A political asylee is an individual who has been granted legal protection by a foreign country due to a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country based on their political opinion, race, religion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group. This status is recognized under international law, particularly the 1951 Refugee Convention, and is designed to safeguard those who face threats such as imprisonment, torture, or death if they return to their country of origin. To qualify, applicants must demonstrate that their fear of persecution is both credible and directly linked to one of the protected grounds. Once granted asylum, individuals receive the right to live and work in the host country, access to social services, and protection from deportation, though the specific benefits and obligations may vary by nation. Political asylum serves as a critical humanitarian tool, ensuring that those fleeing oppression can seek safety and rebuild their lives in a secure environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political asylee is an individual granted protection by another country because they have suffered persecution or fear they will suffer persecution due to their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. |

| Legal Basis | Protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. |

| Eligibility Criteria | Must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country. |

| Grounds for Asylum | Race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. |

| Application Process | Must apply for asylum in the country where protection is sought, often through immigration authorities. |

| Documentation Required | Evidence of persecution or fear, such as affidavits, country condition reports, and personal statements. |

| Rights Granted | Legal stay, work authorization, access to education and healthcare, and protection from deportation. |

| Duration of Status | Typically indefinite, but can be reviewed if conditions in the home country change. |

| Family Inclusion | Immediate family members (spouse, children) may also be granted asylum status. |

| Travel Restrictions | May face restrictions on travel to the home country or other specific regions. |

| Path to Citizenship | Many countries allow asylees to apply for permanent residency and eventually citizenship. |

| Global Statistics (2023) | Over 3 million recognized asylum seekers worldwide (UNHCR data). |

| Key Countries of Asylum | United States, Germany, France, Canada, and Sweden are among the top recipients. |

| Challenges Faced | Integration difficulties, language barriers, and potential discrimination. |

| International Protection | Protected under international law, with UNHCR overseeing global refugee affairs. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Legal Definition: A person granted protection in another country due to persecution fears in their homeland

- Eligibility Criteria: Must prove well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, politics, or identity

- Application Process: File Form I-589 with USCIS, attend interviews, and provide evidence supporting asylum claims

- Rights & Benefits: Access work permits, social services, and pathways to permanent residency and citizenship

- Challenges Faced: Long processing times, legal complexities, and potential detention during application review

Legal Definition: A person granted protection in another country due to persecution fears in their homeland

A political asylee is legally defined as an individual who has been granted protection in a foreign country due to well-founded fears of persecution in their home nation. This status is not automatically conferred but requires a rigorous application process, often involving interviews, evidence submission, and legal representation. The persecution must be based on one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. For instance, a journalist fleeing a regime that targets critics of the government would likely qualify, as their fear of persecution is directly tied to their political opinion.

The legal framework for asylum is rooted in international law, particularly the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. In the United States, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) outlines the criteria for asylum, emphasizing that the applicant must demonstrate a credible fear of persecution. This is not merely a subjective claim but requires objective evidence, such as documentation of threats, violence, or systemic discrimination. For example, a member of an ethnic minority facing state-sponsored violence would need to provide reports from human rights organizations or news articles corroborating their claims.

Granting asylum is a humanitarian act but also a legal obligation for signatory countries. Once asylum is granted, the individual receives certain rights, including the ability to live and work in the host country, access to healthcare, and protection from deportation. However, this status is not permanent; it can be revoked if conditions in the home country improve or if the asylee commits certain crimes. For instance, if a democratic government replaces a repressive regime, the asylee may be required to reevaluate their claim.

Practical considerations for asylees include understanding the limitations of their status. While asylum provides protection, it does not automatically grant citizenship or permanent residency. Asylees must apply for these separately, often after a waiting period. Additionally, they should be aware of the importance of maintaining their legal status by complying with reporting requirements and keeping their contact information updated with immigration authorities. Failure to do so can jeopardize their asylum status and lead to legal complications.

In summary, the legal definition of a political asylee hinges on the intersection of fear, persecution, and protected grounds. It is a status granted through a meticulous process, offering protection and rights but also requiring ongoing compliance. For those fleeing persecution, understanding this definition and its implications is crucial for navigating the complexities of seeking safety in a foreign land.

Suffragists as Political Prisoners: Unraveling the Fight for Women's Rights

You may want to see also

Eligibility Criteria: Must prove well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, politics, or identity

To qualify as a political asylee, one must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country, specifically tied to one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. This criterion is not merely a formality but a rigorous standard designed to distinguish genuine refugees from economic migrants or those fleeing generalized violence. The burden of proof lies with the applicant, who must provide credible evidence that their fear is both subjective (they personally hold the fear) and objective (a reasonable person in their circumstances would also fear persecution).

Consider the case of a journalist from a country where the government systematically targets critics. If this individual can show that their reporting has led to threats, harassment, or violence, they may meet the eligibility criteria. The key is to establish a clear nexus between the persecution and one of the protected grounds. For instance, if the journalist’s articles criticize government corruption, their fear of persecution is based on political opinion. Documentation such as threatening letters, police reports, or affidavits from witnesses can strengthen their claim. Without such evidence, even a compelling narrative may fall short.

Proving a well-founded fear is not about predicting the future with certainty but demonstrating a reasonable possibility of persecution. For example, a member of an ethnic minority fleeing a country with a history of targeted violence against their group would need to show that their race or nationality places them at risk. This could involve presenting country condition reports, news articles, or expert testimony detailing the ongoing persecution. Asylum officers and judges scrutinize these claims to ensure they are not based on speculative or exaggerated fears. Practical tip: Applicants should focus on specific incidents and patterns of harm rather than general statements about their country’s instability.

A common misconception is that persecution must be carried out by the government. In reality, it can also be inflicted by non-state actors, such as extremist groups or gangs, if the government is unwilling or unable to control them. For instance, a religious minority facing attacks from a militant group could qualify for asylum if the government fails to provide protection. This distinction is crucial, as many applicants mistakenly assume they must prove direct government involvement. Caution: Claims based on non-state actors require additional evidence of the government’s inability or unwillingness to intervene.

Finally, the concept of “particular social group” is often the most complex of the five grounds. It encompasses identities such as gender, sexual orientation, or familial relationships, but the group must be defined by characteristics that are immutable or so fundamental that members should not be required to change them. For example, a woman fleeing female genital mutilation in a country where the practice is widespread and the government does not intervene could qualify under this category. Takeaway: Eligibility hinges on the applicant’s ability to link their fear of persecution to one of these protected grounds, supported by concrete evidence and a clear understanding of legal standards.

Faith and Governance: A Christian's Guide to Navigating Political Engagement

You may want to see also

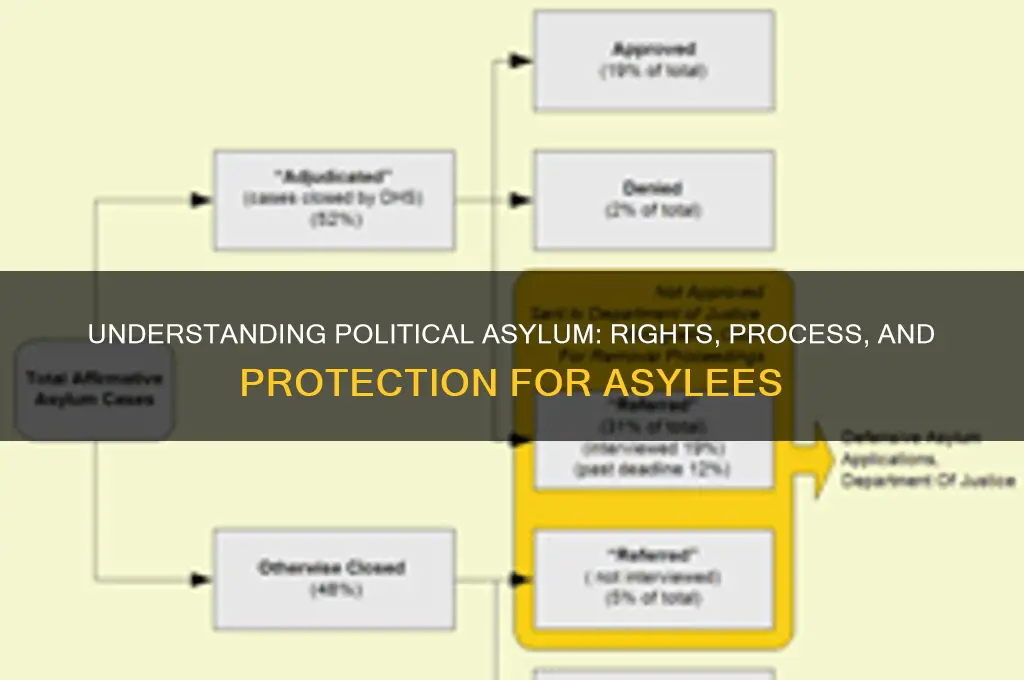

Application Process: File Form I-589 with USCIS, attend interviews, and provide evidence supporting asylum claims

To become a political asylee in the United States, one must navigate a rigorous application process that demands precision, patience, and compelling evidence. The journey begins with filing Form I-589, Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal, with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). This form is the cornerstone of your asylum claim, requiring detailed information about your identity, background, and the persecution you fear if returned to your home country. It’s not just a bureaucratic exercise; it’s a narrative of survival and a plea for protection. USCIS mandates that this form be filed within one year of your arrival in the U.S., unless you can prove extraordinary circumstances for a late submission. Missing this deadline can jeopardize your entire case, underscoring the need for prompt action and legal guidance.

Once Form I-589 is submitted, the waiting game begins, often punctuated by an asylum interview. This is no ordinary appointment; it’s a high-stakes conversation where an asylum officer scrutinizes your story, assesses your credibility, and evaluates the evidence you’ve provided. Preparation is key. Bring originals and copies of all supporting documents, such as police reports, medical records, affidavits from witnesses, or news articles corroborating your claims. Dress professionally, arrive early, and practice answering questions about your persecution clearly and consistently. Remember, the officer is not just looking for facts but also for the authenticity of your fear. A single inconsistency can cast doubt on your entire case, so honesty and clarity are paramount.

The evidence you provide is the backbone of your asylum claim, and its quality can make or break your case. Country condition reports from the U.S. Department of State, human rights organizations, or news outlets can contextualize the persecution you’ve faced. Personal documents, such as photographs of injuries or threatening letters, add a tangible layer to your narrative. If you’ve been politically active, include proof of your involvement, such as membership cards or event photographs. For those fleeing religious or social group persecution, affidavits from religious leaders or community members can bolster your claim. The goal is to create an irrefutable case that your fear of persecution is well-founded and directly tied to a protected ground: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

Throughout this process, be mindful of potential pitfalls. Incomplete forms or missing evidence can lead to delays or denials. If English isn’t your first language, bring a certified translator to ensure nothing is lost in translation. If you’re detained, the process accelerates, and you’ll face an immigration judge instead of a USCIS officer, adding another layer of complexity. Legal representation, while not mandatory, is highly recommended. An experienced immigration attorney can help you navigate the intricacies of the process, from drafting a compelling I-589 to preparing for the interview. They can also assist with waivers if you’ve missed the one-year filing deadline or have other complicating factors.

In conclusion, the path to becoming a political asylee is fraught with challenges but not insurmountable. Filing Form I-589, acing the asylum interview, and providing irrefutable evidence are the pillars of a successful application. Each step requires meticulous attention to detail, strategic planning, and, often, emotional resilience. While the process may seem daunting, it’s a lifeline for those fleeing persecution, offering a chance to rebuild in safety. Approach it with determination, seek support when needed, and remember: your story matters, and the evidence you present can be the key to a new beginning.

Apple's Political Influence: Corporate Power or Neutrality in Global Affairs?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rights & Benefits: Access work permits, social services, and pathways to permanent residency and citizenship

Political asylees, recognized for fleeing persecution in their home countries, gain access to critical rights and benefits in their host nation. One of the most immediate advantages is the ability to obtain a work permit, typically within 150 days of filing an asylum application in the United States, for example. This permit allows asylees to legally enter the workforce, providing financial stability and independence. However, the process requires submitting Form I-765, Application for Employment Authorization, along with supporting documents, and understanding that work authorization is not automatic upon filing for asylum.

Beyond employment, asylees are entitled to social services that mirror those available to citizens and permanent residents. This includes access to healthcare through Medicaid, food assistance via SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), and enrollment in refugee cash assistance programs for a limited period, usually up to eight months. Notably, asylees are also eligible for Social Security benefits if they meet work credit requirements. These services are designed to ease integration and ensure basic needs are met while asylees rebuild their lives.

A less immediate but equally transformative benefit is the pathway to permanent residency and citizenship. In the U.S., asylees can apply for a green card after one year of continuous presence in the country. After holding a green card for five years (or three years if married to a U.S. citizen), they can pursue naturalization. This progression from asylee to citizen underscores the host country’s commitment to providing long-term security and belonging to those who have escaped persecution.

However, navigating these benefits requires vigilance. Work permits must be renewed periodically, and eligibility for social services can vary by state. For instance, while Medicaid is federally mandated, states have discretion in implementing SNAP benefits, leading to inconsistencies. Additionally, the path to citizenship demands meticulous documentation of continuous residence and good moral character. Practical tips include maintaining detailed records of employment, residence, and tax filings, as these documents are crucial for green card and citizenship applications.

In comparison to other immigrant categories, asylees often face unique challenges, such as trauma recovery and legal complexities, but their rights and benefits are specifically tailored to address these vulnerabilities. For instance, unlike refugees who are processed overseas, asylees apply for status within the host country, granting them immediate access to work permits and services upon approval. This distinction highlights the host nation’s acknowledgment of the urgent needs of those seeking safety at its borders.

Ultimately, the rights and benefits afforded to political asylees serve as both a lifeline and a bridge. They provide immediate relief through work permits and social services while offering a long-term vision of stability through residency and citizenship. By understanding and leveraging these entitlements, asylees can not only survive but thrive in their new home.

Mastering the Art of Politics: A Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming a Politician

You may want to see also

Challenges Faced: Long processing times, legal complexities, and potential detention during application review

The journey to becoming a political asylee is fraught with obstacles that test resilience and patience. One of the most daunting challenges is the lengthy processing time, which can stretch from months to years. For instance, in the United States, the average asylum case takes 18 to 24 months to resolve, leaving applicants in limbo. During this period, individuals often struggle to secure stable employment, access healthcare, or even open a bank account, as their legal status remains uncertain. This prolonged uncertainty exacerbates emotional and financial strain, making it difficult to rebuild a life in the host country.

Navigating the legal complexities of asylum applications is another significant hurdle. Asylum laws vary widely by country, and the criteria for approval are stringent. Applicants must provide detailed evidence of persecution, often requiring documentation from their home country, which may be impossible to obtain. Legal representation is critical, but affordable or pro bono services are scarce, leaving many to navigate the system alone. For example, in the European Union, only 30% of asylum seekers have legal counsel, increasing the likelihood of procedural errors that can derail their case. Without a clear understanding of legal requirements, even legitimate claims can be denied.

Perhaps the most harrowing challenge is the potential for detention during the application review process. Many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, detain asylum seekers while their cases are pending, often in overcrowded and inhumane conditions. Detention can last for weeks, months, or even years, with limited access to legal resources or mental health support. For vulnerable populations, such as children or survivors of trauma, detention compounds their suffering and can lead to long-term psychological damage. Advocacy groups have documented cases where detention has deterred individuals from pursuing asylum altogether, fearing further harm.

To mitigate these challenges, applicants should take proactive steps. First, document everything: gather evidence of persecution, including medical records, police reports, and witness statements, as early as possible. Second, seek legal assistance immediately, even if it means reaching out to multiple organizations until finding a suitable advocate. Third, prepare for detention by understanding your rights and having a support network in place. Organizations like the UNHCR or local immigrant rights groups can provide resources and guidance. Finally, stay informed about changes in asylum policies, as these can impact processing times and eligibility criteria.

In conclusion, the path to political asylum is riddled with systemic barriers that demand perseverance and strategic action. By addressing long processing times, legal complexities, and the risk of detention head-on, applicants can increase their chances of a successful outcome. While the process is arduous, understanding these challenges and preparing accordingly can make a critical difference in securing safety and a new beginning.

Preventing Political Disharmony: Strategies for Unity and Stability in Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political asylee is an individual who has been granted asylum in another country because they have suffered persecution or have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country due to their political opinion, race, religion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group.

To become a political asylee, an individual must file an application for asylum with the appropriate government authorities in the country where they seek protection. They must provide evidence of past persecution or a credible fear of future persecution based on one of the protected grounds.

Political asylees typically gain the right to live and work legally in the host country, access to healthcare and education, and protection from being returned to their home country where they face persecution. They may also be eligible to apply for permanent residency or citizenship after a certain period.

Returning to the home country could jeopardize an asylee's status, as it may be interpreted as evidence that they no longer fear persecution. However, some asylees may visit their home country under specific circumstances, such as family emergencies, with prior approval from the host country's authorities.