Capitalism in politics refers to the economic and political system where private individuals or corporations own and control the means of production and distribution of goods and services, with the goal of generating profit. In this system, markets play a dominant role in allocating resources, and competition drives innovation and efficiency. Politically, capitalism often aligns with ideologies that emphasize individual freedom, limited government intervention, and the protection of private property rights. However, its implementation varies across countries, with some adopting a more laissez-faire approach while others incorporate regulatory measures to address issues like inequality, market failures, and social welfare. The interplay between capitalism and politics shapes policies on taxation, trade, labor rights, and economic regulation, often sparking debates about the balance between economic growth and social equity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Private Ownership | Emphasis on individual or corporate ownership of resources and production. |

| Market Economy | Reliance on supply and demand to determine prices and allocate resources. |

| Profit Motive | Pursuit of financial gain as the primary driving force for businesses. |

| Competition | Encouragement of competition among businesses to drive innovation and efficiency. |

| Limited Government Intervention | Minimal state involvement in economic affairs, favoring free markets. |

| Wage Labor | Workers are paid wages for their labor, often in exchange for profit. |

| Capital Accumulation | Focus on investing profits back into production to expand wealth. |

| Globalization | Promotion of international trade and investment to expand markets. |

| Inequality | Acceptance of wealth disparities as a natural outcome of competition. |

| Consumerism | Encouragement of consumption as a driver of economic growth. |

| Innovation and Entrepreneurship | Support for creativity and risk-taking to develop new products and services. |

| Property Rights | Strong protection of private property and intellectual rights. |

| Financial Markets | Reliance on stock markets, banking, and investment to allocate capital. |

| Economic Freedom | Emphasis on individual liberty to make economic decisions. |

| Resource Exploitation | Utilization of natural resources for economic gain, often with environmental consequences. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Capitalism's Role in Democracy: How free markets influence democratic systems and political decision-making

- Wealth Inequality: Capitalism's impact on income gaps and political power distribution

- Corporate Influence: Role of corporations in shaping political policies and elections

- Laissez-Faire vs. Regulation: Balancing free markets with government intervention in capitalist systems

- Global Capitalism: How capitalism drives international politics and economic relationships

Capitalism's Role in Democracy: How free markets influence democratic systems and political decision-making

Capitalism, as an economic system, inherently shapes democratic processes by intertwining financial power with political influence. In democratic systems, free markets often dictate the flow of resources, which in turn affects political decision-making. Wealthy individuals and corporations, leveraging their economic might, can disproportionately sway policies through lobbying, campaign financing, and media control. For instance, in the United States, the Citizens United v. FEC ruling allowed corporations to spend unlimited funds on political campaigns, blurring the line between economic and political power. This dynamic raises a critical question: Can a democracy truly represent the will of the people when financial interests hold such sway?

Consider the role of campaign financing as a practical example. In many democracies, candidates rely on private donations to fund their campaigns. While this system fosters competition, it also creates a dependency on wealthy donors or corporations. A study by the Center for Responsive Politics found that in the 2020 U.S. elections, candidates who spent the most won 91% of House races and 86% of Senate races. This correlation suggests that financial resources, rather than popular support, often determine electoral outcomes. For democracies to remain equitable, implementing public financing options or strict donation caps could mitigate this imbalance, ensuring that political power isn’t auctioned to the highest bidder.

The influence of capitalism on democracy extends beyond elections to policy formulation. Free markets prioritize profit, which can conflict with public welfare. For example, industries like fossil fuels or pharmaceuticals often lobby against regulations that could reduce their profits, even if those regulations benefit society at large. In the European Union, the lobbying efforts of Big Tech companies have delayed stringent data privacy laws. To counter this, democracies must strengthen transparency measures, such as mandatory disclosure of lobbying activities and stricter conflict-of-interest rules for policymakers. Without such safeguards, democratic decisions risk becoming captive to corporate interests.

A comparative analysis reveals that the degree of capitalist influence on democracy varies across nations. In Scandinavian countries, robust social welfare systems and strict campaign finance regulations limit the dominance of economic elites. Conversely, in countries with weaker regulatory frameworks, like India or Brazil, corporate influence often undermines democratic ideals. This disparity highlights the importance of institutional design: democracies must actively structure their systems to balance market forces with public interests. For instance, proportional representation systems can dilute the power of wealthy donors by diversifying political voices.

Ultimately, capitalism’s role in democracy is a double-edged sword. While free markets drive innovation and economic growth, they can also distort political decision-making if left unchecked. Democracies must adopt proactive measures, such as public financing of elections, stringent lobbying regulations, and inclusive policy-making processes, to ensure that economic power does not overshadow the voice of the people. By striking this balance, democracies can harness the benefits of capitalism while preserving their core principles of equality and representation.

Mastering Political Statecraft: Strategies, Influence, and Power Dynamics Explained

You may want to see also

Wealth Inequality: Capitalism's impact on income gaps and political power distribution

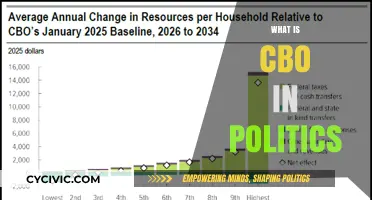

Capitalism, as an economic system, inherently fosters wealth accumulation in the hands of a few, exacerbating income inequality. This disparity is not merely a byproduct but a structural feature of capitalist politics. Consider the United States, where the top 1% of households own nearly 35% of the country's wealth, while the bottom 50% hold just 2%. This imbalance is not static; it grows as capitalist policies prioritize profit over equitable distribution. Tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy, deregulation, and weakened labor unions are political decisions that directly widen the wealth gap. These policies, often justified as incentives for economic growth, instead create a system where the rich amass more wealth, leaving the majority with limited access to resources and opportunities.

To understand capitalism's impact on political power distribution, examine campaign financing. In many capitalist democracies, political influence is directly proportional to wealth. For instance, in the U.S., the Citizens United v. FEC ruling allowed corporations and wealthy individuals to spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns through Super PACs. This has skewed policy-making in favor of the affluent, as politicians become beholden to their donors rather than the electorate. A study by Princeton University found that the preferences of the average American have little to no impact on public policy, while the wealthy and special interests hold significant sway. This erosion of democratic principles highlights how capitalism not only creates economic inequality but also translates it into political inequality.

Addressing wealth inequality requires systemic reforms, but implementing them is challenging due to the very power dynamics capitalism creates. Progressive taxation, for example, is a proven tool to reduce income gaps. Countries like Sweden and Denmark, with top marginal tax rates exceeding 50%, have lower wealth inequality compared to the U.S., where the top rate is 37%. However, political resistance from the wealthy and their allies often stalls such reforms. Practical steps include advocating for campaign finance reform to reduce the influence of money in politics, strengthening labor unions to negotiate fair wages, and investing in public education and healthcare to level the playing field. These measures, while not exhaustive, are essential to mitigating capitalism's distortive effects on wealth and power distribution.

A comparative analysis reveals that capitalism's impact on wealth inequality is not uniform across all societies. In countries with robust social safety nets and strong regulatory frameworks, the adverse effects are somewhat mitigated. For instance, Germany's model of social market economy combines free-market principles with extensive social welfare programs, resulting in lower income inequality compared to the U.S. This suggests that while capitalism inherently tends toward inequality, its severity depends on political choices. Policymakers must prioritize equitable growth over unfettered capitalism, ensuring that economic systems serve the many, not just the few. The takeaway is clear: wealth inequality is not an inevitable consequence of capitalism but a result of specific political decisions that can be reversed.

How Texas Politics Really Shape National Policies and Trends

You may want to see also

Corporate Influence: Role of corporations in shaping political policies and elections

Corporations wield significant power in shaping political policies and elections, often operating behind the scenes to influence outcomes that align with their interests. Through lobbying, campaign contributions, and strategic partnerships, they ensure that legislative agendas favor their bottom lines. For instance, the pharmaceutical industry has successfully lobbied for policies that protect drug pricing models, while tech giants have influenced data privacy laws to maintain their business models. This systemic involvement raises questions about whose interests—public or private—truly drive political decision-making.

Consider the mechanics of corporate influence: lobbying firms, often staffed by former lawmakers, act as intermediaries between corporations and politicians. These firms leverage their insider knowledge to draft legislation, amend bills, and secure favorable votes. For example, the fossil fuel industry has spent billions lobbying against climate regulations, delaying critical environmental policies. Similarly, corporations use Political Action Committees (PACs) to funnel money into campaigns, creating a quid pro quo dynamic where elected officials feel obligated to support corporate-friendly policies. This process is not inherently illegal but blurs the line between democracy and plutocracy.

The impact of corporate influence is most visible during election seasons. Corporations fund political ads, sponsor think tanks, and even bankroll astroturfing campaigns to sway public opinion. A notable example is the role of Big Tobacco in the 1990s, where companies funded research and media campaigns to downplay the harms of smoking while lobbying against regulation. Today, tech companies like Meta and Google face scrutiny for their role in spreading political ads that target specific demographics, often with minimal transparency. These tactics not only shape election outcomes but also erode public trust in democratic institutions.

To mitigate corporate overreach, practical steps can be taken. First, implement stricter campaign finance reforms, such as capping corporate donations and requiring real-time disclosure of political spending. Second, strengthen lobbying regulations by imposing cooling-off periods for former lawmakers and mandating public records of all lobbying activities. Third, empower grassroots movements and small donors through matching funds programs, leveling the playing field for candidates who rely on public support rather than corporate backing. These measures, while challenging to enact, are essential to reclaiming the democratic process from corporate dominance.

Ultimately, the role of corporations in politics is a double-edged sword. While they contribute to economic growth and innovation, their unchecked influence undermines the principles of equality and representation. By understanding the mechanisms of corporate power and advocating for systemic reforms, citizens can work toward a political landscape where policies serve the public good, not just private profits. The challenge lies in balancing corporate participation with democratic integrity—a task that requires vigilance, transparency, and collective action.

Faith's Influence: Shaping Political Landscapes and Ideologies Over Time

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Laissez-Faire vs. Regulation: Balancing free markets with government intervention in capitalist systems

Capitalism thrives on the tension between unfettered markets and necessary oversight. Laissez-faire capitalism, rooted in the French phrase meaning "let do, let pass," advocates minimal government intervention, allowing market forces to dictate production, pricing, and resource allocation. This approach, championed by classical economists like Adam Smith, posits that self-interest and competition naturally lead to efficient outcomes. For instance, in the tech sector, laissez-faire principles have enabled rapid innovation, with companies like Apple and Google flourishing in environments with limited regulatory barriers. However, this hands-off approach can exacerbate inequalities and market failures, as seen in the 2008 financial crisis, where deregulated banking practices led to systemic collapse.

Regulation, on the other hand, seeks to correct market failures and protect public interests. Government intervention can take many forms, from antitrust laws to environmental standards. For example, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 in the U.S. aimed to prevent monopolies, ensuring fair competition. Similarly, regulations like the Clean Air Act address externalities, such as pollution, which markets often ignore. Yet, overregulation can stifle innovation and create inefficiencies. Small businesses, for instance, often struggle with compliance costs, which can hinder growth. Striking the right balance requires a nuanced understanding of when and how to intervene.

A practical approach to balancing laissez-faire and regulation involves targeted interventions rather than blanket policies. For instance, industries with high potential for market failure, such as healthcare and finance, may require stricter oversight. In healthcare, regulations like the Affordable Care Act aim to ensure access while maintaining market dynamics. Conversely, sectors with low barriers to entry, like retail, may thrive with minimal intervention. Policymakers must also consider timing: during economic booms, lighter regulation may encourage growth, while crises may necessitate tighter controls.

Persuasively, the argument for balance hinges on recognizing capitalism’s dual nature—its capacity for innovation and its tendency toward excess. Laissez-faire purists often overlook the social costs of unchecked markets, while regulation advocates may underestimate the stifling effects of bureaucracy. A middle ground, such as the Nordic model, combines free markets with robust social safety nets, achieving both economic dynamism and equity. This hybrid approach demonstrates that capitalism’s success lies not in extremes but in thoughtful calibration.

In conclusion, the debate between laissez-faire and regulation is not a binary choice but a spectrum. Effective capitalist systems require a dynamic interplay between market freedom and government intervention, tailored to specific contexts and challenges. By learning from historical examples and adapting policies to evolving conditions, societies can harness capitalism’s strengths while mitigating its weaknesses. The key lies in recognizing that the goal is not to eliminate one approach in favor of the other but to integrate them intelligently for sustainable prosperity.

Understanding Non-Electoral Politics: Power, Influence, and Civic Engagement Beyond Voting

You may want to see also

Global Capitalism: How capitalism drives international politics and economic relationships

Capitalism, as an economic system, thrives on the principles of private ownership, profit-seeking, and market competition. When scaled globally, it becomes a dominant force shaping international politics and economic relationships. At its core, global capitalism fosters interdependence among nations, as countries specialize in producing goods and services where they have a comparative advantage, creating a complex web of trade and investment flows. For instance, China’s manufacturing prowess and Germany’s engineering expertise are not just national strengths but pillars of the global economy, illustrating how capitalism drives nations to integrate into a larger, interconnected system.

Consider the role of multinational corporations (MNCs) as prime movers in this dynamic. Companies like Apple, Toyota, and Shell operate across borders, leveraging resources, labor, and markets worldwide to maximize profits. Their decisions often influence national policies, as governments compete to attract foreign investment by offering tax incentives, deregulation, or infrastructure improvements. This corporate-state interplay highlights how capitalism not only drives economic growth but also shapes political priorities, sometimes at the expense of local industries or environmental sustainability. For example, the race to host tech giants like Tesla has led to significant policy shifts in countries like India and Mexico, demonstrating capitalism’s power to dictate political agendas.

However, global capitalism is not without its contradictions. While it promotes economic growth and innovation, it also exacerbates inequality, both within and between nations. Wealth accumulates in the hands of a few, as seen in the growing gap between the global North and South. Developing countries often find themselves trapped in cycles of debt and dependency, supplying raw materials and cheap labor while receiving limited benefits from the global market. This imbalance raises ethical questions about the fairness of a system that prioritizes profit over equitable development, prompting calls for reforms such as fair trade policies or global tax agreements to address these disparities.

To navigate the complexities of global capitalism, nations must adopt strategic approaches that balance economic growth with social and environmental responsibility. For instance, the European Union’s Green Deal aims to align economic activities with sustainability goals, while initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area seek to enhance regional economic integration. Policymakers must also address the challenges posed by digital capitalism, where tech giants dominate global markets, often evading traditional regulatory frameworks. By fostering international cooperation and innovative policies, countries can harness the benefits of capitalism while mitigating its adverse effects, ensuring a more inclusive and sustainable global order.

In conclusion, global capitalism is a double-edged sword that drives international politics and economic relationships through its emphasis on competition, profit, and interdependence. While it fuels growth and innovation, it also deepens inequalities and poses ethical dilemmas. Understanding its mechanisms and contradictions is crucial for crafting policies that maximize its benefits while addressing its shortcomings. As the global economy continues to evolve, the challenge lies in creating a system that works for all, not just the few.

Exploring Michael Bloomberg's Political Record: Policies, Achievements, and Controversies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Capitalism in politics refers to an economic and political system where the means of production and distribution are privately owned and operated for profit, often with minimal government intervention. It emphasizes free markets, competition, and individual ownership of resources.

Capitalism influences political decision-making by prioritizing economic growth, private enterprise, and market efficiency. Policies often favor deregulation, lower taxes for businesses, and protection of private property rights, reflecting the interests of capitalists and corporations.

Critics argue that capitalism in politics can lead to wealth inequality, exploitation of workers, and environmental degradation. They also claim it prioritizes profit over social welfare, often resulting in policies that benefit the wealthy at the expense of the marginalized.