-sum commodity, societies can transform scarcity from a source of conflict into a catalyst for cooperation.

Politics for a Better World: Shaping Society Through Governance and Action

You may want to see also

Transboundary River Management

Consider the Nile River Basin, shared by 11 countries, where upstream nations like Ethiopia seek to harness its hydroelectric potential through projects like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, while downstream Egypt fears reduced water flow for its agriculture-dependent economy. Such scenarios highlight the need for cooperative frameworks that prioritize equitable water distribution and mutual benefits. International law, including the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, provides a foundation for negotiation, but its effectiveness depends on political will and regional cooperation. Without collaborative mechanisms, transboundary rivers can become sources of tension rather than cooperation.

Implementing successful transboundary river management requires a multi-step approach. First, establish joint institutions like river basin commissions to facilitate dialogue and data sharing among riparian states. Second, develop agreements that outline fair water allocation, pollution control measures, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Third, integrate environmental considerations by setting ecological flow requirements to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem health. For instance, the Mekong River Commission has adopted guidelines to balance hydropower development with fish migration needs, demonstrating how technical solutions can align with ecological goals.

However, challenges persist, including power asymmetries among riparian states, inadequate funding, and climate change impacts. Upstream countries often hold greater control over water flow, while downstream nations bear the brunt of reduced availability or pollution. To mitigate these risks, international donors and organizations like the World Bank can play a pivotal role by providing financial and technical support. Additionally, incorporating adaptive management strategies can help address uncertainties posed by changing climate patterns, ensuring resilience in water governance.

Ultimately, transboundary river management is not just a technical or legal issue but a test of political cooperation and shared vision. By fostering trust, transparency, and mutual respect, riparian states can transform shared rivers into catalysts for regional stability and prosperity. The Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, despite geopolitical tensions, stands as a testament to the potential of diplomacy in managing transboundary waters. As global water demand rises, the lessons from such examples will become increasingly vital for navigating the complexities of hydro politics.

The Rise, Fall, and Future of Politico: What Really Happened?

You may want to see also

Dams and Geopolitical Tensions

Dams, often hailed as symbols of development and progress, have increasingly become flashpoints for geopolitical tensions. Their construction on transboundary rivers can disrupt water flow, affecting downstream nations that depend on these rivers for agriculture, industry, and drinking water. The Nile River, for instance, has been a source of contention between Egypt and Ethiopia since the latter began constructing the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in 2011. Egypt, which relies on the Nile for 90% of its freshwater, fears reduced water supply, while Ethiopia views the dam as critical for its economic growth and electrification. This standoff illustrates how dams can escalate into diplomatic crises, with negotiations often stalling over water-sharing agreements and operational control.

To mitigate such tensions, international frameworks like the United Nations Watercourses Convention emphasize equitable and reasonable utilization of shared water resources. However, these agreements are often non-binding, leaving room for unilateral actions. For example, Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP), which includes 22 dams on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, has strained relations with downstream Iraq and Syria. The project has reduced water flow by up to 80% in some areas, exacerbating water scarcity in these already conflict-prone regions. This highlights the need for stronger enforcement mechanisms and regional cooperation to prevent water from becoming a tool of political leverage.

From a strategic perspective, dams can also serve as instruments of power projection. India’s construction of dams on rivers like the Chenab, which flows into Pakistan, has been criticized by Islamabad as a means to control water flow and exert pressure during political disputes. Similarly, China’s extensive dam-building on the Mekong River has raised concerns among Southeast Asian nations, who accuse Beijing of manipulating water levels to advance its geopolitical interests. Such actions underscore the dual nature of dams—as both developmental assets and potential weapons in hydro-political conflicts.

Practical steps to address these tensions include joint management of transboundary rivers, data-sharing agreements, and dispute resolution mechanisms. For instance, the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, though strained, has largely prevented water-related conflicts since 1960. Additionally, investing in water-efficient technologies and alternative energy sources can reduce reliance on dams, easing geopolitical pressures. For policymakers, the key takeaway is clear: dams are not just engineering projects but geopolitical tools that require careful diplomacy and collaborative governance to avoid escalating tensions.

Understanding Political Persecution: Causes, Impact, and Global Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Water Rights and Equity

Water scarcity affects over 2 billion people globally, yet access to clean water remains unevenly distributed, often exacerbating social and economic inequalities. This disparity is not merely a natural phenomenon but a product of political, economic, and historical factors embedded in hydro politics. Water rights and equity demand a reexamination of how societies allocate this vital resource, ensuring that marginalized communities are not left behind. Without equitable distribution, water scarcity becomes a tool of oppression, deepening divides between the privileged and the underserved.

Consider the case of the Colorado River in the United States, where water rights are allocated based on a "first in time, first in right" principle. This system, established in the early 20th century, prioritizes senior users, often large agricultural interests, over junior users, including growing urban populations and Indigenous communities. The result? Tribes like the Navajo Nation, whose ancestral lands border the river, face severe water shortages while others thrive. Addressing such inequities requires not only policy reform but also acknowledgment of historical injustices. Practical steps include renegotiating water-sharing agreements, investing in infrastructure for underserved areas, and involving Indigenous leaders in decision-making processes.

Globally, the concept of water equity is gaining traction, but implementation remains challenging. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, women and children bear the brunt of water scarcity, often walking miles daily to collect water from unsafe sources. Here, equity means more than access—it entails ensuring water quality, affordability, and sustainability. Solutions like community-managed water kiosks, solar-powered pumps, and rainwater harvesting systems can alleviate these burdens. However, success hinges on local participation and government accountability. Donors and NGOs must avoid top-down approaches, instead empowering communities to own and maintain these systems.

A persuasive argument for water equity lies in its economic and social benefits. Studies show that every $1 invested in water and sanitation yields $4 in economic returns, primarily through reduced healthcare costs and increased productivity. Yet, funding for water projects often bypasses the neediest regions due to political instability or lack of infrastructure. Policymakers must prioritize equity by directing resources to areas with the greatest need, even if it means challenging entrenched interests. For example, South Africa’s constitutional recognition of water as a human right has led to innovative programs like free basic water allocations for low-income households, a model worth replicating globally.

In conclusion, water rights and equity are not abstract ideals but actionable goals requiring deliberate strategies. By addressing historical injustices, involving marginalized communities, and prioritizing economic efficiency, societies can move toward a more just distribution of water. The challenge is immense, but the alternative—a world where water deepens inequality—is unacceptable. Equity in water is not just a moral imperative; it is a foundation for sustainable development and social cohesion.

Mastering Polite Persistence: Effective Strategies to Insist with Grace and Respect

You may want to see also

Climate Change Impact on Water Politics

Climate change is reshaping the global water landscape, intensifying competition over this vital resource and amplifying existing tensions in hydro politics. Rising temperatures alter precipitation patterns, leading to more frequent and severe droughts in some regions while causing devastating floods in others. For instance, the Indus River Basin, shared by India and Pakistan, faces reduced glacial meltwater due to warming, threatening agricultural productivity and exacerbating political friction. Similarly, the Nile River, a lifeline for Egypt and Ethiopia, is at the center of a dispute over Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam, with climate-induced water scarcity heightening stakes for all parties involved.

To navigate these challenges, policymakers must adopt adaptive water management strategies that account for climate variability. This includes investing in infrastructure like reservoirs and desalination plants, as seen in water-stressed countries like Israel and Singapore. However, such solutions are costly and often beyond the reach of developing nations, widening the gap between water-rich and water-poor states. International cooperation is essential, but historical mistrust and competing national interests frequently hinder progress. For example, the Mekong River Commission, which includes Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, struggles to balance hydropower development with downstream water needs, a conflict exacerbated by erratic rainfall patterns linked to climate change.

A persuasive argument can be made for integrating climate resilience into transboundary water agreements. Treaties must evolve to include flexible mechanisms that account for shifting water availability, such as dynamic water-sharing formulas based on real-time data. The 1997 UN Watercourses Convention provides a framework, but its ratification remains limited. Regional bodies like the African Ministers’ Council on Water (AMCOW) are pushing for climate-smart policies, but implementation requires political will and financial support. Without such measures, water scarcity could become a catalyst for conflict, as seen in the Syrian civil war, where drought-driven migration fueled social unrest.

Comparatively, successful models of cooperation offer hope. The Senegal River Basin Organization, involving Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal, demonstrates how joint management can mitigate climate risks. By prioritizing equitable water distribution and sustainable development, the organization has avoided major disputes despite increasing water stress. Such examples highlight the importance of trust-building and shared benefits in hydro politics. However, replicating these successes requires addressing power asymmetries and ensuring all stakeholders, including local communities, have a voice in decision-making.

In conclusion, climate change is not just an environmental issue but a geopolitical one, with water at its core. The impact on hydro politics demands urgent, innovative, and inclusive solutions. From adaptive infrastructure to flexible treaties, the tools exist, but their implementation hinges on global cooperation and equitable resource allocation. As water scarcity deepens, the question is not whether conflicts will arise, but whether nations can rise above self-interest to secure this shared resource for future generations.

Understanding Electioneering: Strategies, Impact, and Role in Modern Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hydro politics refers to the political interactions, conflicts, and cooperation among states or regions over the use, management, and control of water resources, particularly transboundary rivers, lakes, and aquifers.

Hydro politics is crucial because water is a vital resource for agriculture, industry, energy, and human survival. Disputes over water can lead to tensions, conflicts, or even wars, while effective cooperation can foster regional stability and development.

Examples include disputes over the Nile River between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia; tensions over the Indus River between India and Pakistan; and disagreements over the Tigris-Euphrates River system among Turkey, Syria, and Iraq.

Hydro political issues can be resolved through diplomatic negotiations, international treaties, joint management institutions, and equitable water-sharing agreements that balance the needs of all stakeholders.