A political characteristic refers to a defining feature or trait that shapes the behavior, structure, or ideology of political systems, actors, or processes. These characteristics can include elements such as power distribution, governance mechanisms, citizen participation, and the role of institutions. They often reflect the values, norms, and principles that underpin a society's approach to decision-making, conflict resolution, and resource allocation. Understanding political characteristics is essential for analyzing how governments function, how policies are formulated, and how individuals and groups interact within the political sphere. Examples of political characteristics include democracy, authoritarianism, federalism, and the rule of law, each of which influences the dynamics of political systems in distinct ways.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Power Dynamics: Study of authority distribution, influence, and control within political systems and structures

- Ideology & Beliefs: Examination of political philosophies, values, and principles shaping policies and governance

- Institutions & Roles: Analysis of formal organizations (e.g., governments, parties) and their functions

- Conflict & Cooperation: Exploration of political interactions, negotiations, and alliances between actors or groups

- Participation & Citizenship: Understanding civic engagement, voting, activism, and rights in political processes

Power Dynamics: Study of authority distribution, influence, and control within political systems and structures

Power dynamics are the invisible currents that shape political systems, determining who holds authority, wields influence, and exercises control. At its core, this study examines how power is distributed—whether concentrated in the hands of a few or dispersed among many—and the mechanisms through which it is maintained or challenged. Consider the contrast between a democratic system, where power is theoretically shared through voting and representation, and an autocracy, where it is centralized in a single leader or elite group. These structures are not static; they evolve through negotiation, coercion, or revolution, reflecting the fluid nature of human relationships and interests.

To analyze power dynamics effectively, begin by mapping the key players within a political system. Identify formal authority figures—such as elected officials or monarchs—and informal influencers, like lobbyists, media outlets, or grassroots movements. For instance, in the United States, while Congress holds legislative power, corporate lobbying often shapes policy outcomes, demonstrating how influence can bypass formal channels. Next, examine the tools of control: laws, economic resources, military force, or ideological narratives. A practical tip for researchers is to trace funding flows or track legislative changes over time to uncover hidden power networks.

A persuasive argument for studying power dynamics lies in its ability to expose inequities and predict systemic vulnerabilities. For example, in systems where power is heavily concentrated, marginalized groups often lack representation, leading to policies that perpetuate inequality. Conversely, overly decentralized systems may struggle with decision-making efficiency, as seen in coalition governments plagued by gridlock. By understanding these patterns, policymakers and activists can design interventions—such as electoral reforms or transparency initiatives—to balance power more equitably.

Comparatively, power dynamics in traditional versus modern political systems reveal fascinating contrasts. In feudal societies, power was often tied to land ownership and hereditary titles, creating rigid hierarchies. Today, in the digital age, power can be wielded through data control and algorithmic influence, as seen with tech giants shaping public discourse. This shift underscores the need for adaptive frameworks that account for evolving sources of authority. A cautionary note: while technology democratizes access to information, it also risks centralizing power in the hands of those who control the platforms.

In conclusion, the study of power dynamics is both a diagnostic tool and a roadmap for change. It requires a multidisciplinary approach—combining political science, sociology, and economics—to capture the complexity of authority distribution. For practitioners, start by asking: Who benefits from the current power structure? Whose voices are excluded? By systematically addressing these questions, individuals and institutions can work toward systems that distribute power more justly, fostering stability and inclusivity in the process.

Understanding Pakora Politics: India's Street Food Metaphor for Employment Debate

You may want to see also

Ideology & Beliefs: Examination of political philosophies, values, and principles shaping policies and governance

Political ideologies are the bedrock of governance, shaping how societies organize power, distribute resources, and resolve conflicts. Consider liberalism, which champions individual freedoms, free markets, and limited government intervention. Its core belief in human rationality and progress has driven policies like deregulation, tax cuts, and civil rights expansions. Yet, critics argue its emphasis on competition can exacerbate inequality, revealing how ideology’s strengths often mirror its flaws.

To examine political philosophies effectively, start by identifying their foundational values. For instance, socialism prioritizes collective welfare over individual gain, advocating for public ownership of key industries and wealth redistribution. This principle manifests in policies like universal healthcare or progressive taxation. However, implementation varies: Nordic countries blend socialist principles with market economies, while historical examples like the Soviet Union pursued state control, highlighting the spectrum within a single ideology.

When dissecting these systems, ask: *How do beliefs translate into actionable governance?* Take conservatism, which values tradition, hierarchy, and gradual change. Its policies often reflect a desire to preserve social order, such as supporting established institutions or opposing rapid reforms. Yet, conservatism’s definition of "tradition" can shift—what was once radical (e.g., women’s suffrage) becomes part of its defense of stability, illustrating ideology’s dynamic nature.

A practical tip for understanding ideological impact: trace policy outcomes to their philosophical roots. For example, environmental policies differ sharply between ideologies. Green politics, rooted in ecological sustainability, pushes for renewable energy mandates and carbon taxes. In contrast, libertarianism might oppose such regulations, favoring market-driven solutions. This comparison reveals how beliefs dictate not just goals but methods, offering a lens to predict policy directions.

Finally, recognize that ideologies are not static; they evolve in response to societal pressures. Feminism, initially focused on legal equality, now encompasses intersectional issues like economic justice and LGBTQ+ rights. This evolution shows how ideologies adapt while retaining core principles, making them both enduring and malleable. By studying these shifts, one can better anticipate how political philosophies will shape future governance.

Understanding Political Caucuses: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Role and Function

You may want to see also

Institutions & Roles: Analysis of formal organizations (e.g., governments, parties) and their functions

Formal organizations, such as governments and political parties, are the backbone of any political system, serving as the structural framework through which power is exercised and decisions are made. These institutions are not merely bureaucratic entities but are designed to fulfill specific roles that ensure stability, representation, and governance. Governments, for instance, are tasked with creating and enforcing laws, managing public resources, and providing essential services like education and healthcare. Political parties, on the other hand, act as intermediaries between the public and the state, aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and competing for power. Together, these organizations form a complex web of interactions that shape political outcomes.

Consider the function of a legislature within a government. Its primary role is to draft, debate, and pass laws that reflect the collective will of the people. However, this process is not as straightforward as it seems. Legislatures must balance competing interests, navigate partisan divides, and ensure transparency. For example, in the United States Congress, the committee system plays a critical role in scrutinizing bills before they reach the floor for a vote. This layered process highlights how formal institutions are designed to prevent hasty decision-making and foster deliberation. Without such structures, governance would risk becoming arbitrary or dominated by narrow interests.

Political parties, while often criticized for their divisiveness, are essential for democratic functioning. They simplify the political landscape for voters by offering distinct platforms and ideologies. For instance, in multiparty systems like Germany’s, parties like the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) provide clear alternatives, allowing citizens to align with their values. Parties also serve as talent pipelines, grooming leaders and preparing them for governance roles. However, their effectiveness depends on internal democracy and accountability. A party that suppresses dissent or prioritizes loyalty over competence undermines its own role as a healthy political institution.

The interplay between institutions and roles becomes particularly evident during crises. Governments must act swiftly, often bypassing normal procedures, while still maintaining legitimacy. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries invoked emergency powers to implement lockdowns and allocate resources. This raised questions about the balance between efficiency and oversight. Formal institutions like courts and independent media played a crucial role in holding governments accountable, demonstrating how the functions of these organizations are interdependent. Without checks and balances, even well-intentioned actions can lead to abuses of power.

To analyze formal organizations effectively, one must look beyond their stated functions to their actual performance. Are governments responsive to citizen needs? Do political parties genuinely represent their constituents, or are they captive to special interests? A practical tip for assessing this is to examine key performance indicators, such as voter turnout, legislative productivity, and public trust in institutions. For instance, a government with high voter turnout but low legislative output may indicate a disconnect between electoral participation and policy delivery. By focusing on these metrics, one can gain a nuanced understanding of how institutions fulfill their roles and where reforms may be needed.

Understanding Constructivism: Shaping Political Realities Through Shared Ideas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

Conflict & Cooperation: Exploration of political interactions, negotiations, and alliances between actors or groups

Political interactions are inherently shaped by the dual forces of conflict and cooperation, which often coexist in a delicate balance. Consider the European Union, a prime example of how historically adversarial nations have forged alliances to promote economic and political stability. Yet, even within this cooperative framework, conflicts arise—such as Brexit—highlighting the tension between sovereignty and collective governance. This dynamic illustrates that political actors must navigate competing interests while seeking mutual benefits, a process that requires strategic negotiation and compromise.

To effectively manage conflict and foster cooperation, actors must employ specific strategies. First, identify shared goals that transcend immediate differences. For instance, during climate negotiations, countries with disparate economic priorities often unite under the common threat of global warming. Second, establish clear communication channels to prevent misunderstandings. The Camp David Accords of 1978 succeeded partly because of structured dialogue between Egypt and Israel, mediated by the U.S. Third, incentivize cooperation through reciprocal agreements, such as trade pacts or security alliances. However, beware of zero-sum thinking, which can escalate conflicts by framing gains for one party as losses for another.

A comparative analysis reveals that successful alliances often hinge on power asymmetries and trust-building mechanisms. NATO, for example, thrives on the dominant role of the U.S. in providing security guarantees, while smaller members contribute resources and legitimacy. In contrast, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) relies on consensus-building and non-interference principles to accommodate diverse political systems. Both models demonstrate that cooperation can be sustained through either hierarchical stability or egalitarian norms, depending on the context.

Descriptively, political negotiations resemble a high-stakes chess game, where each move is calculated to advance one’s position while anticipating the opponent’s response. Take the Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA), where years of negotiations culminated in a temporary resolution of a decades-long standoff. The agreement’s success rested on incremental concessions, such as Iran limiting uranium enrichment in exchange for sanctions relief. However, its fragility—evident in the U.S. withdrawal in 2018—underscores the challenges of sustaining cooperation in the face of shifting domestic and international pressures.

In practice, fostering cooperation amidst conflict requires a nuanced understanding of actors’ motivations and constraints. For instance, when negotiating with authoritarian regimes, focus on tangible incentives like economic aid or diplomatic recognition, as ideological appeals often fall flat. Conversely, when dealing with democratic allies, emphasize shared values and public accountability. A useful tip is to frame negotiations as problem-solving exercises rather than battles to be won. By adopting a collaborative mindset, political actors can transform adversarial relationships into partnerships, even if temporary or issue-specific. Ultimately, the art of politics lies in recognizing that conflict and cooperation are not opposites but interdependent facets of human interaction.

Are Dominant Political Entities Truly Equivalent to Sovereign Countries?

You may want to see also

Participation & Citizenship: Understanding civic engagement, voting, activism, and rights in political processes

Civic engagement is the lifeblood of democracy, yet its pulse varies widely across societies. In the United States, for instance, voter turnout in the 2020 presidential election reached 66%, the highest since 1900, while in local elections, participation often drops below 30%. This disparity highlights a critical truth: engagement is not uniform, and its forms—voting, activism, community organizing—reflect both individual agency and systemic barriers. Understanding these dynamics requires examining not just the act of participation but the structural and cultural forces that shape it.

Consider voting, the most formalized act of citizenship. In countries with compulsory voting, like Australia, turnout hovers around 90%, compared to voluntary systems where it fluctuates dramatically. This suggests that while personal motivation matters, institutional design plays a decisive role. For example, early voting and mail-in ballots have been shown to increase participation by 2-5 percentage points in U.S. elections, particularly among younger voters and those with mobility challenges. Yet, such reforms are often contested, revealing how political systems can either empower or suppress civic engagement.

Activism, another cornerstone of participation, operates outside formal structures but is equally vital. The Black Lives Matter movement, for instance, mobilized millions globally, leveraging social media to amplify demands for racial justice. Unlike voting, activism thrives on flexibility and immediacy, often responding to crises or injustices that traditional processes fail to address. However, its impact is uneven: while it can shift public discourse, it rarely translates directly into policy without sustained pressure and strategic alignment with electoral politics.

Rights, the foundation of citizenship, are both a shield and a sword in political processes. In India, the Right to Information Act has empowered citizens to hold government accountable, leading to over 6 million requests annually since its enactment in 2005. Yet, rights are meaningless without enforcement. In many countries, marginalized groups face legal or practical barriers to exercising their rights, from voter ID laws that disproportionately affect minorities to restrictive protest regulations. This underscores the need for vigilance in protecting and expanding civic freedoms.

Ultimately, participation and citizenship are not static concepts but evolving practices shaped by context and struggle. To foster meaningful engagement, societies must address structural inequalities, innovate in democratic institutions, and cultivate a culture of active citizenship. This requires more than individual effort—it demands collective action to ensure that political processes are inclusive, responsive, and truly representative of the people they serve.

Are Political Bosses Corrupt? Examining Power, Influence, and Integrity in Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political characteristic is a defining feature or trait of a political system, ideology, or behavior. It encompasses elements such as governance structures, power distribution, decision-making processes, and the relationship between the state and its citizens.

Political characteristics vary across countries due to differences in history, culture, economic systems, and social values. For example, some nations prioritize individual freedoms (e.g., liberal democracies), while others emphasize collective welfare (e.g., socialist states).

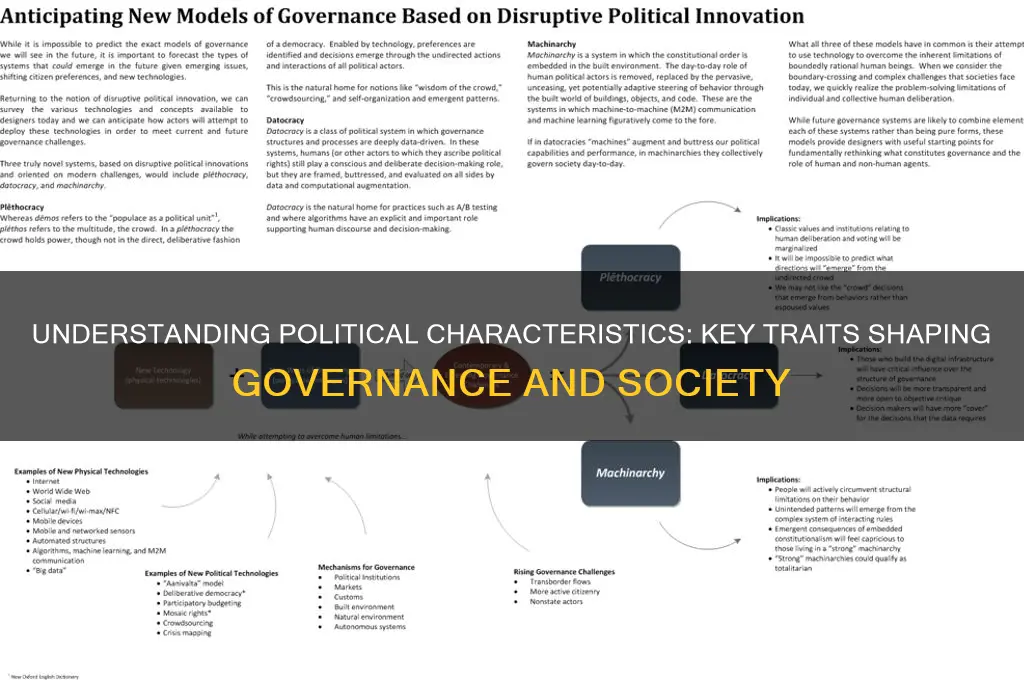

Political characteristics are not static; they can evolve due to factors like societal shifts, technological advancements, or political reforms. Revolutions, elections, and global events often drive changes in a country's political landscape.

Political characteristics influence public policy by determining how decisions are made, who holds power, and what values are prioritized. For instance, a centralized government may implement policies differently than a decentralized one, reflecting its unique political traits.