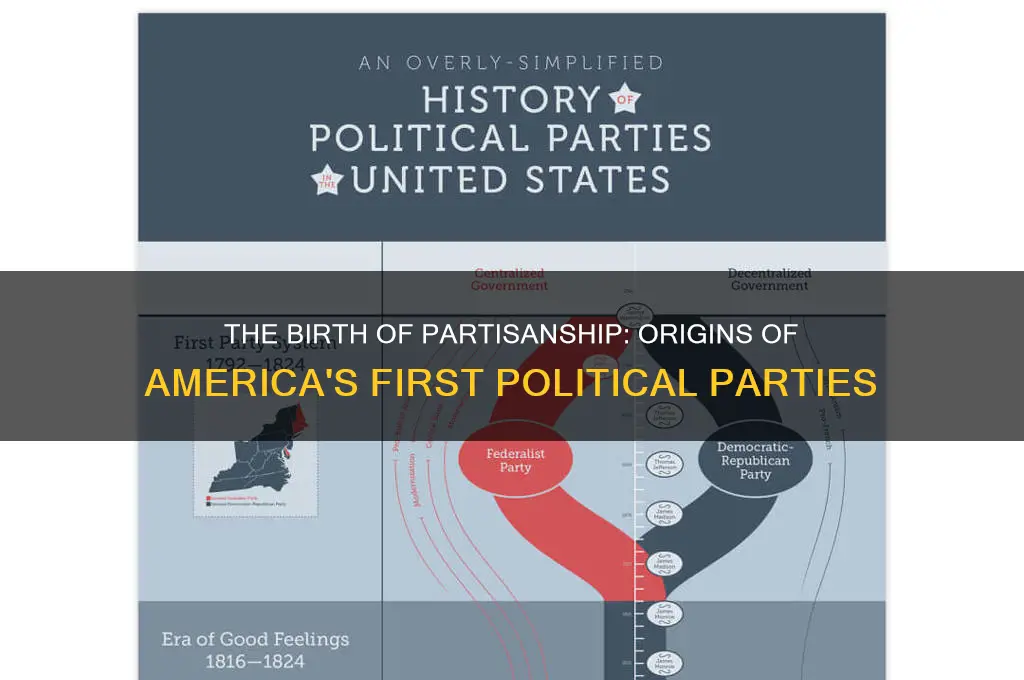

The emergence of the first two political parties in the United States can be traced back to the early years of the nation's independence, during the 1790s, as disagreements over the role and structure of the federal government deepened. The Federalist Party, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain, while the Democratic-Republican Party, spearheaded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government. These divisions were fueled by debates over the Constitution, economic policies, and foreign relations, ultimately solidifying the two-party system that would shape American politics for decades to come.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | The first two political parties in the U.S. emerged during George Washington's presidency (1789–1797). |

| Parties | Federalist Party and Democratic-Republican Party. |

| Key Figures | Federalists: Alexander Hamilton, John Adams. Democratic-Republicans: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison. |

| Ideological Divide | Federalists: Strong central government, pro-commerce, pro-Bank of the U.S. Democratic-Republicans: States' rights, agrarian interests, anti-centralization. |

| Economic Views | Federalists: Supported industrialization and financial institutions. Democratic-Republicans: Favored agriculture and opposed national debt. |

| Foreign Policy | Federalists: Pro-British, neutral in the French Revolution. Democratic-Republicans: Pro-French, opposed British influence. |

| Constitutional Interpretation | Federalists: Loose construction (broad interpretation of the Constitution). Democratic-Republicans: Strict construction (limited federal power). |

| Support Base | Federalists: Urban merchants, bankers, New England. Democratic-Republicans: Farmers, Southern and Western states. |

| Major Legislation | Federalists: Established national bank, excise tax. Democratic-Republicans: Opposed Federalist policies, pushed for states' rights. |

| Legacy | Laid the foundation for the two-party system in American politics. |

Explore related products

$21.87 $26.5

What You'll Learn

- Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist Debates: Disputes over Constitution ratification sparked early party divisions

- Hamilton’s Financial Plans: Federalists supported national bank; Anti-Federalists opposed centralized economic policies

- Washington’s Neutrality: First President’s non-partisan stance indirectly fueled party formation

- Foreign Policy Differences: Federalists pro-British; Democratic-Republicans favored France during global conflicts

- Jefferson vs. Adams: 1796 election solidified two-party system with distinct ideologies

Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist Debates: Disputes over Constitution ratification sparked early party divisions

The emergence of the first two political parties in the United States was deeply rooted in the debates surrounding the ratification of the Constitution. These debates pitted Federalists against Anti-Federalists, creating divisions that would shape the nation's early political landscape. The Federalist Party, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and James Madison (initially), advocated for a strong central government as outlined in the Constitution. They believed a robust federal authority was essential for national stability, economic growth, and international credibility. The Federalists argued that the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first governing document, had proven too weak to address the challenges of the new nation, such as economic instability and defense vulnerabilities.

In contrast, the Anti-Federalists, who included prominent figures like Patrick Henry, George Mason, and Richard Henry Lee, were skeptical of a powerful central government. They feared it would encroach on states' rights and individual liberties, echoing concerns about tyranny that had fueled the American Revolution. Anti-Federalists argued for a more decentralized government, emphasizing the sovereignty of states and the importance of local control. They were particularly critical of the Constitution's lack of a Bill of Rights, which they believed was necessary to protect citizens from potential government overreach. This ideological clash over the role and scope of federal power became the cornerstone of the Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist divide.

The ratification process itself became a battleground for these competing visions. Federalists launched a vigorous campaign to secure approval of the Constitution, culminating in the publication of the *Federalist Papers*, a series of essays written by Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay. These essays systematically defended the Constitution, explaining its provisions and addressing Anti-Federalist concerns. Meanwhile, Anti-Federalists mobilized opposition through speeches, pamphlets, and public meetings, warning of the dangers of centralized authority. The debates were intense and often personal, reflecting the high stakes involved in defining the nation's future governance.

The eventual compromise that led to ratification included the promise of adding a Bill of Rights, which helped sway some Anti-Federalists. However, the divisions persisted, evolving into the first political parties. Federalists, who supported the Constitution and a strong central government, coalesced into the Federalist Party, while Anti-Federalists, who continued to advocate for states' rights and limited federal power, formed the Democratic-Republican Party under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (who shifted his stance). These early party divisions were not merely about policy differences but represented fundamental disagreements about the nature of American democracy and governance.

The Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist debates thus laid the groundwork for the two-party system in the United States. They highlighted the enduring tension between centralized authority and states' rights, a theme that continues to resonate in American politics. The disputes over Constitution ratification were not just about the document itself but about the identity and direction of the young nation. These early divisions underscore the importance of ideological conflict in shaping political institutions and the enduring legacy of the Federalist and Anti-Federalist traditions in American history.

Discover Political Fliers: Top Locations for Campaign Materials

You may want to see also

Hamilton’s Financial Plans: Federalists supported national bank; Anti-Federalists opposed centralized economic policies

The emergence of the first two political parties in the United States—the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists—was deeply rooted in the ideological divide over Alexander Hamilton's financial plans. As the first Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington, Hamilton proposed a series of economic policies aimed at stabilizing and strengthening the fledgling nation's economy. These plans became a lightning rod for debate, ultimately crystallizing the differences between the Federalists, who supported Hamilton's vision, and the Anti-Federalists, who vehemently opposed it.

Hamilton's financial plans were ambitious and centralized, designed to address the economic chaos left in the wake of the Revolutionary War. His proposals included the establishment of a national bank, the assumption of state debts by the federal government, and the implementation of tariffs and excise taxes to generate revenue. The national bank, in particular, was a cornerstone of Hamilton's vision. He argued that a national bank would stabilize the currency, facilitate commerce, and provide a mechanism for the federal government to manage its finances effectively. Federalists, who favored a strong central government, rallied behind Hamilton's ideas, seeing them as essential for the nation's economic and political viability.

Anti-Federalists, however, viewed Hamilton's plans with deep suspicion. Led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, they feared that a national bank and centralized economic policies would concentrate power in the hands of a wealthy elite, undermining the principles of republicanism and states' rights. They argued that such policies would disproportionately benefit urban merchants and financiers at the expense of rural farmers and the common people. The national bank, in particular, was seen as a tool for the federal government to overreach its authority and infringe on the sovereignty of the states. This opposition to centralized economic policies became a defining characteristic of the Anti-Federalist movement.

The debate over Hamilton's financial plans was not merely economic but also philosophical. Federalists believed in a broad interpretation of the Constitution, particularly the "necessary and proper" clause, which they argued granted Congress the authority to establish a national bank and implement other centralized policies. Anti-Federalists, on the other hand, advocated for a strict interpretation of the Constitution, insisting that the federal government should only exercise powers explicitly granted to it. This clash of interpretations laid the groundwork for the enduring tension between federal and state authority in American politics.

The ideological divide over Hamilton's financial plans quickly translated into organized political factions. Federalists, led by Hamilton and supported by figures like John Adams, championed his economic vision and the idea of a strong central government. Anti-Federalists, coalescing around Jefferson and Madison, formed the Democratic-Republican Party, which opposed centralized economic policies and advocated for a more limited federal government. This polarization marked the birth of the first two political parties in the United States, with Hamilton's financial plans serving as the catalyst for their formation.

In summary, Alexander Hamilton's financial plans, particularly his proposal for a national bank, were the focal point of the divide between Federalists and Anti-Federalists. While Federalists supported these centralized economic policies as essential for national stability, Anti-Federalists opposed them as a threat to states' rights and republican values. This disagreement not only shaped the early economic policies of the United States but also laid the foundation for the nation's first political parties, setting the stage for the enduring debate over the role of the federal government in American life.

Unraveling Trump's Political Allegiances: Which Party Did He Truly Support?

You may want to see also

Washington’s Neutrality: First President’s non-partisan stance indirectly fueled party formation

George Washington's presidency, marked by his deliberate neutrality and non-partisan stance, played a pivotal role in the emergence of the first two political parties in the United States. Washington, deeply wary of the divisive nature of political factions, consistently emphasized national unity and avoided aligning himself with any particular group. This neutrality, while intended to foster harmony, inadvertently created a vacuum that allowed competing ideologies to flourish. His cabinet, for instance, became a microcosm of this tension, with figures like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson representing starkly different visions for the nation's future. Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury, advocated for a strong central government and a national banking system, while Jefferson, as Secretary of State, championed states' rights and agrarian interests. Washington's refusal to take sides in these debates allowed these differing philosophies to solidify into distinct political camps.

Washington's Farewell Address in 1796 further underscored his commitment to non-partisanship, as he warned against the dangers of "faction" and the "baneful effects of the spirit of party." However, this very warning highlighted the growing reality of political divisions. By the time of his address, the Federalists, led by Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Jefferson, were already coalescing as organized political parties. Washington's neutrality, rather than preventing party formation, effectively allowed these groups to develop unchecked. His reluctance to endorse either side meant that both factions could claim legitimacy and vie for power without presidential intervention, accelerating the polarization of American politics.

The absence of Washington's direct influence also meant that the ideological debates within his administration spilled over into the public sphere. Hamilton's Federalist policies, such as the creation of a national bank and assumption of state debts, were met with fierce opposition from Jefferson and his supporters. Without Washington's moderating presence, these disagreements escalated into a full-blown partisan struggle. The Federalists, who favored a strong federal government and close ties with Britain, clashed with the Democratic-Republicans, who advocated for limited government and closer relations with France. Washington's neutrality, while principled, failed to stem the tide of party formation, as these competing interests sought to dominate the political landscape.

Ironically, Washington's non-partisan stance became a catalyst for the very partisanship he sought to avoid. His refusal to align with either faction forced political leaders and citizens to choose sides, solidifying the divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. The 1796 presidential election, the first contested election in U.S. history, exemplified this shift, as Federalist John Adams narrowly defeated Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. Washington's departure from office removed the unifying figure who had previously kept factionalism in check, leaving the nation's political system vulnerable to the rise of organized parties.

In conclusion, Washington's neutrality, though rooted in a desire to preserve national unity, indirectly fueled the formation of the first two political parties in the United States. By avoiding partisanship, he created an environment where competing ideologies could flourish without presidential restraint. His cabinet disagreements, Farewell Address, and eventual departure from office all contributed to the rise of Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. While Washington's intentions were noble, his non-partisan stance ultimately proved insufficient to prevent the emergence of a party system that would shape American politics for generations to come.

Understanding the Political Football: Origins, Impact, and Modern Usage Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.55 $65

$26.5 $29.95

Foreign Policy Differences: Federalists pro-British; Democratic-Republicans favored France during global conflicts

The emergence of the first two political parties in the United States—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans—was deeply influenced by their divergent foreign policy stances, particularly their allegiances during global conflicts. The late 18th and early 19th centuries were marked by significant international turmoil, most notably the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars. These events sharply divided American political leaders, shaping the ideological foundations of the two parties. The Federalists, led by figures such as Alexander Hamilton, were staunchly pro-British, viewing Britain as a stable, monarchical ally that shared America’s commercial and strategic interests. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, favored revolutionary France, seeing it as a beacon of republican ideals and a natural ally in the struggle against monarchy and tyranny.

The Federalists’ pro-British stance was rooted in their belief in a strong central government, economic ties with Britain, and a pragmatic approach to foreign policy. They admired Britain’s constitutional monarchy and its role as a global economic powerhouse. During the French Revolution, Federalists were skeptical of its radicalism and violence, fearing that similar unrest could destabilize the young United States. When France and Britain went to war in the 1790s, Federalists advocated for neutrality that leaned toward Britain, culminating in the Jay Treaty of 1794, which normalized trade relations with Britain but angered France. This treaty exemplified the Federalists’ prioritization of economic stability and their willingness to align with Britain to achieve it.

Conversely, the Democratic-Republicans were fervent supporters of France, driven by their ideological commitment to republicanism and their opposition to monarchy. They viewed the French Revolution as a continuation of America’s own struggle for liberty and believed that France’s success was crucial for the global advancement of democratic principles. Jefferson and his followers criticized the Federalists’ pro-British policies, arguing that they betrayed America’s revolutionary heritage. The Democratic-Republicans opposed the Jay Treaty and later protested the Quasi-War with France (1798–1800), which they saw as a Federalist attempt to undermine France and strengthen ties with Britain. Their foreign policy was guided by a moralistic belief in supporting fellow republics, even at the risk of antagonizing a powerful nation like Britain.

The differing allegiances of the two parties were further highlighted during the Napoleonic Wars. Federalists continued to support Britain, viewing Napoleon’s empire as a threat to European stability and American interests. They backed policies like the Embargo Act of 1807, which aimed to protect American shipping from British and French seizures, though they criticized Jefferson’s implementation of it. Democratic-Republicans, while initially sympathetic to France, grew disillusioned with Napoleon’s imperial ambitions but remained wary of Britain’s dominance. Their focus shifted to protecting American sovereignty and expanding westward, as seen in the Louisiana Purchase, rather than aligning closely with either European power.

These foreign policy differences were not merely about international alliances but reflected deeper ideological divides within the United States. Federalists’ pro-British stance aligned with their vision of a strong, centralized government and a market-driven economy, while Democratic-Republicans’ support for France mirrored their emphasis on states’ rights, agrarianism, and republican virtues. The debates over foreign policy during this period solidified the party identities and set the stage for future political conflicts in the United States, demonstrating how global events can shape domestic political divisions.

Has Joe Manchin Switched Political Parties? Exploring His Affiliation Shift

You may want to see also

Jefferson vs. Adams: 1796 election solidified two-party system with distinct ideologies

The 1796 presidential election between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as it solidified the two-party system and highlighted the emerging distinct ideologies that would shape the nation's future. This election was the first contested presidential race in the United States where two clear factions—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans—vied for power. The roots of these parties can be traced back to the debates over the ratification of the Constitution and the policies of George Washington's administration, but it was the 1796 election that crystallized their differences and established a framework for partisan politics.

The Federalists, led by John Adams, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. They believed in a more elitist vision of governance, favoring the interests of merchants, bankers, and the urban elite. Adams, who had served as Washington's vice president, ran on a platform of continuity and stability, emphasizing his experience and commitment to maintaining the Federalist policies that had dominated the 1790s. His supporters saw him as a steady hand capable of navigating the complexities of international relations, particularly in the wake of the French Revolution and the Quasi-War with France.

Thomas Jefferson, on the other hand, emerged as the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party, which championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government. Jefferson's party drew its strength from the South and West, where farmers and small landowners resented Federalist policies they saw as favoring the wealthy and industrial North. Jefferson's vision was rooted in the ideals of the Revolution, emphasizing individual liberty, republican virtue, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. His campaign appealed to those who feared the Federalists were leading the country toward monarchy and aristocracy.

The election itself was a close contest, with Adams winning the presidency and Jefferson becoming vice president under the Electoral College system then in place. This outcome underscored the growing polarization between the two parties and their ideologies. The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans not only disagreed on policy but also represented competing visions of America's identity and future. The 1796 election made it clear that these factions were not merely temporary alliances but enduring political forces with distinct philosophies and constituencies.

The significance of the 1796 election lies in its role as a turning point in American politics. It demonstrated that the young nation's political landscape was no longer dominated by a single, unifying figure like George Washington but was instead characterized by ideological competition. The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans would go on to define the early republic's debates over economic policy, foreign relations, and the balance of power between the federal government and the states. This election laid the groundwork for the two-party system that continues to shape American politics today, with its inherent tensions between centralization and states' rights, and between elite and populist interests. In this way, Jefferson vs. Adams in 1796 was not just a contest for the presidency but a defining moment in the creation of America's partisan political structure.

Understanding Separatism: Political Movements, Independence, and National Identity Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first two political parties in the United States were the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party.

The Federalist Party was led by Alexander Hamilton, while the Democratic-Republican Party was led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

The Federalists favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, whereas the Democratic-Republicans advocated for states' rights, agrarianism, and a more limited federal government.

The first two political parties emerged in the early 1790s, during George Washington's presidency, as debates over the Constitution and the role of the federal government intensified.

The debate over the ratification of the Constitution and the subsequent disputes over Alexander Hamilton's financial policies, such as the national bank, are often cited as catalysts for the formation of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties.