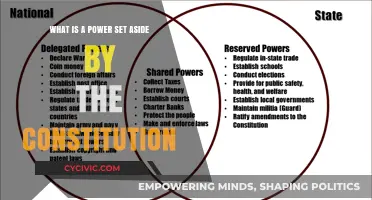

There are several schools of thought on how to interpret the US Constitution, including textualism, originalism, modernism, and democratic interpretation. Textualism, also known as pure textualism or literalism, focuses on the plain meaning of the text of a legal document. Textualists believe there is an objective meaning to the text and do not typically inquire into the intent of the drafters. Originalists, on the other hand, consider the meaning of the Constitution as understood by the populace at the time of its founding. Modernists recognize the value of historical perspective but prioritize the contemporary needs of society. Finally, democratic interpretation views the Constitution as a general principle rather than a set of specific guidelines, allowing for flexibility and dynamism.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Textualism | A mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain meaning of the text of a legal document. |

| Originalism | Considers the meaning of the Constitution as understood by the populace at the time of its founding. |

| Judicial Precedent | The most commonly cited source of constitutional meaning is the Supreme Court's prior decisions on questions of constitutional law. |

| Historical Literalism | Interpreting the Constitution with a literal reading of the words, with expert knowledge of their 18th-century meanings. |

| Contemporary Literalism | Interpreting the Constitution with a modern dictionary definition of the words, ignoring precedent and legal dissertation. |

| Democratic Interpretation | Interpreting the Constitution as a general principle, a basic skeleton to be built upon with contemporary vision. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Textualism

Justice Antonin Scalia, who was both a textualist and an originalist, criticized this sort of strict constructionist approach to textualism. He wrote that a text should not be construed strictly or leniently, but reasonably, to contain all that it fairly means. An example of Justice Black's use of textualism in a First Amendment case is his dissent in Dennis v. United States, where the Court held that Congress could, consistent with the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech, criminalize the conspiracy to advocate the forcible overthrow of the U.S.

Historical literalists interpret the Constitution by looking at the contemporary writings of the Framers and the 18th-century meaning of the words. They ignore precedent and legal dissertation, relying solely on the definition of the words. For example, an historical literalist will interpret the militia of the 2nd Amendment as referring to all able-bodied men from 17 to 45, just as in the late 18th century. On the other hand, contemporary literalists look to modern dictionaries to determine the meaning of the words of the Constitution, ignoring historical meaning.

Founding Fathers' Conflicts: Constitution's Challenges

You may want to see also

Original Meaning

Originalists believe that the Constitution's text had an "objectively identifiable" or public meaning at the time of its founding that has not changed over time. The task of judges and justices is to construct this original meaning. Originalists feel that modernism does a disservice to the Constitution, arguing that the people who wrote it had a pure and valid vision for the nation, and that their vision should be able to sustain us through any Constitutional question.

Originalists consider the meaning of the Constitution as it was understood by at least some segment of the population at the time of its founding. This is in contrast to textualist approaches, which focus solely on the text of the document. Textualists usually believe there is an objective meaning to the text and do not typically inquire into questions regarding the intent of the drafters, adopters, or ratifiers of the Constitution and its amendments when deriving meaning from the text. Textualism is a mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain meaning of the text of a legal document. Textualism usually emphasizes how the terms in the Constitution would be understood by people at the time they were ratified, as well as the context in which those terms appear.

Justice Hugo LaFayette Black, who was both a textualist and an originalist, took a strict constructionist approach to textualism. He wrote that the First Amendment's statement that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press" amounted to an absolute command that no law shall be passed by Congress abridging freedom of speech or the press. This form of textualism is sometimes referred to as pure textualism or literalism.

In contrast to originalists, modernists believe that the contemporary needs of society outweigh an adherence to a potentially dangerously outdated angle of attack. They do not reject originalism, however, and recognize that there is value in a historical perspective.

Historical literalists, similar to originalists, believe that the contemporary writings of the Framers are not relevant to any interpretation of the Constitution. They believe that the only thing one needs to interpret the Constitution is a literal reading of the words contained therein, with expert knowledge of the 18th-century meaning of those words. For example, an historical literalist will see the militia of the 2nd Amendment as referring to all able-bodied men from 17 to 45, just as in the late 18th century.

Contemporary literalists, on the other hand, look only to the words of the Constitution for guidance but have no interest in the historical meaning of the words. They look to modern dictionaries to determine the meaning of the words of the Constitution, ignoring precedent and legal dissertation, and relying solely on the definition of the words.

Lincoln's Constitutional Overreach: Congress' Complicity and Consequences

You may want to see also

Judicial Precedent

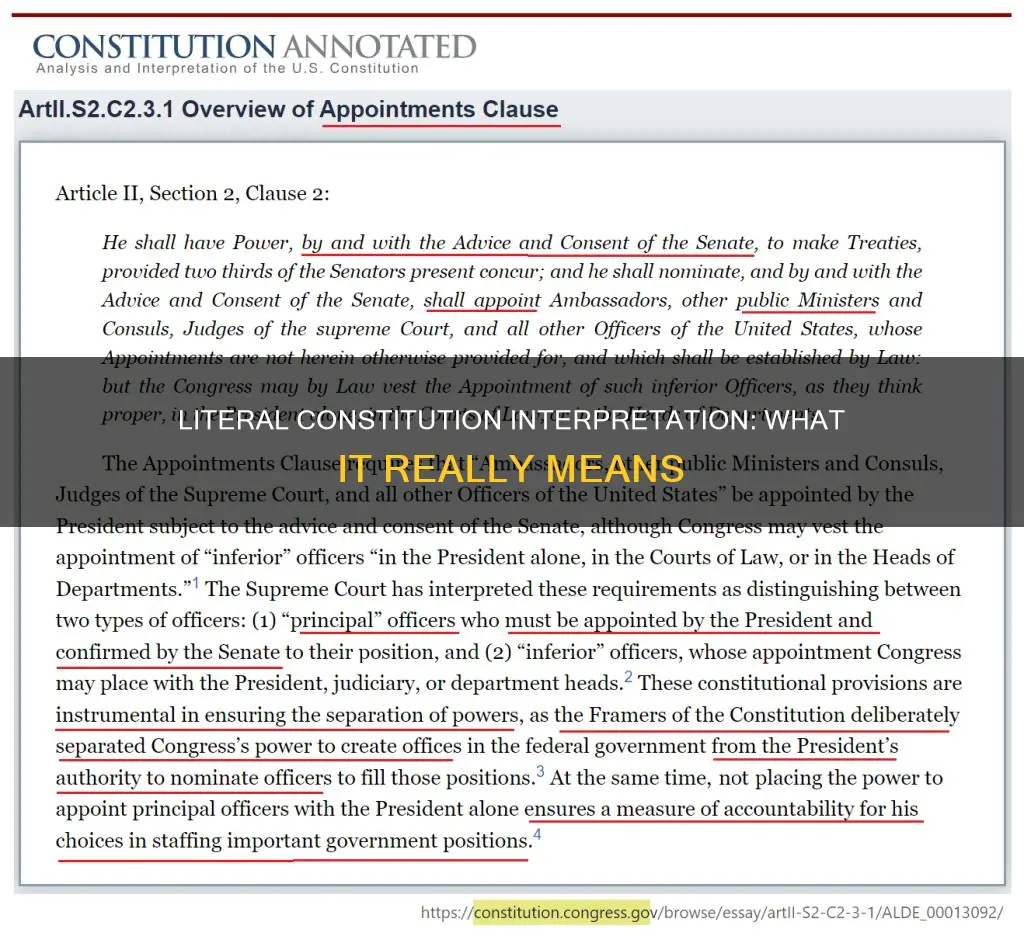

A literal interpretation of the US Constitution, also known as textualism, is a mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain meaning of the text of the legal document. Textualism emphasizes how the terms in the Constitution would have been understood by people at the time of ratification, as well as the context in which those terms appear. Textualists believe there is an objective meaning to the text and do not typically inquire into the intentions of those who drafted, adopted, or ratified the Constitution and its amendments.

In the US, a large body of judicial decisions, or precedents, has been developed over time, especially by the Supreme Court. These precedents inform the Court's future decisions and provide a foundation for future rulings. When reviewing law reports, it is important for legal professionals to understand how to navigate and analyze a law report swiftly, including ascertaining the precedents referred to in drawing the conclusion. A prior decision serves as a precedent only for the issues and particular facts that the court explicitly considered in reaching its decision. Precedent is generally established by a series of decisions, but sometimes a single decision can create a precedent, such as a single statutory interpretation by the highest court of a state.

In contrast to common law systems, civil law systems are characterized by comprehensive codes and detailed statutes, with less emphasis on precedent. Judges in civil law systems primarily focus on fact-finding and applying codified law. However, some civil law systems, such as those in the Nordic countries, may have a mixed system where case law plays a more important role. For example, in Sweden, the two highest courts have the right to set precedent, which has persuasive authority on all future applications of the law.

US and California Constitutions: Similarities and Shared Values

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical Literalism

Literalism, in the context of constitutional interpretation, is often referred to as "pure textualism" or "originalism". It is a mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain or literal meaning of the text of a legal document, such as the Constitution. Textualism emphasizes how the terms in the Constitution would have been understood by the people at the time of its ratification, as well as the context in which those terms appear.

One of the earliest proponents of historical literalism was Justice Hugo Black, who wrote in 1968 that the First Amendment's statement, "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press", was an absolute command that no law shall be passed by Congress abridging freedom of speech or the press. This form of textualism is sometimes referred to as pure textualism or literalism.

Another key figure in historical literalism is Justice Antonin Scalia, who was both a textualist and an originalist. He criticized the strict constructionist approach to textualism, arguing that a text should not be construed strictly or leniently, but reasonably, to contain all that it fairly means. Scalia's view aligns with the concept of original public understanding originalism, which bases the meaning of a constitutional provision on how the ratifying public would have generally understood it.

Hamilton's Critique of Constitution Opponents

You may want to see also

Contemporary Literalism

Contemporary literalists believe that the words of the Constitution should be interpreted using modern dictionaries to determine the current meaning of the words, rather than considering their historical context or the intent of the drafters. This approach is in contrast to originalism, which considers the meaning of the Constitution as understood by the populace at the time of its founding. While originalists believe that the Constitution's text had an "objectively identifiable" or public meaning that has not changed over time, contemporary literalists argue that the contemporary needs of society are more important than adhering to potentially outdated interpretations.

An example of how a contemporary literalist might interpret the Second Amendment illustrates this approach. While an historical literalist would interpret the "militia" of the 2nd Amendment as referring to all able-bodied men from 17 to 45, a contemporary literalist would view the militia as the modern National Guard. This interpretation would then colour their views on the Second Amendment as a whole.

Justice Hugo LaFayette Black, a famous textualist, once wrote about the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech, stating that it amounted to an absolute command that no law shall be passed by Congress abridging freedom of speech or the press. This strict constructionist approach to textualism has been criticised by some, who argue that a text should be interpreted reasonably to contain all that it fairly means, rather than strictly or leniently.

In conclusion, contemporary literalism is a mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain meaning of the text of the Constitution, ignoring historical context and precedent. While it shares similarities with originalism in its focus on the text of the document, it differs in its rejection of historical meanings and its emphasis on modern definitions.

Unethical Oil Business: What's the Real Cost?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A literal interpretation of the Constitution, also known as textualism, is a mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain meaning of the text of the document. Textualists believe there is an objective meaning to the text and do not inquire into the intentions of its drafters.

A historical literalist interprets the Constitution with an expert knowledge of the 18th-century meaning of the words. A contemporary literalist, on the other hand, uses modern dictionaries to determine the meaning of the words, ignoring precedent and legal dissertation.

The Constitution is the oldest continually operating constitution in the world and was written in a time before many modern developments. Therefore, critics argue that it is senseless to try to make legal decisions based on the views of the authors. They also argue that it is not possible to completely remove interpretation from textual analysis, and that the authors of the Constitution were often deliberately vague.

Justice Hugo LaFayette Black, a famous textualist, once wrote that the First Amendment's statement that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press" meant that Congress was absolutely forbidden from enacting any law that would curtail these rights.