Political parties play a crucial role in democratic systems by aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and facilitating governance. However, one possible weakness of political parties is their tendency to prioritize partisan interests over the broader public good. This can manifest in several ways, such as engaging in divisive rhetoric to secure electoral victories, obstructing bipartisan cooperation on critical issues, or focusing on short-term political gains rather than long-term policy solutions. Additionally, the internal dynamics of parties, including factionalism and the influence of special interests, can further undermine their effectiveness in representing the diverse needs of the electorate. These weaknesses often lead to political polarization, gridlock, and a decline in public trust in democratic institutions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Internal Division | Factionalism within parties can lead to policy inconsistencies and weakened public trust. |

| Elitism and Disconnect | Parties may prioritize the interests of elites or donors over the general public. |

| Polarization | Parties often contribute to ideological polarization, hindering bipartisan cooperation. |

| Corruption and Scandals | Misuse of power, financial scandals, and unethical behavior erode public confidence. |

| Short-Term Focus | Parties may prioritize winning elections over long-term policy solutions. |

| Lack of Accountability | Weak internal mechanisms can lead to leaders acting without sufficient oversight. |

| Voter Disengagement | Parties may fail to engage younger or marginalized voters, leading to low turnout. |

| Influence of Special Interests | Lobbying and funding from special interest groups can distort policy priorities. |

| Rigid Ideologies | Strict adherence to party ideologies can prevent pragmatic solutions to complex issues. |

| Ineffective Leadership | Poor leadership can lead to strategic mistakes and loss of public support. |

| Lack of Diversity | Parties may fail to represent diverse demographics, leading to exclusionary policies. |

| Over-Reliance on Populism | Parties may exploit populist rhetoric, undermining rational policy-making. |

| Weak Grassroots Engagement | Limited involvement of local communities can reduce party legitimacy and effectiveness. |

| Global Influence Challenges | Parties may struggle to address global issues like climate change due to national focus. |

| Technological Lag | Failure to adapt to digital campaigning can reduce outreach and engagement. |

| Electoral System Constraints | First-past-the-post systems can marginalize smaller parties, limiting political diversity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Over-reliance on fundraising: Parties may prioritize wealthy donors over public interests, skewing policies

- Internal factions: Divides within parties can hinder unity and effective governance

- Short-term focus: Parties often prioritize election wins over long-term solutions

- Polarization: Parties may exacerbate divisions, leading to gridlock and extremism

- Lack of accountability: Weak internal mechanisms can allow corruption or incompetence to persist

Over-reliance on fundraising: Parties may prioritize wealthy donors over public interests, skewing policies

Political parties often find themselves in a precarious dance with money, where the rhythm is dictated by the depth of donors' pockets rather than the pulse of public opinion. This over-reliance on fundraising can lead to a dangerous prioritization of wealthy contributors over the broader public interest, skewing policies in favor of those who can afford to influence them. For instance, in the United States, the Citizens United v. FEC decision in 2010 allowed corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns, significantly amplifying the voices of the affluent. This shift has resulted in policies that disproportionately benefit the wealthy, such as tax cuts for high-income earners and deregulation of industries, while often neglecting the needs of the middle and lower classes.

Consider the mechanics of this dynamic: when a political party becomes heavily dependent on large donations, it inadvertently creates a system where access and influence are commodities. Wealthy donors gain privileged access to policymakers, shaping agendas through private meetings, exclusive events, and behind-the-scenes lobbying. This access can lead to policies that favor specific industries or individuals, such as subsidies for corporations or favorable trade agreements, at the expense of broader societal welfare. For example, pharmaceutical companies that contribute significantly to political campaigns often see policies that protect high drug prices, making essential medications less accessible to the general public.

To mitigate this issue, parties must adopt transparent fundraising practices and diversify their revenue sources. One practical step is to implement strict donation caps and require real-time disclosure of contributions. Additionally, parties can explore alternative funding models, such as small-dollar donations from a broader base of supporters or public financing options. Countries like Germany and Canada have successfully integrated public funding into their political systems, reducing the influence of wealthy donors and aligning policies more closely with public interests. By doing so, parties can reclaim their role as representatives of the people rather than proxies for the affluent.

However, transitioning away from over-reliance on fundraising is not without challenges. Parties may fear losing competitive edge in elections, as well-funded campaigns often correlate with electoral success. To address this, policymakers must design reforms that level the playing field, ensuring that all candidates, regardless of funding, have a fair chance to engage with voters. This could include free airtime for candidates on public media, stricter regulations on campaign spending, and penalties for undisclosed or excessive donations. Public education campaigns can also play a role, encouraging citizens to support candidates who prioritize transparency and accountability over big-money influence.

Ultimately, the over-reliance on fundraising is a systemic issue that undermines the democratic process. It distorts policy priorities, erodes public trust, and perpetuates inequality. By acknowledging this weakness and taking proactive steps to address it, political parties can restore their legitimacy and better serve the interests of all citizens. The challenge lies not just in recognizing the problem but in summoning the political will to enact meaningful change. Without such reforms, the voices of the wealthy will continue to drown out those of the many, leaving democracy itself at stake.

Do Political Parties Shape Voter Eligibility Criteria and Qualifications?

You may want to see also

Internal factions: Divides within parties can hinder unity and effective governance

Political parties, often seen as monolithic entities, are in reality complex organisms teeming with internal diversity. This diversity, while a strength in theory, can manifest as a significant weakness when it solidifies into factions. These factions, driven by differing ideologies, personal ambitions, or regional interests, create fault lines within the party structure, hindering unity and ultimately, effective governance.

Imagine a party platform as a carefully woven tapestry. Each thread represents a constituency, an interest group, or a policy stance. Factions act like loose threads, pulling in different directions, threatening to unravel the entire fabric. This internal discord translates into legislative gridlock, inconsistent policy implementation, and a weakened ability to respond to crises.

Consider the recent history of the Republican Party in the United States. The rise of the Tea Party movement within the GOP exemplifies the disruptive power of factions. While sharing a broad conservative ideology, Tea Party adherents prioritized fiscal austerity and smaller government to an extent that often clashed with the more establishment wing of the party. This internal divide led to legislative stalemates, government shutdowns, and a perception of the party as more interested in ideological purity than pragmatic solutions.

The consequences of factionalism extend beyond legislative paralysis. They erode public trust. When a party presents a fractured front, voters perceive weakness and indecisiveness. This undermines the party's legitimacy and can lead to electoral losses. Furthermore, factions can prioritize their narrow interests over the broader national good, resulting in policies that benefit specific groups at the expense of the wider population.

The challenge lies in managing this inherent tension between unity and diversity. Parties must foster internal dialogue and compromise while respecting differing viewpoints. This requires strong leadership capable of bridging divides, inclusive decision-making processes, and a shared commitment to the party's core principles. Without these mechanisms, internal factions will continue to be a significant weakness, undermining the effectiveness and public trust in political parties.

Hillary Clinton's Political Future: Will She Remain in the Arena?

You may want to see also

Short-term focus: Parties often prioritize election wins over long-term solutions

Political parties, by their very nature, are often caught in the cyclical rhythm of election seasons, which can lead to a myopic focus on short-term gains. This phenomenon is not merely a theoretical concern but a practical reality that manifests in various ways. For instance, parties may propose policies that offer immediate relief or gratification to voters, such as tax cuts or increased social spending, without adequately addressing the long-term fiscal sustainability of such measures. The allure of securing votes in the next election frequently overshadows the need to implement structural reforms that might take years or even decades to yield visible results.

Consider the example of environmental policy. While scientists and experts emphasize the urgency of reducing carbon emissions to combat climate change, political parties often hesitate to endorse stringent measures that could alienate voters in the short term. Instead, they might opt for less ambitious, more palatable policies that provide temporary relief but fail to address the root causes of the problem. This short-term focus not only undermines the effectiveness of environmental efforts but also perpetuates a cycle of crisis management rather than proactive governance.

To illustrate further, imagine a political party proposing a temporary reduction in fuel taxes to ease the burden on consumers facing high gas prices. While this move may win favor with voters in the immediate term, it does little to encourage the transition to renewable energy sources or reduce dependency on fossil fuels. Such policies, though politically expedient, often come at the expense of long-term environmental and economic stability. This trade-off highlights the inherent tension between the electoral incentives of political parties and the broader, enduring needs of society.

Addressing this weakness requires a shift in both political culture and institutional design. One practical step is to incentivize long-term thinking through mechanisms like multi-year budgeting or independent commissions tasked with developing policies that transcend electoral cycles. For example, countries like Sweden and New Zealand have experimented with fiscal responsibility laws that mandate balanced budgets over a rolling period, forcing parties to consider the long-term implications of their spending decisions. Additionally, voters can play a role by demanding accountability and rewarding parties that prioritize sustainable solutions over quick fixes.

Ultimately, the short-term focus of political parties is not an insurmountable challenge but a systemic issue that demands deliberate action. By fostering a culture of long-term planning, implementing structural reforms, and holding parties accountable for their promises, societies can mitigate this weakness. The goal is not to eliminate the competitive nature of elections but to ensure that the pursuit of power does not come at the expense of future generations. As citizens and stakeholders, we must advocate for policies that balance immediate needs with long-term prosperity, recognizing that the health of our democracies depends on this delicate equilibrium.

The South's Political Affiliation During the American Civil War Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

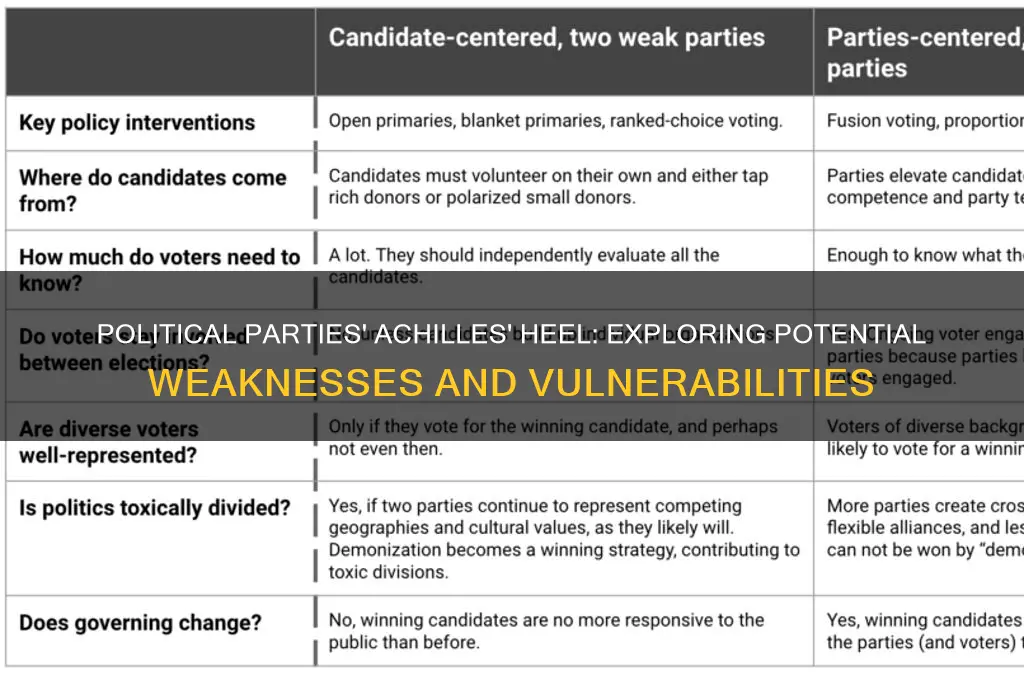

Polarization: Parties may exacerbate divisions, leading to gridlock and extremism

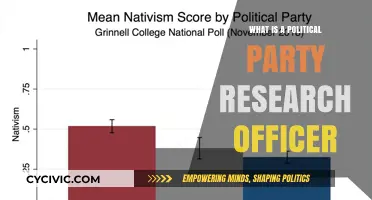

Polarization within political parties often manifests as a deepening ideological divide, where compromise becomes a dirty word. Consider the U.S. Congress, where partisan loyalty frequently trumps problem-solving. A 2021 Pew Research Center study found that 90% of Republicans are more conservative than the median Democrat, and 97% of Democrats are more liberal than the median Republican. This ideological sorting creates an environment where collaboration is rare, and legislation stalls. For instance, the 2013 government shutdown occurred because neither party was willing to budge on funding for the Affordable Care Act, illustrating how polarization can lead to gridlock that harms governance and public trust.

To understand the mechanics of polarization, imagine a feedback loop: parties adopt extreme positions to appeal to their base, which in turn radicalizes the base further. Social media amplifies this effect by creating echo chambers where voters are exposed only to information that confirms their existing beliefs. A study by the Knight Foundation revealed that 64% of Americans believe social media platforms exacerbate political divisions. This dynamic is not unique to the U States; in countries like Brazil and India, parties have increasingly relied on divisive rhetoric to solidify their support, often at the expense of national unity. The takeaway? Polarization is self-reinforcing, making it harder to reverse once it takes hold.

Breaking the cycle of polarization requires deliberate action. One practical step is to reform primary election systems, which often incentivize candidates to cater to the most extreme factions of their party. Implementing open primaries or ranked-choice voting could encourage candidates to appeal to a broader electorate. Additionally, policymakers should address the role of media in polarization by promoting diverse news sources and media literacy programs. For example, Finland’s comprehensive media literacy curriculum has been credited with reducing the spread of misinformation and fostering a more informed citizenry. These measures, while not a panacea, can help mitigate the divisive tendencies of political parties.

Finally, consider the human cost of polarization. When parties prioritize ideological purity over governance, real people suffer. Delayed legislation on issues like healthcare, climate change, or economic relief can have life-altering consequences. For instance, the inability of the U.S. Congress to pass comprehensive gun control legislation, despite widespread public support, reflects the paralyzing effects of polarization. By focusing on what divides us rather than what unites us, political parties risk alienating the very citizens they are meant to serve. The challenge is clear: to rebuild trust and functionality, parties must find ways to bridge the divides they have helped create.

Georgia's Political Landscape: Exploring the Three Largest Parties

You may want to see also

Lack of accountability: Weak internal mechanisms can allow corruption or incompetence to persist

Political parties, as pillars of democratic systems, often struggle with internal accountability, creating fertile ground for corruption and incompetence. Consider the case of a party where leaders are elected through opaque processes, shielded from scrutiny by loyal factions. Without transparent mechanisms for oversight, these leaders can misuse funds, favor cronies, or make decisions that benefit themselves over the public. For instance, in some parties, financial audits are conducted by insiders, allowing embezzlement to go undetected for years. This lack of transparency erodes public trust and undermines the party’s legitimacy.

To address this, parties must adopt robust accountability frameworks. Start by establishing independent ethics committees with external members, such as legal experts or civil society representatives. These committees should have the authority to investigate allegations of misconduct and impose penalties, including expulsion. Additionally, mandatory public disclosure of party finances, including donations and expenditures, can deter corruption. For example, countries like Germany require political parties to submit detailed financial reports, which are audited by non-partisan bodies and made accessible to citizens. Implementing such measures ensures that leaders are held to high standards and reduces the risk of malfeasance.

However, creating accountability mechanisms is only the first step; enforcing them is equally critical. Parties often resist internal reforms due to power dynamics, where influential members fear losing control. To overcome this, incentivize compliance by tying accountability measures to public funding or electoral support. For instance, parties that fail to meet transparency standards could face reduced state subsidies or be barred from receiving corporate donations. This approach not only encourages adherence but also signals to voters that the party is committed to integrity.

A comparative analysis reveals that parties with strong internal accountability tend to perform better electorally and maintain higher public approval. Take the example of Sweden’s Social Democratic Party, which has long emphasized transparency and ethical governance, contributing to its enduring popularity. Conversely, parties plagued by scandals, like Brazil’s Workers’ Party during the Petrobras corruption case, often face significant electoral backlash. The takeaway is clear: accountability is not just a moral imperative but a strategic necessity for long-term success.

Finally, fostering a culture of accountability requires proactive engagement from party members at all levels. Encourage grassroots participation in decision-making processes, such as through open primaries or digital platforms for policy feedback. Educate members about the importance of integrity and provide training on identifying and reporting unethical behavior. By empowering individuals to act as watchdogs, parties can create a self-regulating environment that minimizes the risk of corruption and incompetence. In essence, accountability is a collective responsibility that strengthens the party from within and reinforces its role as a trustworthy democratic actor.

Farmers' Allies: Which Political Party Championed Agricultural Interests?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A possible weakness is internal division, where differing factions within a party prioritize their own agendas over unity, leading to ineffectiveness and reduced public trust.

A possible weakness is the tendency to prioritize the interests of dominant groups or donors, marginalizing minority or less influential voices within the electorate.

A possible weakness is ideological rigidity, where parties adhere strictly to their platforms, hindering compromise and preventing practical solutions to complex issues.

A possible weakness is the lack of transparency and accountability, as parties may prioritize staying in power over fulfilling campaign promises or addressing public needs.

A possible weakness is their role in deepening political polarization by focusing on partisan rhetoric and divisive tactics, which can undermine constructive dialogue and national unity.