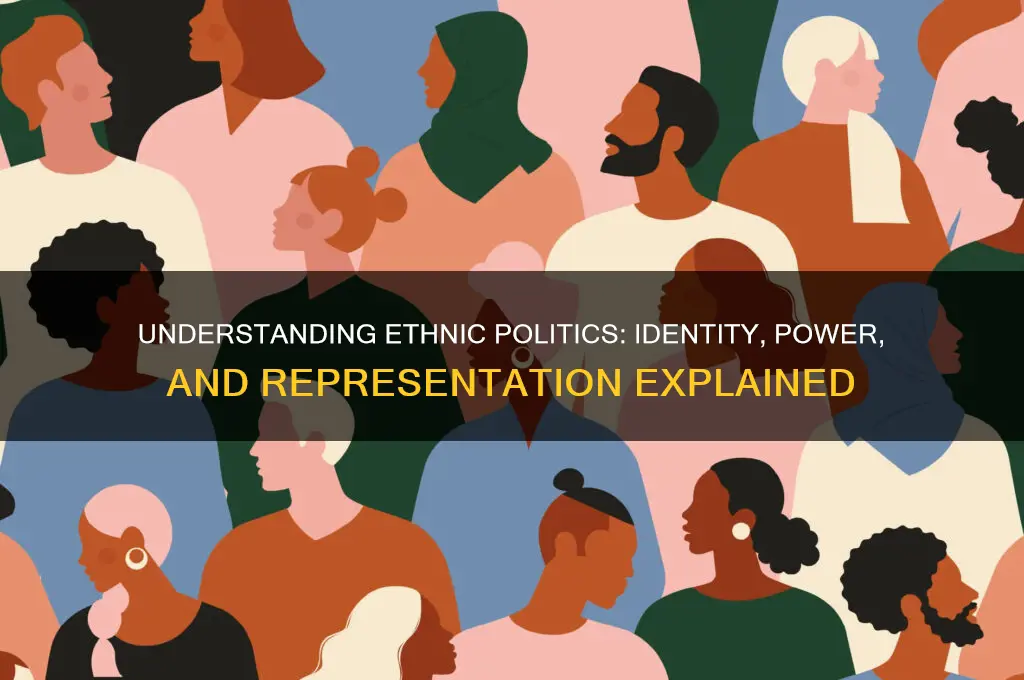

Ethnic politics refers to the ways in which ethnicity influences political behavior, institutions, and outcomes. It involves the mobilization of ethnic identities to achieve political goals, often through the formation of ethnic-based parties, interest groups, or movements. In ethnically diverse societies, politics can become deeply intertwined with cultural, linguistic, and religious differences, leading to both cooperation and conflict. Ethnic politics can shape policy-making, resource allocation, and power dynamics, sometimes fostering inclusivity and representation but also risking division, marginalization, and even violence. Understanding ethnic politics is crucial for addressing issues of identity, equality, and governance in multicultural societies.

Explore related products

$10.63 $21.99

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Scope: Understanding ethnic politics as identity-based mobilization in political systems

- Historical Roots: Tracing origins of ethnic politics in colonialism, nationalism, and state formation

- Key Theories: Exploring primordialism, instrumentalism, and constructivism in ethnic political studies

- Case Studies: Analyzing ethnic politics in diverse regions like Africa, Asia, and Europe

- Impacts and Challenges: Examining consequences of ethnic politics on democracy, conflict, and governance

Definition and Scope: Understanding ethnic politics as identity-based mobilization in political systems

Ethnic politics revolves around the mobilization of groups based on shared cultural, linguistic, religious, or racial identities within political systems. This phenomenon is not merely about representation but about how identities shape political behavior, policy-making, and power dynamics. For instance, in countries like India, Nigeria, and Belgium, ethnic identities often dictate voting patterns, party affiliations, and even government formation. Understanding ethnic politics requires dissecting how these identities are constructed, leveraged, and contested in the political arena.

To grasp the scope of ethnic politics, consider it as a lens through which political systems are analyzed. It involves examining how ethnic groups organize to secure resources, recognition, or autonomy. For example, the Kurdish movement in the Middle East or the Indigenous rights movements in Latin America illustrate how marginalized groups use political mobilization to challenge dominant structures. The scope extends beyond national borders, as diaspora communities often influence homeland politics, as seen in the Armenian or Jewish diasporas. This transnational dimension complicates traditional understandings of political boundaries.

A critical aspect of ethnic politics is its dual potential for both conflict and cooperation. On one hand, identity-based mobilization can exacerbate divisions, leading to ethnic violence or secessionist movements, as witnessed in Rwanda or the former Yugoslavia. On the other hand, it can foster solidarity and collective action, driving progressive policies or social justice initiatives. For instance, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States was fundamentally an ethnic political movement that reshaped national discourse and legislation. Balancing these outcomes requires nuanced strategies that acknowledge the legitimacy of ethnic claims while promoting inclusive governance.

Practical engagement with ethnic politics demands a multi-faceted approach. Policymakers must recognize the historical grievances and aspirations of ethnic groups, incorporating them into institutional frameworks. For example, power-sharing agreements in countries like South Africa or Northern Ireland have been instrumental in managing ethnic tensions. Civil society organizations play a crucial role in amplifying marginalized voices and fostering inter-ethnic dialogue. Individuals can contribute by challenging stereotypes and advocating for policies that address systemic inequalities. Ultimately, understanding ethnic politics as identity-based mobilization is essential for building equitable and resilient political systems.

Netanyahu's Political Future: Is His Career Truly Over?

You may want to see also

Historical Roots: Tracing origins of ethnic politics in colonialism, nationalism, and state formation

Ethnic politics, often understood as the mobilization of political identities based on shared cultural, linguistic, or religious traits, finds its roots deeply embedded in the processes of colonialism, nationalism, and state formation. Colonialism, by its very nature, disrupted traditional social structures and imposed artificial boundaries that grouped diverse communities together or separated those with shared identities. This reconfiguration of societies laid the groundwork for ethnic divisions, as colonial powers often employed a "divide and rule" strategy, exacerbating differences and fostering competition among groups. For instance, British colonial policies in Africa and India categorized populations into distinct ethnic or tribal units, creating identities that had not previously been politically salient.

Nationalism, emerging as a potent force in the 19th and 20th centuries, further entrenched ethnic politics by linking political legitimacy to cultural homogeneity. The rise of nation-states often excluded or marginalized groups that did not fit the dominant cultural narrative, leading to the politicization of ethnicity. In Eastern Europe, for example, the redrawing of borders after World War I created states like Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, where multiethnic populations were forced into uneasy coexistence. The aspiration for self-determination among these groups frequently manifested as ethnic nationalism, culminating in conflicts that persist to this day.

State formation itself played a critical role in institutionalizing ethnic politics. Postcolonial states, inheriting arbitrary colonial borders, struggled to forge national identities that transcended ethnic divisions. In many cases, dominant ethnic groups monopolized state power, alienating minorities and fueling grievances. Nigeria’s post-independence history illustrates this dynamic, where competition for resources and political representation along ethnic lines has repeatedly led to instability. Similarly, in Rwanda, colonial-era distinctions between Hutus and Tutsis were codified into identity cards, setting the stage for the 1994 genocide.

To trace the origins of ethnic politics is to recognize how these historical processes intersected to create enduring legacies. Colonialism sowed the seeds of division, nationalism amplified them, and state formation often failed to address the resulting inequalities. Understanding this history is crucial for addressing contemporary ethnic conflicts, as it highlights the need for inclusive political institutions and policies that recognize and respect diversity. Practical steps include implementing power-sharing agreements, promoting multicultural education, and fostering dialogue across ethnic divides. By acknowledging these historical roots, societies can work toward dismantling the structures that perpetuate ethnic politics and build more equitable futures.

Mastering Civil Political Conversations: Tips for Respectful Dialogue and Understanding

You may want to see also

Key Theories: Exploring primordialism, instrumentalism, and constructivism in ethnic political studies

Ethnic politics, at its core, revolves around the role of ethnicity in shaping political identities, mobilization, and conflict. To understand its dynamics, scholars have developed key theories: primordialism, instrumentalism, and constructivism. Each offers distinct insights into how ethnicity influences political behavior, though they often clash in their explanations.

Primordialism posits that ethnic identities are innate, deeply rooted in shared ancestry, culture, or history. This theory treats ethnicity as a fixed, unchanging force that naturally drives political allegiances. For instance, in Rwanda, Hutu and Tutsi identities, though socially constructed over time, were framed as primordial during the 1994 genocide, fueling extreme violence. Critics argue that primordialism oversimplifies complex social realities, ignoring how identities can be manipulated or redefined. Yet, its strength lies in explaining why certain ethnic divisions persist across generations, often resisting external interventions.

Instrumentalism, in contrast, views ethnicity as a tool wielded by elites to achieve political goals. Here, ethnic identities are not inherent but strategically mobilized to rally support, consolidate power, or divert attention from other issues. A classic example is Kenya’s post-colonial politics, where leaders like Jomo Kenyatta exploited ethnic loyalties to secure dominance. Instrumentalism highlights the fluidity of ethnic identities, showing how they can be amplified or downplayed depending on political expediency. However, it risks underestimating the emotional and cultural weight ethnicity holds for individuals, reducing it to mere manipulation.

Constructivism bridges the gap between these extremes, arguing that ethnic identities are socially constructed through interactions, narratives, and institutions. This theory emphasizes how ethnicity is shaped and reshaped by historical, political, and economic contexts. For instance, the rise of Kurdish nationalism in Iraq and Turkey reflects a constructed identity forged through shared struggles and external oppression. Constructivism offers a nuanced view, acknowledging both the durability and adaptability of ethnic identities. It challenges scholars to examine the processes—such as education, media, or state policies—that construct and reconstruct ethnicity over time.

When applying these theories, consider their implications for policy and practice. Primordialism might suggest that ethnic conflicts are inevitable, requiring external mediation. Instrumentalism could inform strategies to de-escalate tensions by addressing elite manipulation. Constructivism encourages long-term solutions, such as inclusive education or institutional reforms, to reshape ethnic narratives. Each theory provides a lens, but their combination offers a richer understanding of ethnic politics, enabling more effective interventions in diverse contexts.

Understanding Political Fronts: Definitions, Roles, and Global Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Case Studies: Analyzing ethnic politics in diverse regions like Africa, Asia, and Europe

Ethnic politics, the mobilization of political identities based on shared cultural, linguistic, or religious affiliations, manifests differently across regions, shaped by historical contexts, colonial legacies, and socioeconomic factors. In Africa, Asia, and Europe, case studies reveal distinct patterns and consequences of ethnic politics, offering insights into both its challenges and potential for cohesion.

Consider Rwanda, where ethnic politics culminated in the 1994 genocide. Colonial-era policies institutionalized ethnic divisions between Hutus and Tutsis, creating a hierarchy that fueled resentment and competition for resources. Post-genocide, Rwanda’s government has implemented policies to de-emphasize ethnic identities, promoting a unified "Rwandan" identity. This case underscores how externally imposed ethnic categorizations can escalate into violence and the importance of inclusive governance in mitigating conflict. For practitioners, Rwanda illustrates the need to address historical grievances and foster shared national narratives to prevent ethnic tensions from boiling over.

In contrast, India’s ethnic politics is characterized by a complex interplay of caste, religion, and regional identities within a democratic framework. The reservation system, which allocates quotas for marginalized castes in education and employment, aims to redress historical inequalities but has also sparked debates over meritocracy and social justice. India’s case highlights the dual-edged nature of affirmative action policies: while they can empower underrepresented groups, they may also deepen divisions if not accompanied by broader economic and social reforms. Policymakers can learn from India’s experience by balancing targeted interventions with inclusive development strategies to avoid exacerbating ethnic cleavages.

Europe’s ethnic politics often revolves around migration and the integration of minority groups, as seen in the case of the Roma in Eastern Europe. Despite being Europe’s largest ethnic minority, the Roma face systemic discrimination, segregation, and political marginalization. Initiatives like the EU’s Roma Strategic Framework aim to improve their socioeconomic conditions, but progress remains slow due to entrenched biases and inadequate implementation. This case study emphasizes the need for multi-level interventions—combining legal protections, community engagement, and public awareness campaigns—to combat ethnic exclusion. For advocates, the Roma’s situation serves as a reminder that policy frameworks alone are insufficient without addressing societal attitudes and ensuring local buy-in.

Finally, Belgium’s linguistic divide between Flanders and Wallonia offers a unique perspective on ethnic politics in a developed nation. The country’s federal structure, designed to accommodate Dutch-speaking Flemings and French-speaking Walloons, has become a source of political gridlock and regional competition. While Belgium has avoided violence, its case demonstrates how ethnic-linguistic identities can hinder national unity and governance. For analysts, Belgium’s experience suggests that power-sharing arrangements, while necessary, must be complemented by mechanisms to foster cross-community cooperation and shared goals.

These case studies reveal that ethnic politics is not inherently destabilizing but is shaped by how societies manage diversity. Practitioners and policymakers can draw actionable lessons: address historical injustices, design inclusive policies, combat discrimination at all levels, and promote cross-cutting identities. By studying these diverse regions, we gain a toolkit for navigating the complexities of ethnic politics and building more cohesive societies.

Mastering Political Document Analysis: Strategies for Insightful Interpretation

You may want to see also

Impacts and Challenges: Examining consequences of ethnic politics on democracy, conflict, and governance

Ethnic politics, characterized by the mobilization of political identities based on ethnicity, has profound and multifaceted impacts on democracy, conflict, and governance. One of its most immediate consequences is the polarization of societies. When political parties or leaders exploit ethnic divisions for electoral gain, they often deepen social fractures, making it harder for citizens to unite around shared national goals. For instance, in countries like Kenya and Nigeria, ethnic-based political campaigns have historically fueled mistrust and violence, undermining the very fabric of democratic coexistence. This polarization not only weakens social cohesion but also distorts democratic processes, as voters are swayed by identity rather than policy.

The erosion of democratic institutions is another critical challenge posed by ethnic politics. In systems where ethnicity dominates political discourse, institutions like the judiciary, civil service, and electoral bodies often become tools for advancing ethnic interests rather than upholding the rule of law. This politicization of institutions leads to their inefficiency and loss of legitimacy. For example, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the ethnic-based power-sharing system enshrined in the Dayton Accords has resulted in gridlock and corruption, hindering effective governance and economic development. Such outcomes highlight how ethnic politics can subvert the principles of democracy, replacing meritocracy with patronage and favoritism.

Conflict is perhaps the most visible and devastating consequence of ethnic politics. When political identities are tightly bound to ethnicity, disputes over resources, power, or representation can escalate into violence. The Rwandan genocide of 1994 stands as a stark reminder of how ethnic politics, when weaponized, can lead to catastrophic human rights violations. Even in less extreme cases, ethnic tensions can simmer beneath the surface, erupting periodically into clashes that destabilize regions. For instance, the ongoing ethnic conflicts in Ethiopia’s Tigray region demonstrate how political manipulation of ethnic identities can trigger prolonged humanitarian crises, displacing millions and straining international relations.

Despite these challenges, ethnic politics is not inherently destructive. In some contexts, it can serve as a mechanism for marginalized groups to assert their rights and gain political representation. Indigenous movements in Latin America, such as those in Bolivia and Ecuador, have used ethnic politics to challenge historical exclusion and promote policies that benefit their communities. However, this approach requires careful management to avoid exacerbating divisions. Policymakers must strike a balance between recognizing ethnic diversity and fostering inclusive national identities, ensuring that political systems do not become captive to identity-based interests.

To mitigate the negative impacts of ethnic politics, governments and international organizations must adopt proactive strategies. First, electoral systems should be redesigned to incentivize cross-ethnic coalitions rather than reward ethnic bloc voting. Second, education systems must promote multicultural understanding and civic values to counteract divisive narratives. Third, independent media and civil society organizations play a crucial role in holding leaders accountable and amplifying voices that advocate for unity. By addressing the root causes of ethnic polarization and strengthening democratic institutions, societies can navigate the complexities of ethnic politics while safeguarding peace and governance.

Navigating Turmoil: Understanding Political Crisis Management Strategies and Solutions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ethnic politics refers to the use of ethnicity as a basis for political mobilization, identity formation, and policy-making. It involves the organization of political interests and actions around shared cultural, linguistic, religious, or ancestral affiliations.

Ethnic politics often shapes voting patterns, as individuals may vote along ethnic lines to support candidates or parties perceived to represent their group’s interests. This can lead to the formation of ethnic blocs or coalitions in electoral processes.

Ethnic politics can exacerbate divisions, fuel conflict, and marginalize minority groups. It may also lead to the prioritization of ethnic interests over national unity, undermining inclusive governance and social cohesion.

Yes, when managed constructively, ethnic politics can promote cultural preservation, representation of diverse groups, and the addressing of specific community needs. It can also foster pluralism and inclusivity in democratic systems.

While both involve group identity, ethnic politics focuses on specific ethnic or cultural groups within a society, whereas nationalism emphasizes a broader, often state-based identity. Ethnic politics can be a subset of nationalism but is more narrowly focused on particular communities.