Redline politics refers to policies or practices that create or reinforce systemic inequalities, often along racial, economic, or social lines. The term draws its name from the historical practice of redlining, where banks and government entities would deny services or investment to neighborhoods based on the racial or ethnic composition of their residents, typically marking these areas in red on maps. In contemporary discourse, redline politics encompasses a broader range of issues, including discriminatory housing policies, unequal access to education and healthcare, and systemic barriers that perpetuate disparities. Understanding redline politics is crucial for addressing the root causes of inequality and advocating for policies that promote equity and justice.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Redlining: Historical practice of denying services or increasing costs based on racial demographics

- Origins in Housing: Started in the 1930s, segregating neighborhoods and limiting minority homeownership

- Economic Impact: Redlining perpetuates wealth gaps and restricts access to loans and investments

- Modern Redlining: Persistent discrimination in lending, insurance, and environmental policies affecting marginalized communities

- Policy Reforms: Efforts to address redlining through fair housing laws and community reinvestment acts

Definition of Redlining: Historical practice of denying services or increasing costs based on racial demographics

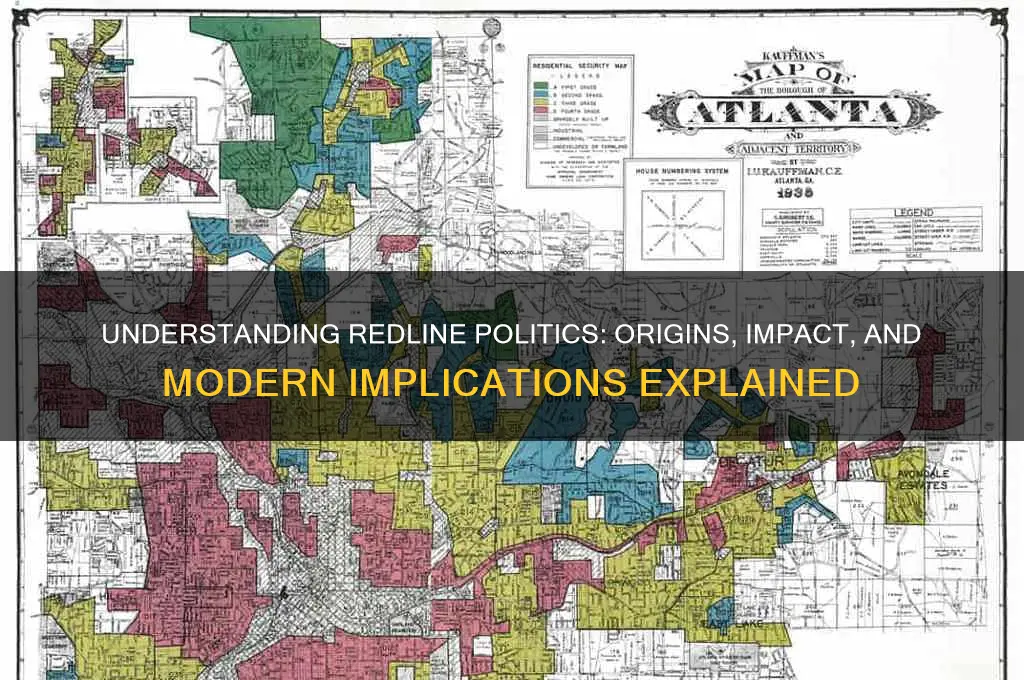

Redlining, a term etched into the annals of American history, refers to the systematic denial of services or the imposition of higher costs on communities based on racial and ethnic demographics. This practice, which gained prominence in the early 20th century, was institutionalized through the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps, which color-coded neighborhoods to indicate their creditworthiness. Areas with significant African American, Hispanic, or immigrant populations were outlined in red, labeling them as hazardous for investment. This visual representation became the literal and metaphorical redline, segregating communities and perpetuating racial inequality.

The mechanics of redlining were insidious, operating through banks, insurance companies, and government agencies. For instance, residents in redlined areas faced outright denial of mortgage loans, making homeownership—a cornerstone of wealth accumulation—inaccessible. Those who did secure loans often paid exorbitant interest rates, sometimes double the national average. This financial exclusion was not limited to housing; it extended to business loans, insurance policies, and even access to supermarkets and healthcare facilities. The cumulative effect was a cycle of poverty and disinvestment that trapped generations in marginalized neighborhoods.

To understand the long-term impact, consider the wealth gap between white and Black households in the United States. As of 2023, the median wealth for white families is nearly ten times that of Black families, a disparity rooted in decades of redlining. Neighborhoods once redlined in the 1930s remain underresourced today, with lower property values, fewer schools, and higher crime rates. This historical practice did not merely deny services; it engineered a geography of inequality that continues to shape urban landscapes and social mobility.

While redlining was officially outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, its legacy persists through modern practices like predatory lending and algorithmic bias. For example, studies show that people of color are still more likely to be denied mortgages or offered higher interest rates, even when controlling for income and creditworthiness. To combat this, policymakers and advocates must focus on reparative measures, such as community reinvestment programs and affordable housing initiatives. Individuals can contribute by supporting organizations that audit financial institutions for discriminatory practices and by educating themselves on the history of redlining to recognize its contemporary manifestations.

In essence, redlining was not just a policy but a tool of racial engineering that reshaped the economic and social fabric of America. Its definition extends beyond historical denial of services to encompass the systemic barriers it erected, which continue to influence opportunities for marginalized communities. Addressing its legacy requires both acknowledgment of its roots and proactive efforts to dismantle the structures it created. Without this, the redline will remain a dividing force, perpetuating inequities for generations to come.

Mastering Political Advocacy: Strategies for Effective Change and Influence

You may want to see also

Origins in Housing: Started in the 1930s, segregating neighborhoods and limiting minority homeownership

The roots of redlining trace back to the 1930s, when the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) introduced color-coded maps to assess mortgage risk. These maps systematically labeled minority neighborhoods—particularly Black and immigrant communities—as "hazardous" or "declining," effectively denying residents access to federally backed loans. This practice wasn’t just discriminatory; it was institutionalized, creating a blueprint for racial segregation in housing that persists in subtle forms today.

Consider the mechanics of this system: HOLC appraisers evaluated neighborhoods based on factors like race, ethnicity, and perceived "desirability." Areas with higher minority populations were redlined, marked in red to signify high risk. This designation starved these neighborhoods of investment, limiting homeownership opportunities for minorities and trapping them in cycles of poverty. Meanwhile, white neighborhoods were greenlined, receiving favorable loans that fueled wealth accumulation and suburban expansion.

The consequences were profound and far-reaching. Redlined neighborhoods faced disinvestment, leading to deteriorating infrastructure, limited access to quality schools, and higher crime rates. Conversely, greenlined areas thrived, with property values soaring and residents building generational wealth through home equity. This disparity wasn’t accidental—it was a deliberate policy choice that cemented racial divides in American cities.

To understand the legacy of redlining, examine modern-day housing patterns. Studies show that historically redlined neighborhoods remain predominantly minority and low-income, with lower homeownership rates and higher rates of foreclosure. For instance, a 2018 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that 74% of neighborhoods redlined in the 1930s are still struggling economically today. This isn’t merely history; it’s a living, breathing consequence of policies designed to exclude.

Addressing this legacy requires targeted interventions. Policymakers can implement programs like community land trusts, which provide affordable housing options in formerly redlined areas. Financial institutions should also expand lending to minority borrowers, offering fair terms and eliminating predatory practices. Individuals can contribute by supporting local initiatives that promote equitable development and advocating for policies that dismantle systemic barriers to homeownership. The fight against redlining’s legacy isn’t just about correcting past wrongs—it’s about building a future where housing is a right, not a privilege.

Sam Stein's Departure from Politico: What Really Happened?

You may want to see also

Economic Impact: Redlining perpetuates wealth gaps and restricts access to loans and investments

Redlining, a discriminatory practice rooted in the 1930s, continues to cast a long shadow over economic opportunities for marginalized communities, particularly Black and minority neighborhoods. By systematically denying these areas access to loans, investments, and financial services, redlining has entrenched wealth disparities that persist generations later. The Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA) color-coded maps, which labeled minority neighborhoods as "hazardous" for investment, explicitly excluded these communities from the post-WWII housing boom, a period that significantly expanded the American middle class. This exclusion was not merely a historical footnote; it was a deliberate policy that denied families the chance to build intergenerational wealth through homeownership, a primary vehicle for asset accumulation in the U.S.

Consider the mechanics of this economic disenfranchisement. When banks and lenders refuse to extend mortgages or business loans to residents of redlined areas, they effectively stifle local economic growth. Without capital, small businesses struggle to open or expand, jobs remain scarce, and property values stagnate. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of poverty, as residents are unable to access the financial tools necessary to improve their economic standing. For instance, a 2018 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that three out of four neighborhoods redlined in the 1930s remain low-to-moderate income areas today, underscoring the enduring impact of these policies.

The consequences of redlining extend beyond individual households to shape broader economic landscapes. Communities denied access to capital often lack the resources to invest in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, further limiting their potential for growth. This systemic underinvestment not only harms residents but also deprives the broader economy of the contributions these communities could make if given equitable opportunities. For example, a 2020 report by McKinsey & Company estimated that closing racial wealth gaps could add $1.5 trillion to the U.S. GDP by 2028, highlighting the economic cost of perpetuating these disparities.

Addressing the economic impact of redlining requires targeted interventions that go beyond symbolic gestures. Policymakers and financial institutions must prioritize initiatives such as community reinvestment programs, affordable housing developments, and small business grants in historically redlined areas. Additionally, implementing stricter fair lending laws and increasing transparency in lending practices can help dismantle the barriers that continue to exclude marginalized communities from economic participation. By taking these steps, we can begin to reverse the damage caused by redlining and move toward a more equitable economic future.

Ultimately, the economic impact of redlining is a stark reminder of how discriminatory policies can create lasting divides. It is not enough to acknowledge this history; we must actively work to undo its legacy. This means not only addressing the immediate financial needs of affected communities but also fostering an environment where wealth-building opportunities are accessible to all. Only then can we hope to close the wealth gaps that redlining has so profoundly widened.

Understanding Open Access (OA) and Its Impact on Political Transparency

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern Redlining: Persistent discrimination in lending, insurance, and environmental policies affecting marginalized communities

The practice of redlining, born in the 1930s, mapped racial demographics to deny services like loans and insurance to predominantly Black and immigrant neighborhoods. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed this explicit discrimination in 1968, its legacy persists in subtler, yet equally damaging, forms. Today, "modern redlining" manifests in algorithmic biases, predatory lending practices, and environmental policies that disproportionately burden marginalized communities.

A 2022 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that Black and Latino borrowers are still 80% more likely to be denied mortgages than white borrowers, even when controlling for income and creditworthiness. This isn't simply a relic of the past; it's a systemic issue perpetuated by data-driven algorithms trained on historically biased data, effectively codifying discrimination into the digital age.

Consider the case of auto insurance. Algorithms used by major insurers often factor in zip codes, a proxy for race and ethnicity, leading to higher premiums for residents of predominantly minority neighborhoods. This "digital redlining" traps individuals in a cycle of financial disadvantage, limiting their ability to build wealth and access opportunities. Similarly, environmental policies often prioritize development in wealthier, whiter areas, while relegating hazardous waste facilities, polluting industries, and infrastructure projects to marginalized communities. This "environmental racism" exposes residents to higher rates of asthma, cancer, and other health issues, further exacerbating existing inequalities.

Imagine a predominantly Black neighborhood bordering a busy highway. The constant noise and air pollution contribute to higher rates of respiratory illnesses among residents. Meanwhile, a wealthier, predominantly white neighborhood enjoys a lush green space and cleaner air. This isn't a coincidence; it's a direct result of policies that prioritize profit over people, perpetuating a cycle of environmental injustice.

Breaking the cycle of modern redlining requires a multi-pronged approach. Firstly, we need robust regulations to combat algorithmic bias and ensure transparency in lending and insurance practices. Secondly, we must invest in community development initiatives that empower marginalized neighborhoods, providing access to affordable housing, quality education, and healthcare. Finally, we need to hold policymakers accountable for environmental justice, ensuring that all communities, regardless of race or income, have access to clean air, water, and safe living environments. Only by addressing these systemic inequalities can we truly dismantle the legacy of redlining and build a more just and equitable society.

Understanding Political Self-Preservation: Tactics, Motivations, and Real-World Implications

You may want to see also

Policy Reforms: Efforts to address redlining through fair housing laws and community reinvestment acts

Redlining, a discriminatory practice rooted in the 1930s, systematically denied services and investment to minority neighborhoods, entrenching racial and economic disparities. Policy reforms, particularly through fair housing laws and community reinvestment acts, have emerged as critical tools to dismantle this legacy. The Fair Housing Act of 1968, enacted in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, prohibits discrimination in housing based on race, color, religion, sex, familial status, national origin, and disability. While a foundational step, its enforcement has been inconsistent, highlighting the need for complementary measures.

One such measure is the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977, designed to encourage banks to meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. By evaluating banks’ lending practices and requiring them to reinvest in underserved areas, the CRA aims to reverse the effects of redlining. However, critics argue that compliance often results in superficial investments rather than transformative change. For instance, banks may fulfill CRA requirements through loans that do not address systemic issues like affordable housing shortages or economic stagnation.

To strengthen these efforts, policymakers have introduced targeted amendments and programs. The Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule, implemented under the Obama administration, required jurisdictions to actively identify and address barriers to fair housing. While the rule was rolled back in 2020, its framework remains a model for proactive policy. Similarly, local initiatives, such as inclusionary zoning and housing trust funds, have been adopted to ensure affordable housing development in historically redlined areas. These measures, while promising, require robust funding and political will to achieve meaningful impact.

A comparative analysis reveals that while fair housing laws and the CRA provide a legal and financial framework, their effectiveness hinges on rigorous enforcement and community engagement. For example, cities like Minneapolis have adopted policies that mandate affordable housing units in new developments, directly countering segregation. Conversely, areas with weak enforcement mechanisms continue to struggle with disparities. Practical tips for advocates include leveraging data to identify redlining hotspots, partnering with community organizations to amplify voices, and pushing for transparency in bank lending practices.

Ultimately, addressing redlining through policy reforms demands a multi-faceted approach. Fair housing laws and the CRA are essential but insufficient on their own. By integrating targeted amendments, local initiatives, and community-driven strategies, policymakers can begin to dismantle the systemic barriers created by redlining. The challenge lies not in the absence of tools but in the consistent and equitable application of these measures to foster inclusive growth.

Technology's Impact: Does Digital Advancement Threaten Political Stability?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

"Redline politics" typically refers to policies or practices that create or reinforce racial or socioeconomic boundaries, often through discriminatory actions like redlining in housing, which historically denied services or opportunities to specific communities based on race or ethnicity.

Redline politics continues to impact modern society by perpetuating systemic inequalities, such as disparities in wealth, education, and access to resources, which stem from historical practices that marginalized certain racial or socioeconomic groups.

Examples include discriminatory lending practices, gerrymandering, environmental racism (e.g., placing pollutants in minority neighborhoods), and policies that disproportionately affect low-income or minority communities, such as voter suppression or unequal access to healthcare.