Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who conquered the Aztec Empire in the early 16th century. He was born in 1485 in Medellín, Spain, and set sail for Hispaniola (modern-day Dominican Republic and Haiti) in 1504, in search of adventure and riches. In 1511, he joined an expedition to Cuba led by Diego Velázquez, and later received permission to lead an expedition to Mexico in 1518. Despite Velázquez cancelling the trip, Cortés defied his orders and set sail for Mexico with around 600 men and 11 ships. Upon his arrival in 1519, he employed diplomacy and force to establish alliances with indigenous peoples, ultimately rallying thousands of native allies to support his conquest of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Diplomacy | Used diplomacy to persuade the Tlaxcalans to join him in his war against the Aztecs |

| Used diplomacy to supplement his force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors | |

| Used diplomacy to gain intelligence from the local Indians | |

| Used diplomacy to establish a colony in Mexico | |

| Used diplomacy to ally with some indigenous people against others | |

| Used diplomacy to rally native allies |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Cortés' diplomacy with the Tlaxcalans

Hernán Cortés was a gifted leader and a skilled diplomat who seized every opportunity presented to him in the New World. He made clever use of diplomacy to supplement his small force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors, sweeping all before him. One of his most pivotal alliances was with the Tlaxcalans, a fierce and independent tribe that had been in conflict with the Aztecs.

The Tlaxcalans were a confederation of semi-autonomous villages united by their hatred of the Aztecs, who had tried repeatedly to conquer and subjugate them. When Cortés and his men first encountered the Tlaxcalans, they impressed the tribal leaders with their military prowess, particularly their gunpowder weapons, horses, and war strategy, which were novel to the indigenous people. Recognizing the opportunity to turn their struggles against the Aztecs into an offensive alliance with Cortés, the Tlaxcalans eventually agreed to join forces with him.

Cortés demonstrated remarkable diplomatic acumen during his dealings with the Tlaxcalans. He emphasized the shared enemy of the Aztecs, a narrative that resonated deeply with the Tlaxcalans, who had suffered under Aztec rule. By presenting himself as a liberator rather than an invader, Cortés was able to frame the Spanish incursion as a campaign against a common oppressor. This narrative was critical in persuading the Tlaxcalans to side with him.

The alliance with the Tlaxcalans was not merely a military collaboration but a complex relationship involving negotiation, mutual benefit, and adaptation. It brought invaluable local knowledge, as the Tlaxcalans were familiar with the geography, culture, and warfare tactics of their Aztec neighbors. This insight allowed Cortés to plan assaults that often caught the Aztecs off guard. The Tlaxcalans also provided thousands of warriors, significantly bolstering the Spanish forces. This alliance transformed the dynamics of power in Mesoamerica and had lasting repercussions for both the indigenous peoples and the Spanish colonizers.

International Diplomacy: Funding Your Master's Degree

You may want to see also

Diplomacy with the Aztecs

Hernán Cortés was a gifted leader and conqueror who, in addition to superior weapons and tactics, relied on diplomacy to supplement his small force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors. He understood the value of diplomacy and used it to achieve his ends without resorting to battle.

Cortés's first act of diplomacy was to ally with the local Indian peoples, particularly the Tlaxcalans, who were in a state of chronic war with Montezuma II, the ruler of the Aztec empire. He persuaded the Tlaxcalans to join him in his war against the Aztecs. The joint forces of Tlaxcala and Cortés proved to be formidable. One by one, they took over most of the cities under Aztec control, some in battle, others by diplomacy. The Tlaxcaltecs became Cortés's most faithful ally.

Cortés also used a native woman, Doña Marina, as an interpreter and mistress. She bore him a son, and her knowledge of Nahuatl, a Maya dialect, and Spanish, was instrumental in his diplomatic negotiations.

When Cortés arrived in Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, on November 8, 1519, he was received with great honour by Montezuma, in accordance with the diplomatic customs of Mexico. Initially, relations were friendly, and valuable gifts were exchanged. However, two weeks later, diplomacy broke down when Cortés took Montezuma hostage to achieve the political and religious conquest of the Aztecs. The Spanish wanted treasure, and Montezuma was forced to swear himself a subject of the King of Spain. Cortés also ordered the idols of the Aztec gods to be replaced with Christian icons and announced that the temple would never again be used for human sacrifice.

During the siege of Tenochtitlan, Cortés attempted to end the conflict through diplomacy, but all offers were rejected. The city was eventually captured on August 13, 1521, marking the fall of the Aztec Empire and the beginning of Spanish rule in central Mexico.

Campaign Advisors: The Political Strategists and Their Roles

You may want to see also

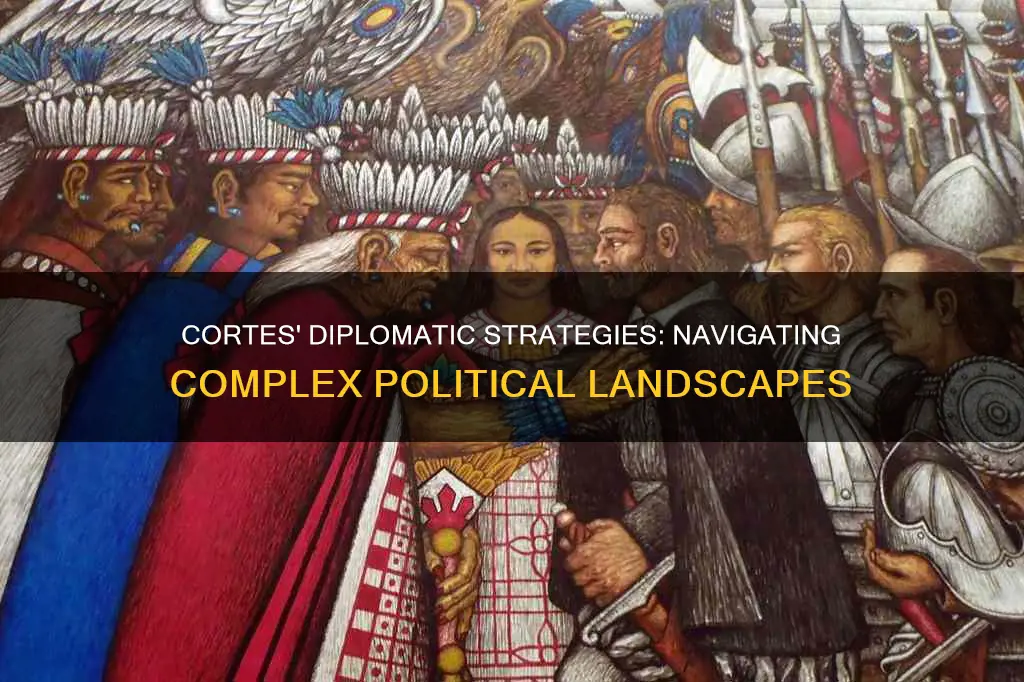

Diplomacy with the Franciscans

Hernán Cortés was a gifted leader of men, and he seized every opportunity presented to him in the New World. Using superior weapons and tactics, he supplemented his meagre force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors. He was also able to display his mastery of diplomacy, persuading the Tlaxcalans to join him in his war against the Aztecs.

The Franciscans, a group of related mendicant religious orders of the Catholic Church, arrived in Mexico in May 1524. This group of twelve, known as the Twelve Apostles of Mexico, was led by Fray Martín de Valencia. The Franciscans were a symbolically powerful group, and their arrival was an important moment in Hernán Cortés's dealings with diplomacy.

Cortés met this first group of Franciscans as they approached the capital, kneeling at their feet in a display of piety and humility. This powerful message to all, including the Indians, demonstrated that Cortés's earthly power was subordinate to the spiritual power of the friars. The conqueror's ability to grasp the political crisis within the Aztec empire, as well as his quick mastery of diplomacy, ultimately gave him more than 200,000 Indian allies.

The Franciscans saw Cortés as "the new Moses" for conquering Mexico and opening it to Christian evangelization. This strong alliance between Cortés and the Franciscans was significant in the former's conquests and influence in Mexico. The ability to communicate with potential allies, as well as his skill in diplomacy, were key factors in Cortés's success in the New World.

Political Parties: Effective Campaign Strategies for Election Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Diplomacy with Velázquez

Hernán Cortés, a Spanish conquistador, is known for his role in the conquest of the Aztec Empire and claiming Mexico for Spain in the 16th century. He was born in 1485 in Medellín, Spain, to a family of minor nobility. At the age of 14, he was sent to study law at the University of Salamanca but dropped out after two years, seeking a life of adventure and riches in the New World.

In 1511, Cortés joined an expedition to Cuba led by Diego Velázquez, where he served as clerk to the treasurer. He received an encomienda, which granted him the right to the labour of certain subjects, and became a notary and farmer in Hispaniola. By 1518, Velázquez, now the governor of Cuba, appointed Cortés as captain-general of an expedition to Mexico. However, due to growing jealousy and suspicions about Cortés' power and influence, Velázquez cancelled the voyage at the last minute.

Displaying defiance and a strong will, Cortés ignored Velázquez's orders and set sail for Mexico in 1519 with about 600 men and 11 ships. He established a colony in Veracruz, where he was elected captain-general and chief justice by his soldiers, further asserting his authority and independence from Velázquez. This act of disobedience towards his superior marked a significant step in Cortés' pursuit of his ambitions and his willingness to challenge established authority.

Cortés' actions in Mexico, including his successful diplomacy with the Tlaxcalans and the capture of Montezuma, the Aztec ruler, ultimately led to the fall of the Aztec Empire. Despite his rivalry with Velázquez, Cortés' leadership, strategic alliances, and determination to pursue his goals played a crucial role in shaping the course of events during this period.

Campaign Strategies: Political Office Guide

You may want to see also

Diplomacy with the Native Americans

Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who led an expedition to Mexico in 1519. He was born in 1485 in Medellín, Spain, to a family of minor nobility. He studied law at the University of Salamanca before deciding to pursue a life of adventure and riches in the New World.

Cortés was a gifted leader who used diplomacy, superior weapons, and tactics to supplement his small force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors. He was also interested in converting Native Americans to Christianity. Upon reaching the Mexican coast, Cortés gained intelligence from the local Indians and won them over with gifts. He then established a colony in Mexico and rallied native allies to support his conquest of the Aztec Empire.

One of Cortés's most notable diplomatic maneuvers was his ability to persuade the Tlaxcalans, a nation that was in a state of chronic war with Montezuma II, the ruler of the Aztec Empire, to join him in his war against the Aztecs. Cortés entered Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, on November 8, 1519, with his small Spanish force and only 1,000 Tlaxcaltecs. Montezuma, thinking Cortés and his men were envoys from the god Quetzalcoatl, treated him as an honored guest. Seizing the opportunity, Cortés took Montezuma hostage, and his soldiers raided the city.

Another example of Cortés's diplomacy with the Native Americans was his alliance with the Franciscans, a group of twelve friars known as the Twelve Apostles of Mexico. The Franciscans saw Cortés as "the new Moses" for conquering Mexico and opening it to Christian evangelization. Cortés met the friars as they approached the capital, kneeling at their feet to demonstrate his piety and humility and to show that his power was subordinate to their spiritual authority.

Treasury Diplomacy: Accessing the Keys to Financial Relations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hernán Cortés was born in 1485 in Medellín, Spain, to a family of lower nobility. He studied law at the University of Salamanca from the age of 14 but dropped out after two years as he was unhappy and craved a life of action. He decided to pursue adventure and riches in the New World, setting sail for Hispaniola (modern-day Dominican Republic and Haiti) in 1504 at the age of 19.

Hernán Cortés is best known for conquering the Aztecs and claiming Mexico on behalf of Spain. In 1519, he led an expedition to Mexico, where he formed alliances with some indigenous peoples against others, supplementing his small force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors. He also used diplomacy to persuade the Tlaxcalans to join him in his war against the Aztecs. In November 1519, he entered Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, with a small Spanish force and 1,000 Tlaxcaltecs, taking ruler Montezuma II hostage.

When Cortés learned that a Spanish force from Cuba, led by Pánfilo Narváez, was arriving to strip him of his command and arrest him for disobeying orders, he fled the city. He left a garrison of 80 Spaniards and a few hundred Tlaxcaltecs under the command of Pedro de Alvarado. While Cortés was away, Alvarado massacred Aztec chiefs, and a rebellion broke out. Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan but was eventually driven out by the Aztecs. He returned again in 1521 to defeat the Aztecs and take the city.

Cortés spent much of his later years seeking recognition for his achievements and support from the Spanish royal court. He participated in an expedition against Algiers in 1541 but fell heavily into debt as a result. He died in Seville, Spain, in 1547 at the age of 62.