A political machine is a powerful and often controversial organization that operates within the framework of a political party, typically at the local or state level, to maintain control over political processes and resources. Characterized by a hierarchical structure, patronage systems, and a focus on delivering tangible benefits to supporters, these machines thrive on reciprocal relationships where votes and loyalty are exchanged for jobs, contracts, or favors. Historically, they have played a significant role in urban politics, particularly in the United States, by mobilizing voters, shaping elections, and influencing policy in ways that prioritize the interests of the machine’s leadership. While critics argue that political machines can foster corruption and undermine democratic principles, proponents highlight their ability to provide services and representation to marginalized communities. Understanding the mechanics and impact of political machines is essential for grasping the complexities of power, governance, and civic engagement in modern political systems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political machine is a political organization in which an authoritative boss or small group commands the support of a corps of supporters and businesses (usually campaign workers), who receive rewards for their efforts. |

| Historical Context | Originated in the 19th century, particularly in urban areas of the United States, such as Tammany Hall in New York City. |

| Key Figures | Bosses or leaders who wield significant control over the organization, e.g., Boss Tweed, George Washington Plunkitt. |

| Structure | Hierarchical, with a clear chain of command from the boss to ward heelers (local operatives) and down to precinct captains and workers. |

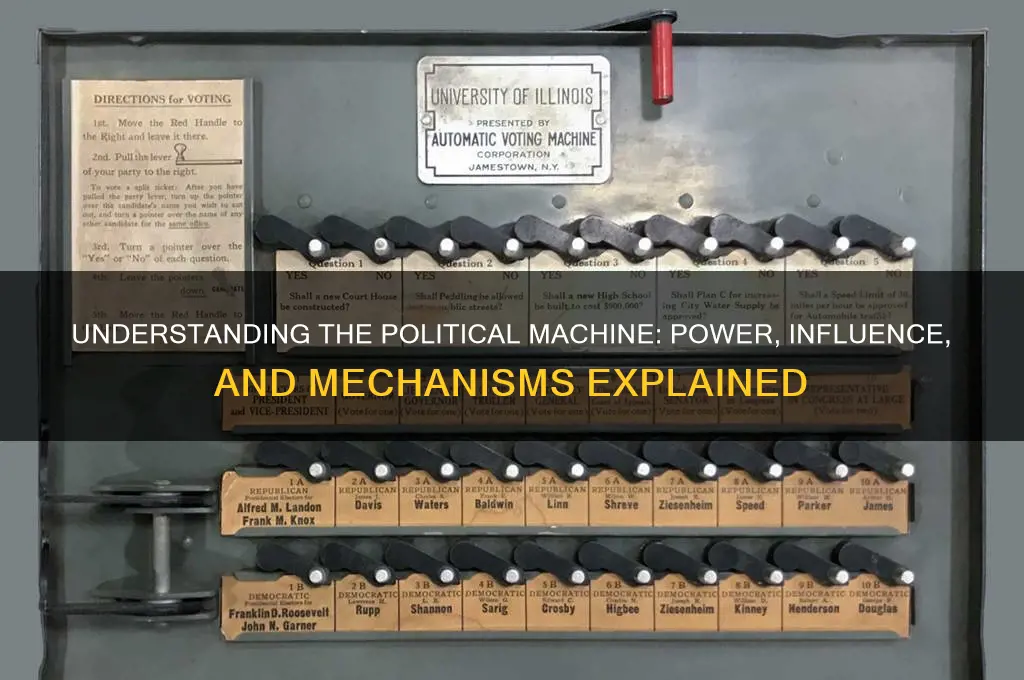

| Methods | Patronage (distributing government jobs and contracts), voter mobilization, and sometimes voter fraud or intimidation. |

| Goals | To maintain political power, control elections, and secure benefits for the machine and its supporters. |

| Support Base | Often relies on immigrant communities, working-class voters, and those in need of social services or employment. |

| Criticisms | Accused of corruption, nepotism, and undermining democratic processes by prioritizing loyalty over merit or public interest. |

| Modern Examples | While less prevalent today, remnants exist in certain local or regional political organizations, often tied to longstanding party dominance. |

| Legal Status | Many practices associated with political machines, such as patronage, have been restricted by civil service reforms and anti-corruption laws. |

| Impact | Historically played a significant role in urban development, social welfare, and the integration of immigrant communities into political life. |

Explore related products

$20.98 $39

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Brief history and core concept of the political machine in governance

- Structure and Hierarchy: Organization, leadership, and roles within a political machine system

- Methods of Control: Tactics like patronage, voter mobilization, and resource distribution

- Impact on Democracy: Influence on elections, policy-making, and public trust in institutions

- Historical Examples: Case studies of notable political machines (e.g., Tammany Hall)

Definition and Origins: Brief history and core concept of the political machine in governance

A political machine is a system of political organization that relies on hierarchical structures, patronage, and reciprocal relationships to maintain power and control. Emerging in the 19th century, particularly in urban areas of the United States, these machines were often associated with city bosses who wielded significant influence over local politics. The core concept revolves around the exchange of resources—such as jobs, contracts, or favors—for political loyalty and votes, creating a network of dependency that sustains the machine’s dominance.

Consider Tammany Hall in New York City, one of the most notorious examples. Led by figures like Boss Tweed, it operated by providing services to immigrants in exchange for their electoral support. This model was replicated in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, where machines like the Daley machine and the Vare brothers’ organization thrived. These entities were not merely corrupt systems but also functional governance structures that filled gaps in social services, particularly in immigrant communities neglected by formal institutions.

Analyzing the origins reveals a symbiotic relationship between machines and the socio-economic conditions of their time. Industrialization and urbanization created overcrowded cities with diverse, often marginalized populations. Political machines capitalized on this by offering tangible benefits—jobs, housing, or legal assistance—in exchange for votes. This transactional approach to politics was both a product of and a response to the era’s challenges, blending pragmatism with opportunism.

However, the rise of political machines also underscores a cautionary tale about the dangers of centralized, unaccountable power. While they provided immediate solutions to pressing needs, they often undermined democratic principles by prioritizing loyalty over merit and perpetuating corruption. The eventual decline of these machines in the mid-20th century, due to reforms and public backlash, highlights the tension between efficiency and ethical governance.

In practice, understanding political machines offers insights into modern political dynamics. While overt machines have largely disappeared, their legacy persists in clientelistic networks and patronage systems worldwide. For instance, in developing democracies, politicians often distribute resources like food or cash during elections to secure votes. Recognizing these patterns allows for more informed critiques of contemporary governance and the ongoing struggle to balance power, accountability, and public welfare.

Understanding Political Policy Making: Processes, Players, and Impact

You may want to see also

Structure and Hierarchy: Organization, leadership, and roles within a political machine system

A political machine operates as a highly structured, hierarchical system designed to consolidate power and deliver results through disciplined organization. At its core, the structure is pyramidal, with a clear chain of command that ensures loyalty and efficiency. The boss, often a charismatic or influential figure, sits at the apex, making key decisions and maintaining ultimate control. Below them are lieutenants, trusted operatives who manage specific territories or functions, such as fundraising, voter mobilization, or patronage distribution. These lieutenants oversee precinct captains, the foot soldiers who interact directly with communities, ensuring grassroots support and delivering on promises. Each role is defined by its proximity to power and its ability to execute the machine’s agenda, creating a system where every member knows their place and purpose.

Leadership within a political machine is less about ideology and more about pragmatism and control. The boss’s primary skill lies in balancing competing interests, rewarding loyalty, and punishing dissent. They must maintain a delicate equilibrium between external demands—such as voter expectations or donor pressures—and internal dynamics, like power struggles among lieutenants. Effective leaders use patronage as a tool, distributing jobs, contracts, or favors to solidify their network. For instance, a precinct captain might secure a city maintenance job for a constituent in exchange for guaranteed votes. This transactional approach ensures that every member of the hierarchy has a stake in the machine’s success, fostering cohesion and discipline.

Roles within the system are specialized and interdependent, each contributing to the machine’s overarching goals. Precinct captains, often local figures with deep community ties, act as the machine’s eyes and ears, identifying needs and mobilizing voters. They are the bridge between the machine and the public, ensuring that promises made are promises kept. Above them, lieutenants handle logistics, such as coordinating campaigns or managing finances, while also mediating conflicts within their domains. At the top, the boss focuses on strategy, forging alliances with external power brokers and navigating broader political landscapes. This division of labor minimizes redundancy and maximizes efficiency, allowing the machine to operate as a well-oiled mechanism.

To understand the hierarchy’s effectiveness, consider the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York. Boss Tweed, at the helm, controlled a vast network of operatives who delivered services to immigrants in exchange for votes, ensuring Democratic dominance. Precinct captains like "Big Tim" Sullivan built personal empires by catering to their constituents’ needs, from legal aid to holiday turkeys. This model illustrates how a rigid hierarchy, combined with clear roles and transactional leadership, can sustain political power over decades. However, such systems are vulnerable to corruption, as the lines between public service and personal gain often blur.

For those studying or engaging with political machines, understanding their structure is crucial. Start by identifying the boss and their key lieutenants, as these figures dictate the machine’s direction and priorities. Analyze how roles are assigned and rewards distributed, as this reveals the system’s internal logic. For instance, if precinct captains are rewarded based on voter turnout, the machine prioritizes mobilization over policy advocacy. Finally, assess the hierarchy’s resilience: how does it adapt to challenges like scandals or shifting demographics? By dissecting these elements, one can grasp not only how a political machine functions but also its potential strengths and weaknesses.

Mastering Polite Expressions: Enhancing Communication with Gracious Language

You may want to see also

Methods of Control: Tactics like patronage, voter mobilization, and resource distribution

Political machines thrive on control, and their methods are as varied as they are effective. Three key tactics stand out: patronage, voter mobilization, and resource distribution. Each serves a distinct purpose, yet all converge on the same goal—securing and maintaining power. Patronage, the oldest of these methods, involves the strategic allocation of jobs, contracts, and favors to loyal supporters. This creates a network of dependents who, in turn, become foot soldiers for the machine. Voter mobilization, on the other hand, is about ensuring that these loyalists—and only these loyalists—turn out on election day. Resource distribution, often disguised as public service, cements the machine’s legitimacy by providing tangible benefits to constituents, fostering a sense of obligation and loyalty.

Consider patronage as the backbone of the political machine. It operates on a simple principle: reward loyalty with opportunity. For instance, a machine might appoint a supporter as a city clerk or grant a lucrative construction contract to a sympathetic business owner. These appointments and contracts are rarely based on merit but on unwavering allegiance. The machine’s leaders become de facto gatekeepers of opportunity, ensuring that those who benefit remain indebted. This system is self-perpetuating; the more people rely on the machine for their livelihoods, the harder they work to keep it in power. However, this tactic is not without risk. Mismanagement or corruption can lead to public backlash, as seen in the downfall of Tammany Hall in New York City, where patronage scandals eroded public trust.

Voter mobilization is the machine’s offensive strategy, ensuring that its base is not just loyal but active. This involves a combination of grassroots organizing and logistical precision. Machines often employ precinct captains—local leaders who know their neighborhoods intimately—to identify, persuade, and transport voters to the polls. These captains use door-to-door canvassing, phone banking, and even social events to rally support. In some cases, machines have been known to employ more aggressive tactics, such as voter intimidation or fraud, though these are riskier and less sustainable. The key is to create a sense of urgency and importance around voting, framing it as a duty to the community or a means of self-preservation. For example, during the 19th century, machines in Chicago would offer free food and transportation to voters, ensuring high turnout in their strongholds.

Resource distribution is the machine’s defensive strategy, aimed at building goodwill and softening resistance. This tactic involves directing public resources—such as funding for schools, infrastructure, or social services—to areas that support the machine. By doing so, the machine creates a narrative of effectiveness and care, even if the distribution is uneven or politically motivated. For instance, a machine might prioritize road repairs in a loyal neighborhood while neglecting others. This not only rewards supporters but also discourages opposition by demonstrating the machine’s ability to deliver results. However, this approach requires careful calibration. Overly blatant favoritism can alienate neutral or opposing groups, while too little can erode the machine’s base.

In practice, these tactics are often used in tandem, creating a multifaceted system of control. Patronage builds the machine’s internal structure, voter mobilization ensures its electoral dominance, and resource distribution solidifies its external legitimacy. Together, they form a powerful trifecta that can sustain a machine for decades. Yet, their effectiveness depends on context. In areas with high poverty or limited opportunities, patronage and resource distribution can be particularly potent. Conversely, in more affluent or politically aware communities, these tactics may face greater scrutiny. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for both those seeking to build a machine and those aiming to dismantle one. The takeaway is clear: control in a political machine is not just about power—it’s about the strategic allocation of resources, opportunities, and influence.

Understanding Political Cults: Definition, Tactics, and Real-World Examples

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on Democracy: Influence on elections, policy-making, and public trust in institutions

Political machines, historically rooted in localized networks of patronage and control, have evolved into sophisticated systems that wield significant influence over democratic processes. Their impact on elections is particularly pronounced, as they often mobilize voters through targeted outreach, resource distribution, and, in some cases, coercion. For instance, machines may deploy precinct captains to ensure high turnout in specific neighborhoods, leveraging personal relationships to sway outcomes. While this can increase participation, it also raises concerns about the autonomy of individual voters, as decisions may be driven by loyalty to the machine rather than independent judgment. Such practices blur the line between civic engagement and manipulation, undermining the principle of free and fair elections.

In policy-making, political machines can act as double-edged swords. On one hand, they streamline decision-making by consolidating power and ensuring legislative efficiency. For example, a machine-backed administration might swiftly pass infrastructure bills by rallying loyal officials. On the other hand, this efficiency often comes at the expense of transparency and inclusivity. Policies may prioritize the interests of machine insiders or their financial backers, sidelining broader public needs. This dynamic fosters a perception of governance as an exclusive club, alienating citizens who feel their voices are ignored. Over time, such exclusion erodes trust in democratic institutions, as people question whether the system truly serves them.

Public trust in institutions is perhaps the most fragile casualty of political machine influence. When machines dominate local or national politics, they create an opaque layer between citizens and their representatives. Scandals involving corruption or favoritism, common in machine-driven systems, further disillusion the public. For instance, the historical Tammany Hall machine in New York City exemplified how patronage networks could distort governance, leading to widespread cynicism. Rebuilding trust requires systemic reforms, such as campaign finance transparency and anti-corruption measures, but these are often resisted by the very machines that benefit from the status quo.

To mitigate the negative impacts of political machines, democracies must adopt proactive measures. Strengthening electoral oversight, such as independent monitoring of voter mobilization efforts, can curb coercive tactics. Policy-making processes should incorporate mechanisms for public input, like participatory budgeting, to ensure decisions reflect collective interests. Additionally, media literacy campaigns can empower citizens to recognize and resist machine-driven narratives. While machines may never disappear entirely, their influence can be balanced by fostering a more informed and engaged electorate, capable of holding institutions accountable. The challenge lies in implementing these reforms without falling prey to the very systems they aim to correct.

Understanding Political Risk Analysis: Strategies for Global Business Success

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: Case studies of notable political machines (e.g., Tammany Hall)

Tammany Hall, the quintessential American political machine, dominated New York City politics for over a century. Operating from the late 18th century until the mid-20th century, it exemplified the machine's core strategy: exchanging favors for votes. Led by figures like Boss Tweed, Tammany Hall controlled patronage jobs, distributed resources to immigrant communities, and mobilized voters through a network of local clubs. While it provided essential services to marginalized groups, it also became synonymous with corruption, using graft and bribery to maintain power. Tammany Hall's rise and fall illustrate the dual nature of political machines: their ability to empower the disenfranchised and their tendency toward systemic abuse.

Across the Atlantic, the Chicago Democratic Machine under Mayor Richard J. Daley offers a comparative study in longevity and local control. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Daley’s machine perfected the art of precinct-level organization, ensuring voter turnout through a combination of patronage and neighborhood loyalty. Unlike Tammany Hall, which relied heavily on immigrant communities, Daley’s machine catered to a broader urban coalition, including African American and working-class white voters. Its success lay in its ability to deliver tangible benefits—jobs, infrastructure, and political representation—while maintaining a tight grip on city council and ward politics. This case highlights how machines adapt to demographic shifts while retaining their core mechanisms of control.

In contrast, the Pendergast Machine in Kansas City during the 1930s demonstrates the intersection of political power and organized crime. Led by Tom Pendergast, the machine thrived during Prohibition, leveraging illegal activities like bootlegging to fund its operations. Pendergast’s control extended to both local and national politics, securing federal contracts and influencing presidential elections. However, his eventual conviction for tax evasion in 1939 exposed the fragility of machines built on illicit foundations. This example underscores the risks of blending political and criminal enterprises, as well as the public backlash that often follows such revelations.

Finally, the Cook County Democratic Party in Illinois, often referred to as the "Daley Machine" in its later iterations, provides a modern lens on the evolution of political machines. Post-Richard J. Daley, the machine adapted to changing political landscapes by embracing data-driven voter outreach and professional campaign management. While patronage remains a tool, the focus has shifted toward policy delivery and coalition-building. This case study reveals how machines can survive by modernizing their tactics while retaining their core function: mobilizing voters and rewarding loyalty. For practitioners, the lesson is clear: adaptability is key to longevity in the ever-changing arena of politics.

Exploring My Political Beliefs: A Personal Perspective on Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political machine is an organization or system in which a political party or group maintains control over government positions and resources through patronage, favoritism, and often corrupt practices, rather than through merit or democratic principles.

A political machine operates by exchanging political support, votes, or loyalty for jobs, contracts, or other benefits. It relies on a hierarchical structure where leaders distribute favors to maintain power and influence over voters and local communities.

Notable examples include Tammany Hall in New York City during the 19th and early 20th centuries, which controlled Democratic Party politics through patronage, and the Daley machine in Chicago, led by Mayor Richard J. Daley, which dominated local politics for decades.

While less prevalent than in the past, political machines still exist in some regions, particularly in local or state politics. They often adapt to modern political systems, using updated methods to maintain control and influence over voters and government resources.