Centrifugal politics refers to the forces and dynamics within a political system that push power, authority, and decision-making away from the central government and toward regional, local, or decentralized entities. Unlike centripetal forces, which unify and consolidate power, centrifugal forces often arise from cultural, ethnic, economic, or ideological differences that challenge centralized control. This phenomenon can manifest in various forms, such as regional autonomy movements, secessionist tendencies, or the devolution of power to subnational units. Centrifugal politics is often observed in diverse or fragmented societies where competing interests and identities create tension with a centralized authority, leading to debates over governance, resource distribution, and political representation. Understanding centrifugal politics is crucial for analyzing the stability and cohesion of states, particularly in multinational or multiethnic contexts where centrifugal forces can either foster diversity and local empowerment or threaten national unity and integration.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Centrifugal politics refers to forces or tendencies that pull a political entity apart, often leading to fragmentation, secession, or regional autonomy. |

| Key Drivers | Ethnic, religious, linguistic, or cultural differences; economic disparities; regional identity; perceived marginalization; lack of centralized authority. |

| Examples | Catalonia's push for independence from Spain; Kurdish separatism in the Middle East; Brexit in the UK; regional tensions in India (e.g., Northeast states). |

| Effects | Weakening of central government; rise of regional or separatist movements; potential for conflict or civil unrest; reconfiguration of political boundaries. |

| Counterforces | Centripetal forces (e.g., shared national identity, economic integration, strong central governance) that counteract centrifugal tendencies. |

| Global Trends | Increasing demands for autonomy or independence in regions like Scotland, Flanders, Hong Kong, and Tigray; rise of identity-based politics. |

| Historical Context | Often rooted in historical grievances, colonial legacies, or failed power-sharing arrangements. |

| Modern Challenges | Globalization, migration, and digital communication amplifying regional identities and grievances. |

| Resolution Methods | Federalism, devolution, power-sharing agreements, cultural autonomy, or, in extreme cases, secession. |

| Risks | Escalation into violence, economic instability, and international intervention or conflict. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition: Centrifugal forces push diverse groups apart, threatening unity and stability within a political entity

- Examples: Ethnic, religious, or regional divisions often fuel centrifugal political tensions

- Causes: Inequality, lack of representation, and cultural differences drive centrifugal tendencies

- Effects: Leads to secession, fragmentation, or weakened central authority in political systems

- Countermeasures: Federalism, autonomy, and inclusive policies mitigate centrifugal political forces

Definition: Centrifugal forces push diverse groups apart, threatening unity and stability within a political entity

Centrifugal forces in politics act like invisible hands, pulling diverse groups away from a shared center. These forces manifest as ethnic tensions, regional disparities, or ideological divides, eroding the cohesion necessary for a stable political entity. Consider the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, where centrifugal forces—fueled by ethnic nationalism and economic inequalities—shattered a once-unified state into several independent nations. This example illustrates how centrifugal forces can dismantle even long-standing political structures when left unchecked.

To counteract centrifugal forces, political leaders must adopt strategies that foster inclusivity and address root causes of division. For instance, federal systems often devolve power to regional authorities, allowing diverse groups to maintain cultural or administrative autonomy while remaining part of a larger whole. Switzerland’s model of cantonal governance is a prime example, where linguistic and cultural differences are accommodated within a unified federal framework. However, such systems require careful balance; too much decentralization can weaken central authority, while too little can exacerbate grievances.

A persuasive argument for addressing centrifugal forces lies in their potential to escalate into conflict. When groups feel marginalized or ignored, they may resort to secessionist movements or violent resistance. The ongoing tensions in Catalonia, Spain, highlight this risk, as calls for independence stem from perceived economic and cultural neglect. Policymakers must prioritize dialogue and equitable resource distribution to prevent such scenarios, ensuring no group feels systematically disadvantaged.

Comparatively, centrifugal forces are not inherently destructive; they can also drive healthy competition and innovation. In the United States, states often compete to attract businesses through tax incentives or infrastructure development, benefiting the nation as a whole. However, this dynamic requires a strong central framework to prevent competition from devolving into harmful rivalry. Striking this balance is critical: harness the energy of diversity without allowing it to fracture unity.

Practically, mitigating centrifugal forces demands proactive measures. First, invest in education that promotes cultural understanding and shared national identity. Second, implement policies that reduce economic disparities between regions or groups. Third, establish inclusive political institutions that give voice to all stakeholders. For example, proportional representation systems ensure minority groups are not systematically excluded from decision-making. By addressing these factors, political entities can transform centrifugal pressures into opportunities for growth rather than seeds of division.

Understanding International Political Organizations: Roles, Structures, and Global Impact

You may want to see also

Examples: Ethnic, religious, or regional divisions often fuel centrifugal political tensions

Centrifugal forces in politics often manifest through ethnic, religious, or regional divisions, pulling societies apart rather than uniting them. Consider the Balkans in the 1990s, where ethnic tensions between Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks erupted into a series of devastating wars. These conflicts were fueled by historical grievances, competing nationalisms, and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, illustrating how deeply rooted ethnic identities can become catalysts for political fragmentation. The Balkan Wars serve as a stark reminder that when ethnic divisions are politicized, they can dismantle even long-standing multinational states.

Religious differences, too, have proven to be powerful centrifugal forces. In India, for instance, the partition of 1947 was driven by religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims, resulting in the creation of Pakistan. This division was not merely a political event but a deeply personal and violent upheaval, displacing millions and leaving lasting scars. Even today, religious identity continues to shape political allegiances in the region, with parties often leveraging faith-based appeals to mobilize voters. Such examples highlight how religion, when intertwined with politics, can exacerbate divisions rather than foster unity.

Regional disparities also fuel centrifugal tensions, particularly in large, diverse countries. Spain’s ongoing struggle with Catalan separatism is a case in point. Catalonia’s distinct culture, language, and economic strength have fueled demands for independence, creating a persistent political crisis. The Spanish government’s response, oscillating between repression and negotiation, has only deepened the divide. This scenario underscores how regional inequalities, whether perceived or real, can drive communities to seek autonomy or secession, challenging the integrity of the nation-state.

To mitigate these centrifugal forces, policymakers must adopt inclusive strategies that address the root causes of division. For ethnic tensions, promoting multicultural education and equitable representation in governance can help bridge gaps. In religious conflicts, fostering interfaith dialogue and secular policies can reduce polarization. For regional disparities, devolving power and resources to local authorities can alleviate grievances. While these solutions are not one-size-fits-all, they offer a framework for managing diversity without resorting to fragmentation. The challenge lies in balancing unity with autonomy, ensuring that differences enrich rather than destroy the political fabric.

Discovering Your Political Identity: Unraveling the Label That Fits You Best

You may want to see also

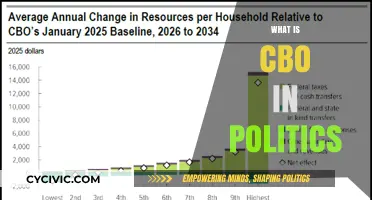

Causes: Inequality, lack of representation, and cultural differences drive centrifugal tendencies

Centrifugal politics often emerges from deep-seated inequalities that fracture societies along economic, social, or political lines. When wealth and resources are concentrated in the hands of a few, marginalized groups feel excluded from the benefits of collective progress. For instance, in countries with high Gini coefficients—such as South Africa (63.0) or Brazil (53.9)—economic disparities fuel resentment and separatism. The perception that the system is rigged against certain demographics creates fertile ground for centrifugal forces, as seen in the rise of regionalist movements demanding autonomy or secession. Addressing inequality requires more than token policies; it demands structural reforms like progressive taxation, equitable access to education, and targeted investments in underserved areas. Without these, the centrifugal pull of inequality will continue to destabilize nations.

Lack of representation in political institutions acts as a catalyst for centrifugal tendencies, as groups feel their voices are systematically ignored. Consider the Kurdish population in the Middle East, whose statelessness and exclusion from national governments have fueled decades of separatist aspirations. Similarly, in India, the demands for statehood by regions like Telangana or Gorkhaland stem from perceived neglect by central authorities. To counter this, governments must adopt inclusive governance models, such as proportional representation or reserved seats for minority groups. Practical steps include decentralizing power, conducting regular audits of political representation, and ensuring that decision-making bodies reflect the diversity of their populations. Ignoring these measures risks deepening divisions and emboldening centrifugal movements.

Cultural differences, when politicized, can become powerful drivers of centrifugal politics, particularly when identities are framed as mutually exclusive. The breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s exemplifies this, as ethnic and religious divisions were exploited to justify fragmentation. Similarly, in contemporary Belgium, tensions between Flemish and Walloon communities persist due to linguistic and cultural disparities. Mitigating this requires fostering intercultural dialogue and promoting shared national narratives that celebrate diversity rather than homogenize it. Governments can invest in cultural exchange programs, multilingual education, and media platforms that amplify minority voices. By acknowledging and valuing cultural differences, societies can reduce the centrifugal pressures that threaten their cohesion.

The interplay of inequality, lack of representation, and cultural differences creates a vicious cycle that amplifies centrifugal tendencies. For example, in Catalonia, Spain, economic grievances, political marginalization, and a distinct cultural identity converged to fuel the region’s push for independence. Breaking this cycle demands a multi-pronged approach: economic policies that reduce disparities, political systems that ensure inclusivity, and cultural frameworks that encourage unity in diversity. Policymakers must act proactively, recognizing that centrifugal forces, once unleashed, are difficult to contain. The alternative is a fragmented society where division becomes the norm, and cohesion remains an elusive ideal.

Nationalism's Dual Nature: Cultural Roots vs. Political Manifestation Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Effects: Leads to secession, fragmentation, or weakened central authority in political systems

Centrifugal forces in politics act like a spinning top, pulling power and identity outward from the center. These forces, driven by regionalism, ethnic tensions, or economic disparities, can fracture political systems in profound ways. Consider the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, where centrifugal pressures from republics like Ukraine and the Baltic states overwhelmed the central authority, leading to secession and fragmentation. This example illustrates how centrifugal politics can dismantle even the most formidable political structures.

To understand the mechanics, imagine a political system as a magnet holding diverse regions together. When centrifugal forces intensify—whether through cultural grievances, resource disputes, or autonomy demands—the magnet weakens. Regions begin to act independently, eroding the central government’s ability to enforce laws or collect taxes. For instance, Catalonia’s push for independence from Spain highlights how economic disparities and cultural identity can fuel secessionist movements, leaving the central authority weakened and reactive.

A step-by-step analysis reveals how centrifugal politics escalates. First, localized grievances fester, often ignored by distant central governments. Second, these grievances coalesce into organized movements demanding autonomy or resources. Third, if unaddressed, these movements may declare independence or form parallel governance structures. Finally, the central authority, now fragmented, struggles to maintain control, leading to political instability. This pattern is evident in countries like Sudan, where centrifugal forces resulted in South Sudan’s secession in 2011.

Practical tips for mitigating these effects include fostering inclusive governance, addressing regional inequalities, and devolving power to local authorities. For instance, Switzerland’s cantonal system demonstrates how decentralization can accommodate diversity without sacrificing unity. Conversely, ignoring centrifugal pressures, as seen in Myanmar’s treatment of ethnic minorities, can exacerbate fragmentation and violence. The takeaway is clear: centrifugal politics demands proactive, inclusive solutions to prevent systemic collapse.

Comparatively, centrifugal forces in federal systems like the United States manifest differently than in unitary states. While states’ rights debates create tension, the Constitution’s framework provides a buffer against outright secession. In contrast, unitary states like Spain or Sri Lanka face greater risks when centrifugal forces emerge, as their centralized structures offer fewer outlets for regional aspirations. This comparison underscores the importance of political architecture in managing centrifugal pressures.

In conclusion, centrifugal politics is a powerful destabilizer, capable of leading to secession, fragmentation, or weakened central authority. Its effects are predictable yet often underestimated, as seen in historical and contemporary examples. By understanding its mechanics and adopting proactive strategies, political systems can mitigate its destructive potential and preserve unity in diversity.

Understanding Panhandling in Politics: Tactics, Ethics, and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Countermeasures: Federalism, autonomy, and inclusive policies mitigate centrifugal political forces

Centrifugal forces in politics pull societies apart, fueled by regional disparities, cultural divisions, or economic inequalities. These forces manifest as secessionist movements, ethnic conflicts, or political fragmentation. Yet, nations can counteract these pressures through deliberate structural and policy interventions. Federalism, autonomy, and inclusive policies emerge as potent countermeasures, offering frameworks that balance unity with diversity.

Consider federalism as a structural antidote. By devolving power to regional or state governments, federal systems allow local identities to flourish without threatening national cohesion. For instance, Germany’s federal model grants its 16 states (Länder) significant autonomy in education, culture, and policing, reducing centrifugal tensions by addressing regional needs directly. Similarly, India’s federal structure accommodates linguistic and cultural diversity, preventing the dominance of any single group. However, federalism requires careful calibration; over-decentralization can weaken central authority, while under-decentralization may fail to appease regional demands. A rule of thumb: allocate at least 40% of fiscal resources to subnational units, as seen in successful models like Canada and Switzerland.

Autonomy arrangements serve as a middle ground between full federalism and centralized control. These grant specific regions self-governance in cultural, linguistic, or administrative matters. Spain’s Basque Country and Catalonia exemplify this approach, with devolved powers over taxation, education, and healthcare. Such autonomy reduces grievances by allowing regions to preserve their distinct identities. However, autonomy must be paired with clear legal frameworks to avoid ambiguity. For instance, the 2004 Spanish Organic Law on Education ensured regional curricula aligned with national standards, balancing autonomy with unity. Caution: autonomy without equitable resource distribution can exacerbate inequalities, so ensure funding formulas prioritize disadvantaged regions.

Inclusive policies act as the soft power complement to structural reforms. By integrating marginalized groups into political, economic, and social spheres, these policies dismantle the root causes of centrifugal forces. South Africa’s post-apartheid affirmative action policies and Rwanda’s post-genocide unity programs illustrate this approach. Practical steps include quotas for underrepresented groups in legislatures (e.g., 30% women in Rwanda’s parliament), targeted economic development in marginalized regions, and cultural recognition initiatives. For instance, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission addresses Indigenous grievances through policy reforms and public awareness campaigns. Key takeaway: inclusive policies must be proactive, not reactive, and backed by measurable targets and timelines.

In implementing these countermeasures, leaders must avoid common pitfalls. Federalism and autonomy require robust conflict resolution mechanisms, such as constitutional courts or mediation bodies. Inclusive policies demand sustained political will and public buy-in, often achieved through civic education and participatory governance. For instance, Belgium’s complex federal system relies on regular intergovernmental consultations to manage linguistic and regional divides. Ultimately, the success of these measures hinges on their adaptability—what works in one context may fail in another. Tailor strategies to local realities, monitor outcomes, and adjust as needed. In the battle against centrifugal forces, flexibility is as vital as structure.

Military's Dual Role: Economic Powerhouse or Political Tool?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Centrifugal politics refers to forces or tendencies within a political system that push for decentralization, fragmentation, or the breakup of centralized authority. These forces often arise from regional, ethnic, cultural, or ideological differences that challenge the unity of a state or organization.

Examples include separatist movements (e.g., Catalonia in Spain), regional autonomy demands, ethnic or religious conflicts, and ideological divisions that weaken national cohesion. These forces often lead to the formation of independent states, autonomous regions, or political instability.

While centrifugal politics involves forces that pull a political system apart, centripetal politics focuses on forces that unify or centralize it. Centripetal forces include shared national identity, common cultural values, strong central institutions, and policies that promote unity and integration.