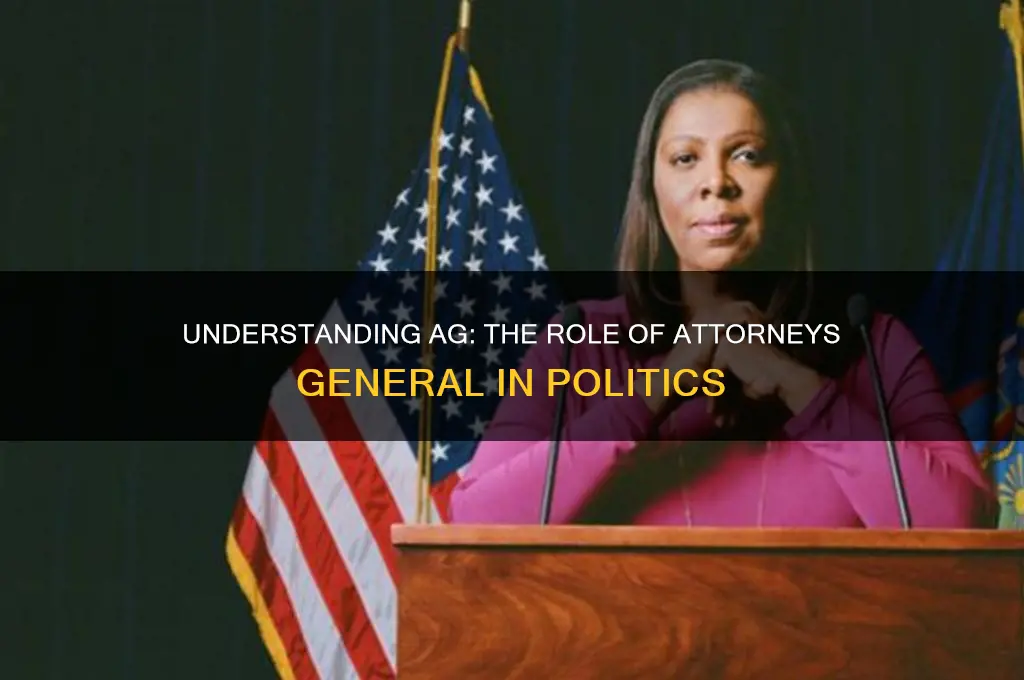

AG in politics typically refers to the Attorney General, a key legal and political figure in many countries, particularly in the United States. The Attorney General serves as the chief legal advisor to the government and is responsible for overseeing the enforcement of laws and representing the state in legal matters. In the U.S., the Attorney General heads the Department of Justice and plays a crucial role in shaping national policies on issues such as civil rights, criminal justice, and national security. The position is both a legal and political role, often influencing the administration’s agenda and responding to broader societal concerns. Understanding the role of the AG is essential for grasping the intersection of law and politics in governance.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Agricultural Policy Influence: How farming interests shape political decisions and legislation

- Rural vs. Urban Politics: The divide in political priorities between rural and urban areas

- Farm Subsidies Debate: Political discussions on government financial support for agricultural producers

- Agribusiness Lobbying: Corporate agriculture's role in influencing political agendas and policies

- Environmental Ag Policies: Political actions addressing agriculture's impact on climate and ecosystems

Agricultural Policy Influence: How farming interests shape political decisions and legislation

Agricultural interests wield significant power in shaping political decisions and legislation, often driving policies that favor specific farming sectors over broader societal or environmental goals. For instance, in the United States, the Farm Bill, reauthorized every five years, allocates billions of dollars in subsidies, insurance, and conservation programs. These funds disproportionately benefit large-scale commodity crop producers (e.g., corn, soy, wheat) over small family farms or specialty crops. This imbalance is no accident—it reflects the lobbying strength of agribusiness giants and commodity groups, who advocate for policies that maximize their profitability, even if it distorts markets or harms environmental sustainability.

Consider the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which consumes nearly 40% of the EU budget. While originally designed to ensure food security and stabilize farmer incomes, CAP has evolved into a complex system that often rewards land ownership over sustainable practices. For example, direct payments are tied to hectares farmed, incentivizing land consolidation and intensification. This structure marginalizes smallholder farmers and perpetuates environmental degradation, such as soil erosion and biodiversity loss. Reforms to CAP have been slow, partly because agricultural lobbies effectively resist changes that might reduce their financial benefits, even when those changes align with public interests like climate resilience or rural development.

To understand how farming interests influence policy, examine the role of campaign contributions and lobbying. In the 2020 U.S. election cycle, the agricultural sector contributed over $100 million to federal candidates and political action committees, with a focus on key committees like the House and Senate Agriculture Committees. These contributions often correlate with favorable legislative outcomes, such as weakened environmental regulations or expanded crop insurance subsidies. Similarly, in Brazil, the "ruralist bloc," a coalition of agribusiness interests, holds significant sway in Congress, pushing policies that accelerate deforestation in the Amazon to expand soybean and cattle production. This political clout underscores how financial resources translate into policy leverage, often at the expense of long-term ecological and social well-being.

A comparative analysis of agricultural policies in Japan and India highlights how cultural and economic factors intersect with political influence. Japan’s rice subsidies, rooted in historical food security concerns, have created a system where rice farmers receive price supports far above global market rates. This policy, driven by the political power of rural constituencies, has stifled agricultural diversification and contributed to inefficiencies. In contrast, India’s Minimum Support Price (MSP) system for crops like wheat and rice aims to protect smallholder farmers but often benefits wealthier farmers with greater access to resources. Both cases demonstrate how agricultural policies, shaped by domestic political pressures, can entrench inequities and hinder broader agricultural modernization.

To mitigate the outsized influence of farming interests, policymakers and advocates can adopt several strategies. First, increase transparency in lobbying and campaign financing to expose conflicts of interest. Second, prioritize evidence-based policymaking that balances agricultural productivity with environmental and social goals. For example, incentivizing regenerative farming practices through targeted subsidies can improve soil health and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Third, amplify the voices of underrepresented stakeholders, such as smallholder farmers, rural communities, and environmental groups, in policy discussions. By diversifying the policy-making process, governments can ensure that agricultural policies serve the public good rather than narrow sectoral interests.

Understanding Political Thuggery: Tactics, Impact, and Global Implications

You may want to see also

Rural vs. Urban Politics: The divide in political priorities between rural and urban areas

The political landscape is often a battleground of contrasting priorities, and the divide between rural and urban areas is a stark example of this. In the context of 'AG' or agricultural politics, this rift becomes even more pronounced, as the needs and concerns of farmers and rural communities clash with those of city dwellers.

The Rural Perspective: A Focus on Agricultural Sustainability

In rural areas, politics is intimately tied to the land and its produce. Farmers and rural residents prioritize policies that support agricultural sustainability, such as subsidies for crop insurance, investment in rural infrastructure, and initiatives to combat climate change's impact on farming. For instance, in the United States, the Farm Bill, reauthorized every five years, is a critical piece of legislation that addresses agricultural and food policy, including conservation, rural development, and nutrition assistance. Rural voters often advocate for measures that ensure fair prices for their crops, access to global markets, and protection against unpredictable weather patterns. A 2020 study by the University of Missouri found that rural voters were more likely to support candidates who prioritized agricultural research and development, with 63% of respondents citing this as a key issue.

Urban Priorities: A Shift towards Environmental and Social Concerns

In contrast, urban politics often emphasizes environmental sustainability, social justice, and economic growth. City dwellers may prioritize policies that address air and water quality, public transportation, and affordable housing. While urban voters may support agricultural initiatives, their focus tends to be on the environmental and social implications of farming practices, such as pesticide use, water consumption, and labor conditions. For example, a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2019 revealed that 78% of urban residents in the European Union considered environmental protection a top priority, compared to 65% of rural residents. This disparity highlights the differing concerns between rural and urban populations.

Bridging the Divide: Finding Common Ground

To address the rural-urban political divide, policymakers must identify areas of common ground. One approach is to promote initiatives that benefit both rural and urban communities, such as investing in renewable energy projects that create jobs in rural areas while reducing urban carbon footprints. Another strategy is to foster dialogue and collaboration between rural and urban stakeholders, ensuring that agricultural policies consider the needs of both groups. For instance, the development of farmers' markets and community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs can provide rural farmers with direct access to urban consumers, while also addressing urban food security concerns.

Practical Steps towards Reconciliation

- Encourage cross-sector partnerships: Facilitate collaborations between rural agricultural organizations and urban environmental groups to develop mutually beneficial solutions.

- Invest in rural broadband infrastructure: Expand high-speed internet access to rural areas, enabling farmers to access online markets, educational resources, and precision agriculture technologies.

- Promote agricultural education in urban areas: Integrate farming and food systems education into urban school curricula to raise awareness about the importance of agriculture and foster empathy for rural communities.

- Support rural-urban exchange programs: Create opportunities for rural and urban residents to visit and learn from each other's communities, fostering understanding and appreciation for their respective priorities.

By acknowledging and addressing the unique needs of both rural and urban populations, policymakers can work towards a more inclusive and equitable agricultural policy framework. This approach not only bridges the rural-urban divide but also ensures that the voices of farmers and rural communities are heard and valued in the broader political discourse. As the global population continues to urbanize, finding common ground between rural and urban priorities will be essential for creating a sustainable and resilient food system.

Understanding Gilded Age Politics: Corruption, Industrialism, and Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Farm Subsidies Debate: Political discussions on government financial support for agricultural producers

Farm subsidies, a cornerstone of agricultural policy in many countries, spark intense political debates that pit economic efficiency against social equity. At their core, these subsidies are government payments or incentives designed to support farmers, stabilize food prices, and ensure national food security. However, their implementation often reveals a complex web of winners and losers, making them a lightning rod for political contention. Proponents argue that subsidies safeguard rural livelihoods, protect against market volatility, and maintain a domestic food supply. Critics, however, contend that they distort markets, disproportionately benefit large agribusinesses, and strain public finances. This tension is particularly evident in the United States, where the Farm Bill, reauthorized every five years, becomes a battleground for competing interests, from small family farms to multinational corporations.

Consider the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which allocates nearly 40% of its budget to agricultural subsidies. While it has historically aimed to support farmers and rural development, it has also faced criticism for overproduction, environmental degradation, and inequitable distribution. Smallholder farmers often receive a fraction of the benefits compared to larger operations, raising questions about fairness and efficiency. Similarly, in India, subsidies for fertilizers, water, and electricity have led to groundwater depletion and soil degradation, highlighting the unintended consequences of well-intentioned policies. These examples underscore the need for a nuanced approach that balances immediate economic support with long-term sustainability.

Politically, farm subsidies are often framed as a moral imperative to protect the "heartland" or rural communities, which carry significant cultural and electoral weight. In the U.S., for instance, agricultural states wield considerable influence in Congress, ensuring that subsidies remain a priority despite their cost. This dynamic creates a paradox: while subsidies are marketed as a lifeline for struggling farmers, they frequently entrench existing power structures, favoring those with the resources to lobby for their interests. This raises ethical questions about who truly benefits from these policies and whether they align with broader societal goals, such as environmental conservation or equitable food distribution.

To navigate this debate, policymakers must adopt a multi-faceted strategy. First, subsidies should be redesigned to incentivize sustainable practices, such as crop rotation, reduced chemical use, and soil conservation. Second, transparency and accountability mechanisms are essential to ensure funds reach those most in need, rather than being captured by large corporations. Third, diversifying support beyond direct payments—such as investing in rural infrastructure, education, and alternative income streams—can reduce dependency on subsidies while fostering resilience. Finally, international cooperation is crucial to address global market distortions and create a level playing field for farmers worldwide.

In conclusion, the farm subsidies debate is not merely about dollars and crops; it reflects deeper ideological divides over the role of government, the value of rural communities, and the trade-offs between short-term stability and long-term sustainability. By reframing the discussion to prioritize fairness, environmental stewardship, and economic efficiency, policymakers can transform subsidies from a source of contention into a tool for inclusive and sustainable development. The challenge lies in balancing competing interests while ensuring that agricultural policies serve the greater good, both today and for future generations.

Does Politico Support Trump? Analyzing the Media's Stance and Coverage

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$39.54 $100

Agribusiness Lobbying: Corporate agriculture's role in influencing political agendas and policies

Agribusiness lobbying is a powerful force shaping political agendas and policies, often prioritizing corporate interests over public health, environmental sustainability, and small-scale farmers. Consider this: in the U.S. alone, the agricultural sector spent over $120 million on lobbying in 2022, with major players like Monsanto (now Bayer) and Tyson Foods leading the charge. This financial muscle translates into direct influence on legislation, from farm subsidies to food safety regulations. For instance, the 2018 Farm Bill included provisions heavily lobbied for by agribusiness giants, such as reduced restrictions on pesticide use and expanded crop insurance programs that disproportionately benefit large corporations.

To understand the mechanics of this influence, examine the tactics employed by agribusiness lobbyists. They often frame their interests as aligned with national priorities, such as food security or economic growth, while downplaying negative externalities like environmental degradation or labor exploitation. For example, lobbying efforts have successfully delayed or weakened regulations on greenhouse gas emissions from livestock operations, despite their significant contribution to climate change. Additionally, agribusiness groups frequently fund political campaigns and think tanks, creating a symbiotic relationship between corporate agriculture and policymakers. This quid pro quo system ensures that policies remain favorable to industry giants, often at the expense of smaller farmers and consumers.

A comparative analysis reveals that agribusiness lobbying is not unique to the U.S. In the European Union, corporations like Nestlé and Syngenta have similarly shaped policies, such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which allocates billions in subsidies. However, the EU’s stricter transparency rules provide a partial counterbalance, requiring lobbyists to disclose meetings with policymakers. In contrast, U.S. lobbying practices often operate with less oversight, allowing for more covert influence. This disparity highlights the need for global regulatory reforms to level the playing field and ensure policies serve public interests rather than corporate profits.

For those seeking to counteract agribusiness lobbying, practical steps include supporting grassroots organizations advocating for sustainable agriculture and transparent policy-making. Consumers can also vote with their wallets by choosing locally sourced, organic, or fair-trade products, which reduce demand for industrially produced goods. Policymakers, meanwhile, should prioritize campaign finance reform and mandatory lobbying disclosures to minimize corporate influence. By taking these actions, individuals and communities can challenge the dominance of agribusiness in politics and foster a more equitable and sustainable food system.

Ultimately, agribusiness lobbying exemplifies how corporate power can distort political agendas, but it also underscores the potential for collective action to reclaim control. The challenge lies in translating awareness into systemic change, ensuring that agricultural policies prioritize people and the planet over profit.

Is Comparative Politics Too Broad? Exploring Scope and Limitations

You may want to see also

Environmental Ag Policies: Political actions addressing agriculture's impact on climate and ecosystems

Agriculture's environmental footprint is undeniable, contributing significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and water pollution. This reality has spurred the development of Environmental Ag Policies, a critical subset of political actions aimed at mitigating agriculture's impact on climate and ecosystems. These policies are not merely theoretical constructs but practical frameworks designed to balance food production with environmental sustainability.

Consider the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which has evolved to include stringent environmental requirements. Farmers receiving subsidies must comply with "greening measures," such as maintaining ecological focus areas, crop diversification, and preserving permanent grasslands. These measures are not optional; they are mandatory for accessing financial support. For instance, a farmer with 15 hectares of arable land must dedicate at least 5% of this area to ecological focus areas, such as hedgerows or fallow land, to foster biodiversity and reduce soil erosion.

In contrast, California’s Healthy Soils Program takes a more incentive-based approach, offering grants to farmers who implement practices like cover cropping, compost application, and reduced tillage. These practices not only sequester carbon but also improve soil health, leading to more resilient crops. A vineyard in Napa Valley, for example, received a $50,000 grant to apply 2 tons of compost per acre, reducing its carbon footprint while enhancing grape quality. This program underscores the importance of financial incentives in driving behavioral change.

However, implementing such policies is not without challenges. Trade-offs between productivity and sustainability often create friction. Smallholder farmers in developing countries, for instance, may struggle to adopt eco-friendly practices due to limited resources and immediate livelihood concerns. Policies must therefore be context-specific, offering tailored solutions. In India, the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) promotes organic farming by providing financial assistance for certification and training. This program recognizes the dual benefits of reducing chemical inputs and improving farmer incomes, demonstrating how environmental policies can align with socio-economic goals.

Ultimately, the success of Environmental Ag Policies hinges on collaboration and innovation. Governments, farmers, scientists, and consumers must work together to develop scalable solutions. For example, precision agriculture technologies, such as drones and soil sensors, can optimize resource use while minimizing environmental harm. A dairy farm in Wisconsin reduced its water usage by 30% by implementing a sensor-based irrigation system, showcasing the potential of technology to bridge the productivity-sustainability gap.

In conclusion, Environmental Ag Policies are not a one-size-fits-all solution but a dynamic toolkit requiring adaptability and commitment. By integrating mandatory measures, financial incentives, and technological advancements, these policies can transform agriculture from a climate culprit into a steward of the planet. The challenge lies in balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability, ensuring that the policies are equitable, effective, and forward-thinking.

Politically Incorrect Humor: Navigating the Fine Line Between Comedy and Offense

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

AG stands for Attorney General, a chief legal advisor and law enforcement officer in many jurisdictions, including the United States.

An AG is responsible for representing the government in legal matters, enforcing laws, providing legal advice to the executive branch, and often overseeing state or federal law enforcement agencies.

It varies by jurisdiction. In the U.S., the state AG is typically elected, while the U.S. Attorney General is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

A state AG handles legal matters within their state, while the U.S. AG oversees federal law enforcement and represents the federal government in legal cases.

Yes, an AG has the authority to prosecute violations of laws within their jurisdiction, whether at the state or federal level, and can initiate legal action against individuals, corporations, or government entities.

![New Development of local government agricultural policy (2011) ISBN: 4880375748 [Japanese Import]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51gO1Fe8p1L._AC_UY218_.jpg)