Political religion is a concept that describes the ways in which political ideologies and systems can adopt the characteristics of religion, such as absolute devotion, sacred symbols, rituals, and a moral framework that defines good and evil. Coined by scholars like Emilio Gentile and Hans Maier, it highlights how certain political movements, such as fascism, communism, and nationalism, can function as secular religions, demanding unwavering loyalty and shaping collective identities. These ideologies often replace traditional religious beliefs with a new set of dogmas centered around the state, a leader, or a utopian vision, fostering a sense of purpose and belonging while marginalizing dissent. By examining political religion, we gain insight into how politics can transcend its practical role to become a deeply emotional and spiritual force in society.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

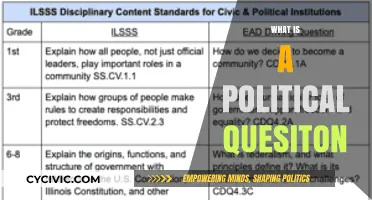

- Definition and Origins: Coined by Voegelin, describes ideologies replacing religion with political dogma and symbols

- Key Characteristics: Totalitarianism, sacred narratives, cult of personality, and absolute loyalty

- Historical Examples: Fascism, Communism, and extreme nationalism as political religion manifestations

- Role of Propaganda: Manipulates beliefs, shapes identity, and enforces conformity through media and education

- Criticism and Debate: Challenges its validity as a concept and its applicability to modern politics

Definition and Origins: Coined by Voegelin, describes ideologies replacing religion with political dogma and symbols

The concept of political religion, as coined by Eric Voegelin, offers a lens to understand how certain ideologies mimic religious structures, replacing spiritual dogma with political fervor. Voegelin, a political philosopher, observed that modern totalitarian movements—such as Nazism and Stalinism—functioned like religions, complete with sacred texts, rituals, and a messianic vision. These ideologies demanded absolute loyalty, transcending mere policy to become all-encompassing belief systems. By analyzing this phenomenon, Voegelin highlighted the dangers of politicized faith, where the state or party becomes the ultimate authority, and dissent is treated as heresy.

To grasp Voegelin’s definition, consider the structural parallels between religion and political dogma. Religions often feature a transcendent purpose, moral codes, and symbols that unite believers. Similarly, political religions elevate ideological goals—like racial purity or class struggle—to a sacred status. Symbols such as flags, anthems, and leaders become objects of veneration. For instance, Nazi Germany’s swastika and Hitler’s cult of personality mirrored religious iconography and worship. This substitution of political symbols for religious ones creates a new framework for meaning, often at the expense of individual autonomy and critical thought.

Voegelin’s origins of this concept lie in his critique of modernity’s attempt to fill the void left by declining traditional religions. As societies secularized, he argued, they sought new sources of ultimate meaning. Political ideologies stepped into this breach, offering certainty and purpose in an uncertain world. However, unlike traditional religions, which often emphasize transcendence and personal salvation, political religions focus on collective transformation, frequently through coercive means. This shift from spiritual to political salvation explains why such ideologies can inspire both mass mobilization and mass atrocities.

Practical examples illustrate Voegelin’s theory. In Maoist China, the Cultural Revolution turned political loyalty into a religious-like test of faith, with "Little Red Books" serving as sacred texts. Similarly, the Soviet Union’s cult of Lenin and Stalin transformed communism into a quasi-religious movement, complete with pilgrimage sites and martyr narratives. These cases demonstrate how political religions co-opt religious mechanisms to enforce conformity and suppress dissent. Recognizing these patterns is crucial for identifying contemporary movements that may adopt similar tactics, from extremist groups to populist regimes.

In conclusion, Voegelin’s concept of political religion serves as a warning against the dangers of ideologically driven absolutism. By replacing religion with political dogma and symbols, such movements create a new form of orthodoxy that demands total adherence. Understanding this dynamic allows us to critically assess modern ideologies, ensuring they do not devolve into dogmatic systems that undermine freedom and diversity. Voegelin’s framework remains a vital tool for navigating the complex interplay between politics, belief, and power.

Mastering the Art of Graceful Resignation: Tips for Giving Notice Politely

You may want to see also

Key Characteristics: Totalitarianism, sacred narratives, cult of personality, and absolute loyalty

Political religions, though devoid of deities, mirror traditional religions in their demand for absolute devotion and their structuring of society around a singular, unchallengeable truth. Totalitarianism is their bedrock, a system where the state subsumes all aspects of life, leaving no room for dissent or individuality. Consider North Korea, where the Juche ideology permeates every facet of existence, from education to family life, ensuring the state’s supremacy over personal autonomy. This totalizing control is not merely political but spiritual, demanding a surrender of self to the collective will. Unlike liberal democracies, which thrive on pluralism, political religions enforce uniformity through coercion, surveillance, and propaganda, creating a society where the state’s ideology is the only permissible faith.

At the heart of every political religion lies a sacred narrative, a mythologized story that legitimizes its authority and provides a sense of purpose. The Nazi regime, for instance, constructed a narrative of Aryan supremacy and historical destiny, rooted in a distorted interpretation of history and biology. This narrative was not just a political tool but a sacred text, imbued with emotional and symbolic power. Similarly, Maoist China’s "Long March" became a foundational myth, glorifying struggle and sacrifice as the path to revolutionary purity. These narratives serve as moral compasses, guiding followers toward an idealized future while justifying present hardships. They are immutable, beyond critique, and function as the moral and ideological glue binding the faithful to the cause.

No political religion is complete without a cult of personality, elevating a leader to near-divine status. Stalin, Mao, and Kim Il-sung exemplify this phenomenon, their images omnipresent, their words infallible, their lives shrouded in hagiographic lore. In such systems, the leader is not merely a politician but an embodiment of the nation’s soul, a living symbol of its sacred narrative. This deification serves a dual purpose: it personalizes the abstract ideals of the regime, making them more relatable, while also ensuring that loyalty to the state is inseparable from loyalty to the leader. The cult of personality thrives on spectacle—parades, monuments, and rituals—that reinforce the leader’s omnipotence and the citizen’s subservience.

Absolute loyalty is the final pillar, the non-negotiable demand that defines membership in the political religion. In these systems, loyalty is not a choice but a duty, enforced through fear, indoctrination, and social pressure. The Khmer Rouge’s Year Zero policy, which sought to erase all traces of Cambodia’s past, exemplifies this extreme demand for allegiance. Citizens were compelled to renounce family, property, and even their own memories in service to the regime’s vision. Betrayal is not merely a crime but a heresy, punishable by ostracism, imprisonment, or death. This unwavering loyalty is sustained through a culture of surveillance, where neighbors, friends, and even family members are encouraged to report deviations from the orthodoxy. The result is a society where trust is eroded, and conformity is the only safe option.

In practice, these characteristics intertwine to create a suffocating ecosystem of control and belief. Totalitarianism provides the structure, sacred narratives the purpose, the cult of personality the focus, and absolute loyalty the glue. Together, they transform politics into a religion, demanding not just obedience but worship. For those living under such regimes, the line between state and soul blurs, leaving little room for resistance or hope. Understanding these mechanisms is not just an academic exercise but a cautionary tale, a reminder of the fragility of freedom in the face of ideologies that seek to dominate every aspect of human existence.

Political Machines: Unveiling Their Surprising Benefits and Historical Impact

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: Fascism, Communism, and extreme nationalism as political religion manifestations

The concept of political religion finds its most chilling manifestations in the 20th century's ideological behemoths: Fascism, Communism, and extreme nationalism. These movements, though differing in their stated goals, shared a common blueprint: they demanded absolute loyalty, fostered cults of personality, and promised utopian futures achievable only through sacrifice and struggle.

Fascism, exemplified by Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany, erected a secular altar to the nation-state. The Führer and Il Duce became quasi-divine figures, their words scripture, their images omnipresent. Mass rallies, choreographed spectacles, and a relentless propaganda machine replaced traditional religious rituals, channeling devotion towards the state and its leader. Dissent was heresy, punished with brutal efficiency.

Communism, as practiced in the Soviet Union and Mao's China, offered a different flavor of political religion. Here, the deity was history itself, marching inexorably towards a worker's paradise. Marx and Lenin were the prophets, their writings sacred texts. The Party became the priesthood, interpreting doctrine and enforcing orthodoxy. Millions perished in the name of this secular faith, sacrificed on the altar of progress. The gulags and Cultural Revolution were its inquisitions, purging heretics and enforcing ideological purity.

Extreme nationalism, often intertwined with both Fascism and Communism, deified the nation itself. Blood and soil became sacred, ethnic identity a religious creed. Enemies, both internal and external, were demonized as existential threats to the nation's purity. This toxic brew fueled genocides like the Holocaust and the Rwandan massacre, where entire populations were sacrificed to the idol of national superiority.

These historical examples demonstrate the dangers of politicized faith. When ideology replaces reason, when leaders become messiahs, and when dissent is silenced, the result is invariably catastrophe. Recognizing the hallmarks of political religion – the cult of personality, the demand for absolute loyalty, the promise of utopia through sacrifice – is crucial for safeguarding democratic values and preventing history from repeating itself.

Is Liberalism a Political Ideology? Exploring Its Core Principles and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Propaganda: Manipulates beliefs, shapes identity, and enforces conformity through media and education

Propaganda is the lifeblood of political religions, serving as the primary tool to mold minds and maintain control. Unlike traditional persuasion, which appeals to reason and evidence, propaganda operates on emotion, repetition, and exclusionary narratives. It doesn’t merely inform—it infects, embedding itself into the subconscious through relentless exposure. In political religions, propaganda functions as a secular scripture, replacing critical thought with blind devotion. Its power lies in its ability to make the absurd seem normal, the oppressive seem protective, and dissent seem treasonous.

Consider the mechanics of propaganda in action: it begins by simplifying complex issues into binary choices—us versus them, good versus evil. This reductionism strips away nuance, making it easier to manipulate beliefs. For instance, Nazi Germany’s use of posters, films, and public speeches portrayed Jews as subhuman threats, while simultaneously glorifying Aryan superiority. The constant barrage of such messages, amplified through state-controlled media and education, reshaped national identity around hatred and exclusion. Similarly, in modern contexts, social media algorithms act as unwitting propagandists, reinforcing echo chambers that harden beliefs and demonize opposition.

Education systems in political religions are not neutral transmitters of knowledge but instruments of indoctrination. Textbooks are rewritten to glorify the regime, erase historical inaccuracies, and vilify enemies. Children are taught not just facts but a worldview—one that positions the political ideology as the ultimate truth. For example, Mao Zedong’s *Little Red Book* was distributed to millions of Chinese students, its slogans memorized and recited daily, embedding loyalty to the Communist Party into the very fabric of their identity. This isn’t education; it’s identity engineering, where conformity is rewarded and deviation is punished.

Media, too, plays a dual role: as both amplifier and enforcer. State-controlled outlets broadcast narratives that reinforce the political religion’s core tenets, while dissent is silenced or discredited. In North Korea, the cult of personality surrounding the Kim dynasty is perpetuated through omnipresent propaganda—portraits, statues, and daily broadcasts that deify the leaders. Citizens are not just informed; they are immersed in a reality where questioning the regime is unthinkable. Even in democracies, media can be co-opted to shape public opinion, as seen in the use of fear-mongering during election cycles or the weaponization of misinformation to discredit opponents.

The ultimate goal of propaganda in political religions is conformity—not just outward compliance but inward alignment. It seeks to eliminate the space between private thought and public action, making dissent psychologically impossible. This is achieved through constant surveillance, both literal and perceived. In Orwell’s *1984*, the omnipresent Big Brother symbolizes this dynamic: citizens police their own thoughts, fearing even the slightest deviation from the Party line. In real-world political religions, this manifests as self-censorship, where individuals internalize the ideology to such a degree that they become their own enforcers.

To resist propaganda’s grip, one must cultivate media literacy and critical thinking. Question the source, analyze the intent, and seek diverse perspectives. Educate yourself and others on the tactics of manipulation—repetition, emotional appeals, and false dichotomies. In an age of information overload, the ability to discern truth from propaganda is not just a skill; it’s a survival mechanism. Political religions thrive on conformity, but their power wanes when individuals refuse to be molded. The antidote to propaganda is not silence but informed, unwavering dissent.

Understanding Political Unemployment: Causes, Impact, and Economic Consequences

You may want to see also

Criticism and Debate: Challenges its validity as a concept and its applicability to modern politics

The concept of political religion, while intriguing, faces significant criticism for its ambiguity and potential misuse. Critics argue that the term lacks a precise definition, blending religious and political elements in ways that can obscure rather than clarify analysis. For instance, scholars like Emilio Gentile emphasize the need for clear criteria to distinguish political religions from secular ideologies or traditional religions. Without such boundaries, the concept risks becoming a catch-all label, diluting its analytical power. This vagueness raises questions about its utility in understanding modern political movements, where the lines between ideology, nationalism, and religious fervor are increasingly blurred.

One major challenge to the concept’s validity lies in its historical application. Critics point out that labeling regimes like Nazi Germany or Soviet communism as political religions can oversimplify their complex origins and structures. For example, while both regimes exhibited cult-like devotion to leaders and utopian visions, they differed fundamentally in their ideological foundations and methods of control. Applying the term uniformly risks ignoring these nuances, potentially leading to flawed comparisons. This critique underscores the danger of treating political religion as a one-size-fits-all framework rather than a tool for nuanced analysis.

Another contentious issue is the concept’s applicability to contemporary politics. Some argue that modern movements, such as populism or environmentalism, do not fit neatly into the political religion mold. While these movements may inspire fervent loyalty and moral absolutism, they lack the centralized authority and ritualistic structures often associated with political religions. For instance, climate activism, though driven by a sense of urgency and shared purpose, operates through decentralized networks rather than a hierarchical, cult-like organization. This mismatch highlights the limitations of applying a historically rooted concept to fluid, evolving political phenomena.

Despite these challenges, defenders of the concept argue that it remains a valuable lens for identifying dangerous trends in politics. They contend that political religion highlights the risks of ideologies that demand absolute adherence, suppress dissent, and dehumanize opponents—traits observable in both historical and contemporary contexts. However, to retain its relevance, the concept must evolve. Scholars suggest refining its definition to focus on specific criteria, such as the sacralization of political goals, the cult of personality, and the use of ritual to mobilize masses. Such precision could enhance its applicability while addressing current criticisms.

In practical terms, understanding the debates around political religion requires a critical approach. Analysts should avoid reflexively applying the label and instead scrutinize movements for specific indicators of religious-like behavior. For example, examining how a movement frames its mission, treats its leaders, and responds to dissent can provide clearer insights than relying on broad categorizations. By adopting this method, the concept can serve as a warning system for authoritarian tendencies rather than a reductive label. Ultimately, the value of political religion lies not in its universality but in its ability to illuminate specific dangers within political systems.

Understanding Political Ramifications: Impacts, Consequences, and Societal Shifts Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political religion is an ideological system that functions like a religion but is centered around political goals, symbols, or leaders, often demanding absolute loyalty and devotion.

While traditional religions focus on spiritual or supernatural beliefs, political religions replace these with secular ideologies, such as nationalism or communism, and often use state power to enforce their doctrines.

Examples include Stalinism in the Soviet Union, Nazism in Germany, and the Cult of the Supreme Leader in North Korea, where political ideologies were treated as sacred and dissent was suppressed.

While less common, elements of political religion can emerge in democracies when extreme nationalism, populism, or ideological purity tests dominate public discourse and undermine pluralism.

Political religions often lead to totalitarianism, the suppression of individual freedoms, and the dehumanization of opponents, as they prioritize the collective ideology over human rights and diversity.