The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause or the Sweeping Clause, is a key constitutional provision that grants Congress the authority to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the federal powers outlined in the Constitution. This clause, found in Article I, Section 8, serves as the basis for a vast array of federal laws, including those establishing the machinery of government and substantive laws such as antidiscrimination and labour laws. While the interpretation of this clause has evolved over time, it provides Congress with significant power to impose laws and regulations on various subjects, including interstate commerce, commerce with Native American tribes, and the encouragement of states to address radioactive waste disposal. However, it's important to note that Congress's powers are not unlimited, and cases such as New York v. U.S. (1992) have highlighted the limitations on congressional power, particularly in compelling states to enact specific policies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Powers | Regulate interstate and foreign commerce |

| Establish post offices and post roads | |

| Punish counterfeiting and piracy | |

| Regulate the use of channels of interstate commerce | |

| Protect the instrumentalities of interstate commerce | |

| Regulate activities that have a substantial relation to interstate commerce | |

| Make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the federal powers granted by the Constitution | |

| Create federal offices | |

| Impose penalties for violation of federal law | |

| Regulate the disposal of radioactive waste generated within states' borders |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Necessary and Proper Clause

> "make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof."

This clause is significant as it gives Congress implied powers in addition to those explicitly stated in the Constitution. This means that Congress has the authority to use all means deemed "necessary and proper" to execute its enumerated powers.

The interpretation of the Necessary and Proper Clause has been a contentious issue since the early days of the US, with Federalists and Anti-Federalists holding differing views. Federalists, including Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, argued that the clause allowed for the execution of powers granted by the Constitution, while Anti-Federalists expressed concern over potential limitless federal power.

The landmark Supreme Court case McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819 further shaped the understanding of the clause. The Court ruled that the clause granted Congress implied powers, such as the power to establish a national bank, as it was reasonably related to Congress's express powers of taxation and spending. This case set a precedent for interpreting the Necessary and Proper Clause as granting Congress broad authority to enact laws necessary for executing its powers.

Philosophers' Influence on the American Constitution

You may want to see also

Interstate commerce regulation

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States, marking the first time an industry, in this case, railroads, came under federal regulation. The Act was passed in response to public anger over unfair railroad rates and the monopolistic practices of railroad companies. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), established by the Act, was tasked with overseeing the conduct of the railroad industry.

The Act set guidelines for how railroads could conduct business, requiring "just and reasonable" rate changes, prohibiting rebates to specific shippers, forbidding long-haul/short-haul discrimination, and banning the pooling of markets or traffic. These provisions aimed to curb monopolies and encourage free competition, which would ultimately benefit the public by ensuring fair pricing and quality services.

The Interstate Commerce Act also had broader implications for federal policy. Before 1887, Congress had applied the Commerce Clause on a limited basis, usually to address barriers that states imposed on interstate trade. The Act demonstrated that Congress could apply the Commerce Clause more broadly to national issues involving commerce across state lines. This shift in federal policy was significant, as it recognised Congress's explicit power to regulate interstate commerce.

The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, grants Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". Courts have generally interpreted this clause broadly, as seen in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), where the Supreme Court affirmed that intrastate activity could be regulated under the Commerce Clause if it is part of a larger interstate commercial scheme.

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, courts took a more conservative approach, with the Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Lopez (1995) that Congress only has the power to regulate the channels of commerce, the instrumentalities of commerce, and actions that substantially affect interstate commerce. This case set a precedent for a more restrained application of the Commerce Clause, ensuring a clear distinction between national and local legislative powers.

The Length of the US Constitution

You may want to see also

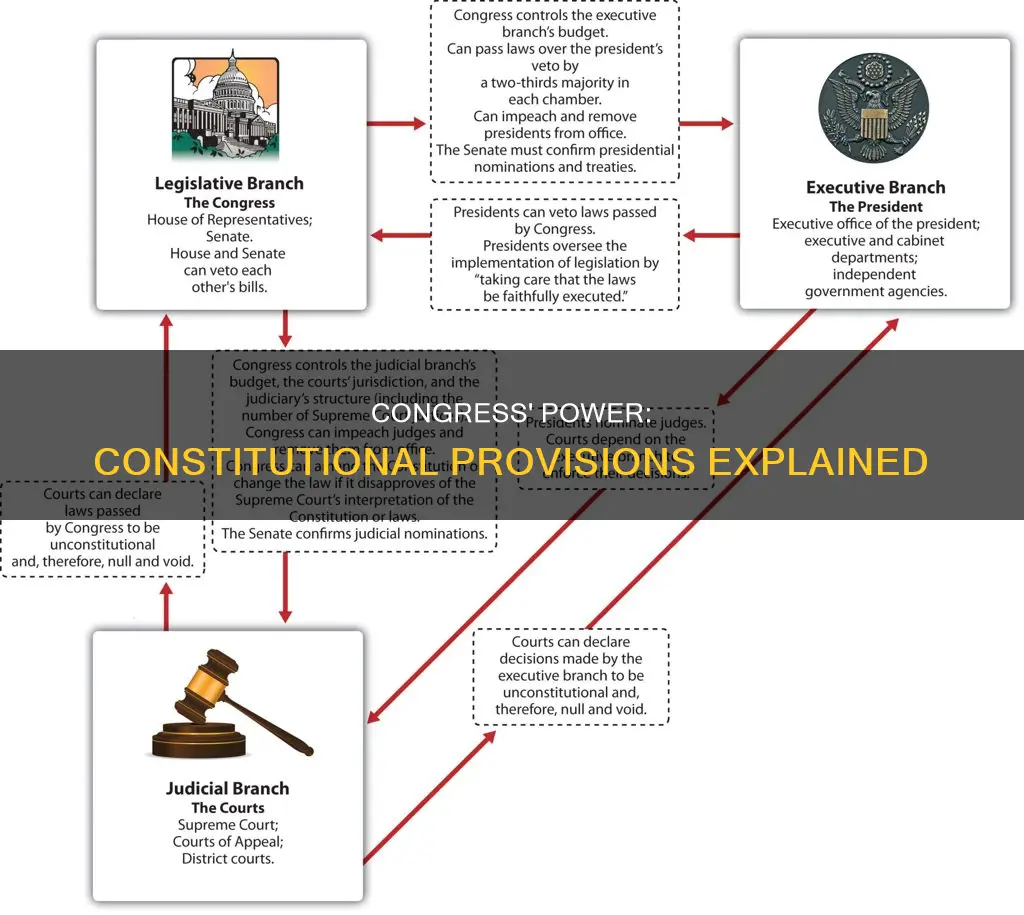

Federal offices and officers

The Constitution grants Congress the power to establish and regulate federal offices and officers, ensuring efficient governance and accountability. Article II, Section 2, Clause 2, known as the "Appointments Clause," empowers the President to nominate, and with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint high-ranking officials such as Supreme Court justices, ambassadors, and heads of federal departments and agencies. This process ensures a collaborative effort between the executive and legislative branches, promoting qualified and vetted appointments.

Congress also holds the authority to establish and organize lower federal offices and officers. Through legislation, Congress creates federal departments, agencies, and courts, defining their structures and responsibilities. This includes determining the roles and duties of federal officers within these entities, ensuring a clear division of labour and promoting specialized expertise.

The legislative branch further oversees the compensation and terms of office for federal officers. Article II, Section 1, Clause 7, the "Compensation Clause," prohibits Congress from increasing or decreasing the salaries of the President, Vice President, and federal judges during their terms of office, ensuring their independence and safeguarding against potential bribery or influence. Congress, however, sets the compensation for other federal officers, allowing for adjustments that reflect economic changes and the market value of specific skills.

In addition to appointment and compensation powers, Congress plays a crucial role in overseeing federal officers' conduct and performance. Through oversight hearings and investigations, Congress ensures that federal officers execute their duties faithfully and in compliance with the law. This accountability measure helps prevent the abuse of power, promotes good governance, and reinforces the system of checks and balances inherent in the separation of powers.

The Constitution's provisions empower Congress to create a competent and accountable federal workforce. This ensures that those entrusted with governing act in the nation's best interests and are ultimately answerable to the people through their elected representatives.

Ilhan Omar's Oath: Constitution or Personal Agenda?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Counterfeiting and piracy

The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) was a proposed United States congressional bill introduced on October 26, 2011, by Representative Lamar Smith. The bill aimed to expand the ability of US law enforcement to combat online copyright infringement and trafficking of counterfeit goods. SOPA included provisions to request court orders to prevent advertising networks and payment facilities from doing business with infringing websites, and to block search engines and internet service providers from linking to these websites. The bill also proposed to expand criminal laws to include unauthorised streaming of copyrighted content, with a maximum penalty of five years in prison.

Supporters of SOPA argued that the bill would protect the intellectual property market, industry, jobs, and revenue. They believed it was necessary to strengthen copyright law enforcement, particularly against foreign-owned and operated websites. The bill received support from various businesses and organisations, as well as industry associations, including the Motion Picture Association of America, the Recording Industry Association of America, and the Entertainment Software Association.

Critics of the bill, however, claimed that it amounted to ""internet censorship" and would impair free speech. There were also concerns about the potential disruption to the technical integrity of the internet. Some critics, like the Center for Democracy and Technology and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, pointed out that the bill's wording was vague and could lead to the blocking of websites based on a single complaint, with the burden of proof resting on the site owner.

In response to the proposed legislation, Wikipedia went black on January 18, 2012, as part of a series of coordinated protests against SOPA and the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA). Over seven million people signed online petitions, expressing concerns about the potential impact on online freedom of speech and the internet. Congress ultimately did not pass the legislation, with lawmakers acknowledging the popular opposition.

In terms of counterfeiting, the United States Constitution grants Congress the power to "provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States". The Supreme Court has interpreted this clause narrowly, focusing specifically on the offence of creating forged coins rather than fraudulently using them in transactions. The Court has also upheld federal statutes penalising the importation, circulation, or possession of counterfeit coins, dies, or depictions of currency.

Power Outages: Emergency or Inconvenience?

You may want to see also

Civil and criminal penalties

The Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause is the source of a range of constitutional rights, including procedural protections, individual rights, and fundamental rights not specifically enumerated elsewhere in the Constitution. The Due Process Clause guarantees citizens the right to notice and a hearing before the termination of entitlements, such as publicly funded medical insurance. Individual rights protected by the Due Process Clause include freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to bear arms, and a variety of criminal procedure protections.

The Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government from imposing unduly harsh penalties on criminal defendants, either as pretrial conditions or as punishment for crimes after conviction. This amendment includes the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause, which is the most important and controversial part of the amendment. The interpretation of this clause has been a subject of debate, with questions arising over what constitutes "cruel and unusual" punishment, whether it prohibits disproportionate punishments, and whether it prohibits the death penalty.

Federal civil rights statutes, such as those within the Crime Control Act of 1994, make it unlawful for governmental authorities or their agents to engage in conduct that deprives individuals of their constitutional rights, privileges, or immunities. These statutes also prohibit any person acting under the colour of law from willfully depriving another person of their rights or subjecting them to different punishments on account of their alien status, colour, or race. Violations of these statutes can result in civil penalties, such as fines, or criminal penalties, including imprisonment or, in more severe cases, the death penalty.

The specific civil and criminal penalties imposed by Congress under its constitutional authority can vary depending on the nature and gravity of the violation. For example, violations of lobbying disclosure requirements can result in civil fines of up to $200,000. On the other hand, violations of certain civil rights statutes can result in criminal penalties, including fines, imprisonment of up to ten years, or even life imprisonment or the death penalty in cases involving kidnapping, aggravated sexual abuse, or murder.

Electricity and the Constitution: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause or Sweeping Clause, is a clause in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. It gives Congress the power to "make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution" the federal powers granted by the Constitution.

The Necessary and Proper Clause gives Congress the power to create federal offices and impose penalties for violations of federal law. It is also the constitutional source of the vast majority of federal laws, including substantive laws such as anti-discrimination laws and labor laws.

The Necessary and Proper Clause does not allow Congress to force people to purchase products or services from others. This was seen in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"), where Congress used the individual mandate to force individuals to purchase health insurance.

The Necessary and Proper Clause grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with states, other nations, and Native American tribes. This includes the power to regulate interstate commerce and prevent states from discriminating against or excessively burdening interstate commerce. However, Congress cannot compel states to enact and enforce federal regulatory programs.