A state political subdivision refers to a geographically defined area within a state that has been granted authority to govern itself under state law. These subdivisions, which include counties, municipalities, townships, school districts, and special districts, are established to provide localized governance and essential public services tailored to the needs of their residents. They operate as extensions of state government, exercising powers delegated by the state constitution or statutes, while also maintaining a degree of autonomy in decision-making. Understanding state political subdivisions is crucial for grasping how governance is structured at the local level, how resources are allocated, and how policies are implemented to address community-specific issues.

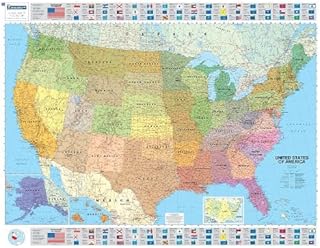

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Counties and Parishes: Administrative divisions providing local governance, services, and representation within a state

- Municipalities and Cities: Incorporated areas with self-governance, managing local affairs and infrastructure

- Townships and Towns: Smaller political units offering localized services and community governance

- Special Districts: Entities created for specific purposes like schools, water, or fire services

- Census Designated Places: Unincorporated areas defined for statistical purposes, lacking formal governance

Counties and Parishes: Administrative divisions providing local governance, services, and representation within a state

Counties and parishes serve as the backbone of local governance in many states, acting as intermediaries between state authority and municipal or individual needs. These administrative divisions are not merely bureaucratic constructs but vital frameworks that ensure services like law enforcement, public health, and infrastructure maintenance reach communities effectively. For instance, in the United States, counties manage elections, maintain roads, and operate social services, while parishes in Louisiana perform similar functions with a unique cultural and historical twist. Understanding their roles clarifies how decentralized governance can adapt to local demands while upholding state-level policies.

Consider the practical implications of these divisions. In rural areas, where municipalities are sparse, counties often assume responsibilities that cities handle independently, such as waste management or emergency services. This adaptability ensures that even remote populations receive essential services. However, this system is not without challenges. Funding disparities between affluent and impoverished counties can lead to unequal service quality, highlighting the need for state oversight and equitable resource allocation. For residents, knowing which services their county or parish provides can streamline access to public resources and foster civic engagement.

A comparative analysis reveals intriguing differences between counties and parishes. While both are administrative units, parishes in Louisiana retain a distinct identity rooted in the state’s French and Spanish colonial history. This historical context influences not only their nomenclature but also their governance structures, often blending traditional practices with modern administrative requirements. In contrast, counties across other states follow a more standardized model, though variations in authority and jurisdiction exist. For example, some counties have home rule, allowing greater autonomy in decision-making, while others operate under stricter state control.

To maximize the benefits of these divisions, citizens should actively participate in local governance. Attending county or parish board meetings, engaging in public forums, and voting in local elections are actionable steps to influence policy and service delivery. Additionally, leveraging digital tools—such as county websites or apps—can provide real-time updates on services, public notices, and community initiatives. For those in leadership roles, prioritizing transparency and accountability ensures these divisions fulfill their mandate of representing and serving their constituents effectively.

In conclusion, counties and parishes are more than administrative labels; they are dynamic entities that shape the daily lives of millions. By understanding their functions, challenges, and opportunities, individuals can better navigate local systems and advocate for improvements. Whether through historical quirks or modern adaptations, these divisions demonstrate the resilience and flexibility of localized governance in addressing diverse community needs.

Understanding the Role of the Non-Political Executive in Governance

You may want to see also

Municipalities and Cities: Incorporated areas with self-governance, managing local affairs and infrastructure

Municipalities and cities are the backbone of local governance, serving as the primary units of self-governance within state political subdivisions. These incorporated areas are granted the authority to manage their own affairs, from zoning laws to public services, creating a tailored approach to community needs. For instance, a city council in Austin, Texas, can enact ordinances specific to its population density and cultural priorities, such as green energy initiatives or public transportation expansions, without waiting for state-level approval. This autonomy ensures that decisions are made closer to the people they affect, fostering a sense of ownership and responsiveness.

Incorporation is the legal process that transforms a community into a municipality or city, endowing it with the power to tax, regulate, and provide essential services like water, sanitation, and emergency response. This status is not automatic; it requires a formal application and approval process, often involving a vote by residents. Once established, these entities operate under a charter or bylaws that outline their structure, powers, and limitations. For example, a small municipality in rural Maine might focus on maintaining local roads and preserving historic landmarks, while a bustling city like Chicago prioritizes complex urban planning and economic development. The key is adaptability—each incorporated area tailors its governance to its unique challenges and opportunities.

The infrastructure managed by municipalities and cities is vast and varied, encompassing everything from parks and libraries to sewage systems and power grids. Effective management requires strategic planning, budgeting, and collaboration with state and federal agencies. Take the case of Miami, Florida, where city officials must balance the demands of tourism-driven growth with the need for resilient infrastructure to combat rising sea levels. Here, self-governance allows for innovative solutions, such as public-private partnerships for waterfront development or local bond measures to fund flood mitigation projects. This localized control ensures that infrastructure investments align with the community’s long-term vision.

Critics argue that self-governance can lead to inefficiencies or inequities, particularly in underresourced areas. Smaller municipalities may struggle to fund essential services, while wealthier cities thrive. However, this challenge also highlights the importance of state oversight and inter-municipal cooperation. For instance, regional councils in Ohio allow neighboring cities to pool resources for shared services like waste management or emergency dispatch. Such collaborative models demonstrate that self-governance need not operate in isolation; it can be strengthened through strategic partnerships. Ultimately, municipalities and cities embody the principle of local control, empowering communities to shape their own destinies while navigating the complexities of modern governance.

Understanding Comparative Politics: A Comprehensive Essay Guide

You may want to see also

Townships and Towns: Smaller political units offering localized services and community governance

Townships and towns represent the grassroots of American governance, serving as the smallest political subdivisions in many states. These entities are often the first point of contact between citizens and their government, providing essential services like road maintenance, waste management, and local zoning. Unlike larger municipalities, townships and towns operate on a hyper-local scale, allowing for more direct citizen involvement in decision-making processes. This proximity fosters a sense of community and ensures that local needs are addressed with precision and care.

Consider the example of New England towns, which have been a cornerstone of local governance since colonial times. These towns operate under the town meeting form of government, where registered voters gather annually to debate and vote on local issues, from school budgets to road repairs. This model exemplifies the power of localized governance, as it empowers residents to have a direct say in matters that affect their daily lives. In contrast, townships in the Midwest often focus on specific services like fire protection or park maintenance, leaving broader responsibilities to county governments. Understanding these regional variations is key to appreciating the diversity of township and town governance across the U.S.

For those looking to engage with their local government, townships and towns offer a practical starting point. Attending town hall meetings, joining local boards or commissions, or simply staying informed about upcoming elections can make a significant difference. For instance, in townships with elected boards of trustees, residents can run for office or advocate for specific initiatives. Even small actions, like participating in community clean-up days or volunteering for local projects, contribute to the overall well-being of the area. These units of government thrive on citizen participation, making them an ideal platform for those seeking to make a tangible impact.

However, townships and towns are not without challenges. Limited budgets and resources often constrain their ability to address complex issues, such as infrastructure upgrades or economic development. Additionally, the volunteer-driven nature of many township governments can lead to burnout or inefficiencies. To mitigate these issues, some townships have explored intergovernmental agreements, sharing services with neighboring municipalities to maximize efficiency. Others have embraced technology, using digital platforms to streamline communication and engage younger residents. By adapting to modern challenges, townships and towns can continue to serve as vital pillars of local governance.

In conclusion, townships and towns embody the principle of localized governance, offering a unique blend of community engagement and practical service delivery. Their small scale allows for direct citizen involvement, fostering a sense of ownership and accountability. While they face challenges, their adaptability and focus on community needs make them indispensable components of state political subdivisions. Whether through participation, advocacy, or innovation, residents can play a crucial role in ensuring these smaller political units remain effective and responsive to local demands.

Understanding Political Speech: Definition, Importance, and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.47 $13.95

Special Districts: Entities created for specific purposes like schools, water, or fire services

Special Districts are a unique form of state political subdivision, designed to address specific local needs that might not be efficiently managed by broader county or municipal governments. These entities are created to provide essential services such as education, water supply, fire protection, and sanitation, often with a high degree of specialization and autonomy. For instance, a school district focuses solely on educational services, allowing for targeted funding and administration that aligns with the community’s academic goals. Similarly, a water district manages the local water supply, ensuring infrastructure maintenance and resource sustainability. This specialization enables Special Districts to operate with precision, addressing niche challenges that general-purpose governments might overlook.

Consider the practical implications of establishing a Special District. The process typically begins with identifying a specific need within a community, such as inadequate fire services in a rural area. Local residents or government officials petition the state legislature to create a new district, outlining its purpose, boundaries, and funding mechanisms. Once approved, the district gains the authority to levy taxes, issue bonds, and enforce regulations within its jurisdiction. For example, a fire district might impose a property tax to fund equipment upgrades and firefighter training. This localized control ensures that resources are allocated directly to the identified need, minimizing bureaucratic inefficiencies.

One of the key advantages of Special Districts is their ability to tailor services to the unique characteristics of their communities. A water district in a drought-prone region, for instance, can implement conservation programs and invest in desalination technology, whereas a district in a water-rich area might focus on flood control. This adaptability is particularly valuable in diverse states where one-size-fits-all solutions are impractical. However, this flexibility comes with challenges. Special Districts can sometimes overlap with other jurisdictions, leading to confusion over responsibilities and duplication of efforts. For example, a county and a Special District might both claim authority over stormwater management, requiring careful coordination to avoid conflicts.

Critics argue that the proliferation of Special Districts can lead to fragmentation in governance, making it difficult for residents to understand who is responsible for what. In California, for instance, there are over 3,000 Special Districts, ranging from mosquito abatement to cemetery maintenance. This complexity can complicate accountability and transparency, as each district operates independently with its own board and budget. To mitigate these issues, some states have implemented oversight mechanisms, such as requiring districts to submit annual financial reports or undergo periodic performance audits. Residents can also play a role by staying informed about their local districts and participating in board elections to ensure their interests are represented.

In conclusion, Special Districts serve as a vital tool for addressing specific local needs within the framework of state political subdivisions. Their specialized focus allows for targeted solutions, from improving school systems to managing natural resources. However, their effectiveness depends on careful planning, clear boundaries, and robust oversight. By understanding how these entities function and engaging with them proactively, communities can maximize the benefits of Special Districts while minimizing potential drawbacks. Whether advocating for a new district or holding an existing one accountable, informed participation is key to ensuring these entities fulfill their intended purpose.

Laughing at the Absurd: Decoding the Hilarious World of Political Jokes

You may want to see also

Census Designated Places: Unincorporated areas defined for statistical purposes, lacking formal governance

Census Designated Places (CDPs) are a unique category within the broader framework of state political subdivisions, serving a specific yet crucial role in data collection and analysis. Unlike incorporated cities or towns, CDPs are unincorporated areas that lack formal local governance structures such as mayors, city councils, or municipal services. Instead, they are defined solely for statistical purposes by the U.S. Census Bureau to provide detailed demographic data for areas that resemble towns or neighborhoods but do not have legal or governmental autonomy. This distinction is vital for understanding how CDPs fit into the mosaic of state political subdivisions.

Consider the practical implications of CDPs in data-driven decision-making. For instance, during the allocation of federal funding or the planning of public services, accurate population counts and demographic profiles are essential. CDPs ensure that these unincorporated areas are not overlooked, even though they lack formal governance. A CDP like Fishers, Indiana, before its incorporation in 2010, was treated statistically as a distinct place, allowing policymakers to assess its needs for infrastructure, education, and healthcare. This example underscores the CDP’s role as a bridge between unincorporated areas and the statistical frameworks that drive resource distribution.

However, the lack of formal governance in CDPs presents challenges. Residents of these areas often rely on county governments for services like law enforcement, road maintenance, and zoning, which can lead to disparities in service quality and responsiveness. For instance, a CDP in a rural county may struggle to secure adequate funding for local projects compared to incorporated towns with dedicated tax revenues. This governance gap highlights the trade-off between the statistical utility of CDPs and the practical limitations they impose on residents.

To navigate these complexities, stakeholders must approach CDPs with a dual lens: recognizing their value in data collection while addressing their governance shortcomings. One actionable step is for county governments to establish advisory boards or committees specific to CDPs, ensuring resident voices are heard in decision-making processes. Additionally, state legislatures could explore mechanisms to grant CDPs limited self-governance powers, such as managing local budgets or initiating community projects. These measures would enhance the functionality of CDPs without necessitating full incorporation, striking a balance between statistical precision and local autonomy.

In conclusion, Census Designated Places are a critical yet often overlooked component of state political subdivisions. Their role in providing granular demographic data is indispensable, but their lack of formal governance demands thoughtful solutions. By understanding the unique challenges and opportunities CDPs present, policymakers, residents, and planners can work collaboratively to ensure these areas are both accurately represented and effectively served. This nuanced approach transforms CDPs from mere statistical constructs into vibrant, recognized communities within the broader state landscape.

Do Political Refugees Pay Taxes? Understanding Their Fiscal Responsibilities

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A state political subdivision refers to a geographic or jurisdictional division within a state, such as counties, cities, towns, villages, school districts, or special districts, that has the authority to perform specific governmental functions.

Examples include counties, municipalities (cities and towns), townships, school districts, utility districts, and other special-purpose districts created by state law.

They are important because they provide localized governance, deliver essential services (e.g., education, public safety, infrastructure), and allow for more responsive decision-making tailored to specific communities.

They are typically created through state legislation or by following procedures outlined in state constitutions, often requiring voter approval or meeting specific criteria for establishment.

Their powers are granted by the state and can include taxing authority, land use regulation, public service provision, and enforcement of local ordinances, though these powers vary by jurisdiction and state law.