Anthony Downs' definition of a political party is a pivotal concept in political science, offering a strategic and goal-oriented perspective. In his seminal work, *An Economic Theory of Democracy*, Downs defines a political party as a team of individuals who seek to win elections in order to control government power and implement their preferred policies. According to Downs, parties are rational actors that aim to maximize their electoral support by appealing to the median voter, adapting their platforms to reflect the preferences of the majority. This definition emphasizes the competitive nature of party politics, where parties act as instruments for achieving and maintaining power rather than merely representing fixed ideologies or interests. Downs' framework highlights the dynamic and adaptive behavior of political parties in democratic systems, making it a cornerstone for understanding party strategy and voter behavior.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Team of Men | A political party is a group of individuals working together. |

| Seeks to Control Government | The primary goal is to gain and maintain political power. |

| Influences Policy/Legislation | Aims to shape public policy and laws in line with its ideology. |

| Responsive to Public Preferences | Adapts policies to reflect the preferences of the electorate. |

| Seeks Votes in Elections | Competes in elections to secure voter support. |

| Rational and Goal-Oriented | Acts strategically to maximize its chances of winning power. |

| Ideological or Pragmatic | May be driven by ideology, pragmatism, or a combination of both. |

| Organized Structure | Has a formal or informal hierarchy to coordinate activities. |

| Mobilizes Supporters | Engages and activates its base to achieve political objectives. |

| Competes in the Political Market | Operates within a competitive environment with other parties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Downs' Economic Theory: Parties as competing brands maximizing votes via policy differentiation in a market-like system

- Policy Convergence: Parties converge toward median voter preferences to secure electoral majority

- Ideological Positioning: Parties strategically place themselves on ideological spectra to attract voter support

- Rational Voter Choice: Voters choose parties based on policy proximity, not loyalty or identity

- Party Competition: Downs emphasizes competition as the driver of party behavior and policy shifts

Downs' Economic Theory: Parties as competing brands maximizing votes via policy differentiation in a market-like system

Anthony Downs' economic theory of political parties reframes democracy as a marketplace of ideas, where parties function as competing brands vying for consumer (voter) loyalty. This analogy, while provocative, offers a surprisingly insightful lens for understanding party behavior. Imagine the political spectrum as a supermarket aisle, with parties strategically positioning themselves as distinct products to capture the largest possible market share – in this case, votes.

Just as Coca-Cola and Pepsi differentiate themselves through taste, packaging, and marketing, Downs argues that political parties differentiate themselves through policy platforms. This differentiation is crucial. A party advocating for identical policies as its competitor would be redundant, leaving voters with no reason to choose one over the other.

Downs' theory hinges on the assumption of rationality – both on the part of parties and voters. Parties, acting as rational actors, will adjust their policy positions to maximize their vote share. This might involve shifting left or right on the political spectrum, adopting more populist rhetoric, or emphasizing specific issues that resonate with key demographics. Voters, also assumed to be rational, will choose the party whose policies most closely align with their own preferences.

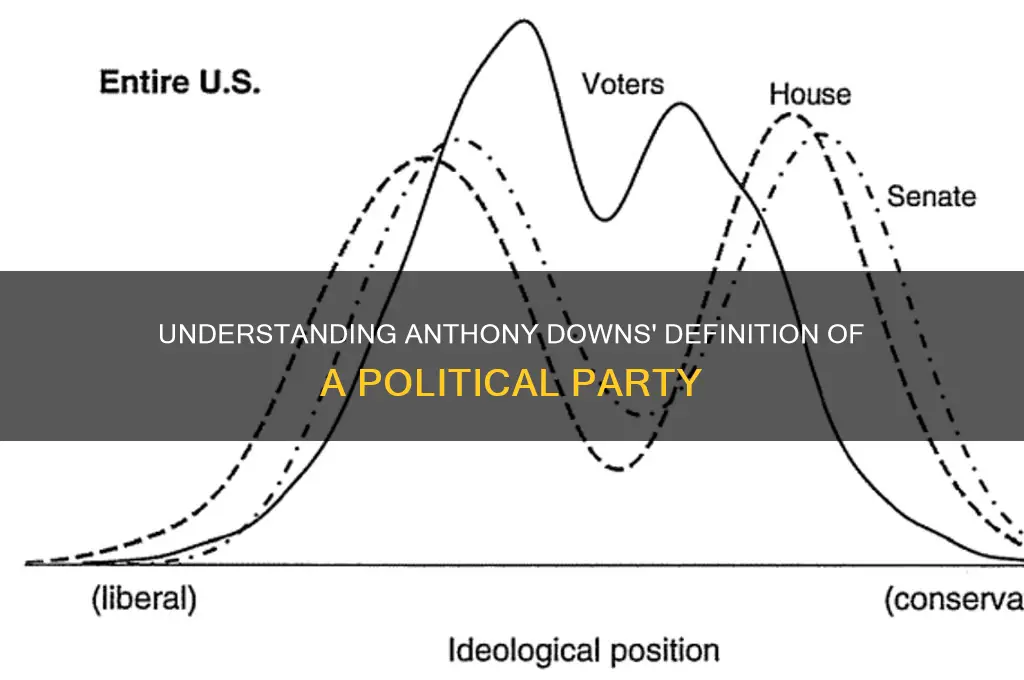

This market-like system, Downs argues, leads to a natural convergence towards the center. Parties, seeking to appeal to the largest number of voters, will gravitate towards the median voter – the individual whose preferences lie at the ideological center of the electorate. This explains why, in many democracies, major parties often appear to offer similar, centrist policies despite their ideological differences.

However, Downs' theory isn't without its limitations. It assumes a perfectly informed electorate, capable of accurately assessing and comparing party platforms. In reality, voter information is often incomplete or biased, leading to suboptimal choices. Additionally, the theory struggles to account for the influence of special interest groups, ideological purists, and the emotional factors that often drive voting behavior.

Despite these limitations, Downs' economic theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the strategic calculations that underpin party politics. It highlights the importance of policy differentiation, the role of voter preferences in shaping party platforms, and the inherent pressures that push parties towards the political center. By viewing parties as brands competing in a market for votes, we gain a more nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics that shape democratic systems.

Chief Justice Jorge Labarga's Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Policy Convergence: Parties converge toward median voter preferences to secure electoral majority

In the realm of political strategy, Anthony Downs' theory of policy convergence reveals a calculated dance between parties and the electorate. Imagine a political spectrum as a number line, with extreme positions at either end and the median voter sitting squarely in the middle. Downs argues that rational political parties, driven by the ultimate goal of winning elections, will gravitate towards this median voter's preferences. This isn't about ideological purity; it's about securing the most votes.

Think of it like a game of political capture the flag. The flag represents the majority, and parties adjust their positions to be closest to it. This strategic maneuvering often leads to a blurring of policy differences between major parties, as they both aim for the same target.

This convergence has tangible consequences. For instance, consider healthcare policy debates. A party advocating for universal healthcare might temper their initial proposal, opting for a public option instead, to appeal to voters wary of a complete overhaul. Conversely, a party initially opposed to any government involvement might soften their stance, proposing subsidies for private insurance to capture centrist voters. This tactical adjustment, while potentially frustrating for ideological purists, reflects the reality of Downs' theory in action.

The median voter theorem, a cornerstone of Downs' argument, suggests that parties ignore this centrist bloc at their peril. By focusing solely on their base, they risk alienating the very voters needed to secure victory. This dynamic encourages parties to adopt policies that, while not necessarily revolutionary, are palatable to the majority.

However, policy convergence isn't without its pitfalls. Critics argue that this focus on the median voter can lead to a lack of bold, transformative policies. If parties are constantly chasing the center, who advocates for the marginalized or pushes for systemic change? Furthermore, the assumption of a static median voter is questionable. Public opinion is fluid, influenced by events, media, and shifting societal norms. Parties must constantly recalibrate their positions, risking appearing inconsistent or inauthentic.

Despite these criticisms, Downs' theory remains a powerful lens through which to understand party behavior. It highlights the inherent tension between ideological purity and electoral success, reminding us that the political landscape is often shaped by strategic calculations rather than unwavering principles.

Understanding policy convergence empowers voters to see beyond campaign rhetoric and recognize the underlying motivations driving party platforms. It encourages a more nuanced understanding of the political process, where the pursuit of power often necessitates a pragmatic approach to policy formulation.

Andrew Jackson's Political Party: Unraveling the Democratic Legacy

You may want to see also

Ideological Positioning: Parties strategically place themselves on ideological spectra to attract voter support

Political parties are not static entities; they are dynamic organizations that constantly adapt to the shifting sands of public opinion. Anthony Downs' definition of a political party highlights their role as rational actors seeking to maximize votes, and ideological positioning is a key strategy in this pursuit. This involves a calculated placement along various ideological spectra, such as left-right, liberal-conservative, or progressive-traditionalist, to appeal to specific voter demographics.

Consider the classic left-right spectrum. Parties on the left traditionally advocate for greater government intervention, social welfare programs, and progressive taxation, attracting voters concerned with social justice and equality. Conversely, right-leaning parties emphasize individual liberty, free markets, and limited government, resonating with voters prioritizing economic freedom and personal responsibility. This strategic positioning allows parties to carve out distinct niches, attracting voters who align with their core principles.

For instance, a party might position itself slightly left of center, advocating for moderate social welfare programs and a mixed economy, to appeal to both socially conscious voters and those wary of extreme government intervention. This nuanced positioning allows them to capture a broader swath of the electorate.

However, ideological positioning is not without its pitfalls. Parties risk alienating their core base if they shift too far from their traditional stance. For example, a traditionally conservative party adopting overly progressive policies might lose support from its loyal, right-leaning voters. Conversely, a party that remains rigidly adherent to its ideology may fail to attract new voters and become increasingly marginalized. Striking the right balance requires a deep understanding of the electorate's evolving preferences and a willingness to adapt without compromising core values.

A successful ideological positioning strategy involves continuous research and analysis of voter attitudes, demographics, and emerging issues. Parties must be agile, adjusting their messaging and policy proposals to reflect the changing political landscape. This dynamic approach ensures they remain relevant and competitive in the ever-shifting arena of electoral politics.

Jamaica's Election Strategies: How Political Parties Gear Up for Victory

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.79 $26.99

Rational Voter Choice: Voters choose parties based on policy proximity, not loyalty or identity

Anthony Downs' definition of a political party hinges on its role as a policy aggregator, a concept central to his "rational voter choice" theory. This theory posits that voters, acting as rational agents, select parties based on the proximity of their policy platforms to the voter's own ideological position. Imagine a political spectrum as a line, with voters positioned along it according to their beliefs. Parties, to maximize their appeal, cluster their policies around these voter positions, effectively minimizing the ideological distance between themselves and potential supporters.

This model challenges the notion that party loyalty or identity politics are the primary drivers of voter behavior. Downs argues that while these factors may influence some voters, the rational calculation of policy alignment ultimately prevails.

Consider a voter passionate about environmental protection. While they might identify as a Democrat, if a Republican candidate proposes a more comprehensive environmental policy package, Downs' theory suggests the voter would rationally choose the Republican, prioritizing policy proximity over party affiliation. This example highlights the dynamic nature of voter choice within Downs' framework. Parties, aware of this rationality, strategically adjust their platforms to capture the largest possible share of the electorate, leading to a convergence of policies towards the median voter's position.

This focus on policy proximity has significant implications for campaign strategies. Parties invest heavily in crafting and communicating policies that resonate with the median voter, often employing polling and focus groups to gauge public opinion. This can lead to a certain degree of policy homogenization, as parties strive to occupy the ideological center ground.

However, Downs' model is not without its limitations. It assumes a well-informed electorate capable of accurately assessing policy positions. In reality, information asymmetries and cognitive biases can distort voter perceptions. Additionally, the model struggles to account for the emotional and symbolic aspects of political identity, which can be powerful motivators.

Despite these limitations, Downs' theory of rational voter choice based on policy proximity remains a cornerstone of political science. It provides a valuable framework for understanding party competition and voter behavior, offering insights into the strategic calculations that underpin democratic elections.

Exploring the Czech Republic's Diverse Political Party Landscape

You may want to see also

Party Competition: Downs emphasizes competition as the driver of party behavior and policy shifts

Anthony Downs' definition of a political party hinges on its role as a vote-maximizing entity. In his seminal work, *An Economic Theory of Democracy*, Downs argues that parties are not primarily ideological crusaders but rational actors seeking electoral victory. This core principle underpins his emphasis on competition as the primary driver of party behavior and policy shifts.

In a competitive political landscape, parties constantly adjust their positions to attract the median voter, the individual whose preferences sit at the ideological center of the electorate. This strategic calculus leads to a dynamic where parties converge towards the political center, blurring ideological distinctions and prioritizing broad appeal over rigid dogma.

Consider the evolution of major parties in the United States. The Democratic Party, once dominated by Southern conservatives, has shifted significantly leftward on social issues like civil rights and LGBTQ+ rights to capture the growing progressive vote. Conversely, the Republican Party, traditionally associated with fiscal conservatism, has increasingly embraced populist rhetoric and protectionist policies to appeal to a different segment of the electorate. These shifts illustrate Downs' theory in action: parties adapt their platforms not out of ideological purity but to outmaneuver their competitors and secure electoral victory.

However, this focus on competition has its limitations. The pursuit of the median voter can lead to a homogenization of party platforms, leaving voters with limited genuine choices. Furthermore, the emphasis on short-term electoral gains can overshadow long-term policy solutions, as parties prioritize immediate vote-winning strategies over addressing complex, systemic issues.

Despite these criticisms, Downs' theory remains a powerful lens through which to understand party behavior. By recognizing the centrality of competition, we gain valuable insights into the strategic calculations that shape political landscapes. This understanding is crucial for voters seeking to navigate the complexities of modern democracies and for policymakers aiming to design electoral systems that foster genuine representation and meaningful policy debates.

Declaring a Political Party in Ohio: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Downs defines a political party as a team of men seeking to control the governing apparatus by gaining office in a duly constituted election.

Downs argues that the primary goal of political parties is to win elections and secure political power, rather than strictly adhering to ideological principles.

Downs emphasizes that political parties are primarily pragmatic, focusing on winning elections and appealing to the median voter, rather than being driven by rigid ideology.

In Downs' theory, political parties position themselves to appeal to the median voter, whose preferences determine the outcome of elections, leading parties to converge on centrist policies.

Downs' definition differs from traditional views by focusing on the strategic, election-oriented behavior of parties rather than their ideological or representational roles.