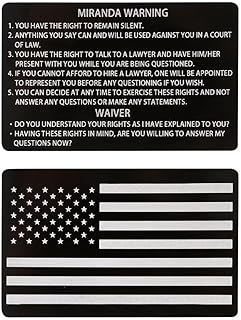

The Miranda warning, or the right to remain silent, is a constitutional amendment that comes from a 1966 United States Supreme Court case, Miranda v. Arizona. The Court ruled that law enforcement must inform individuals of their constitutional rights before an interrogation, or their statements cannot be used as evidence. This ruling was made under the Fifth Amendment, which protects people suspected of crimes from self-incrimination, and the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees the right to an attorney. Miranda motions are, therefore, made under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year of ruling | 1966 |

| Name of case | Miranda v. Arizona |

| Ruling | Police must inform suspects of their constitutional rights before interrogating them, or their statements cannot be used as evidence at trial |

| Constitutional rights | Right to remain silent, right to consult with a lawyer before and during questioning, right against self-incrimination |

| Amendment | Fifth Amendment |

| Exceptions | Harris v. New York (1971), Rhode Island v. Innis (1980), Vega v. Tekoh (2022) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Fifth Amendment and self-incrimination

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects people suspected of crimes from self-incrimination. The Fifth Amendment's self-incrimination clause provides various protections against self-incrimination, including the right of an individual not to serve as a witness in a criminal case in which they are a defendant. This is often referred to as "pleading the Fifth".

The Fifth Amendment also protects criminal defendants from having to testify if they may incriminate themselves through the testimony. In other words, a witness may "plead the Fifth" and not answer if they believe answering the question may be self-incriminatory. The Fifth Amendment privilege against compulsory self-incrimination applies when an individual is called to testify in a legal proceeding.

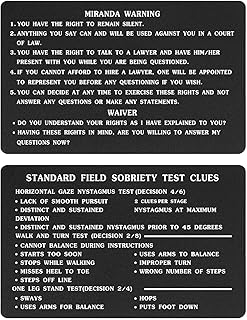

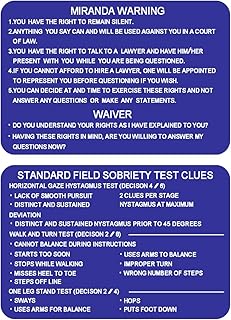

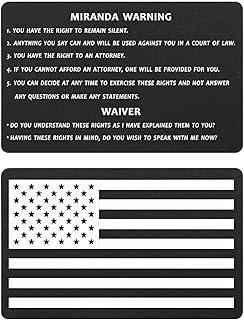

In the landmark case Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Self-Incrimination Clause requires the police to issue a Miranda warning to criminal suspects interrogated while in police custody. This means that law enforcement must make suspects aware of their rights before questioning them. These rights include the right to remain silent, the right to have an attorney present during questioning, and the right to have a government-appointed attorney if the suspect cannot afford one.

If law enforcement fails to honour these safeguards, courts will often suppress any statements made by the suspect as violating the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination, provided that the suspect has not waived their rights. A valid waiver occurs when a suspect has knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily waived their rights. For example, if a suspect invokes their Miranda rights but then behaves in a way that indicates a waiver of those rights, their statements may be admissible in court.

While the Fifth Amendment originally only applied to federal courts, the Supreme Court has partially incorporated it into state-level laws through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Arguments: Commotion or Constitution?

You may want to see also

The Sixth Amendment and right to counsel

The Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury, the right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, the right to confront witnesses, the right to obtain witnesses, and the right to assistance of counsel for the defense. The Sixth Amendment seeks to expand individual rights at the expense of police and prosecutors, shaping the contours of criminal trials in America.

The right to counsel refers to the right of a criminal defendant to have a lawyer assist in their defense, even if they cannot afford to pay for an attorney. The Sixth Amendment gives defendants the right to counsel in federal prosecutions. However, the right to counsel was not applied to state prosecutions for felony offenses until 1963 in Gideon v. Wainwright. The Supreme Court recognized a constitutional right to counsel in this case, but did not require states to provide a remedy or procedure to guarantee that indigent defendants could exercise that right.

The right to counsel is considered the most significant clause in the amendment, as without it, defendants in criminal cases who cannot afford an attorney would find it difficult or even impossible to exercise their fair trial rights. The right to effective counsel typically entails that the attorney engaged in zealous advocacy for the defendant. However, there are exceptions to what attorneys may do for their defendants. For example, in Nix v. Whiteside, the Supreme Court found that an attorney has a duty not to allow a client to give perjured information, and this duty supersedes their duty of zealous advocacy.

The Sixth Amendment right to counsel attaches at or after the initiation of judicial proceedings against the defendant. This typically occurs when a defendant is formally charged, but it can also happen at a preliminary hearing, indictment, or arraignment. In Moran v. Burbine, the Court clarified that an inmate suspected of committing a crime while in prison lacks the right to counsel while in administrative segregation prior to indictment, as this segregation happens before the initiation of adversary judicial proceedings.

Insurance Check Acceptance: Florida's Cashing Conundrum

You may want to see also

Custodial interrogation

In the United States, the law regarding custodial interrogation is primarily governed by the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects individuals from self-incrimination. The landmark case of Miranda v. Arizona in 1966 established the requirement for law enforcement officers to provide "Miranda warnings" prior to custodial interrogation. These warnings inform individuals of their constitutional rights, including the right to remain silent, the right to consult with an attorney, and the right to have an attorney present during questioning. The Supreme Court held that any statements made by an individual during a custodial interrogation without being informed of these rights cannot be used as evidence in a criminal trial.

The Miranda warnings are intended to ensure that individuals are aware of their rights and voluntarily waive them before answering questions. The Supreme Court has clarified that the Miranda warnings are not required in all situations, such as when public safety concerns prompt police questioning or when a suspect initiates further conversation with law enforcement. Additionally, the Court has held that a suspect's subsequent behaviour can constitute a waiver of their Miranda rights, even if they have initially invoked them.

The application of Miranda rights has been a subject of debate and has been refined through subsequent Supreme Court cases. For example, in Rhode Island v. Innis (1980), the Court held that a "spontaneous" statement made by a defendant in custody without Miranda warnings or the presence of an attorney could be admitted as evidence. In Vega v. Tekoh (2022), the Court ruled that police officers could not be sued for failing to administer Miranda warnings, as not every Miranda violation is a deprivation of a constitutional right. These decisions highlight the evolving nature of Miranda rights and their interpretation by the Supreme Court.

Social Media Marketing: Digital Media's Core Strategy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Waiver of rights

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects people suspected of crimes from self-incrimination. In the 1966 case of Miranda v. Arizona, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement must inform individuals of their constitutional rights before they are interrogated while in police custody. These rights include the right to remain silent, the right to an attorney, and the right to appointed counsel if the suspect cannot afford an attorney. The ruling established that the prosecution cannot use statements made by a defendant during police questioning as evidence unless certain procedural safeguards are applied.

The Miranda ruling does not mean that a confession obtained without a prior Miranda warning is automatically inadmissible in court. In some cases, a suspect may waive their Miranda rights, allowing the police to resume questioning. Any waiver must be voluntary and not coerced by law enforcement. A court will closely review the circumstances of the waiver to ensure that the defendant understood their rights and was not manipulated into waiving them. A suspect can waive their rights either expressly or implicitly. For example, a suspect who voluntarily restarts a conversation with police after invoking their right to remain silent may be considered to have implicitly waived their rights.

In some cases, a valid waiver of the right to counsel cannot be established by the fact that the accused responded to police interrogation after being advised of their rights. When an accused has expressed their desire to deal with the police only through counsel, they cannot be subjected to further interrogation until counsel is present, unless they initiate further communication. However, the right to counsel does not apply endlessly once invoked. If an individual leaves police custody and returns or is brought back into custody after a significant amount of time has passed (generally 14 or more days), they must invoke their Miranda rights again, or they will be waived.

Citing a Constitution: MLA Style Guide

You may want to see also

Voluntariness of confessions

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects people suspected of crimes from self-incrimination. In the 1966 case of Miranda v. Arizona, the Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement must warn a person of their constitutional rights before interrogating them. These rights include the right to remain silent, the right to an attorney, and the right to have that attorney present during questioning. If the police fail to administer a Miranda warning, any statements or confessions made by the suspect are presumed to be involuntary and cannot be used as evidence in a trial.

However, a properly warned suspect may waive their Miranda rights and submit to custodial interrogation. A waiver is "the act of intentionally or knowingly relinquishing or abandoning a known right, claim, or privilege." A suspect can waive their rights expressly or implicitly. For example, if a suspect invokes their Miranda rights but then changes their mind and begins talking to the police, their behaviour may constitute a waiver of their rights.

The voluntariness of a confession is a key component of the Miranda decision. Confessions are considered involuntary if they are the product of coercive conduct by the police. Coercive tactics may include depriving someone of food, water, or use of the bathroom, causing physical harm, or threatening harm. Psychological coercion is also a concern in today's criminal justice system. The determination of coercion depends on balancing the circumstances of police pressure against the power of resistance of the suspect. Factors such as age, intelligence, incommunicado detention, denial of requested counsel, and trickery may also indicate the involuntariness of a confession.

In some cases, the police may continue questioning a suspect even after they have invoked their Miranda rights, on the theory that the statement can be used for impeachment if the suspect takes the stand later. However, statements obtained in this manner are typically excluded, and if admitted at trial, will likely be reversed on appeal.

Roberts Rules of Order: Overriding the Constitution?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Miranda warning is a requirement that law enforcement officers in the United States must inform individuals of their constitutional rights before they are interrogated or placed under arrest.

The Miranda rights are the rights that individuals have during police questioning, including the right to remain silent, the right to an attorney, and the right against self-incrimination.

The Miranda warning is based on the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects individuals from self-incrimination.

If the Miranda warning is not given, any statements or confessions made by the individual may be presumed to be involuntary and may be suppressed by the court.

Yes, there have been subsequent court decisions that have granted exceptions to the Miranda warning, such as in the case of Harris v. New York (1971), where confessions obtained in violation of Miranda standards were used to impeach the defendant's testimony.