After the War of 1812, the American political landscape underwent significant transformation, particularly for the Federalist Party, which had opposed the war and suffered a severe decline in popularity. The Federalists' association with the Hartford Convention, where some members discussed secession, alienated them from the public, leading to their eventual dissolution as a national force. In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like James Madison and James Monroe, emerged dominant, enjoying a period often referred to as the Era of Good Feelings. This era was marked by reduced partisan conflict and a sense of national unity, though regional and ideological differences began to resurface by the late 1820s, setting the stage for the Second Party System. The war's aftermath thus reshaped American politics, consolidating power in one party while rendering another obsolete.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dominant Party Post-War | The Democratic-Republican Party dominated American politics after the War of 1812, leading to the "Era of Good Feelings." |

| Decline of Federalists | The Federalist Party declined sharply due to its opposition to the war and the Hartford Convention, which was perceived as unpatriotic. |

| One-Party System | The U.S. temporarily became a one-party system under President James Monroe, as the Federalists faded and factions within the Democratic-Republicans had not yet solidified. |

| Emergence of Factions | Internal divisions within the Democratic-Republican Party began to emerge, laying the groundwork for the Second Party System in the 1820s and 1830s. |

| Sectionalism | Regional interests began to shape political alignments, with North-South divisions becoming more pronounced over issues like tariffs and slavery. |

| Rise of New Leaders | Leaders like Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams gained prominence, eventually leading to the formation of the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. |

| Economic Policies | Post-war politics focused on nationalism, infrastructure (e.g., roads, canals), and economic development, influenced by Henry Clay's American System. |

| Western Expansion | The war's outcome encouraged western expansion, which became a key political issue, influencing party platforms and policies. |

| Public Sentiment | A surge in national pride and unity temporarily reduced partisan conflict, though it was short-lived as new issues arose. |

| Legacy of the War | The war's outcome strengthened American identity and reduced British influence, shaping political priorities and party agendas. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Rise of the Democratic-Republican Party

The War of 1812 significantly reshaped the American political landscape, setting the stage for the rise of the Democratic-Republican Party as the dominant political force in the United States. Prior to the war, the Federalist Party, which had advocated for a strong central government and close ties with Britain, saw its influence wane due to its opposition to the war and its perceived lack of patriotism. In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like James Madison and James Monroe, gained popularity by supporting the war and championing states' rights and agrarian interests. The war's conclusion, despite its mixed outcomes, was framed by Democratic-Republicans as a victory for American independence and sovereignty, bolstering their appeal to the electorate.

The Era of Good Feelings, which followed the War of 1812, further solidified the Democratic-Republican Party's dominance. During this period, the Federalists failed to recover from their wartime unpopularity, and their influence dwindled to the point of near irrelevance. With little organized opposition, the Democratic-Republicans enjoyed a monopoly on national politics. James Monroe's presidency (1817–1825) epitomized this era, as he ran virtually unopposed in both the 1816 and 1820 elections. The party's platform, emphasizing limited federal government, westward expansion, and support for farmers, resonated widely with the American public, particularly in the growing frontier regions.

However, the very success of the Democratic-Republican Party sowed the seeds of its eventual fragmentation. Without a strong opposing party, internal divisions began to emerge over key issues such as the role of the federal government, tariffs, and the expansion of slavery. These tensions became particularly evident during the Missouri Crisis of 1819–1821, which highlighted the growing rift between northern and southern factions within the party. Despite these internal challenges, the Democratic-Republicans maintained their hold on power, but the party's unity was increasingly strained.

The rise of the Democratic-Republican Party also coincided with significant changes in American politics, including the expansion of suffrage and the emergence of new political styles. The party capitalized on the growing democratization of politics, appealing to a broader base of voters beyond the elite classes. This shift was reflected in the rise of charismatic leaders like Andrew Jackson, who would later break away to form the Democratic Party. The Democratic-Republicans' ability to adapt to these changes allowed them to remain dominant, even as the political landscape evolved.

By the late 1820s, the Democratic-Republican Party began to splinter into distinct factions, laying the groundwork for the Second Party System. The emergence of the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, led by Henry Clay, marked the end of the Democratic-Republicans' undisputed dominance. Nonetheless, the party's legacy was profound, as it shaped American political ideology and institutions during a critical period of national growth and transformation. Its rise and eventual fragmentation underscored the dynamic and often contentious nature of early American politics.

Understanding Political Hacks: Tactics, Impact, and Modern Influence

You may want to see also

Decline of the Federalist Party

The War of 1812 marked a significant turning point in American political history, particularly for the Federalist Party, which had been a dominant force in the early years of the republic. The Federalists, who had strongly opposed the war with Britain, found themselves increasingly isolated and out of step with the prevailing national sentiment. Their stance on the war, characterized by their support for the Hartford Convention in 1814—where New England Federalists discussed secession and voiced grievances against the war and the Democratic-Republican Party—alienated them from the broader American public. This convention was widely perceived as unpatriotic, especially after the war concluded with a sense of national pride and unity following the Battle of New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent. The Federalists' actions during this period severely damaged their reputation and public support, setting the stage for their decline.

The Federalist Party's opposition to the War of 1812 was rooted in their economic and regional interests, particularly in New England, where the war disrupted maritime trade and harmed the local economy. However, their resistance to the war effort and their perceived lack of patriotism contrasted sharply with the Democratic-Republicans, led by James Madison, who rallied national support for the conflict. The Federalists' inability to adapt their message to the post-war mood of the country further marginalized them. The "Era of Good Feelings," which followed the war, was marked by a surge in national unity and a decline in partisan politics, leaving little room for the Federalists' divisive rhetoric. This period saw the Democratic-Republicans dominate the political landscape, as they capitalized on the war's aftermath to consolidate power and marginalize their opponents.

Another critical factor in the Federalists' decline was their failure to attract new supporters or retain their existing base. The party's leadership, which included figures like Rufus King and Harrison Gray Otis, struggled to articulate a compelling vision for the nation beyond their opposition to the war and their defense of New England's economic interests. Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans, under the leadership of figures like James Monroe, successfully portrayed themselves as the party of national unity and progress. The Federalists' inability to compete with this narrative, coupled with their association with elitism and regionalism, made it difficult for them to appeal to a broader electorate. As a result, the party began to lose ground in both state and federal elections, with their representation in Congress dwindling significantly by the early 1820s.

The final blow to the Federalist Party came with the rise of new political issues and the realignment of American politics in the post-war era. The emergence of the Second Party System, dominated by the Democratic-Republicans and the newly formed Whig Party, left little space for the Federalists. Their policies and ideologies, which had been shaped by the challenges of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, no longer resonated with the changing needs and aspirations of the American people. The Federalists' failure to adapt to these shifts, combined with their tarnished reputation from the War of 1812, ensured their decline into political irrelevance. By the late 1820s, the Federalist Party had effectively ceased to exist as a national political force, its legacy overshadowed by the rise of new parties and ideologies that would shape American politics for decades to come.

In summary, the decline of the Federalist Party after the War of 1812 was a result of their misjudgment of the national mood, their regional focus, and their inability to adapt to the changing political landscape. Their opposition to the war and involvement in the Hartford Convention alienated them from the public, while the Democratic-Republicans capitalized on the post-war unity to dominate politics. The Federalists' failure to broaden their appeal and their inability to compete with emerging political narratives sealed their fate, leading to their eventual disappearance from the American political scene. This decline marked the end of the First Party System and paved the way for the development of new political alignments in the United States.

Understanding Racial Identity Politics: Power, Representation, and Social Justice

You may want to see also

Emergence of the Whig Party

The War of 1812 significantly reshaped the American political landscape, leading to the decline of the Federalist Party and the temporary dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party. However, this post-war era also sowed the seeds for the emergence of the Whig Party, which would become a major force in American politics during the 1830s and 1840s. The Whig Party arose as a response to the growing power of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party, which had succeeded the Democratic-Republicans. Jackson's policies, particularly his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States and his use of executive power, alarmed many political leaders who feared the concentration of authority in the presidency.

The immediate precursor to the Whig Party was the National Republican Party, formed in the early 1820s by supporters of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. This group advocated for a strong federal government, internal improvements, and a national bank—policies that contrasted sharply with Jackson's states' rights and limited government philosophy. After Jackson's election in 1828, his actions, such as the veto of the Maysville Road Bill and his war on the Bank of the United States, further galvanized opposition. By the early 1830s, this coalition of National Republicans, disaffected Democrats, and former Federalists began to coalesce under the banner of the Whig Party, named after the British Whigs who opposed monarchical power.

The Whigs framed themselves as the defenders of constitutional liberty against what they saw as Jackson's tyrannical tendencies. They criticized Jackson's use of executive power, particularly his removal of federal deposits from the Bank of the United States and his defiance of the Supreme Court in the Cherokee removal crisis. The Whigs also championed a program of economic modernization, including support for tariffs, internal improvements, and a national bank, which they believed would promote economic growth and national unity. This platform appealed to a broad coalition of Northern industrialists, Western farmers seeking infrastructure development, and Southern planters who supported protective tariffs.

The emergence of the Whig Party was formalized in the mid-1830s, with Henry Clay as its most prominent leader. Clay's "American System," which emphasized the interconnectedness of tariffs, internal improvements, and a national bank, became the party's economic blueprint. The Whigs also capitalized on public dissatisfaction with Jackson's policies, particularly his handling of the Panic of 1837, which they blamed on his destruction of the Bank of the United States. By the 1840 election, the Whigs had successfully mobilized a diverse coalition, electing William Henry Harrison as president, though his death shortly after taking office and the subsequent presidency of John Tyler presented new challenges for the party.

Despite internal divisions and the transient nature of some of its coalitions, the Whig Party played a crucial role in shaping American politics during the Second Party System. It provided a viable opposition to the Democratic Party and advanced a vision of active federal government that would influence later political movements, including the Republican Party. The Whigs' emphasis on economic development, constitutional restraint, and opposition to executive overreach left a lasting legacy, even as the party itself dissolved in the 1850s over the issue of slavery. The emergence of the Whig Party thus marked a critical phase in the evolution of American political parties after the War of 1812, reflecting the nation's ongoing debates about governance, economic policy, and the balance of power.

Healthcare and Politics: Unraveling the Complex Intersection of Policy and Care

You may want to see also

Explore related products

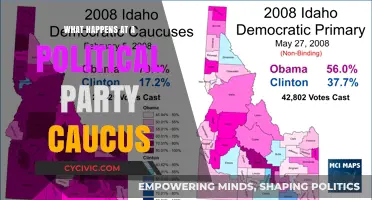

Sectionalism and Party Realignment

The War of 1812 marked a turning point in American politics, setting the stage for significant changes in the nation's political landscape. In the years following the war, the United States experienced a period of intense sectionalism, where regional interests and identities began to dominate political discourse. This sectionalism was driven by economic, social, and cultural differences between the North and the South, as well as the West, which was rapidly expanding. The Federalist Party, which had opposed the War of 1812, saw its influence wane, particularly in the South and West, where it was viewed as elitist and out of touch with the needs of the common people. This decline created a vacuum that would lead to the realignment of political parties.

The Era of Good Feelings, which followed the war, was initially characterized by a sense of national unity under President James Monroe and the dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party. However, this unity was superficial, as underlying tensions between regions persisted. The Democratic-Republicans, once a cohesive force, began to fracture along sectional lines. Northern and Southern factions within the party increasingly clashed over issues such as tariffs, internal improvements, and, most critically, the expansion of slavery into new territories. These divisions laid the groundwork for the emergence of new political alignments that would better reflect regional interests.

The Tariff of 1828, often called the "Tariff of Abominations" by Southerners, exemplified the growing sectional divide. While the North supported protective tariffs to foster industrial growth, the South opposed them, as they increased the cost of imported goods and harmed the agrarian economy. This issue, combined with disagreements over the Missouri Compromise and the admission of new states as slave or free, deepened the rift between Northern and Southern politicians. As a result, the Democratic-Republican Party began to splinter, with Northern and Southern leaders increasingly pursuing their own regional agendas.

The Second Party System emerged in the late 1820s and early 1830s as a direct result of this sectionalism and party realignment. The Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, appealed to Western and Southern voters with its emphasis on states' rights, limited federal government, and opposition to elitism. In contrast, the Whig Party, which drew support from the North and some Southern nationalists, advocated for a stronger federal government, internal improvements, and protective tariffs. This realignment reflected the growing polarization between regions and their competing economic and ideological interests.

By the mid-1830s, the political landscape had been fundamentally transformed. Sectionalism had become the dominant force in American politics, shaping party platforms, electoral strategies, and legislative priorities. The issues of slavery, economic policy, and states' rights continued to drive wedges between the North and South, setting the stage for further conflict in the decades leading up to the Civil War. The realignment of political parties after the War of 1812 was not merely a reshuffling of factions but a reflection of the deep-seated regional divisions that would define American politics for generations.

Todd Baxter's Political Dilemma: Should He Change Parties?

You may want to see also

Impact of the Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings, which followed the War of 1812, was a period marked by a significant shift in the American political landscape. This era, spanning from 1815 to 1825, saw the temporary decline of partisan politics and the dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party, led by President James Monroe. The war's conclusion had fostered a sense of national unity and pride, as the United States had successfully defended itself against a major world power, Britain. This newfound patriotism contributed to the erosion of the Federalist Party, which had opposed the war and was subsequently perceived as unpatriotic by many Americans. As a result, the Federalists' influence waned, and they failed to win any significant elections during this period.

One of the most notable impacts of the Era of Good Feelings was the emergence of a one-party system. With the Federalists marginalized, the Democratic-Republicans became the sole dominant political force. This lack of partisan competition allowed President Monroe to pursue his policies with relative ease, as there was little organized opposition. The era saw the passage of significant legislation, including the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which temporarily resolved the issue of slavery in the new territories. However, the absence of a strong opposing party also meant that there was limited debate and scrutiny of government actions, which some historians argue led to a degree of political complacency.

The economic policies of the Monroe administration further shaped the impact of this era. The federal government adopted a more nationalist approach, promoting internal improvements such as roads and canals, which were seen as essential for national growth and unity. The Panic of 1819, a severe economic depression, did challenge this sense of prosperity, but it also highlighted the need for more robust financial regulations. The era's focus on economic development and infrastructure laid the groundwork for future industrialization and expansion, though it also exacerbated regional tensions, particularly between the North and the South, over issues like tariffs and banking policies.

Socially and culturally, the Era of Good Feelings fostered a sense of national identity and optimism. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 symbolized the nation's progress and interconnectedness, boosting morale and economic activity. This period also saw the rise of cultural nationalism, with American literature and art beginning to flourish independently from European influences. However, this era of apparent harmony masked underlying divisions, particularly regarding slavery and states' rights, which would later resurface and lead to significant political realignments.

In conclusion, the Era of Good Feelings had a profound impact on American political parties and the nation as a whole. It led to the temporary dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party and the decline of the Federalists, creating a one-party system that facilitated legislative action but limited political debate. The era's economic and cultural developments strengthened national unity and identity, yet they also sowed the seeds of future conflicts. This period of relative calm and progress ultimately gave way to the reemergence of partisan politics and the formation of new political alignments in the late 1820s, as the issues of slavery and regional interests became increasingly divisive.

Red in Politics: Unraveling the Party Behind the Color

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

After the War of 1812, the Federalist Party, which had opposed the war, declined significantly in influence. The Democratic-Republican Party, led by James Madison and later James Monroe, dominated national politics, leading to the "Era of Good Feelings."

Yes, the Federalist Party's opposition to the War of 1812, including their perceived lack of patriotism during the Hartford Convention, alienated many voters. By the early 1820s, the party had largely dissolved, leaving the Democratic-Republicans as the dominant political force.

The Democratic-Republican Party became less unified after the war, as internal factions began to emerge. These divisions eventually led to the formation of new parties, such as the Democratic Party under Andrew Jackson and the Whig Party in the late 1820s and 1830s.

The post-war surge in American nationalism, often referred to as the "Era of Good Feelings," temporarily reduced partisan conflict. However, as economic and regional issues resurfaced, nationalism gave way to renewed political divisions, setting the stage for the Second Party System.

No new parties were formed immediately after the war, but the decline of the Federalists and the fragmentation of the Democratic-Republicans laid the groundwork for the emergence of the Democratic and Whig Parties in the 1820s and 1830s.