CR politics, short for Critical Race Theory politics, refers to a framework that examines how race and racism are deeply embedded in legal systems, societal structures, and everyday life. Rooted in the belief that racism is not merely the product of individual bias but is systemic and institutionalized, CR politics challenges traditional notions of equality and neutrality. It highlights how historical and ongoing racial inequalities are perpetuated through laws, policies, and cultural norms, advocating for transformative change rather than incremental reforms. By centering the experiences of marginalized communities, particularly Black and Indigenous people, CR politics seeks to dismantle racial hierarchies and promote justice, equity, and liberation. This approach has sparked both significant academic discourse and intense political debate, as it confronts the uncomfortable realities of racial power dynamics in society.

Explore related products

$51.11 $54.99

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Brief history and core principles of CR politics

- Key Issues Addressed: Focus on race, class, gender, and intersectionality

- Strategies and Tactics: Direct action, coalition-building, and grassroots organizing methods

- Notable Figures and Movements: Influential leaders and historical CR campaigns

- Criticisms and Challenges: Debates, limitations, and internal/external opposition to CR politics

Definition and Origins: Brief history and core principles of CR politics

Critical Race Theory (CRT) emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as a framework to analyze how race and racism are embedded in legal systems, institutions, and societal structures. Unlike traditional civil rights approaches, which often focused on individual acts of discrimination, CRT examines systemic racism—the ways in which racial inequality is perpetuated through laws, policies, and cultural norms, often invisibly. Its origins trace back to legal scholars like Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado, who critiqued the limitations of colorblind legal strategies and argued that racism is not merely a product of individual bias but a foundational element of American society. This perspective was born out of the realization that legal victories in the civil rights era had not eradicated racial disparities, prompting a deeper exploration of race as a social construct and its enduring impact.

At its core, CRT is built on several key principles. First, it asserts that racism is ordinary, not aberrational—it is a regular feature of societal functioning rather than an exception. Second, CRT emphasizes the role of storytelling and lived experiences in understanding racial inequality, often centering narratives from marginalized communities to challenge dominant, often white-centric, perspectives. Third, it critiques the idea of meritocracy, arguing that systems are designed to maintain racial hierarchies, regardless of individual effort or talent. Finally, CRT advocates for an intersectional approach, recognizing that race intersects with other identities like gender, class, and sexuality to create unique forms of oppression. These principles distinguish CRT from other racial theories, making it a powerful tool for uncovering and addressing systemic injustices.

To understand CRT’s practical application, consider its influence on education policy. CRT scholars argue that seemingly neutral policies, such as standardized testing or school funding formulas tied to property taxes, disproportionately disadvantage students of color. For instance, schools in low-income, predominantly Black or Latino neighborhoods often receive fewer resources, perpetuating educational inequalities. CRT encourages policymakers to examine these structures critically, asking how they maintain racial disparities rather than assuming they are inherently fair. This approach has sparked both adoption in academic circles and fierce debate in public discourse, highlighting CRT’s ability to challenge established norms.

Despite its academic roots, CRT has become a contentious topic in political and cultural debates. Critics often mischaracterize it as teaching "white guilt" or promoting division, while proponents argue it is essential for fostering an honest dialogue about race. This polarization underscores the theory’s disruptive potential—it forces society to confront uncomfortable truths about racial inequality. For those interested in applying CRT principles, start by examining local policies or institutional practices through a systemic lens. Ask: Who benefits? Who is excluded? And how can these systems be reimagined to promote equity? This methodical approach aligns with CRT’s call to action, transforming analysis into advocacy for meaningful change.

Mastering the Campaign Trail: Strategies to Secure Political Office

You may want to see also

Key Issues Addressed: Focus on race, class, gender, and intersectionality

Critical Race Theory (CRT) politics centers on dismantling systemic inequalities by examining how race, class, gender, and their intersections shape power structures. Unlike approaches that treat these categories in isolation, CRT insists on their interconnectedness, revealing how, for example, a Black woman’s experience of discrimination cannot be reduced to either racism or sexism alone. This framework challenges the notion of a neutral legal or political system, arguing instead that institutions inherently perpetuate racial, class, and gender hierarchies. By foregrounding lived experiences and historical contexts, CRT politics demands a radical rethinking of justice, equity, and policy-making.

Consider the wage gap: while it’s commonly framed as a gender issue (women earning 82 cents for every dollar earned by men), intersectional analysis exposes deeper disparities. Black women earn only 63 cents, and Latina women just 55 cents, for the same work. These statistics illustrate how race and class compound gender inequality, creating distinct barriers for marginalized groups. CRT politics urges policymakers to address these disparities not through blanket solutions but through targeted interventions that account for overlapping identities. For instance, raising the minimum wage alone won’t close these gaps unless paired with anti-discrimination measures in hiring and promotion practices.

To operationalize CRT in policy, start by disaggregating data. Instead of lumping all "women" or "minorities" into single categories, break down statistics by race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. This reveals hidden inequities and ensures resources are allocated where they’re most needed. For example, education reforms often focus on "low-income students" without distinguishing between Black, Latinx, and white students within that group. CRT-informed policies would address how racialized poverty, segregation, and biased curriculum standards uniquely impact each subgroup, tailoring solutions accordingly.

A cautionary note: CRT politics is often mischaracterized as divisive or blame-shifting. Critics argue it fosters resentment or guilt rather than solutions. However, its aim isn’t to assign blame but to uncover systemic patterns that sustain inequality. For instance, acknowledging that Black families were excluded from mid-20th-century housing policies (like redlining) isn’t about shaming individuals today; it’s about understanding why generational wealth gaps persist and designing reparations or housing policies to correct them. Effective CRT-inspired advocacy requires clear communication to counter misinformation and build coalitions across diverse groups.

Ultimately, CRT politics offers a transformative lens for addressing inequality by refusing to silo race, class, and gender. It challenges us to ask: Whom does this policy serve? Whose voices are excluded? And how can we redistribute power more equitably? Whether in education, healthcare, or criminal justice, this approach demands specificity, historical awareness, and a commitment to uprooting intersecting systems of oppression. The takeaway is clear: equity isn’t achieved by treating everyone the same but by accounting for the unique ways privilege and marginalization manifest across identities.

Danny DeVito's Political Views: Liberal Activism and Hollywood Influence

You may want to see also

Strategies and Tactics: Direct action, coalition-building, and grassroots organizing methods

Direct action is the backbone of CR politics, a method that bypasses traditional power structures to achieve immediate, tangible results. Whether it’s a sit-in, strike, or blockade, the goal is to disrupt systems of oppression and force a response. For instance, the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the 1950s demonstrated how sustained direct action could dismantle segregation laws. When planning such actions, clarity of purpose is critical. Define the target (e.g., a corporation, policy, or institution), ensure legal preparedness, and establish clear communication channels. Direct action isn’t just about protest—it’s about creating a crisis that demands resolution, leveraging the power of visibility and collective refusal to comply.

Coalition-building, on the other hand, requires a different skill set: diplomacy, compromise, and strategic alignment. It’s about uniting diverse groups around shared goals while respecting their autonomy. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) exemplified this by bringing together LGBTQ+ activists, healthcare workers, and scientists to fight the AIDS epidemic. To build effective coalitions, start by identifying overlapping interests rather than forcing ideological uniformity. Establish mutual aid frameworks, such as resource-sharing or joint campaigns, and prioritize transparency to avoid tokenism. Coalitions amplify voices and pool resources, but they require patience and a willingness to cede control for the greater good.

Grassroots organizing is the lifeblood of CR politics, rooted in local communities and driven by those most affected by injustice. It’s about building power from the ground up, not waiting for top-down solutions. The Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast for Children program combined service with political education, fostering community self-reliance. Effective grassroots work involves deep listening—holding town halls, door-knocking, and surveying residents to understand their needs. Focus on small, winnable campaigns to build momentum, such as improving local housing conditions or securing better school funding. Train leaders within the community to sustain the movement, ensuring it remains accountable to those it serves.

These three methods—direct action, coalition-building, and grassroots organizing—are not mutually exclusive but complementary. Direct action creates urgency, coalition-building broadens support, and grassroots organizing ensures sustainability. For example, the Fight for $15 campaign combined strikes (direct action) with alliances between labor unions and racial justice groups (coalition-building) while anchoring itself in local worker stories (grassroots organizing). The key is to adapt these strategies to context: in rural areas, focus on personal relationships; in urban settings, leverage density for mass actions. Each tactic has its risks—direct action can lead to backlash, coalitions can fracture, and grassroots efforts can burn out—but when combined thoughtfully, they form a powerful toolkit for transformative change.

Lawyers in Politics: Shaping Policies or Pursuing Power?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Notable Figures and Movements: Influential leaders and historical CR campaigns

Civil Rights (CR) politics has been shaped by visionary leaders and transformative movements that challenged systemic injustices and redefined societal norms. One of the most iconic figures is Martin Luther King Jr., whose nonviolent resistance strategies, exemplified by the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington, galvanized global attention to racial inequality. King’s emphasis on peaceful protest, rooted in moral persuasion, remains a cornerstone of CR activism. His leadership not only advanced legal reforms like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 but also inspired movements worldwide, proving that collective action can dismantle entrenched oppression.

While King’s approach was rooted in nonviolence, Malcolm X offered a contrasting perspective, advocating for Black empowerment and self-defense. His unapologetic critique of systemic racism and call for racial pride resonated deeply with marginalized communities. Though often misunderstood, Malcolm X’s evolution from nationalism to a more inclusive worldview demonstrated the complexity of CR struggles. His legacy underscores the importance of diverse strategies within the broader fight for equality, reminding us that there is no single path to justice.

Beyond individual leaders, historical campaigns like the Women’s Suffrage Movement and the LGBTQ+ Rights Movement illustrate the intersectionality of CR politics. Figures such as Sojourner Truth and Harvey Milk bridged racial, gender, and sexual identity struggles, highlighting the interconnectedness of oppression. The Stonewall Riots of 1969, for instance, were a turning point for LGBTQ+ rights, showcasing how grassroots resistance can spark lasting change. These movements teach us that CR politics is not monolithic; it thrives on coalition-building and amplifying marginalized voices.

A critical takeaway from these figures and campaigns is the power of persistence. The Disability Rights Movement, led by activists like Judith Heumann, fought for decades to secure the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. Their success was not instantaneous but the result of sustained advocacy, legal battles, and public education. This underscores the need for long-term commitment in CR work, as systemic change often requires generations of effort.

Finally, modern CR movements, such as Black Lives Matter (BLM), exemplify how historical lessons are applied in contemporary contexts. Founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, BLM has reignited global conversations about police brutality and racial justice. By leveraging social media and decentralized organizing, BLM has mobilized millions, proving that CR politics adapts to new tools and tactics while staying true to its core principles. These leaders and movements remind us that the fight for equality is ongoing, and every generation must rise to the challenge.

Understanding Political Consulting: Strategies, Influence, and Campaign Success

You may want to see also

Criticisms and Challenges: Debates, limitations, and internal/external opposition to CR politics

Critical Race Theory (CRT) politics, which examines how race and racism are embedded in legal and social structures, faces significant criticisms and challenges. One central debate revolves around its perceived divisiveness. Critics argue that CRT’s focus on systemic racism fosters racial resentment and polarization by framing society as inherently oppressive. For instance, opponents often claim that teaching CRT in schools pits students against each other based on skin color, rather than promoting unity. Proponents counter that acknowledging historical and ongoing racial inequalities is necessary for progress, but this tension highlights the difficulty of balancing awareness with cohesion.

A practical limitation of CRT politics lies in its application to policy-making. While the theory identifies systemic issues, translating its insights into actionable solutions can be challenging. For example, CRT critiques colorblind policies but offers few concrete alternatives beyond broad calls for equity. This vagueness leaves policymakers struggling to implement reforms without clear frameworks, leading to accusations of ineffectiveness. Critics also point out that CRT’s emphasis on group identity can overshadow individual experiences, complicating efforts to address nuanced, intersectional issues.

Internal opposition within CRT circles further complicates its political impact. Scholars debate whether the theory should prioritize radical transformation or incremental change. Some argue for dismantling existing institutions entirely, while others advocate for working within them to achieve gradual progress. This divide weakens CRT’s unified front, making it harder to mobilize collective action. Additionally, critiques from within about its limited engagement with class-based oppression reveal blind spots that hinder broader appeal.

External opposition, particularly from conservative groups, poses a significant challenge. CRT has become a political lightning rod, with opponents framing it as a threat to national identity and meritocracy. In practice, this has led to legislative bans on CRT-related teachings in several U.S. states, stifling open dialogue about race. Such backlash underscores the theory’s struggle to gain mainstream acceptance, despite its academic roots. To navigate this, advocates must reframe CRT’s goals in accessible, less polarizing terms while emphasizing its potential to address real-world injustices.

Finally, the global applicability of CRT politics is a point of contention. Developed within the U.S. context, CRT’s focus on Black-white dynamics may not fully capture racial hierarchies in other regions. For instance, caste systems in India or indigenous rights in Latin America require distinct analytical frameworks. Critics argue that applying CRT universally risks oversimplifying these complexities. Adapting the theory to diverse contexts demands careful consideration of local histories and power structures, ensuring its relevance beyond its original scope.

Immigration and Politics: Unraveling the Complex Interplay of Policies and Power

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

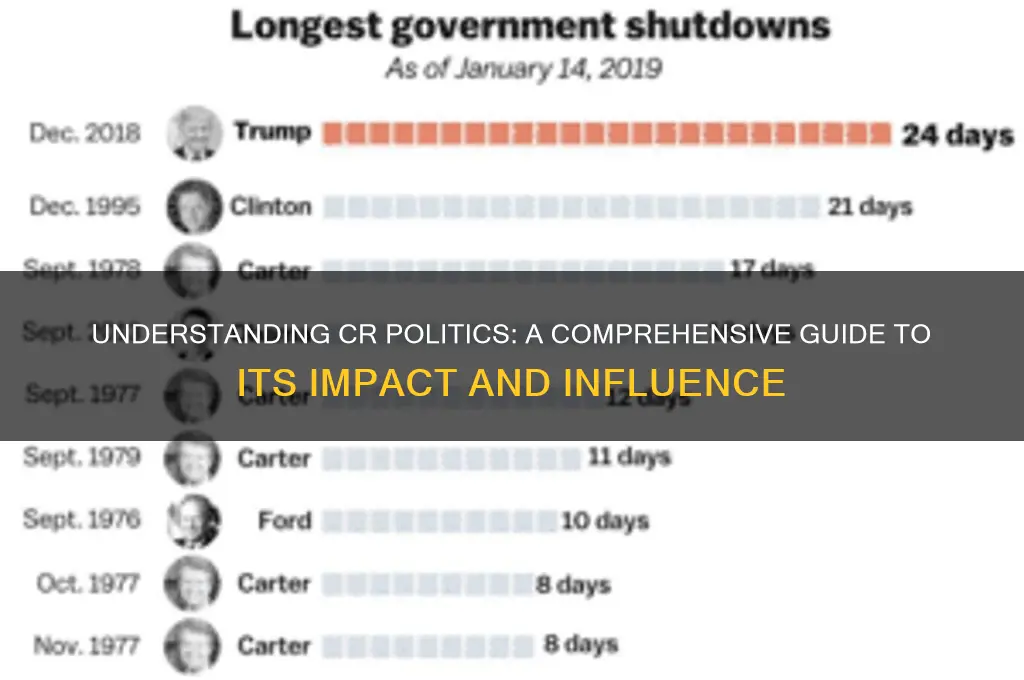

CR stands for "Congressional Record," but in the context of CR politics, it often refers to "Continuing Resolution," a temporary funding measure used by the U.S. government to avoid a shutdown when a formal budget is not in place.

A Continuing Resolution (CR) is a stopgap spending bill that maintains government funding at existing levels for a specific period, typically when Congress fails to pass a full budget before the fiscal year ends. It prevents a government shutdown by providing temporary funding.

CRs are controversial because they often reflect legislative gridlock and a lack of long-term fiscal planning. Critics argue they lead to inefficiencies, limit agencies' ability to plan, and avoid addressing critical budgetary issues, such as deficit spending or policy priorities.

A CR can last for a few days, weeks, or even months, depending on the agreement reached by Congress. However, it is intended as a temporary solution, and prolonged reliance on CRs is generally seen as a failure of the budgetary process.