In a world where political ideologies often dominate public discourse, it’s worth considering the provocative question: what if every political party is wrong? While each party claims to hold the solutions to society’s most pressing issues, their policies and platforms are frequently rooted in partial truths, ideological biases, or short-term interests. The rigid frameworks of left, right, and center often fail to address the complexity of real-world problems, leaving gaps in understanding and action. Moreover, the adversarial nature of party politics can prioritize winning over genuine problem-solving, fostering division rather than unity. What if the answers lie beyond the confines of existing party lines, in innovative, collaborative, or entirely new approaches that challenge the status quo? This question invites us to rethink the foundations of political thought and explore whether the true path forward might require stepping outside the boundaries of traditional partisanship.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Flawed Ideologies: Examining if core beliefs of all parties are fundamentally misguided or outdated

- Systemic Failures: Analyzing if political systems inherently fail to address societal needs effectively

- Polarization Pitfalls: Exploring how partisan divides hinder progress and compromise in governance

- Alternative Models: Investigating non-partisan or hybrid systems as potential solutions to current issues

- Citizen Disillusionment: Understanding why voters increasingly distrust all political parties and their promises

Flawed Ideologies: Examining if core beliefs of all parties are fundamentally misguided or outdated

In the realm of politics, it's not uncommon for individuals to align themselves with a particular party, adopting its core beliefs and values as their own. However, the question arises: what if the fundamental ideologies that underpin these parties are inherently flawed or outdated? This provocative inquiry challenges the very foundation of political discourse, prompting a critical examination of the principles that guide our leaders and shape our societies. When considering the possibility that every political party might be wrong, we must delve into the core tenets of their beliefs, scrutinizing them for inconsistencies, biases, and irrelevance in the face of contemporary challenges.

Upon closer inspection, it becomes apparent that many political ideologies are rooted in historical contexts that no longer reflect the complexities of modern life. For instance, traditional left-wing parties often advocate for centralized planning and wealth redistribution, assuming that these measures will lead to greater equality and social justice. While these goals are undoubtedly noble, the means by which they are pursued may be misguided. Centralized control can stifle innovation, discourage individual initiative, and create bureaucratic inefficiencies that ultimately hinder progress. Similarly, right-wing parties frequently emphasize free-market capitalism and limited government intervention, believing that these principles will foster economic growth and personal freedom. Yet, unchecked capitalism can exacerbate income inequality, environmental degradation, and social fragmentation, revealing the limitations of this ideology.

Furthermore, the core beliefs of political parties often rely on oversimplified assumptions about human nature and societal dynamics. Many parties operate under the notion that their particular ideology holds the key to solving all societal problems, disregarding the multifaceted nature of these issues. For example, some parties may prioritize economic growth above all else, neglecting the importance of environmental sustainability, social cohesion, and individual well-being. Conversely, others may focus solely on social justice, failing to recognize the economic realities and constraints that shape policy decisions. This reductionist approach not only limits the effectiveness of proposed solutions but also contributes to the polarization and gridlock that plague contemporary politics. By acknowledging the complexity and interconnectedness of societal challenges, we can begin to move beyond the constraints of flawed ideologies.

The examination of flawed ideologies also highlights the role of cognitive biases and emotional appeals in shaping political beliefs. Political parties often exploit these psychological tendencies to garner support, framing their policies in ways that resonate with voters' values and fears. However, this approach can lead to the prioritization of short-term gains over long-term sustainability, as well as the marginalization of minority perspectives and interests. Moreover, the tribalism and partisanship that result from such tactics undermine constructive dialogue and compromise, hindering the development of nuanced, evidence-based solutions. To transcend these limitations, it is essential to cultivate a more critical, reflective, and empathetic approach to political discourse, one that prioritizes the common good over partisan interests.

Ultimately, the recognition that every political party might be wrong serves as a catalyst for rethinking the foundations of our political systems. This does not imply that all political ideologies are equally flawed or that there are no valuable insights to be gained from them. Rather, it suggests that a more humble, adaptive, and inclusive approach is needed – one that acknowledges the limitations of existing ideologies and embraces the complexity and uncertainty of the modern world. By engaging in honest, open-minded dialogue across partisan divides, we can begin to identify areas of consensus, develop innovative solutions, and create a more just, sustainable, and prosperous society for all. This process requires courage, curiosity, and a willingness to challenge our own assumptions, but the potential rewards are well worth the effort.

Unveiling the Mystery: Who Was Polito's Driver and Why It Matters

You may want to see also

Systemic Failures: Analyzing if political systems inherently fail to address societal needs effectively

The notion that every political party might be wrong challenges the core assumptions of democratic governance, suggesting that systemic failures within political systems inherently hinder their ability to address societal needs effectively. At the heart of this argument is the observation that political parties, regardless of ideology, often prioritize short-term gains, such as electoral victories or partisan interests, over long-term societal well-being. This misalignment of incentives creates a structural barrier to meaningful progress. For instance, policies are frequently crafted to appeal to specific voter demographics rather than to solve complex, systemic issues like inequality, climate change, or healthcare access. As a result, even when parties claim to represent the public interest, their actions are often constrained by the need to maintain power, leading to incrementalism or gridlock rather than transformative change.

One systemic failure lies in the reductive nature of party politics, which simplifies complex societal problems into binary or partisan debates. This oversimplification obscures nuanced solutions and fosters polarization, making it difficult to build consensus on critical issues. For example, debates over healthcare reform often devolve into ideological battles between public and private systems, rather than focusing on practical, evidence-based improvements. This polarization is exacerbated by the media and political rhetoric, which prioritize conflict over collaboration. Consequently, even when parties are technically "right" in their diagnoses of societal problems, their inability to work across ideological lines renders their solutions ineffective or incomplete.

Another inherent flaw is the influence of special interests and lobbying, which distort the political process and divert resources away from public needs. Political parties, regardless of their platforms, are often beholden to wealthy donors, corporations, or interest groups that shape policy in their favor. This dynamic undermines the principle of representation, as elected officials may prioritize the demands of a narrow elite over the broader population. For instance, policies favoring tax cuts for the wealthy or deregulation of industries often come at the expense of social programs that benefit the majority. This systemic corruption of priorities highlights how political systems, by design, fail to serve the collective good.

Furthermore, the cyclical nature of elections encourages short-term thinking, as politicians focus on immediate results to secure reelection rather than addressing root causes of societal issues. This temporal mismatch between electoral cycles and the long-term nature of many societal challenges means that problems like poverty, education inequality, or environmental degradation are rarely tackled with the urgency they require. Even when parties propose ambitious agendas, they are often constrained by the need to deliver quick wins to maintain public support. This inherent focus on the present perpetuates systemic failures, as the underlying structures that generate societal problems remain unaddressed.

Finally, the globalized nature of many contemporary challenges exposes the limitations of national political systems, which are ill-equipped to address transnational issues like climate change, migration, or pandemics. While these problems demand coordinated, global solutions, political parties are often constrained by nationalistic or protectionist agendas that prioritize domestic interests over international cooperation. This mismatch between the scale of the problem and the scope of political action underscores the systemic inadequacy of current political frameworks. Without fundamental reforms to incentivize collaboration and long-term thinking, political systems will continue to fail in addressing the most pressing needs of society.

In conclusion, the hypothesis that every political party might be wrong is not merely a critique of individual ideologies but a call to examine the systemic failures embedded within political systems themselves. From misaligned incentives and polarization to the influence of special interests and short-termism, these failures reveal inherent limitations in how political parties operate. Addressing societal needs effectively requires not just better policies but a rethinking of the structures and processes that govern political decision-making. Until such systemic reforms are undertaken, the gap between societal needs and political solutions will persist, leaving the question of whether any party can truly be "right" in a flawed system.

Choosing a Political Party in Indiana: Your Rights and Options

You may want to see also

Polarization Pitfalls: Exploring how partisan divides hinder progress and compromise in governance

In the increasingly polarized landscape of modern politics, the notion that every political party might be wrong serves as a provocative starting point for understanding the pitfalls of partisan divides. When political parties become entrenched in their ideologies, they often prioritize party loyalty over objective problem-solving. This rigidity fosters an environment where compromise is seen as a weakness rather than a necessary tool for governance. As a result, policies that could benefit the broader public are stalled or distorted, as parties focus on scoring points against their opponents rather than addressing complex issues. This zero-sum mindset not only hinders progress but also erodes public trust in democratic institutions, as citizens witness their leaders prioritizing partisanship over the common good.

One of the most significant pitfalls of polarization is the tendency to view political opponents as enemies rather than fellow citizens with differing perspectives. This "us vs. them" mentality dehumanizes dissent and stifles constructive dialogue. When every issue becomes a battleground for ideological supremacy, nuanced discussions are replaced by simplistic narratives that reinforce existing biases. For instance, debates on critical topics like healthcare, climate change, or economic policy are often reduced to partisan talking points, leaving little room for evidence-based solutions. This lack of collaboration not only prevents effective governance but also deepens societal divisions, making it harder to find common ground on shared challenges.

Another consequence of partisan polarization is the distortion of reality through echo chambers and misinformation. Political parties and their supporters often exist in information bubbles, consuming media that reinforces their preconceptions while dismissing opposing viewpoints as invalid. This selective exposure to information creates a distorted understanding of reality, where facts are weaponized to serve partisan agendas. When every political party believes it holds a monopoly on truth, the possibility of finding objective solutions diminishes. This dynamic undermines the very foundation of democratic discourse, which relies on informed debate and mutual respect for differing opinions.

Polarization also exacerbates governance challenges by making it difficult to enact long-term policies. In highly polarized systems, short-term political gains often take precedence over sustainable solutions. For example, a party in power might reverse the policies of its predecessor simply to differentiate itself, even if those policies were effective. This cyclical approach to governance wastes resources and creates instability, as policies are constantly being rewritten rather than refined. The result is a lack of continuity and coherence in addressing pressing issues, leaving societies ill-equipped to tackle systemic problems that require consistent, bipartisan efforts.

Finally, the pitfalls of polarization extend beyond governance to the broader social fabric. When political divides become all-consuming, they seep into everyday life, straining relationships and fostering a culture of intolerance. Families, friendships, and communities are fractured as political identities become central to personal identities. This polarization of society not only makes it harder to achieve political compromise but also undermines the sense of unity necessary for a functioning democracy. If every political party is wrong in its refusal to engage with opposing views, the collective cost is a society that struggles to move forward together.

In conclusion, the pitfalls of polarization reveal the dangers of allowing partisan divides to dominate governance. When every political party operates under the assumption that it alone holds the answers, the result is stagnation, division, and a loss of faith in democratic processes. Recognizing that no single party has a monopoly on truth is the first step toward fostering a more collaborative and effective approach to governance. By embracing compromise, encouraging open dialogue, and prioritizing the common good, societies can begin to overcome the polarization that currently hinders progress and unity.

Putin's Political Standing: Power, Influence, and Global Implications Today

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$44.79 $55.99

Alternative Models: Investigating non-partisan or hybrid systems as potential solutions to current issues

The notion that every political party might be wrong challenges us to rethink the fundamental structures of governance. Traditional partisan systems often prioritize ideological purity and party loyalty over pragmatic problem-solving, leading to gridlock, polarization, and policies that fail to address complex, multifaceted issues. This realization prompts an exploration of alternative models—non-partisan or hybrid systems—that could offer more flexible, inclusive, and effective solutions. By investigating these models, we can identify mechanisms that prioritize collaboration, expertise, and citizen engagement over partisan interests.

One promising alternative is the non-partisan governance model, where elected officials are not bound by party affiliations. This system, exemplified in countries like Singapore or local governments in the United States, emphasizes meritocracy and technocratic decision-making. Without party constraints, leaders can focus on evidence-based policies and long-term planning rather than short-term political gains. For instance, Singapore’s success in economic development and social welfare can be attributed to its non-partisan approach, which fosters stability and adaptability. However, critics argue that such systems may lack ideological diversity and accountability, highlighting the need for robust checks and balances to ensure transparency and citizen representation.

Hybrid systems, which combine elements of partisan and non-partisan governance, offer another viable path. For example, deliberative democracy integrates citizen participation with expert input to shape policies. Models like citizens’ assemblies or participatory budgeting, as seen in Ireland and Brazil, empower ordinary people to engage directly in decision-making. These systems reduce the dominance of political elites and encourage policies that reflect the collective will of the population. By blending participatory mechanisms with traditional institutions, hybrid systems can bridge the gap between government and citizens while maintaining political accountability.

Another innovative approach is the issue-based coalition model, where parties or groups form alliances based on specific policy goals rather than broad ideologies. This system, akin to the Danish or Swiss political landscapes, allows for dynamic and issue-specific collaborations. For instance, a coalition might form to address climate change, drawing support from diverse parties without requiring alignment on unrelated issues. This model fosters pragmatism and flexibility, enabling governments to tackle complex problems with tailored solutions. However, it requires a political culture that values cooperation over competition, which may be challenging to cultivate in deeply polarized societies.

Finally, technocratic governance, while controversial, merits consideration as a hybrid model. Here, experts in relevant fields—scientists, economists, engineers—play a central role in policymaking, supported by elected representatives who ensure democratic legitimacy. Estonia’s e-governance system, which leverages technology and expertise to streamline public services, is a practical example. While technocracy risks sidelining public opinion, it can be balanced by mechanisms like referendums or advisory councils to maintain citizen involvement. This model is particularly appealing for addressing technical or global challenges, such as pandemics or climate change, where specialized knowledge is critical.

In conclusion, the exploration of non-partisan and hybrid systems reveals a spectrum of alternatives to traditional partisan governance. These models—non-partisan technocracy, deliberative democracy, issue-based coalitions, and technocratic hybrids—offer innovative ways to address the shortcomings of current political systems. By prioritizing collaboration, expertise, and citizen engagement, they can foster more effective, inclusive, and responsive governance. The challenge lies in adapting these models to diverse cultural, social, and political contexts, ensuring they remain democratic, accountable, and aligned with the needs of the people. If every political party is wrong, these alternative models provide a roadmap for reimagining governance in the 21st century.

Understanding Global Dynamics: The Importance of Studying International Politics

You may want to see also

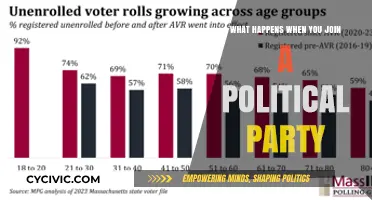

Citizen Disillusionment: Understanding why voters increasingly distrust all political parties and their promises

In recent years, a growing number of voters have expressed profound disillusionment with political parties across the ideological spectrum. This phenomenon is not confined to any single country or political system; it is a global trend fueled by a combination of systemic failures, unfulfilled promises, and a widening gap between political rhetoric and tangible outcomes. Citizens are increasingly questioning whether any political party genuinely represents their interests or if they are all, in some way, misguided or self-serving. This skepticism is rooted in the perception that parties prioritize power, ideology, or special interests over the common good, leaving voters feeling alienated and betrayed.

One major driver of this disillusionment is the consistent failure of political parties to deliver on their campaign promises. Voters often find themselves caught in a cycle of hope and disappointment as parties make bold commitments during elections, only to backtrack or fail to implement them once in power. This pattern erodes trust and reinforces the belief that politicians are more concerned with winning elections than with governing effectively. For instance, issues like economic inequality, climate change, and healthcare reform often remain unresolved despite being central to numerous party platforms, leading citizens to wonder if any party truly has the solutions they claim.

Another factor contributing to citizen disillusionment is the hyper-partisan nature of modern politics. Parties increasingly engage in divisive rhetoric and polarizing tactics to solidify their base, often at the expense of constructive dialogue and compromise. This approach not only stifles progress on critical issues but also creates an "us vs. them" mentality that alienates moderate and independent voters. When every party seems more focused on attacking its opponents than on proposing viable solutions, it becomes difficult for citizens to trust that any of them are genuinely working in their best interests.

The influence of money and special interests in politics further deepens voter distrust. Many citizens perceive that political parties are beholden to wealthy donors, corporations, or lobbyists rather than to the electorate. This perception is reinforced by instances of policy decisions that favor powerful interests over the needs of ordinary people. As a result, voters feel that their voices are drowned out by those with financial clout, leading to a sense of powerlessness and cynicism about the entire political process.

Finally, the rapid spread of misinformation and the rise of echo chambers in the digital age have exacerbated disillusionment. Citizens are often bombarded with conflicting narratives, making it difficult to discern truth from propaganda. Political parties, too, are accused of manipulating information to suit their agendas, further eroding trust. In this environment, voters are left questioning whether any party is genuinely committed to transparency and accountability, or if they are all complicit in a system that prioritizes manipulation over honesty.

In conclusion, citizen disillusionment with political parties stems from a complex interplay of unfulfilled promises, partisan divisiveness, the influence of special interests, and the challenges of the information age. As voters increasingly doubt that any party has the right answers, there is a growing call for a reevaluation of how politics is conducted. Addressing this disillusionment requires systemic reforms that prioritize transparency, accountability, and genuine representation of citizen interests. Until then, the question of whether every political party is wrong will continue to resonate with a public desperate for leadership they can trust.

Markets Unfazed: How Global Economies Thrive Despite Political Turmoil

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It means that no single political party may have all the correct solutions or fully represent the complexities of societal issues, potentially leading to incomplete or flawed policies.

By critically evaluating their policies, track records, and alignment with evidence-based solutions, while also considering diverse perspectives beyond party lines.

It could lead to ineffective governance, polarization, and failure to address pressing issues like climate change, inequality, or economic instability.

Yes, as parties often prioritize ideology, partisan interests, or short-term gains over practical, long-term solutions, leading to collective shortcomings.

Engage in independent research, support non-partisan initiatives, advocate for evidence-based policies, and consider cross-party or independent candidates.