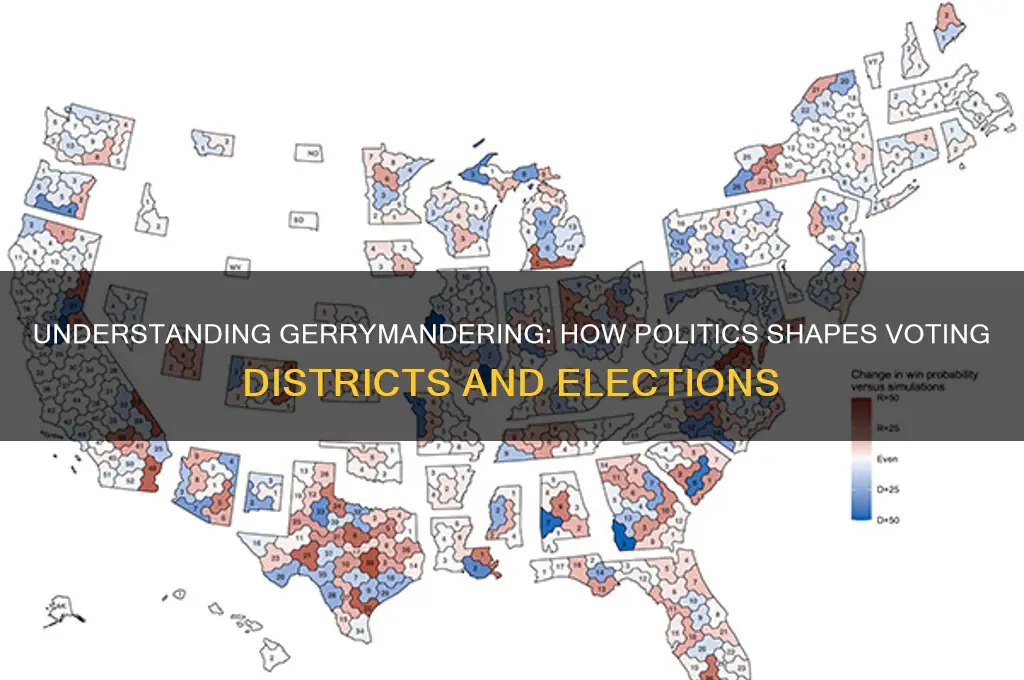

Gerrymandering is a controversial political tactic that involves manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts to favor one party or group over another. This practice often results in oddly shaped districts designed to dilute the voting power of opposition supporters or concentrate them in a few areas, thereby maximizing the number of seats won by the party in control of the redistricting process. While gerrymandering can be used to achieve various political goals, it is widely criticized for undermining democratic principles, distorting representation, and exacerbating political polarization. Understanding gerrymandering is crucial for grasping how electoral systems can be manipulated and the broader implications for fair and equitable political representation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The practice of drawing electoral district boundaries to favor one party or class, often resulting in distorted representation. |

| Purpose | To consolidate power by manipulating voting maps to dilute opposition votes or concentrate them in fewer districts. |

| Methods | - Cracking: Splitting opposition voters across multiple districts to reduce their impact. - Packing: Concentrating opposition voters into a single district to minimize their influence elsewhere. - Kidnapping: Shifting voters into districts where they are less likely to affect election outcomes. |

| Legal Status | Legal in the U.S. but subject to challenges under the 14th Amendment (Equal Protection Clause) and the Voting Rights Act. |

| Impact on Democracy | Undermines fair representation, reduces competitive elections, and diminishes voter trust in the electoral process. |

| Examples | - North Carolina (2010s): Republican-led redistricting led to heavily skewed congressional maps favoring GOP candidates. - Maryland (2020s): Democratic-led gerrymandering created districts favoring Democratic candidates. |

| Countermeasures | - Independent redistricting commissions. - Court-ordered redistricting. - Use of algorithmic tools for fairer map-drawing. |

| Recent Developments | Supreme Court rulings (e.g., Rucho v. Common Cause, 2019) stated federal courts cannot intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases, leaving it to state legislatures or voters. |

| Global Prevalence | Common in countries with winner-takes-all electoral systems, though less prevalent in proportional representation systems. |

| Public Opinion | Widely criticized by voters across the political spectrum, with polls showing strong support for reforms to end gerrymandering. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Gerrymandering means manipulating district boundaries to favor a political party or group

- Types of Gerrymandering: Includes cracking, packing, and stacking to dilute or concentrate votes

- Legal and Ethical Issues: Courts debate if gerrymandering violates constitutional rights or fair representation

- Impact on Elections: Distorted maps can skew election outcomes and reduce competitive races

- Reforms and Solutions: Proposals include independent commissions and algorithmic redistricting to ensure fairness

Definition and Origins: Gerrymandering means manipulating district boundaries to favor a political party or group

Gerrymandering, at its core, is the strategic redrawing of electoral district boundaries to favor one political party or group over another. This practice, often criticized for undermining democratic principles, involves reshaping districts to dilute the voting power of opponents or concentrate supporters in specific areas. The term itself dates back to 1812, when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry signed a bill that created a district resembling a salamander, sparking the portmanteau "Gerry-mander." This historical example highlights how gerrymandering has long been a tool for political manipulation, though its methods and impacts have evolved over time.

To understand gerrymandering, consider it as a cartographic puzzle where the pieces are rearranged not for geographic logic but for political gain. For instance, "cracking" involves spreading voters of the opposing party across multiple districts to reduce their influence, while "packing" concentrates them into a single district to limit their ability to win elsewhere. These techniques are not merely theoretical; they have been employed in states like North Carolina and Maryland, where courts have struck down maps as unconstitutional. The precision of modern gerrymandering is aided by advanced data analytics and mapping software, allowing parties to predict voter behavior with remarkable accuracy.

The origins of gerrymandering reflect its enduring nature as a political strategy. Early American politicians, including those in the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, used it to secure power in a fledgling nation. However, its modern incarnation is far more sophisticated, often involving extensive demographic and voting data to maximize partisan advantage. This evolution underscores a critical tension: while redistricting is a necessary process to account for population changes, gerrymandering exploits it to subvert the principle of "one person, one vote."

Combating gerrymandering requires both legal and procedural reforms. Courts have increasingly scrutinized redistricting efforts, with the Supreme Court ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019) that federal courts cannot address partisan gerrymandering claims, leaving the issue to state legislatures and voters. In response, states like California and Michigan have established independent redistricting commissions to reduce partisan influence. These commissions, composed of citizens rather than politicians, aim to create fairer maps by prioritizing community integrity and geographic continuity over political advantage.

Ultimately, gerrymandering is a symptom of deeper issues in electoral systems, including the winner-take-all approach to representation. Addressing it demands not only vigilance but also structural changes that prioritize fairness over partisanship. By understanding its definition, historical roots, and modern manifestations, voters and policymakers can work toward a more equitable democratic process. The fight against gerrymandering is not just about redrawing lines—it’s about redrawing the boundaries of political integrity.

Gautam Gambhir's Political Exit: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Types of Gerrymandering: Includes cracking, packing, and stacking to dilute or concentrate votes

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, employs several tactics to dilute or concentrate votes. Among these, cracking, packing, and stacking stand out as the most common methods. Each technique serves a distinct purpose, often used in combination to maximize the desired outcome. Understanding these strategies is crucial for recognizing how they distort democratic representation.

Cracking involves splitting a concentrated group of voters—often those who oppose the party in power—across multiple districts. By diluting their influence, this method ensures they become the minority in each district, effectively neutralizing their voting power. For example, if a city has a strong Democratic base, cracking might divide it into several Republican-leaning districts, rendering Democratic votes ineffective. This tactic is particularly effective in areas with geographically compact opposition populations, as it prevents them from winning any single district.

In contrast, packing consolidates opposition voters into a single district, often creating a lopsided victory for the opposing party while minimizing their impact elsewhere. This approach sacrifices one district to secure victories in surrounding areas. For instance, if a state has a significant Republican minority, packing might cluster them into one district, allowing Democrats to dominate the remaining districts. While the packed district may elect a Republican by a large margin, the overall effect is a net gain for Democrats in the state legislature.

Stacking, a less commonly discussed but equally potent tactic, involves pairing districts with vastly different population sizes or demographic compositions to favor the party in power. This method often exploits legal requirements for equal population distribution by overloading one district with opposition voters while spreading their allies thinly across others. For example, a rural, conservative-leaning district might be paired with an urban, liberal-leaning district, ensuring the conservative vote is diluted in the larger, more populous area.

To combat these practices, voters and advocates must remain vigilant. Analyzing district maps for irregular shapes or sudden demographic shifts can reveal gerrymandering attempts. Legal challenges, such as those based on the Voting Rights Act or constitutional principles of equal representation, have also proven effective in overturning manipulated districts. Additionally, independent redistricting commissions offer a structural solution by removing the process from partisan hands. By understanding these tactics and their implications, citizens can better advocate for fair electoral systems that reflect the true will of the electorate.

Mastering Corporate Politics: Strategies for Navigating Workplace Dynamics Effectively

You may want to see also

Legal and Ethical Issues: Courts debate if gerrymandering violates constitutional rights or fair representation

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party or group, has long sparked legal and ethical debates. At the heart of these debates is the question: Does gerrymandering violate constitutional rights or undermine fair representation? Courts have grappled with this issue, balancing the need for electoral integrity against the complexities of political power dynamics. The U.S. Supreme Court, in particular, has issued landmark rulings that shape how gerrymandering is legally assessed, though the issue remains contentious.

One key legal challenge lies in determining when gerrymandering crosses the line from strategic politics to unconstitutional manipulation. In *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), the Supreme Court addressed partisan gerrymandering but punted on establishing a clear standard for when it violates the Constitution. The Court’s reluctance to intervene stems from the difficulty of distinguishing between legitimate political advantage and unconstitutional discrimination. Critics argue that without a clear metric, gerrymandering will continue to distort representation, diluting the voting power of marginalized groups. Proponents, however, contend that redistricting is inherently political and should remain within the purview of state legislatures.

Ethically, gerrymandering raises concerns about fairness and equality in democratic systems. By packing opposition voters into a few districts or cracking them across many, gerrymandering can silence minority voices and entrench political majorities. For example, in North Carolina, courts struck down maps in 2019 for racially gerrymandering districts to dilute African American voting power. Such cases highlight the ethical dilemma: Should courts intervene to protect fair representation, or does doing so overstep their role in political processes? The tension between judicial activism and restraint is a recurring theme in these debates.

Practical solutions have emerged, such as independent redistricting commissions, which aim to remove partisan bias from the process. States like California and Arizona have adopted these commissions with mixed results. While they reduce overt gerrymandering, they are not immune to criticism, as political influence can still seep into their work. Courts must weigh these alternatives against the constitutional mandate for fair representation, ensuring that remedies do not create new inequities.

Ultimately, the debate over gerrymandering’s legality and ethics reflects broader questions about democracy and power. Courts must navigate the fine line between protecting constitutional rights and respecting political autonomy. As redistricting battles continue, the challenge remains: How can we ensure that electoral maps serve the people, not just the party in power? The answer may lie in a combination of judicial oversight, legislative reform, and public vigilance.

Navigating Political Conversations: Tips for Respectful and Productive Discussions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on Elections: Distorted maps can skew election outcomes and reduce competitive races

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has a profound and often insidious impact on election outcomes. By strategically clustering or dispersing voters, those in power can effectively predetermine results, turning what should be competitive races into foregone conclusions. For instance, in North Carolina’s 2018 midterm elections, Republicans won 50.3% of the statewide vote but secured 77% of the congressional seats due to gerrymandered maps. This distortion undermines the principle of "one person, one vote" and erodes public trust in the democratic process.

Consider the mechanics of how distorted maps achieve this skew. In a process known as "cracking," opposition voters are spread thinly across multiple districts, diluting their collective influence. Conversely, "packing" concentrates like-minded voters into a single district, wasting excess votes that could otherwise sway nearby races. These tactics not only favor the party in control but also discourage voter turnout. Why participate, voters may reason, if the outcome is already decided? A 2020 study by the Brennan Center found that gerrymandered districts saw turnout rates 2-3% lower than in competitive ones, a significant margin in close elections.

The reduction in competitive races is perhaps the most visible consequence of gerrymandering. In 2022, only 38 of the 435 U.S. House races were considered truly competitive, according to the Cook Political Report. This lack of competition discourages candidates from running, limits voter choice, and stifles political accountability. Incumbents in safe districts often prioritize partisan agendas over constituent needs, knowing their reelection is all but assured. For example, in Illinois’s heavily gerrymandered 4th district, the Democratic candidate has won by an average margin of 60% since 2012, leaving little incentive to address local issues or engage with voters.

To combat these effects, some states have adopted independent redistricting commissions. California’s Citizens Redistricting Commission, established in 2010, has produced maps that reflect population diversity and encourage competitive races. In 2022, 10 of the state’s 52 congressional districts were considered toss-ups, a stark contrast to states with partisan-controlled redistricting. However, such reforms are not without challenges. In Ohio, despite voters approving a bipartisan redistricting process in 2018, lawmakers have repeatedly ignored the rules, highlighting the need for robust enforcement mechanisms.

Ultimately, the impact of gerrymandering on elections is a call to action for voters, lawmakers, and advocates alike. By understanding how distorted maps skew outcomes and reduce competition, citizens can push for transparency, accountability, and fairer practices. Practical steps include supporting independent redistricting initiatives, using data tools like Dave’s Redistricting App to visualize map proposals, and holding elected officials accountable for their role in the process. The health of democracy depends on it—one district, one vote at a time.

Exploring Political Dance: Movements, Messages, and Social Change

You may want to see also

Reforms and Solutions: Proposals include independent commissions and algorithmic redistricting to ensure fairness

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, undermines democratic principles by distorting representation. To combat this, reformers propose two primary solutions: independent commissions and algorithmic redistricting. Each approach aims to remove partisan influence and ensure fairness, but they differ in methodology and potential outcomes.

Independent commissions, composed of non-partisan or bipartisan members, are tasked with redrawing district lines. States like California and Arizona have implemented such bodies, which typically include citizens, retired judges, or other neutral parties. These commissions operate under strict guidelines to prioritize criteria like population equality, contiguity, and respect for communities of interest. For instance, California’s commission holds public hearings and accepts input from citizens, fostering transparency. However, the success of these commissions hinges on rigorous selection processes to prevent partisan infiltration. Critics argue that even "independent" members may harbor biases, but empirical evidence suggests these commissions produce more competitive and representative districts compared to legislator-led efforts.

Algorithmic redistricting leverages technology to create impartial maps. By inputting objective criteria—such as population density, geographic compactness, and adherence to the Voting Rights Act—algorithms generate thousands of potential maps, from which the fairest can be selected. For example, the Public Mapping Project’s DistrictBuilder tool allows users to create and compare maps, ensuring transparency and accountability. Algorithmic approaches eliminate human bias, but they are not without challenges. The choice of criteria and data sources can still influence outcomes, and the complexity of algorithms may limit public understanding. Nonetheless, when paired with public oversight, these tools can serve as a powerful check against gerrymandering.

Combining both approaches—independent commissions and algorithmic tools—offers a robust solution. Commissions can use algorithms as a starting point, ensuring maps are mathematically fair, while also incorporating local knowledge and public input. This hybrid model has been proposed in states like Virginia, where lawmakers sought to balance technological precision with human judgment. However, implementation requires careful design: commissions must be truly independent, algorithms must be open-source and auditable, and the public must have meaningful opportunities to engage.

In practice, adopting these reforms demands political will and public pressure. Advocates should push for legislation that mandates independent commissions, funds algorithmic tools, and establishes clear fairness criteria. For instance, requiring districts to minimize population deviation and maximize compactness can codify fairness. Additionally, educating voters about gerrymandering’s impact and the benefits of reform can build momentum for change. While no solution is foolproof, independent commissions and algorithmic redistricting represent significant strides toward ensuring elections reflect the will of the people, not the whims of politicians.

Mastering Political Jiu Jitsu: Strategies for Turning Conflict into Control

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gerrymandering is the practice of manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts to favor one political party or group over another, often by concentrating or diluting the voting power of specific demographics.

Gerrymandering can distort election outcomes by creating "safe" districts for one party or packing opposition voters into fewer districts, reducing their overall representation and influencing legislative control.

While gerrymandering is not explicitly illegal, it is subject to legal challenges if it violates constitutional principles, such as the Equal Protection Clause, or if it discriminates based on race, as prohibited by the Voting Rights Act.

Gerrymandering can be mitigated through independent or nonpartisan redistricting commissions, transparent redistricting processes, and legal reforms that establish clear, impartial criteria for drawing district boundaries.