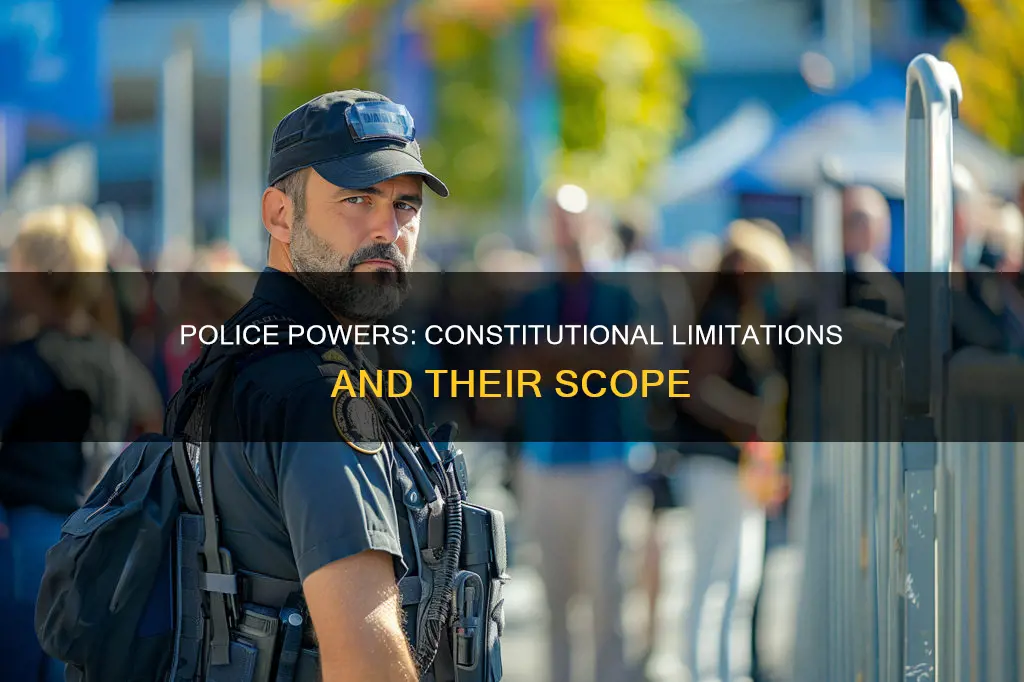

Police power is exercised by the legislative and executive branches of the various states through the enactment and enforcement of laws and regulations. The United States Constitution and state constitutions protect individuals' rights and freedoms, which state police power cannot infringe upon. The Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause extends the Federal Government's power, applying many individual rights protected in the Bill of Rights to the states. The Tenth Amendment further defines the federal police power, stating that powers not delegated to the US Constitution are reserved for the states or the people. Federal police power has been defined by Supreme Court rulings, which have affirmed that Congress has limited power to enact legislation. These rulings have invalidated provisions of federal laws on violent crime and gun possession near schools, demonstrating the constitutional limitations on police power.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Restrictions on police power | Few and far between due to the nebulous definition of police power |

| Constitutional restraints on police power | Laws must apply equally to all under like circumstances |

| Government interference with individual rights | Must be 'reasonable' and have a clear relation to some legitimate legislative purpose |

| State police power | Cannot infringe upon implied constitutional rights |

| Federal police power | Limited by the Constitution, as seen in United States v. Lopez (1995) and United States v. Morrison (2000) |

| State authority conflicts with individual rights and freedoms | Use of police power may be controversial |

| Basis of police power under American Constitutional law | Rooted in English and European common law traditions |

| Tenth Amendment | Powers not delegated to the US by the Constitution are reserved for the States or the people |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Federal police power

The Tenth Amendment of the US Constitution states that "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." This amendment serves as a limitation on federal power, including federal police power.

In the 1995 case of United States v. Lopez, the Supreme Court ruled against a statute prohibiting gun possession near schools, citing that such a law would impair the functioning of the national economy. The Court affirmed that Congress has limited power and does not possess a plenary police power to authorise any type of legislation. This ruling set a precedent for the distinction between national and local matters, preserving the federal government's nature of enumerated and limited powers.

In United States v. Morrison (2000), the Supreme Court further invalidated a provision of federal law concerning violent crime. This decision aligned with the precedent set in United States v. Lopez, reinforcing the limitations on federal police power.

While federal police power is constrained by the Constitution, it is important to note that the definition of police power itself is nebulous, making restrictions on its use relatively scarce. According to historian Michael Willrich, while there are constitutional restraints, they are limited, and government interferences with individual rights must be 'reasonable' and clearly related to a legitimate legislative purpose.

Interesting Facts About the US Constitution

You may want to see also

State police power

Police power is a fundamental principle of federalism, embodied in the US Constitution, which gives states the power to enact and enforce laws and regulations. This power is exercised by the legislative and executive branches of state governments, and it is limited by the state constitution, exclusive federal powers, and fundamental rights protected by the US Constitution.

The Tenth Amendment of the US Constitution states that "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." This amendment has been used by the Supreme Court to invalidate federal laws that infringe on state police powers, particularly in the early 20th century regarding economic regulations.

The Supreme Court has also ruled on the limits of federal police power, affirming that Congress has limited power to enact legislation. For example, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Court ruled that the Constitution withholds a plenary police power from Congress, restricting their ability to authorise all types of legislation.

Despite the broad nature of state police power, there are some constitutional limitations. In Commonwealth v. Alger, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw acknowledged the difficulty of defining the boundaries of police power but recognised that laws must apply equally and that government interferences with individual rights must be reasonable and serve a legitimate legislative purpose. Later court cases have further restricted state power by emphasising the protection of implied constitutional rights.

Palmer Raids: Unconstitutional Violations of Civil Liberties

You may want to see also

Individual rights

The nebulous definition of police power has resulted in few restrictions on its use. However, it is important to recognise that police power is subject to constitutional limitations, particularly when it comes to protecting individual rights.

The US Constitution and state constitutions provide a framework for safeguarding individual rights, and any measures taken by the police must not infringe upon these protected rights. The due process clause and enforcement clause of the 14th Amendment have extended the power of the Federal Government, ensuring that the individual rights protected in the Bill of Rights are upheld by the states. This includes rights related to search and seizure, self-incrimination, and the right to counsel.

Court cases have played a significant role in defining the boundaries of police power. For example, in Commonwealth v. Alger, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw acknowledged the existence of police power while recognising the need for constitutional restraints to ensure that government interferences with individual rights are 'reasonable' and serve a legitimate legislative purpose. Later court cases have further expanded on these restrictions, limiting the ability of states to infringe upon implied constitutional rights.

Federal police power has also been defined by Supreme Court rulings. The court has affirmed that Congress has limited power to enact legislation, and certain federal statutes have been invalidated on the basis that they exceed the power granted to Congress by the Constitution. For instance, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the court ruled against a statute prohibiting the possession of firearms near schools, as it was argued that this would impair the functioning of the national economy. Similarly, in United States v. Morrison (2000), a provision of the Violence Against Women Act was invalidated as it created a federal cause of action for victims of gender-motivated violence, which was seen as undermining the limited powers of the Federal Government.

In conclusion, while police power is a necessary tool for maintaining law and order, it is important to recognise that it is subject to constitutional limitations. These limitations are in place to protect the individual rights and freedoms of citizens, ensuring that any measures taken by the police do not infringe upon the rights guaranteed by the US Constitution and state constitutions.

Uganda's Constitution: Freedom of Speech Examined

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legislative purpose

The legislative purpose of police power is to enable the legislative and executive branches of US states to enact and enforce laws and regulations. This includes the power to compel obedience to these laws through various measures, including legal sanctions and physical means. However, these measures must not infringe upon any rights protected by the US Constitution or individual state constitutions, and they must not be unreasonably arbitrary or oppressive.

The US Constitution and state constitutions impose certain limitations on police power. For example, the Due Process Clause and Enforcement Clause of the 14th Amendment extend the power of the Federal Government and protect individual rights such as those against search and seizure, self-incrimination, and the right to counsel.

The Tenth Amendment also plays a role in shaping the legislative purpose of police power. It reserves for the states or the people those powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution and not prohibited by it to the states. This amendment has been interpreted by the courts in various cases, including Hammer v. Dagenhart, United States v. Darby, and United States v. Lopez, to define the limits of federal police power and uphold the principle of enumerated and limited powers of the Federal Government.

According to historian Michael Willrich, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw recognized certain constitutional restraints on police power in Commonwealth v. Alger. Willrich notes that Shaw acknowledged that laws must apply equally to all under like circumstances and that government interferences with individual rights must be 'reasonable' and clearly related to some legitimate legislative purpose. While later court cases have expanded upon these restrictions, demanding a stricter standard of reasonability, the regulation of police power remains minimal.

Georgia Constitution: Understanding Its Branch Structure

You may want to see also

Constitutional restraints

The concept of police power is nebulous, and its boundaries are challenging to define. However, historian Michael Willrich acknowledged a few constitutional restraints on police power. Firstly, laws must apply equally to all under similar circumstances, without any discrimination. Secondly, government interferences with individual rights must be 'reasonable' and clearly related to a legitimate legislative purpose.

Court cases have expanded on these restrictions, limiting the ability of states to infringe upon implied constitutional rights. For example, in Commonwealth v. Alger, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw recognised the existence of police power but emphasised the need to prevent its unchecked exercise. Similarly, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Court struck down a statute prohibiting gun possession near schools, upholding the distinction between national and local matters and reaffirming the limited nature of federal power.

The Tenth Amendment also plays a role in defining constitutional restraints on police power. It reserves powers to the states or the people that are not delegated to the United States by the Constitution. In Hamilton v. Kentucky Distilleries Co., the Court upheld "War Prohibition," acknowledging that while the United States lacks police power, it can still exert its constitutionally conferred powers without objection, even if similar to state police power.

The due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment extends the protection of individual rights to the states, encompassing search and seizure, self-incrimination, and the right to counsel. These constitutional restraints ensure that state police power is exercised within defined limits, balancing law enforcement with the protection of citizens' liberties.

Key Constitution Points: A Quick Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Police power is exercised by the legislative and executive branches of the various states through the enactment and enforcement of laws and regulations.

The measures enforced by the police must not infringe upon any of the rights protected by the United States Constitution or their own state constitutions and must not be unreasonably arbitrary or oppressive.

Constitutional limitations on police power include the due process clause and enforcement clause of the 14th Amendment, which extend the power of the Federal Government.

Court cases have expanded on the restrictions of police power by limiting the ability of states to infringe upon implied constitutional rights and by demanding a stricter standard of reasonability. For example, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the court ruled that the Constitution withholds from Congress a plenary police power, limiting their ability to enact legislation.

The Tenth Amendment states that powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution are reserved for the States or the people. This has been interpreted to mean that the federal government lacks police power, which is reserved for the states.

![Constitutional Law: [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61R-n2y0Q8L._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Constitutional Law [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61qrQ6YZVOL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Constitutional Law: [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/711lR4w+ZNL._AC_UL320_.jpg)