A single political party system, often referred to as a one-party state or dominant-party system, is a political structure in which one political party holds a monopoly on power, either by law or through practical dominance, effectively eliminating meaningful competition from opposition parties. This system contrasts sharply with multi-party democracies, where multiple parties compete for electoral victory and governance. In a one-party system, the ruling party typically controls key institutions, such as the legislature, judiciary, and media, often blurring the lines between the party and the state. While proponents argue that such systems can foster stability and unity, critics highlight the risks of authoritarianism, lack of accountability, and suppression of dissent, raising questions about the balance between order and individual freedoms in governance.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Single-Party Dominance: One party holds continuous power, often limiting political competition and opposition

- Ideological Unity: Shared beliefs and goals unify the party, shaping policies and governance

- Voter Behavior: Supporters align with the party’s ideology, influencing electoral outcomes consistently

- Lack of Alternatives: Absence of strong opposition reduces voter choice and political diversity

- Stability vs. Stagnation: Consistent rule ensures stability but risks policy rigidity and corruption

Single-Party Dominance: One party holds continuous power, often limiting political competition and opposition

Single-party dominance refers to a political system where one political party holds continuous and often uncontested power over a government, typically for an extended period. This phenomenon is characterized by the party's ability to maintain control through various means, which can include electoral victories, strategic manipulation of political institutions, or even authoritarian measures. In such systems, the dominant party becomes the central pillar of political authority, shaping policies, controlling resources, and often limiting the ability of opposition parties to challenge their rule effectively. This dominance can arise from historical, cultural, or structural factors, such as a party's role in a liberation struggle, its control over key economic sectors, or its ability to mobilize mass support through patronage networks.

One of the key features of single-party dominance is the marginalization of political competition. The dominant party often employs legal, institutional, or extralegal mechanisms to restrict the growth and influence of opposition parties. This can include gerrymandering, restrictive election laws, control over media outlets, or even direct intimidation and suppression of opposition figures. As a result, elections in such systems may appear competitive but are often skewed in favor of the ruling party, leading to a lack of genuine political pluralism. The opposition, if it exists, is frequently weakened, fragmented, or co-opted, leaving little room for alternative voices or policies to emerge.

The continuity of power in single-party dominant systems often leads to the consolidation of control over state institutions. The party in power tends to appoint loyalists to key positions in the judiciary, bureaucracy, and security forces, effectively blurring the lines between the party and the state. This fusion of party and state apparatus ensures that the dominant party's policies and interests are prioritized, often at the expense of accountability and transparency. Over time, this can erode democratic norms and practices, as the ruling party becomes less responsive to public demands and more focused on maintaining its grip on power.

Single-party dominance also has significant implications for governance and policy-making. With limited opposition, the ruling party may pursue its agenda without meaningful checks and balances, leading to policies that favor its supporters or elites aligned with its interests. This can result in inequality, corruption, and inefficiency, as there is little incentive for the party to address broader societal needs or engage in self-correction. Moreover, the absence of robust political competition can stifle innovation and adaptability in governance, as the party may become complacent or resistant to change.

Finally, the persistence of single-party dominance raises questions about political legitimacy and citizen engagement. While the ruling party may claim to represent the will of the people, its prolonged hold on power can lead to disillusionment and apathy among the electorate. Citizens may feel that their votes do not matter or that the political system is rigged against them, undermining trust in democratic institutions. In some cases, this can fuel social unrest or calls for systemic change, as people seek alternatives to break the monopoly of power held by the dominant party. Understanding single-party dominance is crucial for analyzing the dynamics of political systems where one party's continuous rule shapes the contours of governance, competition, and representation.

Mastering Political Strategies: Insights from 'What It Takes' Book

You may want to see also

Ideological Unity: Shared beliefs and goals unify the party, shaping policies and governance

In a one-party political system, ideological unity is the cornerstone that binds the party together, ensuring a cohesive and focused approach to governance. This unity stems from shared beliefs and goals that are deeply ingrained in the party’s ideology. Members of the party, from leaders to grassroots supporters, align themselves with a common vision, which serves as the foundation for all policy decisions and governance strategies. This shared ideology eliminates internal divisions, allowing the party to act as a unified entity with a clear direction. Without competing factions or conflicting interests, the party can prioritize its core principles and implement policies that reflect its overarching mission.

The strength of ideological unity lies in its ability to shape policies that are consistent and predictable. Since all members adhere to the same set of values, there is little room for ambiguity or contradiction in policy formulation. For instance, if a party’s ideology emphasizes economic equality, its policies will consistently aim to reduce wealth disparities, promote social welfare, and regulate markets to ensure fairness. This consistency not only reinforces the party’s credibility but also fosters public trust, as citizens can anticipate the party’s stance on various issues. Ideological unity thus becomes a tool for effective governance, enabling the party to deliver on its promises without internal hindrances.

Moreover, ideological unity ensures that governance is driven by long-term goals rather than short-term political expediency. In a one-party system, the absence of electoral competition allows the party to focus on implementing its vision without the pressure of immediate political gains. This long-term perspective is crucial for addressing complex issues such as climate change, economic development, or social reform, which require sustained effort and commitment. The party’s shared ideology acts as a guiding framework, ensuring that every decision aligns with its ultimate objectives, even if it means making unpopular choices in the short run.

However, ideological unity also demands a mechanism for internal dialogue and consensus-building. While the party may share core beliefs, there can still be nuances or differing interpretations among members. Effective leadership must facilitate open discussions to reconcile these differences and maintain unity. This internal cohesion is vital for preventing fragmentation and ensuring that the party speaks with one voice. By fostering a culture of collaboration and mutual respect, the party can harness the diversity of thought within its ranks while staying true to its ideological foundations.

In conclusion, ideological unity is the lifeblood of a one-party political system, providing the shared beliefs and goals that unify its members and shape its policies and governance. This unity enables consistency, predictability, and a long-term focus, which are essential for effective governance. However, it also requires careful management to ensure that internal differences are resolved constructively. When maintained successfully, ideological unity transforms a political party into a powerful instrument for realizing its vision and serving the public interest.

Ohio Independents: Can You Sign Nominating Petitions for Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Voter Behavior: Supporters align with the party’s ideology, influencing electoral outcomes consistently

In a one-party political system, a single political party dominates the government, often with no legal or practical room for opposition parties to gain power. This structure fundamentally shapes voter behavior, as supporters typically align closely with the party’s ideology, which becomes the primary—if not sole—framework for political participation. In such systems, the party’s ideology is not just a set of beliefs but a guiding principle that influences policies, governance, and societal norms. Voters who identify with the party’s ideology are more likely to consistently support its candidates and policies, as there are no alternative parties to divert their allegiance. This alignment ensures that electoral outcomes remain predictable and stable, reinforcing the party’s dominance.

Supporters of the ruling party in a one-party system often view their alignment as a matter of civic duty or ideological conviction rather than a choice among competing options. The party’s ideology is disseminated through education, media, and public discourse, creating a shared understanding of what constitutes "correct" political thought. Voters internalize these ideas, and their behavior at the polls reflects this indoctrination. For instance, in countries like China under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), voters who align with socialist principles consistently support the party, as its ideology is presented as the only viable path for national development. This ideological alignment minimizes dissent and ensures that electoral outcomes consistently favor the ruling party.

The consistency in voter behavior in one-party systems is also reinforced by the lack of viable alternatives. Without opposition parties to challenge the ruling party’s ideology, voters have little incentive to deviate from their established political alignment. Even if individuals have minor disagreements with specific policies, the overarching ideology often serves as a unifying force. For example, in North Korea, the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) promotes Juche ideology, which emphasizes self-reliance and national sovereignty. Voters who believe in these principles consistently support the WPK, as no other party exists to offer a different vision. This uniformity in voter behavior ensures that electoral outcomes remain unchanged, solidifying the party’s control.

However, the alignment of supporters with the party’s ideology does not necessarily imply genuine enthusiasm or active participation. In some one-party systems, voter behavior is driven by coercion, fear of repercussions, or apathy rather than ideological commitment. For instance, in authoritarian regimes, citizens may vote for the ruling party out of fear of punishment or to maintain social stability. Despite this, the outward consistency in electoral outcomes persists, as the party’s ideology remains the only publicly acceptable framework. This superficial alignment still influences electoral results, maintaining the appearance of unanimous support for the ruling party.

In summary, voter behavior in a one-party system is characterized by strong alignment with the party’s ideology, which consistently influences electoral outcomes. Supporters view the party’s ideology as the cornerstone of political life, and the absence of opposition parties leaves no room for ideological divergence. Whether driven by genuine belief, social pressure, or fear, this alignment ensures that the ruling party maintains its dominance through predictable and stable electoral results. Understanding this dynamic is crucial to grasping the meaning and implications of a one-party political system.

Political Parties vs. Interest Groups: Key Differences and Roles Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

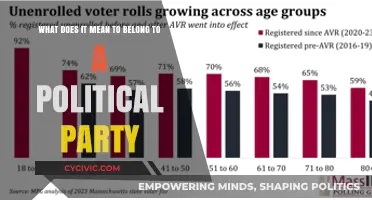

Lack of Alternatives: Absence of strong opposition reduces voter choice and political diversity

In a political system dominated by a single party, the absence of strong opposition significantly diminishes voter choice, as citizens are often left with limited or no meaningful alternatives during elections. This lack of alternatives arises because the ruling party faces little to no credible challenge, allowing it to consolidate power without the need to adapt to diverse public preferences. Voters are then forced to either support the dominant party, abstain from voting, or cast protest votes with little impact. This scenario undermines the democratic principle of free and fair elections, where competition between parties is essential to reflect the spectrum of societal views. Without robust opposition, the political landscape becomes a monopoly, stifling the very essence of democratic choice.

The reduction in voter choice directly contributes to a decline in political diversity, as the dominant party’s ideology and policies become the de facto norm. Minority perspectives, alternative solutions, and innovative ideas are marginalized or excluded from public discourse. This homogenization of political thought limits the system’s ability to address complex societal issues comprehensively. For instance, debates on critical topics such as economic reform, social justice, or environmental policy become one-sided, with little room for dissent or alternative approaches. As a result, the political system becomes less representative of the population’s varied interests and values, leading to alienation and disengagement among voters who feel their voices are not heard.

The absence of strong opposition also weakens accountability mechanisms within the political system. Without a credible challenger, the ruling party may become complacent, prioritizing its own interests over those of the public. Corruption, inefficiency, and authoritarian tendencies can flourish unchecked, as there is no viable force to expose wrongdoing or hold the government accountable. This erosion of accountability further diminishes public trust in political institutions, creating a vicious cycle where citizens become increasingly disillusioned with the democratic process. The lack of alternatives thus not only reduces voter choice but also undermines the health and integrity of the political system as a whole.

Moreover, the absence of strong opposition stifles political innovation and adaptability. In a competitive political environment, parties are compelled to evolve, refine their policies, and respond to changing societal needs to remain relevant. However, in a one-party dominant system, there is little incentive for the ruling party to innovate or reform. This stagnation can lead to outdated policies, ineffective governance, and a failure to address emerging challenges. The lack of alternatives, therefore, not only limits immediate voter choice but also hampers the long-term ability of the political system to serve its citizens effectively.

Finally, the absence of strong opposition has profound implications for civic engagement and political participation. When voters perceive that their choices have no real impact, they are less likely to engage in the political process, whether through voting, activism, or public discourse. This apathy further weakens the democratic fabric, as a vibrant democracy relies on an informed and active citizenry. The lack of alternatives thus creates a self-perpetuating cycle of disengagement, where the absence of opposition leads to reduced participation, which in turn reinforces the dominance of the single party. Addressing this issue requires deliberate efforts to foster political pluralism, strengthen opposition parties, and ensure that voters have genuine choices that reflect the diversity of their society.

Understanding Political Theory: Foundations, Concepts, and Real-World Applications

You may want to see also

Stability vs. Stagnation: Consistent rule ensures stability but risks policy rigidity and corruption

In a one-party political system, a single party dominates governance, often with little to no opposition. This structure inherently prioritizes stability by minimizing political conflict and ensuring consistent policy direction. With no competing parties to challenge its authority, the ruling party can implement long-term plans without the interruptions that come with frequent changes in leadership or ideological shifts. For instance, countries like China, under the Communist Party, have leveraged this stability to pursue decades-long economic and infrastructure development strategies. However, this consistency comes at a cost: the absence of opposition can lead to policy rigidity, as there are fewer mechanisms to challenge or refine existing policies. Without the pressure to adapt or innovate, the ruling party may become complacent, clinging to outdated approaches that fail to address evolving societal needs.

The lack of political competition in a one-party system also heightens the risk of corruption. When a single party holds unchecked power, accountability mechanisms weaken, and opportunities for abuse of power multiply. Officials may exploit their positions for personal gain, knowing there is little to no opposition to expose or challenge their actions. For example, in some one-party states, corruption has become systemic, with resources diverted away from public welfare and into the hands of party elites. This not only undermines public trust but also stifles economic growth and social progress. The stability provided by consistent rule can thus degenerate into stagnation, as corruption erodes the very foundations of governance.

On the other hand, stability in a one-party system can foster a sense of predictability, which is often attractive to investors and citizens alike. Businesses thrive in environments where policies are consistent and long-term planning is feasible. Similarly, citizens may appreciate the absence of political turmoil, especially in regions with a history of instability. However, this predictability can become a double-edged sword if it leads to complacency and resistance to change. Without the dynamism that comes from competing ideas, the system may fail to respond effectively to crises or shifting global realities, resulting in stagnation rather than progress.

To mitigate the risks of policy rigidity and corruption, some one-party systems introduce internal checks and balances, such as factional competition within the party or limited public participation. These measures aim to create a semblance of accountability and encourage innovation. However, their effectiveness depends on the ruling party's willingness to self-regulate, which is not always guaranteed. Ultimately, the tension between stability and stagnation in a one-party system hinges on the party's ability to balance consistency with adaptability and to maintain integrity in the face of unchecked power.

In conclusion, while a one-party system offers the advantage of stability through consistent rule, it inherently risks policy rigidity and corruption. The absence of opposition can lead to complacency and abuse of power, turning stability into stagnation. Striking a balance requires internal reforms and a commitment to accountability, but these are often challenging to achieve in practice. As such, the long-term viability of a one-party system depends on its ability to evolve and address these inherent risks without sacrificing the stability it promises.

Political Power Surge: Impact on Rising Migration Trends Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

"One political party" refers to a political system where only a single party dominates or is legally allowed to hold power, often with little or no opposition.

Not necessarily. While some one-party systems are dictatorial, others may allow limited internal debate or local elections, though ultimate power remains with the single party.

Examples include China (Communist Party), North Korea (Workers' Party of Korea), and Cuba (Communist Party of Cuba), where the ruling party maintains control over government and politics.

Critics argue that one-party systems often lack political pluralism, suppress dissent, limit individual freedoms, and can lead to corruption and inefficiency due to the absence of meaningful opposition.