A political party and an interest group are two distinct yet interconnected entities within the political landscape. A political party is an organized group that seeks to attain and exercise political power by contesting elections and forming governments, typically advocating for a specific ideology, policy agenda, or set of principles. Parties play a central role in democratic systems by mobilizing voters, aggregating interests, and providing a structured framework for governance. In contrast, an interest group, also known as an advocacy group or pressure group, is an organization that aims to influence public policy and decision-making without seeking direct political office. Interest groups represent the specific concerns of their members, such as businesses, labor unions, or social causes, and use various tactics like lobbying, public campaigns, and litigation to shape legislation and public opinion. While political parties focus on winning elections and governing, interest groups concentrate on advancing particular issues or agendas, often collaborating with or opposing parties to achieve their goals. Together, they form a dynamic ecosystem that shapes political discourse and policy outcomes in modern societies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Purpose: Distinguishes political parties from interest groups based on goals and functions

- Structure and Organization: Explores hierarchical vs. decentralized models in parties and interest groups

- Role in Democracy: Analyzes how both entities influence policy and representation in governance

- Funding and Resources: Compares financial sources and resource allocation strategies for each group

- Strategies and Tactics: Highlights lobbying, campaigning, and mobilization methods used by parties and groups

Definition and Purpose: Distinguishes political parties from interest groups based on goals and functions

Political parties and interest groups are often conflated, yet their goals and functions diverge sharply. At their core, political parties are organizations that seek to gain and wield governmental power by winning elections and controlling policy-making institutions. Their primary objective is to secure a majority or plurality of seats in legislative bodies, enabling them to shape and implement broad-ranging policies that reflect their ideological platforms. For instance, the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States compete to control Congress and the presidency, each advocating distinct visions for governance. In contrast, interest groups operate outside the electoral arena, focusing on influencing policy outcomes without directly seeking political office. Their purpose is to advance specific causes or represent particular constituencies, such as labor unions, environmental organizations, or business associations. While political parties aim to govern, interest groups aim to lobby.

Consider the mechanics of their operations to further distinguish these entities. Political parties are structured to mobilize voters, recruit candidates, and coordinate campaigns across multiple levels of government. They rely on mass membership and broad appeals to secure electoral victories. Interest groups, however, employ targeted strategies like lobbying, litigation, and grassroots advocacy to sway policymakers. For example, the National Rifle Association (NRA) does not run candidates for office but instead pressures legislators to oppose gun control measures. This functional difference underscores their distinct roles: parties aggregate diverse interests into cohesive platforms, while interest groups amplify specific concerns within the political system.

A persuasive argument can be made that these differences reflect complementary, yet inherently separate, roles in democratic systems. Political parties serve as the backbone of representative governance, providing voters with clear choices and ensuring accountability through elections. Interest groups, meanwhile, act as checks on party dominance, ensuring that niche or minority perspectives are not overlooked. However, this dynamic is not without tension. Parties must balance the demands of their ideological base with the need for broad appeal, while interest groups risk being perceived as narrow or self-serving. For instance, a party might moderate its stance on climate change to attract centrist voters, even as environmental interest groups push for more radical action.

To illustrate these distinctions practically, imagine a policy debate on healthcare reform. A political party might propose a comprehensive bill that balances cost, coverage, and political feasibility, aiming to appeal to a wide electorate. An interest group, such as AARP, would focus narrowly on how the bill affects seniors, potentially advocating for specific provisions like prescription drug subsidies. This example highlights the parties’ role in synthesizing diverse interests into actionable policy, versus interest groups’ role in spotlighting particular concerns. Both are essential, but their functions are non-interchangeable.

In conclusion, while political parties and interest groups are integral to democratic politics, their goals and functions are fundamentally different. Parties seek power to govern and implement broad policies, whereas interest groups aim to influence those policies without governing directly. Understanding this distinction is crucial for navigating the complexities of political systems and appreciating the unique contributions of each entity. Whether through electoral competition or targeted advocacy, both play indispensable roles in shaping public policy and representing societal interests.

When It Comes to Politics: Navigating the Complex World of Power and Policy

You may want to see also

Structure and Organization: Explores hierarchical vs. decentralized models in parties and interest groups

Political parties and interest groups often mirror corporate structures, but their organizational models can sharply diverge. Hierarchical models, common in established political parties, feature a clear chain of command: leaders at the top make decisions, and lower tiers execute them. This structure ensures unity and efficiency, as seen in the Democratic and Republican parties in the U.S., where national committees dictate strategy and messaging. In contrast, decentralized models, often found in grassroots interest groups like Black Lives Matter or Extinction Rebellion, distribute power across local chapters or members. This approach fosters flexibility and inclusivity but can lead to fragmented efforts and slower decision-making.

Consider the practical implications of these models. A hierarchical party can swiftly mobilize resources for a national campaign, ensuring consistent branding and messaging. For instance, during election seasons, the Republican National Committee coordinates fundraising, advertising, and voter outreach with precision. However, this centralization can stifle local innovation and alienate members who feel disconnected from leadership. Decentralized interest groups, on the other hand, thrive on local autonomy. The Sierra Club, for example, allows regional chapters to tailor campaigns to local environmental issues, but this can result in inconsistent national impact.

To choose between models, assess your organization’s goals. If unity and rapid response are critical, adopt a hierarchical structure. Assign clear roles—chairperson, treasurer, communications director—and establish regular reporting lines. For interest groups prioritizing member engagement and adaptability, decentralize by creating independent committees or chapters with decision-making power. Tools like Slack or Trello can facilitate coordination without sacrificing autonomy. Caution: hybrid models, while appealing, often blur accountability. Define boundaries clearly to avoid confusion.

A persuasive argument for decentralization lies in its resilience. Hierarchical structures crumble when leadership falters, as seen in parties embroiled in scandals. Decentralized groups, however, can survive leadership changes because power isn’t concentrated. Occupy Wall Street, despite lacking formal leaders, sustained global influence through its network-based organization. Yet, decentralization isn’t foolproof. Without shared goals, efforts disperse, as evidenced by some anti-war coalitions in the 2000s. Balance is key: retain a core mission while allowing flexibility.

Finally, analyze historical examples for lessons. The Tea Party movement succeeded by blending decentralized local activism with hierarchical national coordination, amplifying its impact. Conversely, the Green Party’s struggle for cohesion highlights the risks of over-decentralization. For new organizations, start with a decentralized model to foster engagement, then introduce hierarchical elements as needed. Regularly evaluate structure against outcomes—what works for a 10-person group may fail for a 10,000-member organization. Adaptability, not rigidity, ensures longevity.

Are Populists a Political Party? Exploring the Movement's Identity

You may want to see also

Role in Democracy: Analyzes how both entities influence policy and representation in governance

Political parties and interest groups are the backbone of democratic systems, each playing distinct yet interconnected roles in shaping policy and representation. Parties aggregate diverse interests into coherent platforms, offering voters clear choices during elections. Interest groups, on the other hand, advocate for specific causes, often operating outside electoral politics. Together, they ensure that governance reflects the multifaceted demands of society. However, their influence is not without tension; parties seek broad appeal, while interest groups push for narrow agendas. This dynamic interplay is essential for a functioning democracy, but it also raises questions about whose voices dominate and how power is balanced.

Consider the legislative process, where the role of these entities becomes particularly evident. Political parties control the agenda in most democratic systems, determining which bills are prioritized and how resources are allocated. Interest groups, meanwhile, lobby lawmakers, provide expertise, and mobilize public support to sway decisions. For instance, environmental interest groups may push for stricter regulations, while business-aligned parties advocate for deregulation. This push-and-pull ensures that policies are scrutinized from multiple angles, though it can also lead to gridlock or favoritism. The challenge lies in ensuring that both parties and interest groups serve as conduits for public will rather than tools for special interests.

To understand their impact, examine the 2020 U.S. elections, where political parties framed the debate around healthcare, climate change, and economic recovery. Simultaneously, interest groups like the Sierra Club and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce spent millions on campaigns and lobbying efforts. While parties provided voters with broad visions, interest groups amplified specific issues, such as renewable energy subsidies or tax cuts. This dual mechanism ensures that democracy is not just about majority rule but also about protecting minority rights and specialized concerns. However, it requires vigilance to prevent undue influence, such as corporate funding skewing party priorities or single-issue groups overshadowing broader public interests.

A practical takeaway for citizens is to engage critically with both parties and interest groups. Voters should scrutinize party platforms for consistency and inclusivity while also supporting interest groups that align with their values. For instance, joining a local environmental group or participating in party primaries can amplify individual influence. Policymakers, meanwhile, must balance party loyalty with responsiveness to diverse interest groups, ensuring that governance remains transparent and accountable. Ultimately, the health of a democracy depends on how effectively these entities channel public aspirations into actionable policies.

In conclusion, political parties and interest groups are not mere fixtures of democracy but active agents shaping its trajectory. Their roles are complementary yet distinct, with parties providing structure and interest groups injecting specificity. By understanding their functions and limitations, citizens and leaders alike can harness their potential to foster a more representative and responsive governance system. The key lies in maintaining a delicate equilibrium, where neither entity overshadows the other, and both remain accountable to the people they serve.

Navigating Political Identity: Where Do I Stand in Today’s Landscape?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Funding and Resources: Compares financial sources and resource allocation strategies for each group

Political parties and interest groups are both pivotal in shaping public policy, yet their financial lifelines differ dramatically. Parties primarily rely on a mix of public funding, private donations, and membership dues. In the U.S., for instance, the Federal Election Commission (FEC) allows individuals to contribute up to $3,300 per candidate per election, with party committees capped at $41,300 annually. Interest groups, however, often tap into corporate sponsorships, foundation grants, and grassroots fundraising. The National Rifle Association (NRA), for example, generates revenue through membership fees, merchandise sales, and donations from gun manufacturers, showcasing a diversified funding model.

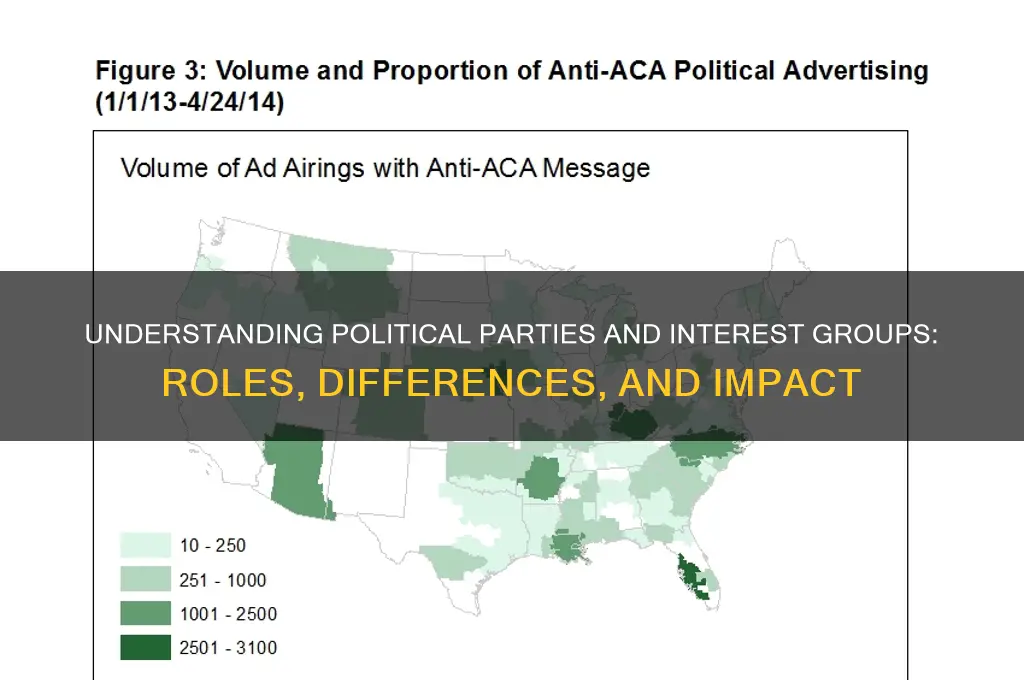

Resource allocation strategies further highlight the distinct priorities of these entities. Political parties focus on campaign infrastructure, such as hiring staff, running ads, and organizing rallies. During the 2020 U.S. presidential election, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) allocated over $100 million to digital advertising alone. Interest groups, in contrast, prioritize lobbying efforts, research, and public awareness campaigns. The Sierra Club, an environmental advocacy group, spends millions annually on policy research and grassroots mobilization, often targeting specific legislative battles like climate change bills.

A persuasive argument emerges when examining the transparency of these financial flows. Political parties are subject to stricter disclosure requirements under laws like the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which mandates reporting contributions over $200. Interest groups, particularly those registered as 501(c)(4) organizations, enjoy more opacity, allowing them to shield donor identities. This disparity raises questions about accountability and the potential for undue influence in the political process.

To navigate these financial landscapes effectively, consider these practical tips. For political parties, leveraging small-dollar donations through platforms like ActBlue can broaden support while staying within legal limits. Interest groups, meanwhile, should focus on building sustainable revenue streams, such as recurring membership programs or partnerships with aligned businesses. Both groups must prioritize transparency to maintain public trust, even if legal requirements are minimal.

In conclusion, while political parties and interest groups share the goal of influencing policy, their funding sources and resource allocation strategies reflect distinct operational realities. Parties lean on regulated donations and public funds to fuel campaigns, while interest groups thrive on diverse, often less transparent, revenue streams. Understanding these differences is crucial for anyone seeking to engage with or regulate these powerful actors in the political arena.

Understanding SNP's Role and Impact in British Politics Explained

You may want to see also

Strategies and Tactics: Highlights lobbying, campaigning, and mobilization methods used by parties and groups

Political parties and interest groups are the architects of influence, employing a toolkit of strategies and tactics to shape policies and public opinion. At the heart of their efforts lie lobbying, campaigning, and mobilization—each a distinct yet interconnected method to achieve their goals. Lobbying, often conducted behind closed doors, involves direct communication with policymakers to advocate for specific legislation or regulatory changes. For instance, the American Medical Association (AMA) lobbies Congress to influence healthcare policies, leveraging its expertise and resources to sway decisions in favor of its members. This method requires precision, timing, and often, substantial financial backing to maintain access to key decision-makers.

Campaigning, on the other hand, is a public-facing strategy designed to win elections or build support for a cause. Political parties invest heavily in data analytics, social media, and grassroots outreach to target voters effectively. Interest groups, like the Sierra Club, use campaigns to raise awareness about environmental issues, often partnering with political parties to align their agendas. A successful campaign hinges on storytelling, emotional appeal, and the ability to cut through the noise of competing messages. For example, the 2008 Obama campaign revolutionized digital campaigning by using platforms like Facebook and Twitter to mobilize young voters, demonstrating the power of technology in modern political strategies.

Mobilization is the engine that drives both lobbying and campaigning, transforming passive supporters into active participants. Interest groups like the National Rifle Association (NRA) excel at mobilizing their base through rallies, petitions, and voter registration drives. Political parties, meanwhile, rely on door-to-door canvassing, phone banking, and volunteer networks to turn out voters on Election Day. Effective mobilization requires a clear call to action, a sense of urgency, and the ability to tap into shared values or grievances. For instance, the Women’s March in 2017 mobilized millions globally by framing the protest as a defense of women’s rights, showcasing how mobilization can amplify a movement’s impact.

While these strategies are powerful, they are not without risks. Over-reliance on lobbying can lead to accusations of elitism or corruption, as seen in cases where corporate interests dominate policy discussions. Campaigning, if mismanaged, can backfire, alienating voters with polarizing messages or misinformation. Mobilization efforts, too, can falter if they fail to resonate with diverse audiences or if they lack sustainable infrastructure. For example, the Occupy Wall Street movement struggled to translate its initial mobilization into concrete policy changes due to a lack of clear leadership and organizational structure.

In practice, the most effective political parties and interest groups blend these strategies seamlessly, adapting them to the context and audience. A labor union might lobby for worker protections while simultaneously running a public campaign to garner public support and mobilizing its members to strike if necessary. The key lies in understanding the strengths and limitations of each tactic and deploying them strategically. For those looking to engage in political advocacy, start by identifying your primary goal: is it to influence policymakers directly, build public support, or activate a specific group? Tailor your approach accordingly, and remember that success often comes from combining these methods in a cohesive, well-timed strategy.

Joining a Political Party: Key Requirements and Membership Criteria Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political party is an organized group of people who share common political goals and seek to influence government policies by electing their members to public office.

An interest group is an organization of individuals or entities that advocates for specific policies or issues, often to influence government decisions without seeking direct political office.

Political parties aim to win elections and control government, while interest groups focus on advocating for specific issues or policies without running candidates for office.

Yes, individuals can belong to both, as political parties and interest groups often align on certain issues, but they serve distinct purposes in the political system.