A political eunuch refers to an individual who holds a position of power or influence within a government or political system but is effectively neutered in their ability to exert meaningful authority or effect change. This term metaphorically likens such individuals to historical eunuchs, who were often castrated to serve in royal courts without posing a threat to the ruling dynasty. In the political context, these figures may be constrained by external forces, such as powerful factions, bureaucratic inertia, or authoritarian regimes, rendering them ceremonial or symbolic rather than impactful. Political eunuchs often lack autonomy, decision-making power, or the ability to challenge the status quo, despite their formal titles or roles, highlighting the disconnect between appearance and reality in political structures.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political eunuch refers to a politician or official who is perceived as powerless, ineffective, or lacking real authority, often due to being controlled or constrained by higher powers, factions, or systemic limitations. |

| Origin of Term | Derived from historical eunuchs (castrated males) who held court positions but lacked personal power, symbolizing a figure with influence but no real authority. |

| Key Traits |

|

| Examples |

|

| Modern Context | Increasingly used to describe leaders or officials in democratic systems who are constrained by bureaucracy, party politics, or external influences, rendering them ineffective. |

| Psychological Impact | Often leads to frustration, disillusionment, or a sense of futility among the individual and their supporters. |

| Historical Parallels | Similar to court eunuchs in ancient China or the Ottoman Empire, who held high positions but were ultimately controlled by the ruling elite. |

| Criticism | The term is often used pejoratively to undermine or dismiss the legitimacy of a leader or official, regardless of their actual capabilities. |

| Relevance Today | Highlights the tension between symbolic leadership and actual governance, especially in systems where power is centralized or fragmented. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Ancient practices of castration for court service in various civilizations

- Political Roles: Trusted advisors, administrators, or guardians due to perceived impartiality

- Cultural Significance: Symbolism of power, loyalty, and sacrifice in different societies

- Modern Interpretations: Metaphorical use in politics for neutered influence or compliance

- Ethical Debates: Moral and human rights implications of historical and metaphorical eunuchs

Historical Origins: Ancient practices of castration for court service in various civilizations

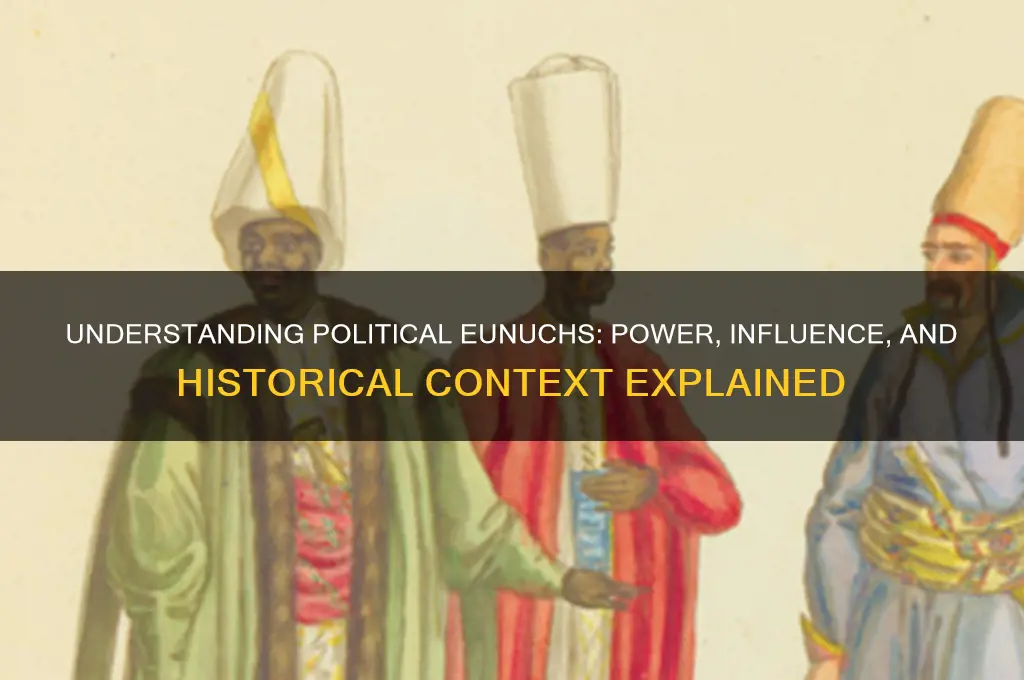

The practice of castration for court service, though seemingly extreme by modern standards, was a widespread and enduring phenomenon across ancient civilizations. From the courts of China to the palaces of the Ottoman Empire, eunuchs—men who had been castrated before puberty—held positions of power and influence, often serving as trusted advisors, administrators, and guardians of royal harems. This section delves into the historical origins of this practice, exploring the motivations, methods, and cultural contexts that shaped the role of eunuchs in various societies.

The Chinese Model: A System of Control and Loyalty

In ancient China, castration for court service dates back to the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), but it reached its zenith during the Han and Tang Dynasties. Eunuchs were prized for their perceived loyalty, as their inability to father children eliminated concerns of dynastic rivalry. The process of castration was often performed by skilled physicians using a procedure known as "biaqing," which involved the removal of the testes while preserving the penis. This method minimized the risk of infection and allowed eunuchs to maintain a degree of physical functionality. By the Ming Dynasty, eunuchs like Zheng He, a renowned admiral, exemplified their potential to wield significant political and military power. However, their influence was not without controversy, as they were frequently accused of corruption and abuse of power, leading to periodic purges and restrictions.

The Ottoman Empire: Guardians of the Harem and Beyond

In the Ottoman Empire, eunuchs were integral to the functioning of the royal court, particularly as guardians of the imperial harem. African boys, often procured through slave markets, were castrated in a process overseen by experienced practitioners. The operation typically involved the removal of both testes and the penis, a more severe method than that practiced in China. These eunuchs, known as "black eunuchs," were highly trusted due to their inability to pose a sexual threat to the sultan’s wives and concubines. Beyond the harem, they served as administrators, diplomats, and even grand viziers, wielding considerable influence over state affairs. The most famous example is Kizlar Agha, the chief black eunuch, who held a position equivalent to a modern-day chief of staff.

Comparative Analysis: Cultural Rationales and Methods

While both China and the Ottoman Empire employed eunuchs for court service, the rationales and methods differed significantly. In China, the focus was on ensuring loyalty and eliminating dynastic threats, whereas in the Ottoman Empire, the primary concern was safeguarding the harem’s sanctity. Chinese castration methods were less severe, reflecting a pragmatic approach to preserving the eunuch’s physical capabilities. In contrast, Ottoman practices were more drastic, emphasizing absolute control and security. These differences highlight how cultural priorities shaped the institution of eunuchdom, adapting it to the unique needs of each civilization.

Practical Considerations and Legacy

Castration for court service was not without risks. The procedure carried a high mortality rate, estimated at 30–50%, due to infection, bleeding, and shock. Survivors often faced social stigma and physical challenges, including hormonal imbalances and psychological trauma. Despite these drawbacks, the practice persisted for centuries, underscoring its perceived value to ruling elites. Today, the legacy of eunuchs offers a fascinating lens through which to study power dynamics, gender roles, and the intersection of medicine and politics in ancient societies. Their stories remind us of the lengths to which humans have gone to secure trust, control, and authority in the corridors of power.

Is 'Gentle Reminder' Polite or Passive-Aggressive? Let's Discuss

You may want to see also

Political Roles: Trusted advisors, administrators, or guardians due to perceived impartiality

Eunuchs, historically known for their physical alteration, often occupied unique political roles due to a perceived impartiality stemming from their inability to produce heirs. This biological reality positioned them as trusted advisors, administrators, and guardians, free from the dynastic ambitions that often clouded the judgment of other courtiers. In imperial China, for instance, eunuchs like Wei Zhongxian and Li Lianying wielded significant influence, managing court affairs and even shaping policy, as their lack of direct lineage made them seemingly above factional strife.

Consider the role of eunuchs in the Ottoman Empire, where they were systematically recruited from Christian territories and trained to serve in the sultan’s court. Their isolation from familial ties and inability to establish their own dynasties made them ideal candidates for administrative roles. The *kapı ağası* (chief eunuch) often acted as a guardian of the harem and a mediator between the sultan and the outside world, ensuring loyalty and discretion. This system highlights how perceived impartiality, born of physical circumstance, translated into political trust and authority.

However, the impartiality of eunuchs was not absolute. While their lack of heirs reduced direct competition for power, they were still human actors with personal ambitions and vulnerabilities. In Ming China, eunuchs like Zheng He, despite their castrated status, pursued influence through patronage networks and military campaigns. This underscores that while eunuchs were often trusted due to their perceived detachment, their actions were still shaped by individual motives and the political contexts in which they operated.

To understand the modern relevance of this dynamic, examine contemporary political systems where individuals without direct familial or dynastic ties are appointed to sensitive roles. For example, technocrats or career bureaucrats are often chosen for their expertise and perceived neutrality, mirroring the historical role of eunuchs. Yet, like their predecessors, these individuals are not immune to bias or self-interest. The lesson here is clear: perceived impartiality is a powerful tool in politics, but it must be balanced with accountability and transparency to prevent abuse of power.

In practical terms, organizations or governments seeking to appoint trusted advisors or administrators should prioritize candidates whose personal stakes are minimized, whether through structural design or ethical frameworks. For instance, term limits or conflict-of-interest policies can mimic the historical "impartiality" of eunuchs without resorting to extreme measures. By focusing on systemic safeguards rather than personal characteristics, modern political systems can harness the benefits of perceived neutrality while avoiding its pitfalls.

Assessing Bloomberg Politics: Reliability, Bias, and Accuracy in Reporting

You may want to see also

Cultural Significance: Symbolism of power, loyalty, and sacrifice in different societies

The concept of the political eunuch, historically rooted in physical alteration for court service, transcends its literal definition to embody profound cultural symbolism. In societies from ancient China to the Ottoman Empire, eunuchs were not merely servants but symbols of absolute loyalty and sacrifice. Their physical state, often seen as a renunciation of personal desires, made them ideal guardians of power, trusted with secrets and the inner workings of empires. This duality—power through self-denial—highlights how cultures valorize sacrifice as a pathway to influence and trust.

Consider the Ming Dynasty, where eunuchs like Zheng He wielded immense authority, leading naval expeditions and shaping foreign policy. Their rise was not despite their castration but because of it; their inability to produce heirs neutralized threats to the ruling class, making them both powerful and expendable. This paradoxical status underscores how sacrifice, when culturally codified, can elevate individuals to roles of unprecedented influence. In contrast, the Ottoman Empire’s *Inner Service* system institutionalized eunuchs as protectors of the harem and advisors to the sultan, embedding their symbolic purity and loyalty into the fabric of governance.

Analyzing these examples reveals a recurring theme: eunuchs served as living metaphors for the idealized relationship between power and submission. Their bodies, marked by sacrifice, became vessels for cultural narratives about duty and fidelity. In China, eunuchs were often depicted in art and literature as both guardians and victims, their stories cautioning against the corrupting influence of power while celebrating their unwavering service. In Africa’s kingdoms, such as Kongo, eunuchs were emissaries of trust, their altered state symbolizing a commitment to diplomatic neutrality.

To understand the modern resonance of this symbolism, examine how contemporary politics and corporate structures replicate the eunuch’s role. Advisors, bureaucrats, and executives often adopt a form of symbolic castration, prioritizing organizational loyalty over personal ambition. This dynamic is particularly evident in authoritarian regimes, where proximity to power demands visible sacrifices—whether familial, ethical, or ideological. The takeaway is clear: the eunuch’s cultural significance endures as a blueprint for how societies define and reward loyalty, often at the cost of individual autonomy.

Practically, this symbolism offers a lens for navigating power structures. For instance, in organizational settings, demonstrating commitment through visible sacrifices (e.g., long hours, public alignment with leadership) can signal loyalty, though it risks exploitation. To mitigate this, set boundaries that preserve personal integrity while fulfilling professional duties. Historically, some eunuchs, like the Ottoman *Kızlar Ağası*, amassed power by leveraging their symbolic role, proving that even within restrictive frameworks, agency can be reclaimed. This duality—sacrifice as both tool and trap—remains a timeless lesson in the interplay of power and loyalty.

Understanding Political Referendums: Direct Democracy in Action Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$30 $23.99

Modern Interpretations: Metaphorical use in politics for neutered influence or compliance

The term "political eunuch" has evolved beyond its historical roots, now serving as a metaphor for individuals or entities whose political influence has been systematically neutered. In modern politics, this metaphor is often applied to figures who, despite holding positions of nominal power, are rendered ineffective by external constraints, whether imposed by superiors, systemic structures, or self-censorship. Such individuals are seen as compliant tools, stripped of their ability to challenge the status quo or enact meaningful change.

Consider the role of a cabinet member in an authoritarian regime. While they may hold a prestigious title, their decisions are often dictated by the ruling authority, leaving them little room for independent action. This dynamic transforms them into a political eunuch, their influence castrated by the need to conform to the regime’s agenda. Similarly, in democratic systems, bureaucrats or appointed officials may face similar pressures, particularly when their tenure depends on aligning with the executive branch’s priorities rather than pursuing their own vision.

To identify a political eunuch, look for patterns of compliance without conviction. These individuals often parrot the party line, avoid controversial topics, and prioritize self-preservation over policy innovation. For instance, a legislator who consistently votes along party lines, even when it contradicts their earlier stances, may be acting as a political eunuch. Their ability to influence policy is neutered by the need to maintain favor within their party or avoid retribution.

Avoiding the fate of a political eunuch requires strategic assertiveness. For those in positions of potential influence, it’s crucial to cultivate a base of independent support, whether through grassroots movements, media presence, or cross-party alliances. This provides a buffer against undue pressure and allows for greater autonomy. Additionally, framing policy proposals in ways that align with broader institutional goals can create the appearance of compliance while advancing personal or public interests.

Ultimately, the metaphor of the political eunuch highlights the tension between power and autonomy in modern governance. It serves as a cautionary tale for those who aspire to influence policy, reminding them that true authority lies not in titles but in the ability to act independently. By recognizing the signs of neutered influence and taking proactive steps to safeguard autonomy, individuals can avoid becoming mere instruments of others’ agendas.

Do Political Sanctions Achieve Goals or Escalate Global Tensions?

You may want to see also

Ethical Debates: Moral and human rights implications of historical and metaphorical eunuchs

The concept of a political eunuch, whether historical or metaphorical, raises profound ethical questions about autonomy, identity, and human rights. Historically, eunuchs were individuals who underwent castration, often involuntarily, to serve in specific roles within royal courts or religious institutions. This practice, while rooted in cultural and political necessity, was a stark violation of bodily integrity and personal freedom. Today, the term is metaphorically applied to individuals who are politically neutered, stripped of their agency or influence to serve a larger power structure. Both interpretations demand scrutiny through the lens of morality and human rights.

Consider the historical eunuch: a figure often revered for their loyalty yet denied the fundamental right to self-determination. Castration, typically performed before puberty, not only altered their physicality but also their social standing, relegating them to roles that society deemed "safe" or "pure." Ethically, this practice exemplifies the commodification of human beings, where the body becomes a tool for political or religious ends. The moral dilemma lies in balancing cultural norms against universal human rights. For instance, Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights prohibits torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment—a standard that historical eunuch practices would unequivocally fail. Advocates for cultural relativism might argue that such practices were contextually acceptable, but this perspective risks normalizing violations of basic human dignity.

Metaphorical eunuchs, on the other hand, face a different but equally troubling ethical landscape. In modern politics, the term often describes individuals or groups whose voices are silenced, opinions suppressed, or influence neutered to maintain the status quo. This could range from whistleblowers facing retaliation to marginalized communities excluded from decision-making processes. The moral implication here is the erosion of democratic principles and the right to participate in public life. Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees the right to take part in the government of one’s country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. When political systems systematically disenfranchise certain voices, they undermine this right, creating a moral crisis of representation and equality.

A comparative analysis reveals that both historical and metaphorical eunuchs suffer from the denial of agency, albeit in different forms. While the former endured physical mutilation, the latter face psychological and structural oppression. The takeaway is that both scenarios highlight the fragility of human rights in the face of power. To address these ethical dilemmas, societies must prioritize the protection of bodily autonomy and political participation. Practical steps include enacting laws that safeguard against forced medical procedures and ensuring transparent, inclusive governance structures. For instance, age-appropriate education on human rights can empower younger generations to recognize and resist systemic oppression.

Ultimately, the ethical debates surrounding eunuchs—historical and metaphorical—serve as a mirror to society’s values. They challenge us to reconcile cultural practices and political systems with the universal principles of dignity and freedom. By examining these cases, we not only confront the past but also chart a course for a more just future. The question remains: will we allow power to dictate humanity, or will we uphold the rights that define it?

Understanding the Political Juggernaut: Power, Influence, and Unstoppable Momentum

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political eunuch refers to a person in a position of power or influence who lacks the ability or willingness to exercise meaningful authority, often due to being controlled or constrained by others.

Someone becomes a political eunuch when their decision-making power is severely limited by external forces, such as a dominant leader, party, or system, rendering them effectively powerless despite their formal role.

Not necessarily. Some political eunuchs may be aware of their limited power, while others may operate under the illusion of authority, unaware that their decisions are heavily influenced or dictated by others.

Yes, a political eunuch can regain power by asserting independence, building alliances, or changing the circumstances that restrict their authority, though this often requires significant effort and strategic maneuvering.