Political linkage refers to the strategic connection or interdependence between different political issues, actors, or institutions, often used to achieve specific policy goals or outcomes. It involves leveraging one issue or relationship to influence or advance another, creating a network of dependencies that can shape political dynamics and decision-making. For example, a government might link trade agreements to human rights improvements, using economic incentives to encourage political reforms. Similarly, political parties may forge alliances by linking their agendas to shared priorities, thereby consolidating support. Understanding political linkage is crucial for analyzing how power is exercised, compromises are made, and policies are negotiated in complex political environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political linkage refers to the connection or interdependence between political actors, issues, or institutions, often used to achieve specific goals or outcomes. |

| Purpose | To build coalitions, secure support, or leverage influence in political decision-making processes. |

| Types | 1. Issue Linkage: Connecting different policy issues to achieve a broader goal. 2. Domestic-International Linkage: Tying domestic political interests to international agreements or actions. 3. Party Linkage: Aligning political parties or factions to form alliances. |

| Examples | 1. Linking trade agreements with environmental standards. 2. Tying foreign aid to human rights improvements. 3. Forming cross-party alliances to pass legislation. |

| Key Actors | Governments, political parties, interest groups, international organizations, and individual leaders. |

| Strategies | Bargaining, negotiation, compromise, and strategic communication to create or strengthen linkages. |

| Challenges | Managing conflicting interests, maintaining credibility, and ensuring long-term sustainability of linkages. |

| Impact | Can lead to policy compromises, expanded political influence, or the resolution of complex issues. |

| Recent Trends | Increased use in global diplomacy, climate policy negotiations, and domestic political campaigns. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Political Linkage: Connecting policies or issues to achieve mutual goals in political negotiations

- Types of Linkage: Issue linkage, domestic-international linkage, and bilateral vs. multilateral linkage examples

- Purpose of Linkage: Enhancing bargaining power, resolving conflicts, and securing agreements in political contexts

- Examples in Diplomacy: Trade deals tied to human rights or environmental policies in international relations

- Challenges of Linkage: Complexity, potential for deadlock, and balancing competing interests in negotiations

Definition of Political Linkage: Connecting policies or issues to achieve mutual goals in political negotiations

Political linkage is a strategic tool in negotiations, where seemingly unrelated policies or issues are connected to create a package deal. Imagine a trade agreement where reduced tariffs on agricultural products are linked to increased environmental protections. This tactic allows negotiators to address multiple priorities simultaneously, leveraging progress in one area to secure concessions in another.

For instance, during the Paris Climate Agreement negotiations, developing nations linked their commitment to emissions reductions with financial aid from developed nations for adaptation and mitigation efforts. This linkage ensured a more comprehensive and equitable outcome, addressing both environmental concerns and economic disparities.

Effectively employing political linkage requires a deep understanding of the interests and priorities of all parties involved. Negotiators must identify issues where there is a potential for mutual gain, even if the issues themselves appear distinct. This involves careful research, strategic thinking, and the ability to build trust and find common ground.

A successful linkage strategy hinges on creating a situation where both sides perceive a "win-win" scenario. For example, linking increased foreign aid to a recipient country with reforms promoting good governance benefits both the donor country's development goals and the recipient's long-term stability.

However, political linkage is not without its risks. Linking issues can complicate negotiations, making them more time-consuming and prone to deadlock. If one issue stalls, the entire package deal can unravel. Additionally, critics argue that linkage can lead to unintended consequences, where concessions in one area come at the expense of progress in another. Careful consideration of potential trade-offs and a commitment to transparency are crucial to mitigate these risks.

Despite these challenges, political linkage remains a powerful tool for achieving ambitious policy goals. By strategically connecting issues, negotiators can overcome stalemates, build consensus, and create solutions that address complex, interconnected problems.

Mastering Polite Pushback: Effective Strategies for Asserting Boundaries Gracefully

You may want to see also

Types of Linkage: Issue linkage, domestic-international linkage, and bilateral vs. multilateral linkage examples

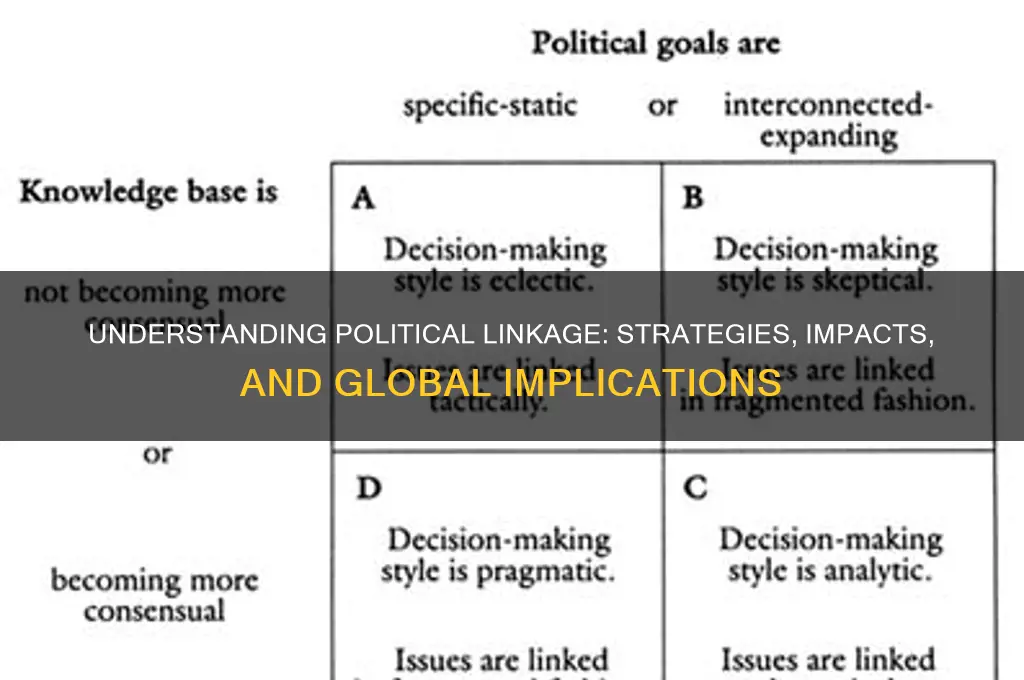

Political linkages are strategic connections made between different issues, levels of governance, or actors to achieve specific goals. Understanding the types of linkage—issue linkage, domestic-international linkage, and bilateral vs. multilateral linkage—is crucial for navigating complex political landscapes. Each type operates differently and serves distinct purposes, offering tools for policymakers, negotiators, and analysts alike.

Issue linkage involves connecting unrelated or loosely related issues to create mutually beneficial outcomes. For instance, during trade negotiations, a country might bundle agricultural subsidies with intellectual property rights, leveraging progress in one area to secure concessions in another. This tactic requires careful calibration: linking too many issues can complicate negotiations, while linking too few may limit leverage. A successful example is the 1972 U.S.-Soviet Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I), where arms control was linked to trade agreements, demonstrating how issue linkage can foster cooperation across contentious domains.

Domestic-international linkage highlights how internal political dynamics influence external policies and vice versa. Domestically, leaders often frame international agreements as solutions to local problems to build public support. For example, climate agreements are frequently marketed as job creators in green industries. Conversely, international pressures can reshape domestic policies; the European Union’s emission standards, for instance, force member states to adopt stricter environmental regulations. This interplay underscores the need for policymakers to align domestic narratives with international commitments, ensuring both credibility and feasibility.

Bilateral vs. multilateral linkage contrasts negotiations between two parties with those involving multiple actors. Bilateral linkages, such as the U.S.-China Phase One trade deal, allow for tailored solutions but risk excluding broader stakeholders. Multilateral linkages, like the Paris Agreement, foster inclusivity but can be cumbersome due to conflicting interests. A practical tip for negotiators: in bilateral settings, focus on mutual gains; in multilateral forums, prioritize coalition-building and compromise. For instance, the World Trade Organization’s success in reducing tariffs globally illustrates the power of multilateral linkage when managed effectively.

In practice, these linkage types are not mutually exclusive but often intersect. For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) combined issue linkage (trade and labor standards), domestic-international linkage (U.S. job concerns shaping negotiations), and multilateral linkage (12 countries coordinating policies). Mastering these linkages requires a nuanced understanding of context, a strategic mindset, and the ability to balance competing priorities. Whether negotiating treaties or crafting policies, recognizing the strengths and limitations of each linkage type can enhance outcomes and mitigate risks.

Does Drizzle Weather Trigger Politoed's SOS Battle Ability?

You may want to see also

Purpose of Linkage: Enhancing bargaining power, resolving conflicts, and securing agreements in political contexts

Political linkage serves as a strategic tool in negotiations, where issues are bundled together to create interdependence and mutual incentives. By connecting seemingly unrelated topics, parties can enhance their bargaining power, as the value of concessions in one area is amplified by gains in another. For instance, during trade negotiations, a country might link market access for agricultural products to reduced tariffs on manufactured goods. This approach forces both sides to consider the broader implications of their decisions, making it harder to walk away without a deal. The key lies in identifying issues that are of varying importance to each party, allowing for a delicate balance of give-and-take.

Resolving conflicts through linkage requires a nuanced understanding of priorities and a willingness to think creatively. In peace negotiations, for example, linking economic aid to disarmament can provide a tangible incentive for warring factions to lay down arms. This method shifts the focus from zero-sum outcomes to mutually beneficial solutions, reducing the likelihood of stalemates. However, success hinges on transparency and trust; if one party perceives the linkage as coercive or unfair, it can backfire, escalating tensions. Practitioners must carefully calibrate the linkage to ensure it addresses underlying grievances while offering a clear path forward.

Securing agreements in political contexts often demands a long-term perspective, as linkage can build momentum for sustained cooperation. Consider climate agreements, where developed nations link financial support for green technologies to commitments from developing countries to reduce emissions. This approach not only addresses immediate concerns but also fosters a framework for ongoing collaboration. To maximize effectiveness, parties should establish clear benchmarks and timelines, ensuring that progress in one area is contingent on advancements in another. This structured approach minimizes the risk of non-compliance and reinforces accountability.

While linkage is a powerful technique, it is not without risks. Over-reliance on this strategy can lead to complexity, making agreements harder to implement. For instance, linking too many issues in a single negotiation can overwhelm participants, diluting focus and delaying outcomes. To mitigate this, prioritize issues based on their strategic importance and feasibility, avoiding the temptation to bundle every possible concern. Additionally, ensure that all parties understand the rationale behind the linkage, fostering a shared sense of purpose. When executed thoughtfully, linkage transforms political negotiations from adversarial contests into collaborative problem-solving endeavors.

Dance as Resistance: Exploring the Political Power of Movement

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Examples in Diplomacy: Trade deals tied to human rights or environmental policies in international relations

In the realm of international diplomacy, trade deals often serve as a lever to advance broader political agendas, particularly in the areas of human rights and environmental protection. One notable example is the inclusion of labor standards in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced NAFTA. Under this agreement, Mexico committed to labor reforms aimed at protecting workers' rights, including the freedom to organize and bargain collectively. This linkage between trade and labor standards was a direct response to criticisms that NAFTA had exacerbated labor exploitation in Mexico. By conditioning preferential trade access on these reforms, the USMCA illustrates how economic incentives can be used to promote social justice across borders.

Consider the European Union’s approach to trade agreements, which systematically incorporates environmental provisions. The EU-Mercosur trade deal, for instance, includes a commitment to uphold the Paris Climate Agreement. This linkage ensures that economic liberalization does not come at the expense of environmental degradation. However, such agreements are not without challenges. Critics argue that enforcement mechanisms remain weak, raising questions about the effectiveness of these linkages in practice. For diplomats and policymakers, the lesson is clear: crafting robust enforcement frameworks is as critical as the provisions themselves.

A persuasive case can be made for the strategic use of trade linkages in addressing global human rights abuses. The Magnitsky Act in the United States, while not a trade deal per se, demonstrates how economic sanctions can be tied to human rights violations. This model has inspired similar legislation in Canada and the EU, creating a transnational framework for accountability. When trade deals explicitly link market access to human rights benchmarks, they send a powerful signal: economic prosperity is contingent on ethical governance. This approach not only pressures states to reform but also aligns corporate interests with global norms, fostering a more responsible international order.

Comparing the EU’s and China’s approaches to trade linkages reveals contrasting priorities. While the EU emphasizes sustainability and human rights, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) often prioritizes infrastructure development with limited environmental or labor safeguards. This divergence highlights the ideological underpinnings of political linkages in trade. For developing nations, the choice between these models carries significant implications. Aligning with the EU may offer long-term sustainability benefits but could impose stricter regulatory burdens, whereas BRI partnerships may provide immediate economic gains at the risk of environmental and social costs. Navigating these trade-offs requires a nuanced understanding of both the opportunities and pitfalls of such linkages.

Finally, a descriptive analysis of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers insight into regional approaches to political linkages. AfCFTA includes provisions for environmental cooperation and gender equality, reflecting Africa’s unique developmental challenges. By embedding these priorities within a trade framework, African nations aim to ensure that economic integration contributes to broader societal goals. This example underscores the adaptability of political linkages, demonstrating how they can be tailored to address region-specific issues. For practitioners, AfCFTA serves as a model for designing trade agreements that are both economically viable and socially transformative.

Understanding Interest Group Politics: Power, Influence, and Policy Shaping

You may want to see also

Challenges of Linkage: Complexity, potential for deadlock, and balancing competing interests in negotiations

Political linkage, the strategic interconnection of issues in negotiations, often amplifies complexity. Consider a trade agreement where environmental standards are tied to tariff reductions. Each issue carries its own technicalities, stakeholders, and historical baggage. When linked, these issues create a multidimensional puzzle where resolving one aspect inadvertently affects others. For instance, a concession on tariffs might necessitate stricter environmental regulations, which could alienate domestic industries. This compounding complexity demands negotiators to possess not only deep expertise in each domain but also the ability to foresee cascading consequences—a tall order even for seasoned diplomats.

The potential for deadlock looms large in linked negotiations. Take the case of arms control talks where nuclear disarmament is tied to cybersecurity agreements. If one party perceives an imbalance—say, insufficient cybersecurity commitments—progress halts. Unlike standalone issues, where compromises can be isolated, linkage creates a single point of failure. A breakdown in one area stalls the entire process, as parties refuse to move forward without resolution. This interdependence can paralyze negotiations, particularly when issues are emotionally charged or tied to national identity, leaving both sides entrenched in their positions.

Balancing competing interests in linked negotiations requires a delicate calculus. Imagine a climate summit where developed nations link financial aid to emissions cuts from developing countries. While equitable on paper, this linkage pits economic survival against environmental responsibility. Negotiators must weigh short-term gains against long-term sustainability, often under intense domestic and international scrutiny. Practical tips include prioritizing issues based on urgency, using side agreements to address specific concerns, and employing third-party mediators to bridge gaps. For instance, a phased approach—where financial aid is disbursed incrementally as emissions targets are met—can ease tensions and build trust.

To navigate these challenges, negotiators should adopt a structured yet flexible approach. Start by mapping the linkages to identify potential flashpoints. For example, in a labor rights negotiation tied to market access, outline how concessions on wages might impact trade volumes. Next, establish clear thresholds for acceptable outcomes, ensuring they align with core interests. Caution against over-linking; too many interconnected issues can overwhelm the process. Finally, embrace creative solutions like decoupling non-critical issues or introducing time-bound agreements. By acknowledging the inherent risks and preparing accordingly, negotiators can transform linkage from a liability into a lever for comprehensive, durable agreements.

Are Any Kennedys Still Shaping American Politics Today?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political linkage refers to the connection or relationship established between two or more political issues, policies, or actors, often to achieve a specific goal or outcome.

In international relations, political linkage involves tying progress on one issue to cooperation or concessions on another, often used as a bargaining tool between nations to secure agreements or influence behavior.

Examples include bundling unrelated policies into a single legislative package to gain broader support or linking a politician’s stance on one issue to their credibility on another to sway public opinion.

Risks include creating unintended consequences, alienating stakeholders, or complicating negotiations if the linked issues are too divergent or controversial. It can also lead to mistrust if seen as manipulative.