Mammals are warm-blooded vertebrates with hair or fur, and the ability to produce milk to feed their young. They are the only living members of Synapsida, a clade within the larger Amniota clade, which also includes Sauropsida (reptiles and birds). Mammals have a versatile ability to regulate their body temperatures and internal environment, allowing them to survive in diverse habitats, from cold polar zones to alpine mountain habitats. This internal environment regulation is a key factor in their success, enabling them to exploit various environments and adapt to different conditions. With over 5,000 species, mammals exhibit a wide range of anatomical and physiological characteristics, social structures, and evolutionary adaptations that have contributed to their dominance as a terrestrial animal group.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of species | 5,416 (in 2006) to 6,495 (including 96 recently extinct) |

| Distribution | Worldwide |

| Body type | Quadrupedal, bipedal, adapted for life at sea, in the air, in trees, or underground |

| Size | From less than a gram (bat) to 180 metric tons (blue whale) |

| Habitat | Every major habitat, including cold polar zones and alpine mountain habitats |

| Food habits | Hibernation, aestivation, drinking water, eating succulent plants, or consuming snow and icicles |

| Social structure | Fission-fusion society, solitary |

| Brain | More well-developed than other animal types, with a larger cerebrum in intelligent mammals |

| Body temperature | Ability to regulate body temperature |

| Physical features | Hair or fur, mammary glands, unique jaw joint, lack of nuclei in mature red blood cells |

Explore related products

$29.95 $15.6

What You'll Learn

Ability to regulate body temperature

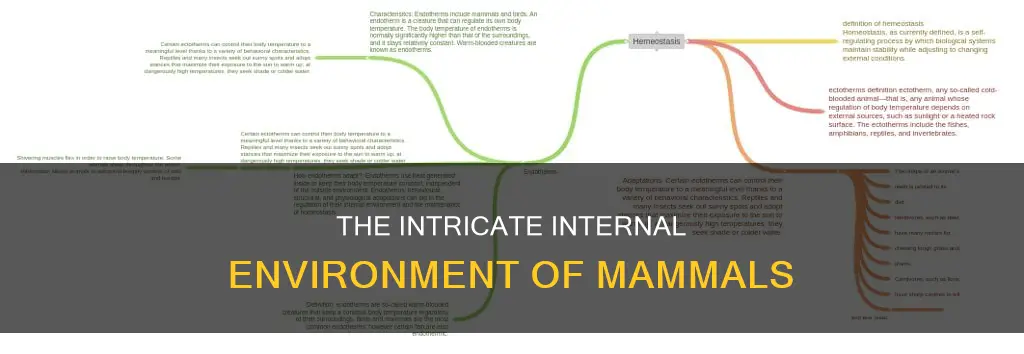

Mammals are warm-blooded animals that can regulate their body temperature and maintain a steady body temperature despite external conditions. This is in contrast to cold-blooded animals, whose body temperature varies according to their surroundings. Thermoregulation is essential for the health of mammals, as it allows bodily processes and organs to function effectively. The human body, for example, maintains a temperature of around 98.6 °F (37 °C). If an individual is unable to regulate their body temperature, they may develop hyperthermia or hypothermia, both of which can be life-threatening.

There are various physical processes that mammals use to regulate their body temperature. Sweating, for instance, helps to lower the body temperature, while shivering raises it. Mammals with fur have a limited ability to sweat and instead rely on panting to increase evaporation across the moist surfaces of the lungs, tongue, and mouth. This is a form of behavioural thermoregulation, which also includes humans putting on a coat in cold weather or seeking shade on hot days. Mammals also have physiological and structural adaptations, such as the ability to raise or lower hair or feathers to minimise heat loss, as well as a feedback system to trigger and control these adaptations.

The preoptic area (POA) of the anterior hypothalamus plays a crucial role in thermoregulation by regulating body temperature in both directions. In rats, neurons in the POA that express the prostaglandin E receptor 3 (EP3) are important for thermoregulation. These neurons provide continuous inhibitory signals using the transmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) to control sympathetic output. Additionally, the body can alter blood flow by narrowing or relaxing blood vessels.

Some mammals also employ strategies such as hibernation or aestivation to conserve energy and regulate body temperature in harsh environments. Larger mammals like bears increase their fat stores before hibernation, while smaller mammals focus on collecting and storing food. During hibernation, the metabolic rate, heart rate, and respiratory rate all decrease, leading to a drop in internal body temperature. Similarly, in hot environments, some mammals aestivate, entering a state of decreased metabolic activity to survive extreme heat or drought.

Georgia's Influence on the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Milk production

The process of milk production occurs in the mammary glands, which are exocrine glands that produce milk in humans and other mammals. The number and positioning of mammary glands vary widely among different mammals. Most mammals develop mammary glands in pairs along two milk lines, with the number of glands roughly approximating the number of young typically birthed at a time. For example, primates have two mammary glands, while pigs have 18. The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates, the udder in ruminants, and the dugs in other animals.

During pregnancy, the ductal systems of the mammary glands undergo rapid proliferation and form alveolar structures within the branches to be used for milk production. After delivery, lactation occurs within the mammary gland, with the secretion of milk by the luminal cells in the alveoli. The contraction of the myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli causes the milk to be ejected through the ducts and into the nipple for the nursing infant.

The synthesis and secretion of milk are fueled by mitochondria, often termed the powerhouses of the cell. The upper part of the cell, closest to the lumen, contains fluid-filled droplets called vesicles, which are composed of different types of proteins. These proteins are assembled into complex structures from simpler chemical building blocks called amino acids within the secretory cells.

The availability of milk allows for a high survival rate of mammalian offspring after birth, providing both sustenance and maternal care. Milk also contains signaling molecules, including nutrients, immunoglobulins, growth factors, and metabolic hormones, which are essential for the growth and development of mammalian young. Lactation also induces a period of infertility in almost all mammals, providing optimal birth spacing for the survival of the offspring.

UK Constitution: A Unique Global Outlier

You may want to see also

Hair or fur

The structure of hair is such that it grows out of pits in the skin called follicles. The base of the hair, embedded in the skin, is called the root, and the part that is visible is the shaft. The root of the hair is located in the dermis, the inner layer of the skin, and the visible part is the epidermis, which is composed of dead cells. The sebaceous gland, located next to the follicle, secretes an oily substance that lubricates and conditions the hair. The arrector pili muscle, also found next to the follicle, causes the hair to stand up when contracted, creating "gooseflesh".

The pelage of most mammals consists of more than one type of hair. The most noticeable hairs are the guard hairs, which overlay the fur and provide protection. These guard hairs can be modified to form defensive spines, bristles, or awns. Underneath the guard hairs is the underfur, which includes wool, fur, and/or velli. The insulation provided by the fur is due to the layer of air trapped within it, acting as an effective insulator. This insulation helps mammals retain body heat, but it can also protect against excessive heat, as seen in diurnal desert animals like camels.

The presence of hair in early mammals is suggested by the small body size and endothermy of their immediate ancestors, indicating a need for insulation. While the exact evolutionary origins of hair are unknown due to the lack of fossilized evidence, it is believed that hair evolved alongside endothermy, or warm-bloodedness, as a means of conserving metabolic energy and maintaining internal body temperature.

Overall, hair or fur plays a crucial role in the internal environment of mammals, providing insulation, protection, and sensory functions that contribute to their survival and adaptability in various habitats.

Napoleon's Constitution: Upholding French Revolutionary Ideals?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$180.29 $219.99

$65.74 $65.9

$5.99 $11.99

Hibernation

During hibernation, mammals rely on stored energy reserves, particularly fats, to sustain their bodily functions. In the period preceding hibernation, larger mammals, such as bears, increase their food intake to build up fat stores, while smaller mammals tend to collect and stash food. This metabolic slowdown allows hibernating mammals to conserve energy.

The extent of the drop in body temperature during hibernation varies between small and large mammals. Smaller hibernating mammals experience extended periods of a hypo-metabolic state called torpor, which significantly decreases their body temperature. Larger mammals, on the other hand, exhibit a less pronounced reduction in body temperature during hibernation, with their temperature remaining relatively consistent. For example, the internal temperatures of hibernating Arctic ground squirrels can drop to −2.9 °C (26.8 °F), while the head and neck remain above 0 °C (32 °F).

The role of myosin, a type of motor protein involved in muscle contraction, has been studied in the context of hibernation. Research suggests that myosin plays a role in non-shivering thermogenesis during hibernation, where heat is produced independently of the muscle activity of shivering. This may help prevent significant muscular atrophy in hibernating mammals.

Alien and Sedition Act: Unconstitutional Violation?

You may want to see also

Social structures

Sociality in mammals refers to the degree to which individuals in a population associate and cooperate in social groups. Sociality is a response to evolutionary pressures, where cooperation and group living increase the chances of survival and successful reproduction.

Mammalian societies are complex and vary within and among species. They are influenced by a range of internal and external factors, including social, genetic, developmental, and ecological constraints. Social structures in mammals can be influenced by the need to defend territories, detect and avoid predators, and compete with neighbouring groups. For example, female mammals often form stable groups with matrilineal relatives, cooperating to defend feeding or breeding territories and rear young. In some species, such as mole-rats, sociality is influenced by the need to maintain extensive tunnel systems, while in larger carnivores like canids, sociality improves hunting success. Sociality can also be influenced by the need to protect and transport dependent offspring, as seen in callitrichids.

The social structure of a species can also influence its mating system. Monogamous mating has been identified as a condition for the evolution of cooperative breeding in some mammals, while polygynous breeding systems are common among mammals, leading to intense competition between males. In some species, one dominant female monopolizes reproduction in each group, and her offspring are reared by other group members.

The size of a social group can vary depending on the species and its specific constraints and environmental factors. For example, the group size of black and white colobus monkeys remains relatively stable in different habitats due to their limited digestive and detoxification abilities. In contrast, the Kibale omnivores exhibit an inverse relationship between body and group size.

Social mammals also tend to exhibit higher cognitive abilities. Social predators like lions and spotted hyenas have been found to be better problem solvers than non-social predators like leopards and tigers. This suggests that sociality and cooperation can enhance a species' ability to adapt and respond to their environment.

Reciprocity Treaty: Forcing the Bayonet Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mammals are warm-blooded vertebrates with hair or fur on their bodies. They feed their young with milk produced by mammary glands and have a more well-developed brain than other types of animals.

Mammals can be categorised into three large orders based on species: Rodentia (mice, rats, etc.), Chiroptera (bats), and Eulipotyphla (shrews, moles, etc.). The next three biggest orders are primates, Cetartiodactyla, and Carnivora.

The internal environment of a mammal is maintained by the ability to regulate body temperature, both in excessive heat and aridity and in severe cold. This is achieved through processes like hibernation, where metabolism slows down, and aestivation, where mammals in hot environments reduce their activity during drought or extreme heat.

Mammals have successfully adapted to a wide range of environments, from cold polar zones to alpine mountain habitats. They have diverse patterns of lactation, social structures, and hunting strategies that allow them to survive in various ecosystems.

Mammals possess unique features such as specialised tooth structures and a unique jaw joint. They also have a malleus, incus, and stapes in the ear. Some mammals, like primates, have larger cerebrums relative to the rest of their brains.