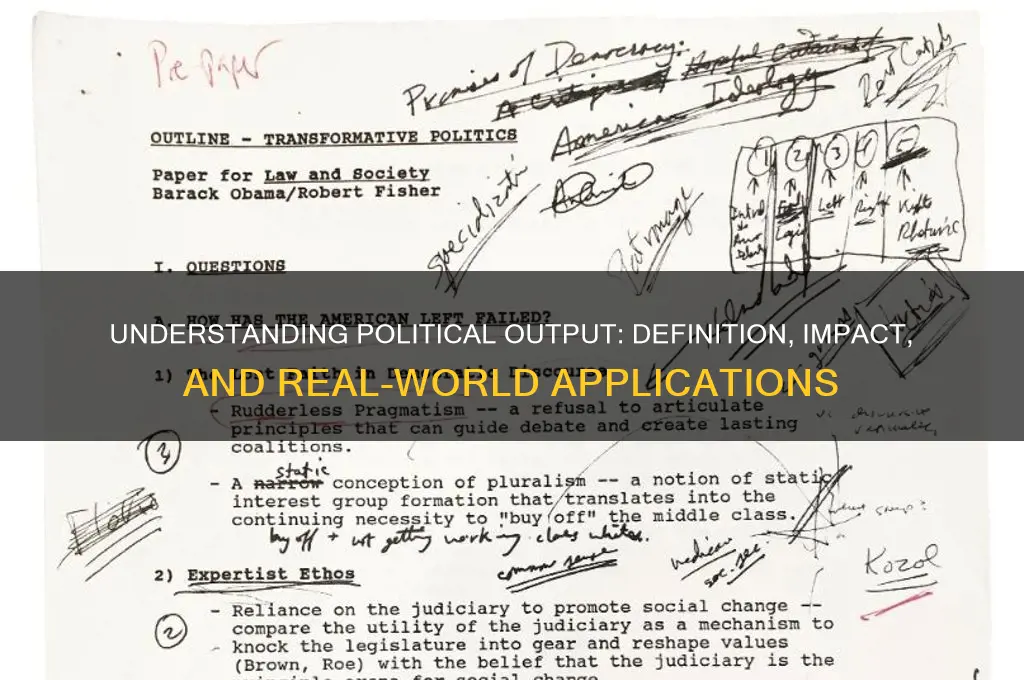

Political output refers to the tangible results, policies, and actions produced by political systems, institutions, or actors in response to societal demands, interests, and challenges. It encompasses a wide range of outcomes, including legislation, regulations, public services, and international agreements, which are shaped by the interplay of government, political parties, interest groups, and citizens. Understanding political output is crucial for assessing the effectiveness of governance, the alignment of policies with public needs, and the broader impact of political decisions on economic, social, and cultural spheres. By analyzing political output, scholars and practitioners can evaluate the responsiveness, accountability, and legitimacy of political systems, shedding light on how power is exercised and resources are allocated in society.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The tangible and intangible results of political processes, institutions, and decisions. |

| Types | Policies, laws, regulations, public services, infrastructure, symbolic actions (e.g., speeches, ceremonies), and international agreements. |

| Purpose | To address societal needs, manage conflicts, allocate resources, and shape public behavior. |

| Actors | Governments, political parties, interest groups, bureaucracies, and international organizations. |

| Measurement | Quantitative (e.g., budget allocations, policy implementation rates) and qualitative (e.g., public satisfaction, policy impact assessments). |

| Examples | Healthcare reforms, tax legislation, climate change agreements, public education programs, and diplomatic treaties. |

| Impact | Shapes societal norms, economic conditions, and quality of life; influences power dynamics and citizen trust in institutions. |

| Challenges | Implementation gaps, political polarization, resource constraints, and unintended consequences. |

| Recent Trends | Increased focus on digital governance, sustainability policies, and global cooperation on issues like pandemics and cybersecurity. |

| Key Metrics | Policy effectiveness, public approval ratings, economic indicators, and compliance with international standards. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Legislation and Policies: Laws, regulations, and policies enacted by governments to govern society

- Public Services: Provision of healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social welfare by the state

- Economic Measures: Fiscal and monetary policies, taxation, and trade agreements shaping economies

- Foreign Relations: Diplomatic actions, treaties, and international alliances influencing global standing

- Social Programs: Initiatives addressing inequality, poverty, and community development for societal well-being

Legislation and Policies: Laws, regulations, and policies enacted by governments to govern society

Governments wield legislation and policies as their primary tools for shaping societal norms, behaviors, and outcomes. These formal rules, crafted through democratic or authoritarian processes, dictate everything from economic transactions to personal freedoms. For instance, the Affordable Care Act in the United States restructured healthcare access, mandating insurance coverage for millions while capping out-of-pocket expenses at $8,700 for individuals in 2023. Such laws are not mere words on paper; they are actionable frameworks that allocate resources, define rights, and impose penalties, often with immediate and long-term consequences for citizens and institutions alike.

Consider the lifecycle of a policy: from conception to enforcement, it undergoes rigorous scrutiny and revision. Take the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which standardized data privacy laws across member states, imposing fines of up to 4% of global revenue for non-compliance. This policy not only protects individual privacy but also reshapes corporate practices globally, as companies operating in the EU must adhere to its stringent requirements. The analytical lens reveals that effective policies balance specificity—clearly defining obligations—with adaptability, allowing for updates in response to technological or societal shifts.

Persuasive arguments often center on the intended versus unintended consequences of legislation. For example, minimum wage laws aim to reduce poverty but can inadvertently lead to reduced hiring or increased automation in labor-intensive industries. A 2021 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that a $15 minimum wage could decrease employment in low-wage sectors by 1.4% while lifting 900,000 out of poverty. Policymakers must weigh these trade-offs, employing data-driven approaches to maximize benefits and mitigate harms. This underscores the importance of evidence-based policy design and iterative evaluation.

Comparatively, the success of legislation often hinges on its implementation and enforcement mechanisms. While Sweden’s parental leave policy—offering 480 days of paid leave per child—achieved high uptake due to strong public trust and administrative efficiency, similar policies in other nations falter due to bureaucratic hurdles or cultural resistance. Practical tips for policymakers include simplifying application processes, ensuring transparency, and engaging stakeholders early in the drafting phase. For citizens, understanding their rights and obligations under new laws—such as tax credits or environmental regulations—can optimize compliance and access to benefits.

Descriptively, policies serve as mirrors reflecting societal values and priorities. The Paris Agreement, ratified by 196 parties, exemplifies global consensus on climate action, with nations committing to limit warming to 1.5°C through nationally determined contributions. Yet, its effectiveness depends on individual countries translating pledges into actionable regulations, such as carbon pricing or renewable energy mandates. This highlights the dual nature of policies: they are both expressions of collective will and instruments of change, requiring collaboration across sectors and borders to achieve their objectives.

China's Political Stability: Assessing Current Environment and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Public Services: Provision of healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social welfare by the state

Public services, encompassing healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social welfare, are the backbone of a functioning society, yet their provision by the state remains a contentious political output. These services are not merely administrative functions but reflect a government’s priorities, values, and commitment to its citizens. For instance, universal healthcare systems, like those in the UK or Canada, demonstrate a political decision to prioritize collective well-being over market-driven models. Conversely, countries with privatized healthcare often reflect a belief in individual responsibility and free-market principles. This divergence highlights how public services are both a tool and a reflection of political ideology.

Consider education, another critical public service, where the state’s role extends beyond literacy to shaping future generations. In Finland, the government invests heavily in teacher training and equitable school funding, resulting in one of the world’s highest-performing education systems. This example underscores the importance of strategic investment and policy design. However, the provision of education is not without challenges. In many developing nations, inadequate infrastructure and funding disparities between urban and rural areas create systemic inequalities. Policymakers must address these gaps by allocating resources based on need, not political expediency, to ensure education serves as a great equalizer.

Infrastructure, often overlooked, is a silent enabler of economic and social progress. Roads, bridges, and public transportation are not just physical assets but political outputs that determine accessibility and opportunity. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, for example, is a massive infrastructure project with geopolitical implications, showcasing how infrastructure can be both a domestic necessity and a foreign policy tool. Locally, the maintenance of infrastructure requires foresight and consistent funding. Neglecting this leads to disasters like the 2018 Morandi Bridge collapse in Italy, a stark reminder of the consequences of underinvestment. Governments must adopt long-term planning and transparent funding mechanisms to avoid such tragedies.

Social welfare programs, the fourth pillar of public services, are a litmus test for a state’s commitment to social justice. Programs like Sweden’s comprehensive welfare system provide a safety net that reduces poverty and inequality, fostering social cohesion. However, these programs are not without trade-offs. High taxation and potential disincentives to work are common criticisms. Striking a balance requires evidence-based policymaking, such as conditional cash transfers in Brazil’s Bolsa Família, which tie benefits to school attendance and health check-ups. Such programs demonstrate that social welfare can be both compassionate and pragmatic, addressing immediate needs while promoting long-term self-sufficiency.

In conclusion, the provision of public services is a multifaceted political output that shapes societies and reflects governance philosophies. Healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social welfare are not isolated sectors but interconnected systems that require holistic planning and sustained investment. By studying successful models and learning from failures, governments can design public services that are equitable, efficient, and responsive to citizens’ needs. The challenge lies in balancing ideological commitments with practical realities, ensuring that public services remain a force for progress, not division.

Inflation's Dual Nature: Economic Forces vs. Political Decisions

You may want to see also

Economic Measures: Fiscal and monetary policies, taxation, and trade agreements shaping economies

Governments wield economic measures as their scalpel, carving the contours of national prosperity. Fiscal policy, the deliberate manipulation of government spending and taxation, acts as a direct lever. During recessions, deficit spending on infrastructure or social programs injects stimulus, while surpluses during booms cool overheated economies. Monetary policy, controlled by central banks, adjusts the money supply and interest rates. Lower rates encourage borrowing and investment, fueling growth, while higher rates curb inflation. These tools, when synchronized, can stabilize economies, but their effectiveness hinges on timing, dosage, and coordination.

Consider the 2008 financial crisis. Central banks slashed interest rates to near zero, while governments unleashed massive fiscal stimulus packages. The US, for instance, allocated $787 billion in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, combining tax cuts, infrastructure spending, and aid to states. This coordinated effort averted a deeper depression, demonstrating the power of economic measures in crisis management. However, such interventions carry risks: excessive debt accumulation can burden future generations, and prolonged low rates may inflate asset bubbles.

Taxation, another critical economic measure, redistributes wealth and funds public services. Progressive tax systems, where higher incomes face steeper rates, aim to reduce inequality. For example, Nordic countries like Sweden and Denmark impose top marginal rates exceeding 50%, funding extensive welfare states. Conversely, flat tax systems, as in Estonia, prioritize simplicity and economic efficiency. Trade agreements, such as the USMCA or the EU’s single market, reshape economies by lowering tariffs, harmonizing regulations, and fostering cross-border investment. NAFTA, for instance, tripled trade between the US, Canada, and Mexico but also displaced manufacturing jobs in certain sectors, illustrating the dual-edged nature of such pacts.

Crafting effective economic measures requires precision. Fiscal policy must balance short-term stimulus with long-term sustainability. Monetary policy demands vigilance against inflation and deflation. Taxation should align with societal values while minimizing economic distortions. Trade agreements must balance openness with protections for vulnerable industries. For instance, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) included provisions for labor and environmental standards, addressing criticisms of earlier agreements. Policymakers must also consider global interdependencies: a country’s monetary easing can trigger currency devaluations abroad, sparking trade tensions.

Ultimately, economic measures are not neutral tools but reflections of political priorities. Expansionary policies may prioritize growth over debt concerns, while austerity measures emphasize fiscal discipline, often at the expense of social programs. Trade agreements can either entrench corporate interests or promote equitable development. The challenge lies in aligning these measures with broader goals—whether reducing inequality, fostering innovation, or ensuring environmental sustainability. As economies evolve, so too must the strategies shaping them, demanding adaptability, foresight, and a commitment to the public good.

Raising Polite Kids: Simple Strategies for Teaching Manners and Respect

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

Foreign Relations: Diplomatic actions, treaties, and international alliances influencing global standing

Diplomatic actions, treaties, and international alliances are the backbone of a nation’s foreign relations, shaping its global standing in profound ways. Consider the 2015 Paris Agreement, a treaty that united 196 countries in combating climate change. This example illustrates how a single accord can elevate a nation’s reputation as a global leader while fostering cooperation on critical issues. Such actions are not merely symbolic; they create binding commitments that influence economic, environmental, and security policies worldwide.

To effectively leverage diplomatic actions, nations must prioritize strategic negotiation and relationship-building. For instance, the U.S.-Japan alliance, formalized through the 1960 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, has provided both countries with military and economic stability for over six decades. This alliance demonstrates the long-term benefits of fostering trust and mutual interests. When engaging in diplomacy, leaders should focus on clear objectives, such as securing trade agreements or resolving conflicts, while remaining adaptable to shifting global dynamics.

However, forming international alliances is not without risks. The 2003 Iraq War coalition, led by the U.S. and the U.K., highlights how alliances can strain relationships if perceived as unilateral or unjustified. Nations must carefully weigh the potential consequences of their actions, ensuring alignment with international norms and domestic public opinion. A misstep in diplomacy can erode trust, damage reputations, and isolate a country on the global stage.

Practical tips for enhancing diplomatic efforts include investing in cultural exchanges, which foster goodwill and understanding. For example, Germany’s cultural diplomacy, exemplified by the Goethe-Institut, has strengthened its soft power by promoting language, arts, and education globally. Additionally, nations should utilize multilateral platforms like the United Nations to amplify their voice and collaborate on shared challenges. By combining bilateral and multilateral strategies, countries can maximize their influence while maintaining flexibility in an ever-changing world.

In conclusion, foreign relations are a dynamic political output that requires careful planning, strategic execution, and continuous evaluation. Diplomatic actions, treaties, and alliances are not just tools of statecraft but investments in a nation’s future. By learning from historical successes and failures, countries can navigate the complexities of global politics, ensuring their standing remains robust and resilient.

Unveiling Power: The Sharp Impact of Political Satire Explained

You may want to see also

Social Programs: Initiatives addressing inequality, poverty, and community development for societal well-being

Social programs are the backbone of a society's commitment to equity and collective prosperity. They are not mere handouts but strategic investments in human capital, designed to break the cycles of inequality and poverty that undermine social cohesion. Consider the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the United States, which provides a refundable tax credit to low-to-moderate-income working individuals and families. Studies show that for every $1 spent on the EITC, the economy sees a return of $1.50–$2.00 through increased consumer spending and reduced healthcare costs. This is a prime example of how targeted financial support can stimulate both individual and macroeconomic growth.

Designing effective social programs requires a nuanced understanding of the communities they serve. Take Brazil’s Bolsa Família, a conditional cash transfer program that provides stipends to families in poverty, contingent on children’s school attendance and health check-ups. Since its inception in 2003, it has lifted an estimated 20 million Brazilians out of extreme poverty. The program’s success lies in its dual focus: immediate financial relief paired with long-term human capital development. For policymakers, the takeaway is clear: combine short-term aid with mechanisms that foster self-sufficiency. When implementing similar initiatives, ensure eligibility criteria are clear, application processes are accessible, and benefits are indexed to inflation to maintain their purchasing power over time.

Critics often argue that social programs create dependency, but evidence suggests otherwise. Take the case of Finland’s basic income experiment, where 2,000 unemployed citizens received €560 monthly, no strings attached. Contrary to fears, recipients reported reduced stress, improved mental health, and increased participation in the labor market. The key here is not the universality of the program but its ability to provide a safety net that empowers individuals to take risks—whether starting a business, upskilling, or transitioning to more stable employment. For governments considering such models, start with pilot programs to test scalability and adjust based on real-world outcomes.

Community development is another critical pillar of social programs, often overlooked in favor of direct financial aid. The Harlem Children’s Zone in New York City is a pioneering example, offering a pipeline of services from prenatal care to college preparation within a 97-block area. By addressing systemic barriers holistically—education, health, housing—the initiative has seen a 50% increase in college enrollment rates among participants. Such place-based interventions require significant upfront investment but yield dividends in reduced crime, improved public health, and stronger local economies. When replicating this model, engage local leaders early, tailor services to community needs, and measure success not just by metrics but by lived experiences.

Finally, the sustainability of social programs hinges on their political and financial viability. Take the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, a publicly funded healthcare system that provides universal coverage. While celebrated for its inclusivity, the NHS faces chronic underfunding and workforce shortages. To avoid such pitfalls, governments must ensure programs are adequately resourced, with diversified funding streams and mechanisms for public accountability. For instance, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, financed by oil revenues, supports its extensive welfare state. By adopting similar long-term financing strategies, nations can safeguard social programs against economic downturns and shifting political winds, ensuring they remain a cornerstone of societal well-being.

Political Machines: Unseen Benefits in Local Governance and Community Development

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political output refers to the tangible results or actions produced by a political system, government, or institution, such as laws, policies, regulations, or public services, aimed at addressing societal needs or achieving specific goals.

Political outputs are the immediate products of government actions (e.g., passing a law), while political outcomes are the long-term effects or changes in society resulting from those actions (e.g., reduced crime rates due to the law).

Political outputs are typically created by governments, legislative bodies, policymakers, and public institutions, often in collaboration with stakeholders, interest groups, and citizens.

Political outputs are crucial in a democracy as they reflect the government's responsiveness to citizen needs, ensure accountability, and demonstrate the effectiveness of policies in addressing public issues.