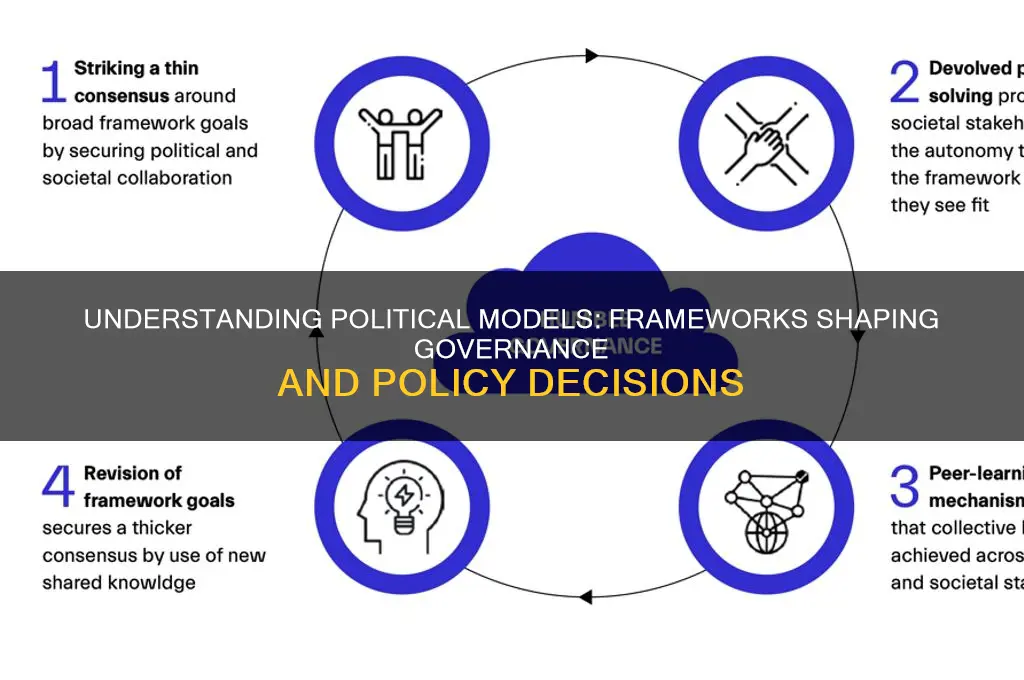

A political model is a theoretical framework or conceptual structure used to understand, analyze, and explain political systems, processes, and behaviors. It serves as a tool for scholars, policymakers, and citizens to interpret complex political phenomena by simplifying and organizing key elements such as power distribution, governance structures, decision-making mechanisms, and citizen participation. Political models can range from normative ideals, like democracy or authoritarianism, to descriptive frameworks that map real-world political dynamics. By providing a lens through which to examine political realities, these models facilitate comparisons across systems, predict outcomes, and inform strategies for reform or stability, making them essential in the study and practice of politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A theoretical framework or conceptual tool used to analyze, understand, or predict political systems, behaviors, or outcomes. |

| Purpose | To simplify complex political phenomena, guide research, and inform policy-making. |

| Types | Normative (ideal systems), Empirical (observable systems), Explanatory (causal relationships). |

| Key Components | Actors (e.g., individuals, groups, institutions), Structures (e.g., government, economy), Processes (e.g., elections, policy-making). |

| Examples | Democracy, Authoritarianism, Pluralism, Elitism, Marxism, Liberalism, Realism. |

| Methodology | Uses qualitative and quantitative methods, case studies, comparative analysis, and statistical modeling. |

| Scope | Can be global (e.g., international relations), national (e.g., governance), or local (e.g., community politics). |

| Dynamic Nature | Evolves with changes in political landscapes, technological advancements, and societal shifts. |

| Criticisms | Often oversimplifies reality, may be biased, and can struggle to account for unpredictability in politics. |

| Applications | Academic research, political strategy, policy development, and public discourse. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Democracy: System of government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives

- Authoritarianism: Centralized power with limited political freedoms and opposition suppression

- Federalism: Division of power between central and regional governments, ensuring shared authority

- Socialism: Economic system advocating public ownership of resources and equitable wealth distribution

- Anarchy: Absence of hierarchical governance, promoting self-organization and voluntary cooperation

Democracy: System of government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives

Democracy, as a political model, hinges on the principle of rule by the people. This foundational idea manifests in two primary forms: direct democracy, where citizens participate directly in decision-making, and representative democracy, where elected officials act on their behalf. Each variant carries distinct mechanisms and implications, shaping governance in ways that reflect societal values and practical realities. For instance, Switzerland’s frequent use of referendums exemplifies direct democracy, while the United States’ congressional system illustrates representative democracy. Understanding these structures is crucial for evaluating how power is distributed and exercised within a polity.

Implementing democracy requires careful consideration of procedural safeguards to ensure fairness and inclusivity. Elections, a cornerstone of representative democracy, must be free, fair, and periodic to maintain legitimacy. This involves transparent voter registration, impartial media coverage, and robust mechanisms to prevent fraud. In direct democracies, the challenge lies in scaling participation to accommodate diverse populations. For example, digital platforms can facilitate broader engagement, but they must be accessible to all age groups and socioeconomic strata to avoid skewing outcomes. Practical steps include investing in civic education and ensuring technological infrastructure supports equitable participation.

A persuasive argument for democracy lies in its capacity to foster accountability and responsiveness. Elected representatives, knowing their tenure depends on public approval, are incentivized to align policies with constituent interests. This dynamic, however, is not without risks. Short electoral cycles can encourage populist decision-making over long-term strategic planning. To mitigate this, democracies often incorporate checks and balances, such as independent judiciaries or multi-tiered governance systems. For instance, Germany’s federal structure distributes power between the national government and states, reducing the risk of centralized authority abuse.

Comparatively, democracy’s strength in adapting to societal changes contrasts with more rigid political models. Unlike authoritarian regimes, which prioritize stability through control, democracies thrive on debate and compromise. This adaptability, however, can lead to slower decision-making, particularly in times of crisis. A comparative analysis of democratic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic reveals varying degrees of success, influenced by factors like leadership trust and institutional resilience. Democracies that balanced swift action with public consultation, such as New Zealand, demonstrated the model’s potential when effectively managed.

Ultimately, democracy’s enduring appeal lies in its alignment with human aspirations for self-determination and equality. However, its success depends on active citizen engagement and robust institutional design. Practical tips for strengthening democratic systems include encouraging voter turnout through accessible polling stations, promoting media literacy to combat misinformation, and fostering dialogue across ideological divides. By addressing these elements, democracies can better fulfill their promise of governance by and for the people, adapting to contemporary challenges while preserving core principles.

Is ABC Politically Biased? Uncovering Media Slant and Objectivity

You may want to see also

Authoritarianism: Centralized power with limited political freedoms and opposition suppression

Authoritarianism thrives on the concentration of power in a single entity—be it an individual, a party, or a junta—with minimal checks and balances. This model systematically curtails political freedoms, such as free speech, assembly, and the press, to maintain control. Opposition is not merely discouraged but actively suppressed through censorship, surveillance, and often, state-sanctioned violence. Examples range from historical regimes like Franco’s Spain to contemporary systems in North Korea and Belarus. The hallmark is the absence of meaningful citizen participation in governance, replaced by a top-down hierarchy where dissent is equated with disloyalty.

To understand authoritarianism’s mechanics, consider its reliance on three pillars: ideological uniformity, security apparatus dominance, and economic dependency. Ideologically, regimes often promote a singular narrative—nationalism, religious orthodoxy, or revolutionary purity—to justify their authority. Security forces, from police to intelligence agencies, are weaponized to monitor and neutralize threats. Economically, the state controls key resources, fostering dependency and using patronage to reward loyalty. For instance, in modern-day Russia, state-controlled media amplifies Kremlin narratives, while oligarchs tied to the regime ensure economic alignment with political goals.

Implementing authoritarianism often follows a playbook: first, dismantle independent institutions like courts and media; second, create a cult of personality or party infallibility; third, use external threats (real or imagined) to rally support. Take Egypt post-2013, where President Sisi’s regime justified crackdowns on dissent by framing opposition as a threat to national stability. Similarly, China’s use of "social credit systems" and mass surveillance in Xinjiang exemplifies how technology can be harnessed to enforce conformity. These steps, while effective in consolidating power, come at the cost of individual liberties and societal pluralism.

Critics argue authoritarianism’s efficiency is a myth, pointing to its long-term instability. Without mechanisms for peaceful power transition or accountability, regimes often collapse violently, as seen in the Arab Spring. However, proponents claim it ensures stability in times of crisis, citing Singapore’s rapid development under Lee Kuan Yew’s semi-authoritarian rule. The reality lies in context: while authoritarianism can deliver short-term order, its sustainability depends on factors like economic growth, external legitimacy, and the regime’s ability to adapt without loosening control.

For those studying or confronting authoritarianism, focus on its vulnerabilities: information flow, international pressure, and internal fractures. Grassroots movements, like Hong Kong’s 2019 protests, highlight the power of decentralized resistance. Externally, sanctions and diplomatic isolation can weaken regimes reliant on global legitimacy. Internally, elite defections or economic crises can expose the system’s fragility. Understanding these dynamics is key to both analyzing and challenging authoritarian models, offering insights into how centralized power can be both wielded and undermined.

Kumbaya Politics: Understanding the Call for Unity in Divisive Times

You may want to see also

Federalism: Division of power between central and regional governments, ensuring shared authority

Federalism is a political model that divides power between a central authority and regional governments, creating a system of shared governance. This structure is not merely a theoretical concept but a practical framework adopted by numerous countries, including the United States, Germany, and India. At its core, federalism aims to balance unity with diversity, allowing regional entities to address local needs while maintaining a cohesive national identity. This dual authority ensures that neither level of government becomes overly dominant, fostering a dynamic equilibrium.

Consider the implementation of federalism in the United States, where the Constitution delineates powers between the federal government and the states. For instance, while the federal government handles national defense and foreign policy, states retain authority over education, healthcare, and infrastructure. This division is not rigid; the Tenth Amendment reserves powers not granted to the federal government to the states or the people, illustrating the model’s flexibility. Such a system encourages innovation at the state level, as seen in California’s environmental policies or Texas’s economic strategies, while ensuring national cohesion on critical issues.

However, federalism is not without challenges. The interplay between central and regional authorities can lead to conflicts over jurisdiction, as evidenced by debates over healthcare reform or gun control in the U.S. These disputes often require judicial intervention, highlighting the need for clear constitutional guidelines and mechanisms for dispute resolution. For nations considering federalism, it is crucial to establish robust institutional frameworks that define the scope of powers and provide avenues for collaboration and conflict resolution.

A persuasive argument for federalism lies in its ability to accommodate cultural and regional diversity. In India, for example, federalism allows states like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu to preserve their distinct languages and traditions while participating in a unified nation. This model fosters inclusivity, reducing the risk of secessionist movements by giving regions a voice in governance. For policymakers, federalism offers a blueprint for managing diverse populations, provided there is a commitment to equitable resource distribution and respect for regional autonomy.

In practice, implementing federalism requires careful calibration. Nations transitioning to this model should prioritize constitutional clarity, ensuring that the division of powers is explicit and enforceable. Additionally, fostering intergovernmental cooperation through councils or joint committees can mitigate conflicts. For instance, Canada’s Council of the Federation serves as a platform for provincial premiers to collaborate with the federal government. Such mechanisms are essential for maintaining the balance of power and ensuring that federalism fulfills its promise of shared authority and effective governance.

Understanding Political Incorrectness: Origins, Impact, and Modern Controversies Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Socialism: Economic system advocating public ownership of resources and equitable wealth distribution

Socialism, as a political and economic model, challenges the traditional capitalist framework by prioritizing collective ownership and equitable distribution of wealth. At its core, socialism advocates for public or cooperative ownership of resources, means of production, and key industries, shifting control from private hands to the community or state. This model aims to reduce economic inequality by ensuring that wealth and resources are distributed more fairly among all members of society, rather than concentrated in the hands of a few.

Consider the practical implementation of socialism in countries like Sweden and Norway, often cited as examples of democratic socialism. These nations combine market economies with robust public sectors, where healthcare, education, and social services are universally accessible. For instance, in Sweden, approximately 50% of GDP is allocated to public spending, funding extensive welfare programs. This approach demonstrates how socialism can function within a democratic framework, balancing economic efficiency with social equity. However, critics argue that high taxation and extensive regulation can stifle innovation and individual initiative, highlighting the need for careful calibration in socialist policies.

To adopt socialist principles, policymakers must focus on three key steps: nationalizing or cooperatively managing essential industries (e.g., energy, transportation), implementing progressive taxation to fund social programs, and fostering worker cooperatives to decentralize economic power. For example, in Barcelona, Spain, the city government has supported the growth of over 1,000 worker cooperatives, providing jobs and economic stability to marginalized communities. Yet, caution is necessary; abrupt nationalization without clear management strategies can lead to inefficiency, as seen in some post-colonial African nations in the 1960s.

A persuasive argument for socialism lies in its potential to address systemic inequalities. In the U.S., the top 1% owns nearly 35% of the country’s wealth, a disparity that socialism seeks to rectify. By redistributing resources and ensuring access to essentials like healthcare and education, socialism can create a more level playing field. However, this requires a shift in societal values, prioritizing collective well-being over individual accumulation. For individuals, supporting local cooperatives, advocating for progressive policies, and engaging in community-driven initiatives are tangible ways to contribute to socialist ideals.

In conclusion, socialism offers a distinct political model centered on public ownership and equitable wealth distribution. While its implementation varies globally, its core principles provide a framework for addressing economic inequality. By learning from successful examples, avoiding historical pitfalls, and fostering community engagement, socialism can serve as a viable alternative to capitalist systems, though its success depends on thoughtful adaptation to local contexts and societal needs.

Politics in Love: Do Ideological Differences Break or Make Relationships?

You may want to see also

Anarchy: Absence of hierarchical governance, promoting self-organization and voluntary cooperation

Anarchy, often misunderstood as chaos, is fundamentally about the absence of hierarchical governance, emphasizing self-organization and voluntary cooperation. Unlike systems where authority is imposed from above, anarchy relies on individuals and communities to structure their own interactions and resolve conflicts collaboratively. This model challenges the notion that order requires centralized control, instead positing that human societies can thrive through mutual aid and decentralized decision-making.

Consider the example of the Spanish Revolution of 1936, where anarchist principles were applied on a large scale. Workers collectivized factories, and villages organized themselves through voluntary assemblies. This period demonstrated that self-governance could lead to efficient resource distribution and social cohesion, even in the midst of war. Such historical instances highlight the potential of anarchy to foster equality and autonomy, provided communities are committed to shared goals and open communication.

Implementing an anarchist model requires a shift in mindset from reliance on external authority to trust in collective capability. Practical steps include fostering local networks, encouraging participatory decision-making, and developing conflict resolution mechanisms that prioritize consensus. For instance, in modern co-housing communities, residents often use consensus-based meetings to manage shared spaces and resources, proving that voluntary cooperation can work in everyday settings. However, this approach demands patience, as building trust and skills for self-organization takes time.

Critics argue that anarchy lacks the structure needed to address large-scale issues like defense or infrastructure. Yet, examples like the Kurdish region of Rojava, which operates on democratic confederalist principles inspired by anarchism, show how decentralized systems can manage complex challenges. Rojava’s model combines local autonomy with regional coordination, offering a blueprint for balancing self-organization with collective action. This suggests that anarchy is not about eliminating organization but reimagining it without hierarchy.

Ultimately, anarchy is not a utopian ideal but a practical framework for empowering individuals and communities. By rejecting imposed authority and embracing voluntary cooperation, it challenges us to rethink how societies can function. While not without challenges, its emphasis on self-organization offers a path toward more equitable and participatory political systems, proving that order and freedom can coexist without hierarchy.

Understanding Political Achievement: Impact, Legacy, and Societal Transformation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political model is a theoretical framework or conceptual structure used to understand, analyze, or predict political systems, behaviors, or outcomes. It simplifies complex political phenomena to explain how power is distributed, exercised, and contested within societies.

Examples of political models include democracy, authoritarianism, totalitarianism, oligarchy, and anarchism. Each model represents a distinct approach to governance, decision-making, and the relationship between the state and its citizens.

Political models are important because they provide a lens through which to study and compare different political systems. They help scholars, policymakers, and citizens understand the underlying principles of governance, identify strengths and weaknesses, and evaluate the potential consequences of political decisions.