Critical Race Theory (CRT) in politics refers to an academic framework that examines how systemic racism is embedded in legal systems, policies, and institutions, rather than solely focusing on individual biases. Emerging in the 1970s and 1980s as a response to perceived limitations in traditional civil rights approaches, CRT argues that racism is not merely a product of individual prejudice but is deeply ingrained in societal structures, perpetuating inequality. In recent years, CRT has become a contentious political issue, with critics often mischaracterizing it as a tool to divide society or promote guilt based on race, while proponents emphasize its role in understanding and addressing systemic injustices. The debate over CRT highlights broader tensions around race, education, and the role of history in shaping contemporary politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Critical Race Theory (CRT) is an academic framework examining how race and racism intersect with law, politics, and society. |

| Core Focus | Analyzes systemic racism and its embeddedness in legal and social structures. |

| Key Concepts | Intersectionality, systemic racism, microaggressions, and the role of power in perpetuating racial inequality. |

| Origins | Emerged in the 1970s and 1980s from legal scholars like Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado. |

| Application in Politics | Used to critique policies, laws, and institutions that perpetuate racial disparities. |

| Controversy | Criticized by some as divisive or anti-American; banned or restricted in education in several U.S. states. |

| Educational Context | Often taught in higher education settings, particularly in law and social sciences. |

| Misconceptions | Frequently misrepresented as teaching that one race is superior or promoting guilt based on skin color. |

| Policy Impact | Influences advocacy for racial equity in areas like criminal justice, voting rights, and education. |

| Global Relevance | Applied internationally to analyze racial inequalities beyond the U.S. context. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- CRT's Core Principles: Critical race theory examines how systemic racism shapes laws, policies, and institutions

- CRT vs. Equality: Critics argue CRT divides society by race, while supporters say it exposes inequality

- CRT in Education: Debates over teaching CRT in schools, with opponents calling it divisive

- Legal Origins of CRT: Emerged in the 1970s to address racial disparities in legal systems

- Political Backlash: CRT became a political flashpoint, with bans in some states and institutions

CRT's Core Principles: Critical race theory examines how systemic racism shapes laws, policies, and institutions

Critical Race Theory (CRT) posits that racism is not merely a product of individual bias but is deeply embedded in the fabric of society. Its core principle—that systemic racism shapes laws, policies, and institutions—challenges the notion that these structures are inherently neutral. For instance, consider the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which aimed to eliminate racial discrimination in voting. Despite its passage, CRT scholars argue that subsequent policies, such as voter ID laws, disproportionately affect minority communities, illustrating how systemic racism persists even within ostensibly equitable frameworks.

To understand CRT’s analytical lens, examine the criminal justice system. Statistics reveal that Black Americans are incarcerated at nearly five times the rate of white Americans. CRT does not attribute this disparity solely to individual actions but to systemic factors, such as biased policing practices, sentencing disparities, and the War on Drugs. By dissecting these policies, CRT highlights how institutions perpetuate racial inequality, even when explicit racial discrimination is outlawed.

A persuasive argument for CRT’s relevance lies in its call for transformative change. Unlike traditional approaches that focus on colorblind policies, CRT advocates for race-conscious solutions. For example, affirmative action programs, though controversial, aim to counteract historical and systemic disadvantages faced by marginalized groups. Critics often label such measures as "reverse racism," but CRT counters that ignoring race in a racially stratified society perpetuates existing inequalities.

Comparatively, CRT distinguishes itself from liberal or conservative frameworks by centering race as a defining feature of American society. While liberalism often emphasizes individual rights and meritocracy, CRT argues that these ideals fail to address structural barriers. Conversely, conservative critiques of CRT frequently overlook its empirical foundation, dismissing it as divisive rather than engaging with its evidence-based analysis of racial disparities in education, housing, and healthcare.

Practically, applying CRT’s principles requires a proactive approach. Policymakers, educators, and activists can use CRT as a tool to audit existing laws and institutions for racial bias. For instance, school funding formulas tied to property taxes disproportionately disadvantage minority students in underfunded districts. By identifying such mechanisms, stakeholders can advocate for equitable reforms, such as redistributing resources or implementing targeted interventions to close achievement gaps.

In conclusion, CRT’s examination of systemic racism offers a critical framework for understanding and challenging racial inequities. Its core principles demand that we look beyond surface-level neutrality to uncover how laws, policies, and institutions perpetuate racial hierarchies. By embracing this perspective, society can move toward more just and inclusive systems that address the root causes of inequality.

Unveiling the Truth: Do Political Fixers Really Exist?

You may want to see also

CRT vs. Equality: Critics argue CRT divides society by race, while supporters say it exposes inequality

Critical Race Theory (CRT) has become a lightning rod in political discourse, with its core tenets sparking intense debate. At the heart of this controversy is the clash between critics who argue that CRT divides society by race and supporters who contend that it is a necessary tool for exposing systemic inequality. This tension highlights a fundamental question: Can acknowledging racial disparities lead to greater equality, or does it perpetuate division?

Consider the classroom, a microcosm of society, where CRT’s application is often scrutinized. Critics argue that teaching students to view societal structures through a racial lens fosters resentment and guilt, pitting one race against another. For instance, a history lesson that emphasizes racial oppression without context, they claim, risks oversimplifying complex issues and alienating students. In contrast, supporters of CRT argue that ignoring these historical and systemic inequalities perpetuates ignorance and injustice. They point to examples like the disproportionate impact of the criminal justice system on Black communities, asserting that CRT provides a framework to understand and address such disparities.

To navigate this divide, it’s instructive to examine practical steps. Educators can balance CRT’s insights by pairing discussions of racial inequality with solutions-focused dialogue. For example, teaching about redlining could be followed by case studies of successful policy reforms or community initiatives that combat housing discrimination. This approach ensures students understand both the problem and the potential for change, fostering empathy rather than division. Similarly, policymakers could use CRT’s lens to identify inequities—such as disparities in healthcare access—while crafting inclusive solutions that benefit all demographics.

A comparative analysis reveals that the perceived divisiveness of CRT often stems from its misinterpretation or politicization. Critics frequently conflate CRT with simplistic notions of racial blame, while supporters sometimes overlook the need for nuanced implementation. For instance, a school district in Texas faced backlash for a CRT-inspired curriculum that lacked historical context, reinforcing stereotypes rather than challenging them. In contrast, a district in California successfully integrated CRT principles by focusing on intersectionality, showing how race intersects with class, gender, and other factors to shape outcomes.

Ultimately, the debate over CRT and equality hinges on intent and execution. When applied thoughtfully, CRT can serve as a catalyst for understanding and addressing systemic inequalities without resorting to racial essentialism. However, its effectiveness depends on how it is taught and implemented. By prioritizing context, balance, and actionable solutions, society can harness CRT’s insights to build a more equitable future without falling into the trap of division. The challenge lies in moving beyond ideological battles to focus on tangible outcomes that benefit everyone.

Why I Never Cared About Politics—Until Reality Changed My Mind

You may want to see also

CRT in Education: Debates over teaching CRT in schools, with opponents calling it divisive

Critical Race Theory (CRT) has become a lightning rod in educational policy debates, with opponents arguing its inclusion in curricula fosters division rather than understanding. At its core, CRT examines how systemic racism is embedded in legal systems and institutions, challenging the notion of a post-racial society. When applied to education, it encourages students to analyze historical and contemporary racial inequalities, often through interdisciplinary lenses like history, sociology, and law. Critics, however, claim this approach indoctrinates students with a one-sided narrative, pitting racial groups against each other and undermining national unity.

Consider the practical implementation: a high school history lesson might explore the legacy of redlining in urban development, using maps and census data to illustrate its impact on wealth disparities. Proponents argue this equips students with critical thinking skills and a deeper understanding of societal structures. Opponents counter that such lessons oversimplify complex issues, labeling individuals based on race rather than fostering individual responsibility. The debate often hinges on the age-appropriateness of these discussions, with some arguing that younger students may not possess the cognitive maturity to engage with CRT concepts without feeling guilt or resentment.

The divisiveness of CRT in education is further amplified by its politicization. State legislatures across the U.S. have introduced bills to restrict or ban CRT-related teachings, often under the guise of protecting students from "divisive concepts." These measures, however, frequently lack clear definitions of CRT, leading to confusion among educators and self-censorship in classrooms. For instance, a teacher might avoid discussing the Tuskegee Syphilis Study—a stark example of racial injustice in medical history—for fear of running afoul of vague regulations. This chilling effect stifles academic freedom and limits students’ exposure to diverse perspectives.

A comparative analysis reveals that countries like Germany and South Africa incorporate critical examinations of historical injustices into their curricula without sparking similar backlash. Germany’s approach to teaching the Holocaust emphasizes collective responsibility and the dangers of unchecked prejudice, fostering a culture of remembrance and accountability. In contrast, the U.S. debate over CRT often frames such teachings as attacks on national identity rather than opportunities for growth. This suggests that the divisiveness may stem less from CRT itself and more from broader cultural anxieties about race and history.

Ultimately, the debate over CRT in education reflects deeper societal tensions about how to address racial inequality. While opponents argue it divides students, proponents contend that ignoring systemic racism perpetuates harm. A balanced approach might involve integrating CRT principles into broader discussions of social justice, ensuring lessons are age-appropriate and encourage dialogue rather than dogma. Educators could, for example, pair historical case studies with local community projects, allowing students to apply critical analysis to real-world issues. By reframing the conversation, schools can navigate this contentious terrain and prepare students to engage thoughtfully with an increasingly diverse world.

Sonia Gandhi's Political Journey: From Housewife to Congress Leader

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legal Origins of CRT: Emerged in the 1970s to address racial disparities in legal systems

Critical Race Theory (CRT) emerged in the 1970s as a direct response to the persistent racial disparities within the American legal system. Rooted in the frustrations of civil rights activists and legal scholars, CRT challenged the notion that the law was a neutral arbiter of justice. Instead, its founders argued that the legal system itself was complicit in perpetuating racial inequality, often under the guise of colorblindness. This framework was not merely academic; it was a call to action, urging legal professionals to confront the systemic biases embedded in laws, policies, and judicial decisions.

One of the key figures in CRT’s development was Derrick Bell, a Harvard Law School professor who critiqued the limitations of the civil rights movement’s legal victories. Bell’s concept of "interest convergence" posited that progress for racial minorities only occurs when it aligns with the interests of white people. This idea underscored CRT’s emphasis on examining how race and power intersect within legal institutions. For instance, while the 1954 *Brown v. Board of Education* decision desegregated schools, its implementation was slow and uneven, revealing the legal system’s reluctance to enforce true equality.

CRT’s methodology involves interrogating legal texts, court decisions, and societal norms to expose their racial underpinnings. For example, the theory highlights how seemingly race-neutral policies, such as mandatory minimum sentencing laws, disproportionately affect communities of color. By analyzing these patterns, CRT scholars argue that the law is not a static set of rules but a dynamic tool shaped by historical and cultural contexts. This approach has been instrumental in advocating for reforms that address systemic racism rather than individual acts of discrimination.

Despite its academic origins, CRT has practical implications for legal advocacy. It encourages lawyers and policymakers to adopt a race-conscious lens when crafting laws and interpreting cases. For instance, CRT-inspired litigation has challenged voter suppression tactics, housing discrimination, and police brutality, framing these issues as symptoms of broader systemic racism. However, this approach has also sparked controversy, with critics arguing that it divides society by race rather than promoting unity.

In conclusion, the legal origins of CRT in the 1970s marked a pivotal shift in how racial disparities are understood and addressed within the legal system. By exposing the law’s role in perpetuating inequality, CRT provides a critical framework for dismantling systemic racism. Its legacy is evident in ongoing efforts to reform legal institutions and ensure that justice is not just blind but equitable. For those seeking to combat racial injustice, CRT offers both a diagnostic tool and a roadmap for change.

Is Pointing Polite? Exploring Cultural Norms and Social Etiquette

You may want to see also

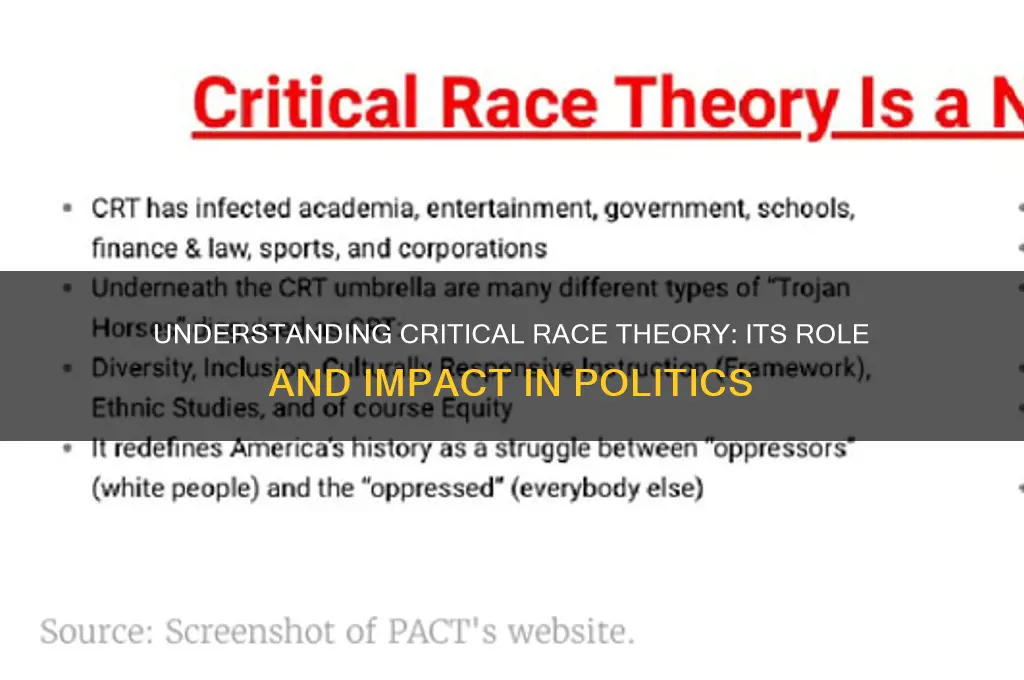

Political Backlash: CRT became a political flashpoint, with bans in some states and institutions

Critical Race Theory (CRT), an academic framework examining systemic racism, has ignited fierce political backlash, culminating in bans across several states and institutions. This reaction is not merely about the theory itself but reflects broader cultural and ideological divides. Opponents argue CRT fosters division by focusing on racial identity, while proponents counter that it provides essential tools to address entrenched inequalities. The bans, often framed as protecting "American values," have transformed CRT into a symbol of the culture wars, with classrooms and school boards becoming battlegrounds.

Consider the mechanics of these bans. Legislation in states like Texas and Florida prohibits teaching that one race or sex is inherently superior or that individuals bear guilt for historical injustices. While these laws often don’t explicitly mention CRT, they target its core tenets. Schools and educators face penalties for non-compliance, creating a chilling effect on curriculum design. For instance, a high school teacher in Tennessee was reprimanded for discussing systemic racism in a history lesson, illustrating how broadly these restrictions can be applied.

The backlash against CRT also reveals a strategic shift in conservative politics. By framing CRT as a threat to national unity, opponents have mobilized voters and shifted public discourse. Polls show that while many Americans are unfamiliar with CRT, its portrayal as "anti-American" has resonated with certain demographics. This narrative has been amplified through media outlets and social media, often distorting the theory’s academic origins and practical applications. The result is a polarized debate where nuanced discussion is overshadowed by ideological posturing.

Institutions, too, have felt the impact. Universities, traditionally bastions of free inquiry, face pressure to limit CRT-related coursework. For example, the University of North Carolina system faced scrutiny for its diversity and inclusion programs, with critics alleging they promoted CRT. Such actions not only stifle academic freedom but also hinder efforts to address racial disparities. Students and faculty are left navigating a landscape where intellectual exploration is increasingly constrained by political agendas.

Ultimately, the backlash against CRT is a symptom of deeper societal tensions. Bans may provide short-term political gains, but they fail to address the underlying issues CRT seeks to examine. Educators and policymakers must balance competing interests while fostering an environment where difficult conversations about race and history can occur. Without this, the bans risk perpetuating ignorance rather than promoting understanding, leaving future generations ill-equipped to confront the complexities of racial inequality.

Asking for Financial Help: A Guide to Polite and Effective Requests

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

CRT stands for Critical Race Theory, a framework that examines how systemic racism and historical inequalities impact society, law, and politics.

CRT is primarily an academic and legal framework used in higher education and law schools. While its concepts may influence discussions of race and history in K-12 education, it is not a standard part of the curriculum.

CRT is controversial because critics argue it divides society by race, promotes guilt, or undermines traditional values. Supporters counter that it provides a necessary lens to address systemic racism and inequality.