A political party, as defined in AP Government, is a group of individuals who share common political beliefs, interests, and goals, and who organize to win elections, control government power, and influence public policy. In the United States, the two dominant political parties are the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, though smaller parties like the Libertarian and Green Parties also play roles in the political landscape. Political parties serve multiple functions, including recruiting and nominating candidates, mobilizing voters, and shaping public opinion through platforms and campaigns. Understanding the structure, roles, and impact of political parties is essential for grasping the dynamics of American governance and the electoral process, as they are central to how power is distributed and exercised in the political system.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A group organized to win elections, operate government, and determine public policy. |

| Primary Function | To gain political power and influence government decisions. |

| Key Roles | Nominating candidates, mobilizing voters, and shaping public opinion. |

| Structure | Hierarchical, with local, state, and national committees. |

| Funding Sources | Donations from individuals, corporations, PACs, and party fundraising. |

| Ideology | Represents specific political beliefs and policy positions. |

| Voter Base | Appeals to specific demographics, regions, or interest groups. |

| Examples (U.S.) | Democratic Party, Republican Party, Libertarian Party, Green Party. |

| Party Platforms | Formal statements of a party's policies and goals. |

| Role in Elections | Provides resources, endorsements, and campaign support to candidates. |

| Legislative Influence | Shapes laws and policies through party caucuses and leadership. |

| Party Identification | Individuals align with a party based on beliefs, values, or tradition. |

| Two-Party System (U.S.) | Dominance of Democrats and Republicans in U.S. politics. |

| Third Parties | Smaller parties with limited electoral success but significant influence. |

| Party Realignment | Shifts in party coalitions and voter bases over time. |

Explore related products

$9.99 $14.99

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Role: Political parties organize citizens with shared ideologies to influence government policies and leadership

- Functions: Recruit candidates, mobilize voters, fundraise, and shape public opinion through campaigns

- Two-Party System: Dominance of Democrats and Republicans in U.S. politics, limiting third-party success

- Party Organization: Local, state, and national committees coordinate activities and platform development

- Party Realignment: Shifts in voter coalitions and issue priorities, altering party dominance over time

Definition and Role: Political parties organize citizens with shared ideologies to influence government policies and leadership

Political parties serve as the backbone of democratic systems, acting as intermediaries between citizens and government. At their core, they are coalitions of individuals united by common beliefs, values, and policy goals. This shared ideology is the glue that binds party members together, enabling them to collectively advocate for specific changes in governance. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States emphasizes social equality and government intervention, while the Republican Party prioritizes individual liberty and limited government. These ideological frameworks guide party platforms, shaping their stances on issues like healthcare, taxation, and foreign policy.

To effectively influence government policies and leadership, political parties employ a multi-step strategy. First, they mobilize voters through grassroots campaigns, rallies, and media outreach. This mobilization is critical during elections, where parties aim to secure seats in legislative bodies and executive offices. Second, they develop and promote policy agendas that reflect their ideological commitments. For example, a party advocating for environmental sustainability might push for stricter emissions regulations or renewable energy subsidies. Third, parties negotiate and form coalitions within government to advance their agendas, often requiring compromise to achieve legislative victories.

One of the most practical ways political parties influence leadership is through candidate recruitment and endorsement. Parties identify individuals who align with their ideologies and support them financially, logistically, and publicly. This process ensures that elected officials are likely to champion the party’s priorities once in office. For instance, during primary elections, parties often back candidates who best represent their core values, even if it means challenging incumbents. This strategic approach helps maintain ideological consistency within the party ranks.

However, the role of political parties is not without challenges. Internal factions can arise when members disagree on specific policies or strategies, leading to divisions that weaken the party’s influence. Additionally, parties must balance their ideological purity with the need to appeal to a broader electorate, a delicate task that often requires nuanced messaging. For example, a party might soften its stance on a controversial issue to attract moderate voters, risking backlash from its base. Navigating these tensions is essential for maintaining both party unity and electoral viability.

In conclusion, political parties are dynamic organizations that translate shared ideologies into actionable political influence. By organizing citizens, shaping policy agendas, and cultivating leadership, they play a pivotal role in democratic governance. Understanding their definition and function is crucial for anyone studying AP Government, as it highlights the mechanisms through which public opinion is transformed into government action. Whether through voter mobilization, policy advocacy, or candidate selection, parties are indispensable tools for those seeking to impact the political landscape.

Understanding the Political Compass: A Guide to Ideological Navigation

You may want to see also

Functions: Recruit candidates, mobilize voters, fundraise, and shape public opinion through campaigns

Political parties are the backbone of democratic systems, serving as essential mechanisms for organizing political life. One of their primary functions is to recruit candidates who can effectively represent the party’s platform and values. This process involves identifying individuals with the right mix of charisma, policy knowledge, and electability. For instance, the Democratic Party in the U.S. often seeks candidates who align with progressive ideals, while the Republican Party looks for those who champion conservative principles. This recruitment is not random; it is a strategic effort to ensure the party’s message resonates with voters and that its candidates can compete effectively in elections.

Once candidates are in place, the next critical function is to mobilize voters. This involves a multi-faceted approach, including grassroots organizing, door-to-door canvassing, and digital outreach. Parties use data analytics to target specific demographics, such as young voters or minority groups, tailoring messages to address their concerns. For example, during the 2020 U.S. presidential election, both major parties employed sophisticated voter turnout strategies, including text messaging campaigns and social media ads, to encourage participation. Effective mobilization can swing elections, making it a cornerstone of party operations.

Fundraising is another vital function, as campaigns require significant financial resources to operate. Parties raise funds through donations from individuals, corporations, and political action committees (PACs). The 2020 election cycle saw record-breaking fundraising, with candidates like Joe Biden and Donald Trump raising over $1 billion each. However, fundraising is not without challenges. Parties must navigate campaign finance laws, such as contribution limits, and balance the need for resources with the risk of appearing beholden to wealthy donors. Transparency and ethical practices are crucial to maintaining public trust.

Finally, parties shape public opinion through campaigns, using messaging, advertising, and media appearances to influence voter perceptions. This function is both art and science, requiring a deep understanding of public sentiment and effective communication strategies. For instance, the 2008 Obama campaign revolutionized political messaging by emphasizing hope and change, resonating with a broad spectrum of voters. Conversely, negative campaigning, such as attack ads, can also sway opinions, though it risks alienating undecided voters. The goal is to frame issues in a way that aligns with the party’s agenda while countering opponents’ narratives.

In practice, these functions are interdependent. Recruiting strong candidates makes fundraising easier, as donors are more likely to support viable contenders. Mobilizing voters amplifies the impact of campaign messaging, ensuring that the party’s narrative reaches a wide audience. Together, these activities form the core of a party’s operational strategy, enabling it to compete effectively in elections and advance its policy goals. Without these functions, political parties would struggle to maintain relevance in a crowded and competitive political landscape.

Unveiling the Power Players: Understanding the Role of Political Bosses

You may want to see also

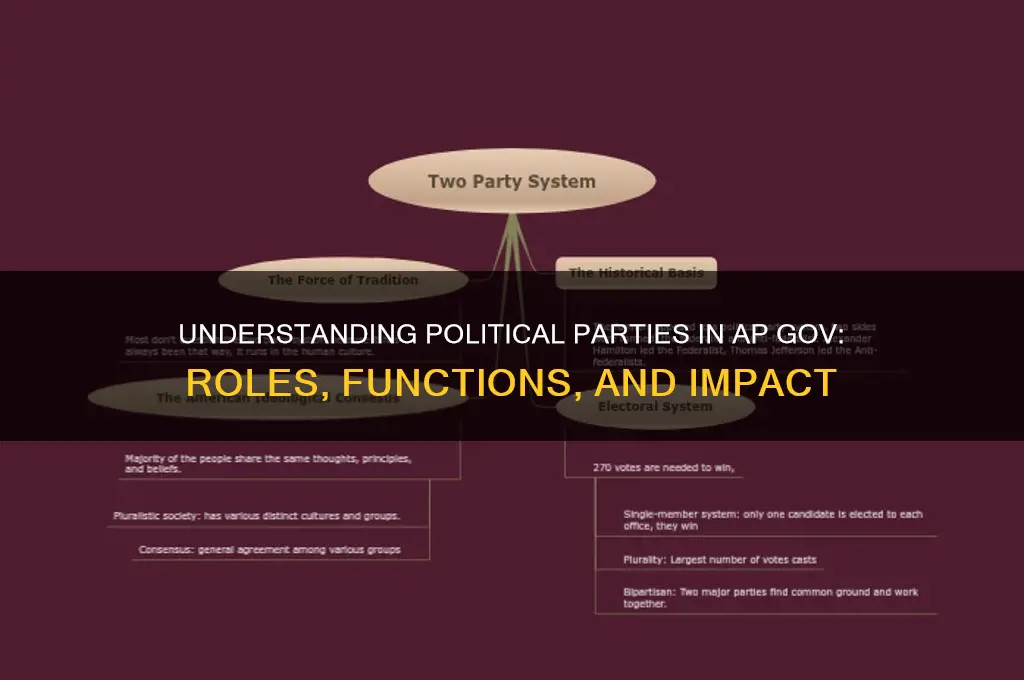

Two-Party System: Dominance of Democrats and Republicans in U.S. politics, limiting third-party success

The United States operates under a two-party system, where the Democratic and Republican parties dominate the political landscape. This duopoly is not enshrined in law but is a product of historical, institutional, and cultural factors. The winner-take-all electoral system, where the candidate with the most votes in a state wins all its electoral votes, incentivizes voters to support one of the two major parties to avoid "wasting" their vote. This structural advantage creates a feedback loop: more funding, media attention, and ballot access flow to Democrats and Republicans, further solidifying their dominance.

Consider the challenges faced by third parties like the Libertarians or Greens. Despite occasional surges in popularity, they rarely secure federal office. Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential campaign, which garnered 18.9% of the popular vote, is often cited as a high-water mark for third-party success. Yet, it failed to translate into electoral votes or lasting influence. This illustrates the system’s resistance to change: even a well-funded, charismatic candidate struggles to overcome the structural barriers favoring the two major parties.

To understand why third parties falter, examine the role of primaries and campaign financing. The Democratic and Republican parties control the primary process, which acts as a gatekeeper for political legitimacy. Candidates outside this framework must navigate stricter ballot access requirements and lack access to public funding, which is reserved for major-party nominees. For instance, a third-party candidate must collect thousands of signatures in each state just to appear on the ballot, a logistical and financial hurdle that major-party candidates bypass.

Despite these obstacles, third parties play a crucial role in shaping political discourse. The Progressive Party of the early 20th century pushed for labor rights and women’s suffrage, ideas later adopted by the Democrats. Similarly, the Libertarian Party’s emphasis on limited government has influenced Republican policy on issues like criminal justice reform. While third parties may not win elections, they act as catalysts for change, forcing the major parties to address issues they might otherwise ignore.

Breaking the two-party system would require fundamental reforms. Ranked-choice voting, already implemented in some local elections, could reduce the "spoiler effect" by allowing voters to rank candidates in order of preference. Proportional representation, used in many parliamentary systems, would allocate seats based on parties’ share of the vote, giving smaller parties a voice. However, such changes face resistance from the very parties that benefit from the current system. Until then, the Democrats and Republicans will continue to dominate, leaving third parties on the periphery of American politics.

Discover Your Political Identity: Take the Party Affiliation Quiz Now

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Party Organization: Local, state, and national committees coordinate activities and platform development

Political parties are not monolithic entities but complex networks of committees operating at local, state, and national levels. Each tier plays a distinct role in coordinating activities and shaping the party’s platform, ensuring alignment from grassroots efforts to federal strategies. Understanding this hierarchical structure is essential for grasping how parties function in American governance.

At the local level, committees serve as the boots on the ground, mobilizing voters, organizing events, and recruiting candidates for municipal or county offices. These committees are often volunteer-driven and focus on immediate community concerns, such as school board elections or zoning issues. For instance, a local Democratic committee might host voter registration drives or canvass neighborhoods to promote a candidate. Their work is hyper-specific, tailored to the needs and demographics of their area, making them the foundation of a party’s strength.

Moving up to the state level, committees take on broader responsibilities, including fundraising, coordinating campaigns for state legislatures and governorships, and ensuring consistency with the national party’s platform. They act as intermediaries, balancing local priorities with statewide strategies. For example, a state Republican committee might develop a unified message on tax policy that resonates across diverse districts. These committees also play a critical role in redistricting efforts, which can significantly impact electoral outcomes.

The national committees—such as the Democratic National Committee (DNC) or Republican National Committee (RNC)—oversee the party’s overall direction, manage presidential campaigns, and set the national platform. They are responsible for high-stakes tasks like organizing national conventions, coordinating media strategies, and raising millions of dollars for federal races. Unlike local and state committees, national committees operate with a more centralized structure, often staffed by professionals and guided by party leaders. Their decisions influence not just elections but also the party’s ideological identity.

Coordination across these levels is both a strength and a challenge. While local committees provide grassroots energy, national committees offer resources and strategic direction. However, misalignment can lead to internal conflicts, as seen in debates over issues like healthcare or climate policy. Effective party organization requires clear communication and shared goals, ensuring that local efforts amplify national priorities without losing sight of regional nuances.

In practice, this tiered system allows parties to adapt to diverse political landscapes. For instance, a rural local committee might focus on agricultural policies, while an urban one prioritizes public transportation. State committees synthesize these concerns, and national committees integrate them into a cohesive platform. This dynamic structure ensures that parties remain relevant across the country, from small towns to major cities, and from state capitals to Washington, D.C.

By examining these committees, it becomes clear that party organization is not just about winning elections but about building a sustainable framework for political influence. Each level contributes uniquely, creating a system that is both flexible and powerful—a key to understanding political parties in AP Gov and beyond.

Is New Jersey Still Recognizing Independent Political Parties in 2023?

You may want to see also

Party Realignment: Shifts in voter coalitions and issue priorities, altering party dominance over time

Political parties are not static entities; they evolve in response to shifting voter coalitions and changing issue priorities. Party realignment occurs when these shifts are significant enough to alter the balance of power between parties, often leading to a new era of political dominance. For instance, the post-Civil War era saw the Republican Party, initially a coalition of abolitionists and industrialists, solidify its hold on the North, while the Democratic Party became the dominant force in the South, a pattern that persisted for nearly a century. This realignment was driven by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights, illustrating how foundational issues can reshape party identities.

To understand party realignment, consider it as a three-step process: identification of emerging issues, reconfiguration of voter coalitions, and consolidation of new party dominance. Emerging issues—such as civil rights in the 1960s or economic inequality in the 2010s—create fault lines within existing coalitions. For example, the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights legislation in the 1960s alienated many Southern conservatives, who gradually shifted their allegiance to the Republican Party. This reconfiguration of voter coalitions is not instantaneous; it often takes decades, as seen in the "Solid South" transitioning from Democratic to Republican stronghold.

A cautionary note: party realignment is not merely about parties switching positions on issues. It involves a fundamental restructuring of the electorate’s priorities and allegiances. For instance, the modern Republican Party’s focus on cultural conservatism and limited government grew out of its ability to attract disaffected Democrats and independent voters in the late 20th century. Similarly, the Democratic Party’s current coalition of urban professionals, minorities, and young voters reflects its adaptation to issues like climate change, healthcare, and social justice. Parties that fail to adapt risk obsolescence, as seen with the Whig Party in the 1850s.

Practical tips for analyzing realignment: track demographic shifts (e.g., urbanization, immigration), monitor issue salience in polls, and observe cross-party voting patterns. For example, the 2008 and 2012 elections demonstrated how the growing influence of Latino voters strengthened the Democratic Party’s coalition, while the 2016 election highlighted the appeal of economic populism to white working-class voters, benefiting the Republican Party. By examining these trends, one can predict potential realignments, such as the increasing importance of suburban voters or the role of generational divides in shaping future party dominance.

In conclusion, party realignment is a dynamic process driven by the interplay of voter coalitions and issue priorities. It is not a linear progression but a complex adaptation to societal changes. Understanding this process requires a historical perspective, an eye for emerging trends, and a willingness to challenge conventional wisdom. As the political landscape continues to evolve, the ability to recognize and respond to realignment will be crucial for parties seeking to maintain or achieve dominance in the American political system.

Unveiling Corruption: The Whistleblowers Who Exposed Political Machines

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political party is an organized group of people with shared political beliefs and goals that seeks to influence government by electing candidates to public office.

The primary functions include recruiting and nominating candidates, educating and mobilizing voters, and organizing government by forming majorities in legislative bodies.

Political parties aim to win elections and control government, while interest groups focus on influencing policy without directly seeking office.

The two major political parties are the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, which dominate the U.S. political system.

Third parties often introduce new ideas, challenge the status quo, and can influence major party platforms, but they rarely win national elections due to the two-party system.