Détente politics refers to a period of relaxed tensions and improved relations between opposing nations, particularly during the Cold War era. Emerging in the late 1960s and early 1970s, détente marked a shift from confrontational policies to diplomatic engagement, primarily between the United States and the Soviet Union. This era was characterized by arms control agreements, such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), cultural exchanges, and economic cooperation, aimed at reducing the risk of nuclear conflict and fostering stability. While détente did not end ideological rivalry, it represented a pragmatic approach to managing global tensions and laid the groundwork for future diplomatic efforts in international relations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A period of relaxed tensions and improved relations between adversarial nations, particularly during the Cold War. |

| Key Period | 1969–1979, primarily between the United States and the Soviet Union. |

| Primary Goal | Reducing the risk of nuclear conflict and fostering cooperation. |

| Key Agreements | SALT I (1972), ABM Treaty (1972), Helsinki Accords (1975). |

| Economic Cooperation | Increased trade, technological exchanges, and cultural interactions. |

| Diplomatic Efforts | Frequent summits and negotiations between leaders (e.g., Nixon and Brezhnev). |

| Military De-escalation | Reduction in arms race, withdrawal of troops from conflict zones. |

| Cultural Exchanges | Joint artistic, scientific, and educational programs (e.g., Apollo-Soyuz mission). |

| Limitations | Did not end ideological rivalry; tensions resurfaced later (e.g., Afghanistan invasion in 1979). |

| Modern Relevance | Concepts of détente are applied in contemporary diplomacy to ease tensions (e.g., U.S.-China relations). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Détente: Cold War tensions ease, superpowers seek cooperation, reducing nuclear threat, fostering diplomatic relations

- Key Agreements: SALT I, ABM Treaty, Helsinki Accords, limiting arms, ensuring stability, promoting human rights

- Role of Leaders: Nixon, Kissinger, Brezhnev, Brandt, driving policies, personal diplomacy, shaping global dialogue

- Economic Factors: Trade, technology, energy, interdependence, mutual benefits, reducing conflict incentives, fostering peace

- Challenges & Limits: Ideological differences, regional conflicts, mistrust, détente fragile, eventual decline, Cold War resurgence

Origins of Détente: Cold War tensions ease, superpowers seek cooperation, reducing nuclear threat, fostering diplomatic relations

The Cold War's icy grip on global politics began to thaw in the 1960s and 1970s, giving rise to a period known as Détente. This era marked a significant shift from the previous decades of heightened tensions and brinkmanship between the United States and the Soviet Union. The origins of Détente can be traced back to a mutual recognition of the dangers posed by the nuclear arms race and a growing desire to prevent catastrophic conflict. As both superpowers sought to reduce the risk of nuclear annihilation, they embarked on a path of cautious cooperation, laying the groundwork for a new phase in international relations.

A Nuclear Catalyst for Change

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 served as a stark wake-up call, bringing the world to the brink of nuclear disaster. This crisis became a turning point, prompting both superpowers to reconsider their aggressive posturing. The realization that nuclear war could lead to mutual destruction sparked a pragmatic approach to diplomacy. In the aftermath, the United States and the Soviet Union took initial steps towards arms control, signing the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which prohibited nuclear testing in the atmosphere, outer space, and underwater. This treaty set a precedent for future agreements and demonstrated that cooperation was not only possible but essential for survival.

Diplomatic Overture and Strategic Interests

Détente was not merely a product of fear but also a result of calculated strategic interests. The Soviet Union, under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, sought to consolidate its influence in Eastern Europe and gain recognition for its post-World War II territorial gains. Meanwhile, the United States, facing challenges in Vietnam and a changing global landscape, recognized the need to engage with the Soviet Union to achieve stability. This convergence of interests led to a series of diplomatic initiatives. The Hotline Agreement of 1963 established a direct communication link between Washington and Moscow, reducing the risk of accidental war. Subsequently, the Glassboro Summit in 1967 and the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) in the early 1970s further solidified the détente process, resulting in agreements to limit strategic nuclear weapons.

A Complex Dance of Cooperation and Competition

The détente era was characterized by a delicate balance between cooperation and continued competition. While both superpowers engaged in arms control negotiations, they also sought to expand their influence in various regions. The United States, for instance, pursued a policy of triangulation, improving relations with China to counterbalance the Soviet Union. This period saw a complex interplay of diplomacy, with each superpower attempting to gain advantages while maintaining the overall stability of the détente framework. The Helsinki Accords of 1975, signed by 35 nations, including the US and the USSR, exemplified this dynamic. The agreement addressed security, economic, and human rights issues, fostering cooperation while also acknowledging the existing political divisions in Europe.

Legacy and Lessons

The origins of Détente offer valuable insights into the management of international conflicts. It demonstrates that even in the most hostile of environments, dialogue and cooperation can emerge from shared interests and the recognition of mutual vulnerabilities. The reduction of nuclear tensions during this period provided a breathing space, allowing for the exploration of diplomatic solutions. However, Détente also highlights the complexities of superpower relations, where cooperation and competition coexist. This era serves as a reminder that while diplomatic breakthroughs are possible, they require constant nurturing and a nuanced understanding of each party's interests and fears. The lessons from Détente continue to inform strategies for conflict resolution and arms control in the modern era, where global powers navigate an ever-evolving geopolitical landscape.

Religious Conflict's Political Roots: Power, Identity, and State Interests

You may want to see also

Key Agreements: SALT I, ABM Treaty, Helsinki Accords, limiting arms, ensuring stability, promoting human rights

The era of détente in the 1970s was marked by a series of pivotal agreements aimed at reducing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. Among these, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I), the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, and the Helsinki Accords stand out as cornerstones of this policy. Each agreement addressed critical aspects of Cold War rivalry, from nuclear arms control to human rights, laying the groundwork for a more stable international order.

SALT I, signed in 1972, was a landmark effort to curb the nuclear arms race. It froze the number of strategic ballistic missile launchers at existing levels, effectively capping the growth of nuclear arsenals. For instance, the treaty limited the U.S. and the Soviet Union to 2,360 and 2,400 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launchers, respectively. This agreement was not about disarmament but about preventing unchecked proliferation, ensuring neither side could gain a decisive advantage. The takeaway here is clear: by setting quantitative limits, SALT I introduced a measure of predictability into the arms race, reducing the risk of accidental escalation.

Complementing SALT I was the ABM Treaty, which restricted the deployment of anti-ballistic missile systems. Each side was allowed only two ABM sites, with a maximum of 100 interceptors each. This treaty was crucial because it preserved the doctrine of mutual assured destruction (MAD), the strategic balance that deterred nuclear war. Without limits on defensive systems, both superpowers might have felt compelled to expand their offensive capabilities, reigniting the arms race. The ABM Treaty thus served as a stabilizer, ensuring that neither side could undermine the other’s deterrent.

While SALT I and the ABM Treaty focused on military constraints, the Helsinki Accords of 1975 took a broader approach, linking security to human rights. Signed by 35 nations, including the U.S. and the Soviet Union, the accords recognized post-World War II borders and committed signatories to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms. This was a significant concession by the Soviet Union, which had long resisted external scrutiny of its internal affairs. Practically, the accords established mechanisms for monitoring compliance, such as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). While not legally binding, the Helsinki Accords provided a moral framework that empowered dissidents in the Eastern Bloc, contributing to the eventual collapse of Soviet control in Eastern Europe.

Together, these agreements illustrate the multifaceted nature of détente. By limiting arms, ensuring stability, and promoting human rights, they addressed both the symptoms and root causes of Cold War tensions. For instance, while SALT I and the ABM Treaty reduced the risk of nuclear conflict, the Helsinki Accords sowed the seeds of ideological change. This dual approach—combining hard security measures with soft diplomatic efforts—offers a model for managing great power rivalries today. The lesson is that stability requires more than just arms control; it demands a commitment to shared values and norms.

Understanding the Selection Process of Political Leaders Worldwide

You may want to see also

Role of Leaders: Nixon, Kissinger, Brezhnev, Brandt, driving policies, personal diplomacy, shaping global dialogue

The 1970s marked a seismic shift in Cold War dynamics, characterized by détente—a strategic easing of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. At the heart of this transformation were key leaders whose personal diplomacy and policy decisions reshaped global dialogue. Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, Leonid Brezhnev, and Willy Brandt emerged as architects of this era, leveraging their unique styles and visions to navigate the complexities of superpower rivalry. Their actions demonstrate how individual leadership can drive systemic change, even in the most entrenched geopolitical conflicts.

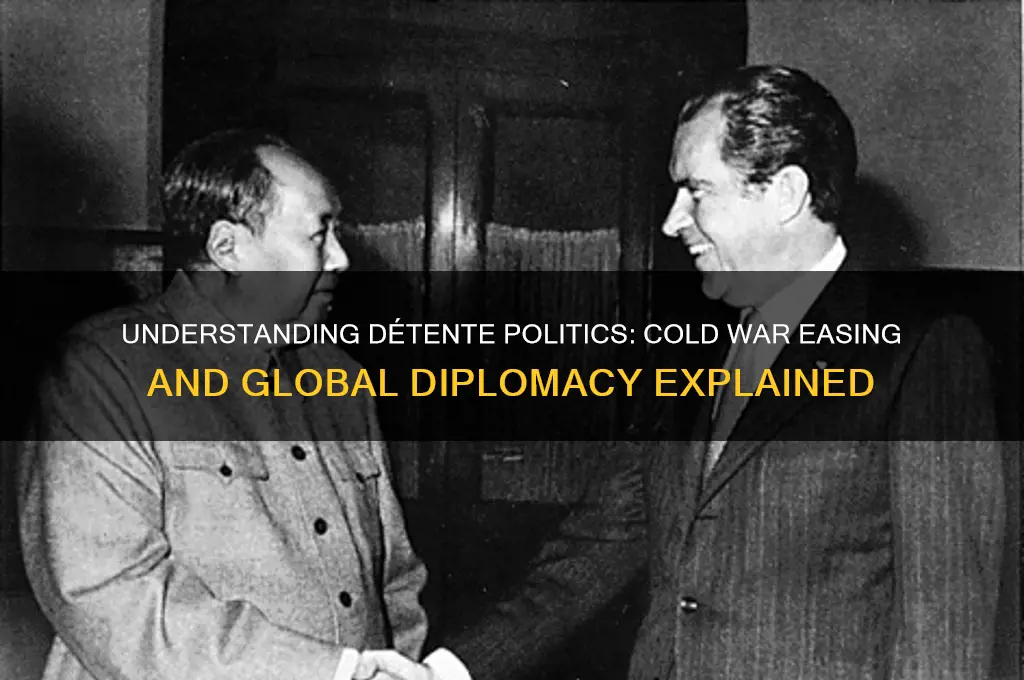

Nixon and Kissinger, operating as a tandem, pioneered a pragmatic approach to détente, rooted in realpolitik. Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, followed by his summit with Brezhnev in Moscow, exemplified their strategy of triangular diplomacy. By engaging both adversaries and allies, they sought to create a balance of power that reduced the risk of nuclear confrontation. Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy—a relentless back-and-forth between capitals—was instrumental in negotiating the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. These agreements, while limited in scope, symbolized a mutual recognition of the dangers of unchecked escalation. Their method was analytical, focusing on incremental gains rather than ideological victories.

Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, played a dual role in détente: as a cautious partner and a defender of Soviet interests. While he embraced agreements like SALT I, he also pursued policies that expanded Soviet influence, such as détente in Europe, which culminated in the Helsinki Accords of 1975. These accords, championed by West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, institutionalized détente by linking security to human rights and economic cooperation. Brandt’s Ostpolitik, a policy of rapprochement with East Germany and the Soviet bloc, was a bold gamble that paid dividends by reducing tensions in Europe. His approach was instructive, demonstrating how diplomacy could bridge ideological divides without compromising core values.

The personal chemistry between these leaders was as critical as their policies. Nixon and Brezhnev’s summitry, marked by toasts and handshakes, humanized their relationship, fostering an environment where negotiation could thrive. Kissinger’s ability to build trust with both superpowers, despite their mutual suspicions, was a masterclass in personal diplomacy. Brandt’s emotional gestures, such as kneeling at the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial in 1970, conveyed a sincerity that transcended political rhetoric. These moments, though symbolic, laid the groundwork for substantive agreements by shifting the tone of global dialogue from hostility to cooperation.

The legacy of these leaders’ efforts is a testament to the power of individual agency in shaping history. Détente did not end the Cold War, but it introduced mechanisms for managing conflict that remain relevant today. Their strategies offer a comparative lesson: while structural factors like mutual assured destruction constrained their options, it was their willingness to engage personally and creatively that made détente possible. For modern policymakers, the takeaway is clear: in an era of complex global challenges, the role of leadership—marked by vision, pragmatism, and empathy—remains indispensable.

Is Christine Running for Office? Unraveling Her Political Ambitions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$29.78

Economic Factors: Trade, technology, energy, interdependence, mutual benefits, reducing conflict incentives, fostering peace

Economic interdependence acts as a powerful deterrent to conflict. When nations rely on each other for trade, technology, and energy, the costs of war become prohibitively high. Consider the U.S.-China relationship: despite political tensions, their $600 billion annual trade volume creates a mutual vulnerability. Disrupting this flow would devastate both economies, making conflict a last resort. This dynamic illustrates how economic ties can override ideological differences, fostering a pragmatic peace.

Energy interdependence further amplifies this effect. Europe’s reliance on Russian natural gas, for instance, has historically tempered aggression on both sides. While this relationship has been strained by geopolitical events, it underscores the principle: when energy security is tied to cooperation, nations are less likely to risk destabilizing the status quo. Similarly, joint ventures in renewable energy technologies, such as China and the EU’s collaboration on solar panel production, create shared incentives for stability.

Technology transfer and innovation provide another layer of economic détente. The global semiconductor supply chain, involving Taiwan, South Korea, the U.S., and China, is a prime example. No single nation can dominate this process, forcing cooperation. This interdependence reduces the appeal of conflict, as any disruption would cripple industries worldwide. For instance, a 10% reduction in semiconductor production could cost the global economy $500 billion annually, a risk few nations are willing to take.

To leverage these factors effectively, policymakers should prioritize diversifying trade partners while maintaining critical interdependencies. For example, instead of decoupling entirely from China, the U.S. could expand trade with Southeast Asia, reducing vulnerability without eliminating mutual benefits. Additionally, investing in joint energy projects, such as cross-border renewable grids, can deepen interdependence in a sustainable way. Finally, establishing international tech consortia, where nations co-develop critical technologies, can ensure shared stakes in peace.

The takeaway is clear: economic factors are not just byproducts of détente but active drivers of it. By strategically fostering trade, energy, and technology interdependence, nations can create a web of mutual benefits that reduces conflict incentives. This approach doesn’t eliminate rivalry but shifts the calculus from zero-sum competition to cooperative coexistence, making peace the more rational choice.

Striking the Balance: How Polite Should Robots Be in Society?

You may want to see also

Challenges & Limits: Ideological differences, regional conflicts, mistrust, détente fragile, eventual decline, Cold War resurgence

Détente, a French term meaning "relaxation," refers to the easing of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. While this period, roughly from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, saw significant strides in arms control and diplomatic engagement, it was not without its challenges and limitations. Ideological differences between capitalism and communism remained a persistent barrier, as neither superpower was willing to abandon its core principles. These fundamental disparities often undermined efforts at genuine cooperation, as seen in the continued competition for global influence and the proxy wars that persisted in regions like Southeast Asia and Africa.

Regional conflicts further complicated détente, serving as constant reminders of the Cold War’s global reach. The Vietnam War, for instance, dragged on despite détente initiatives, while conflicts in the Middle East and Southern Africa drew both superpowers into indirect confrontations. These localized struggles often escalated tensions, as each side sought to gain strategic advantages or support allied factions. For example, the 1973 Yom Kippur War led to a near-crisis between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, with both powers mobilizing forces before a ceasefire was brokered. Such incidents highlighted the fragility of détente, as regional conflicts could quickly reignite broader hostilities.

Mistrust was another critical challenge, rooted in decades of espionage, propaganda, and military posturing. Even as leaders like Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev signed landmark agreements such as SALT I and the Helsinki Accords, both sides remained wary of the other’s intentions. This mistrust was exemplified by the continued buildup of nuclear arsenals and the persistence of intelligence operations like the Soviet penetration of Western governments. Practical steps to build trust, such as joint scientific projects or cultural exchanges, were often overshadowed by suspicions of hidden agendas, limiting the depth and sustainability of détente.

The fragile nature of détente became evident in its eventual decline, as external events and internal pressures eroded the fragile consensus. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 marked a turning point, as it was seen as a direct violation of the spirit of détente and prompted a resurgence of Cold War tensions. Domestically, political shifts in both the U.S. and the USSR contributed to the unraveling; Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 signaled a harder line against the Soviet Union, while Soviet leaders struggled to balance reformist impulses with the need to maintain control. This decline underscored the reality that détente was always a temporary reprieve rather than a permanent resolution to the Cold War.

In retrospect, the challenges and limits of détente reveal its inherent fragility and the difficulty of sustaining cooperation amid deep-seated rivalries. While it achieved notable successes in arms control and diplomatic engagement, it could not overcome the ideological, regional, and trust-based obstacles that defined the Cold War. Understanding these limitations offers valuable lessons for modern diplomacy, particularly in managing conflicts between major powers. Détente’s legacy reminds us that even incremental progress requires sustained effort, mutual respect, and a willingness to address the root causes of mistrust—elements often missing in the Cold War era.

Understanding Mansfield Politics: A Comprehensive Guide for Engaged Citizens

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Détente politics refers to a period of relaxed tensions and improved relations between opposing nations, particularly during the Cold War. It involves diplomatic efforts to reduce hostility, increase cooperation, and avoid conflict.

Détente politics began in the late 1960s and peaked in the 1970s, primarily involving the United States and the Soviet Union. Other nations, such as China and Western European countries, also played roles in fostering this era of reduced tensions.

Key agreements during détente included the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I and II), the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, and the Helsinki Accords. These aimed to limit nuclear weapons, improve human rights, and enhance diplomatic relations.

Détente declined in the late 1970s and early 1980s due to renewed tensions, such as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the deployment of intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe, and ideological differences between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.