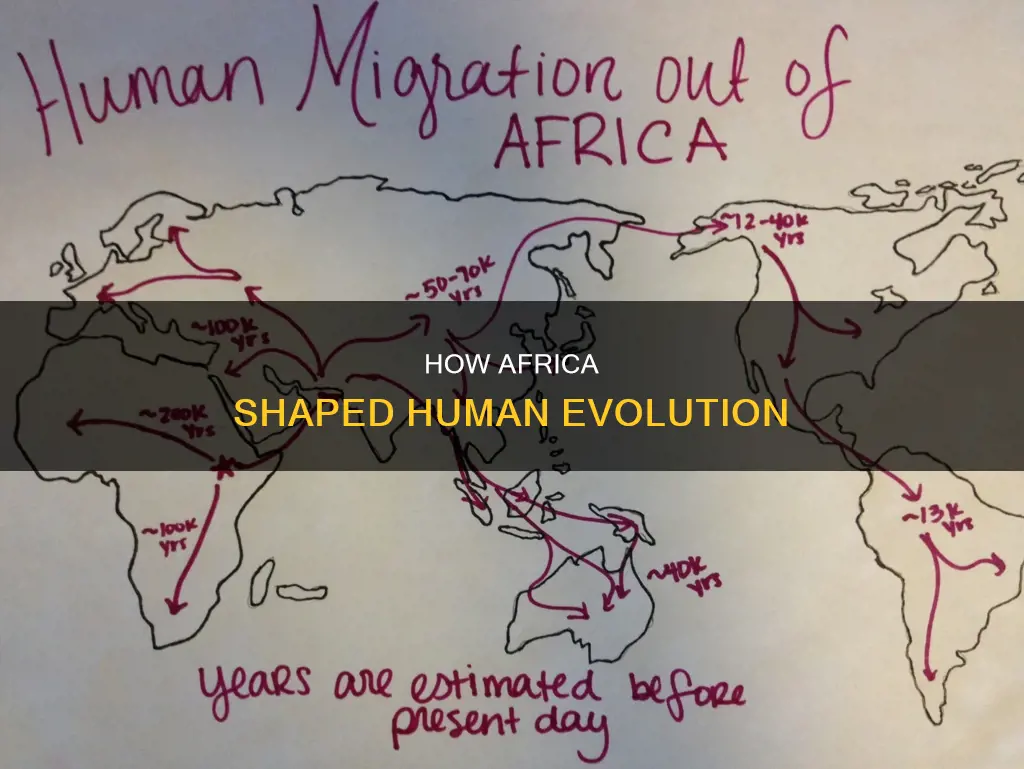

The 'Out of Africa' hypothesis, also known as the 'Out of Africa' model or theory, proposes that the Homo genus migrated out of Africa to populate the rest of the world. This hypothesis has been supported by genetic, fossil, and archaeological evidence. Genetic studies have shown that genetic diversity decreases with increasing migratory distance from East Africa, and that modern humans share a common ancestry with mitochondrial DNA tracing back to Africa. Fossil evidence also supports the hypothesis, as fossils phenotypically resembling modern humans are found in Africa earlier than anywhere else. Additionally, archaeological evidence, such as skeletal and tool remains, provides insights into early human migration patterns. However, there are still debates and inconsistencies regarding the specific timings, extent of interbreeding, and replacement or coexistence with other hominin populations.

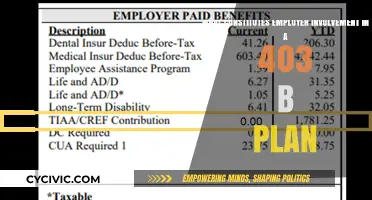

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin of modern humans | East Africa |

| Date of origin | 150,000 years ago |

| Migration | Began 70,000-90,000 BP |

| Migration path | Through South Asia to Australasia and Eurasia |

| Genetic diversity | Decreases with distance from Africa |

| Genetic loci | Some roots outside of Africa |

| Gene-flow | Between archaic humans in different regions |

| Homo erectus | Settled in Europe and Asia |

| Neanderthals | Replaced by Homo sapiens |

| Homo sapiens | No interbreeding with Neanderthals |

| Mitochondrial DNA | Greater diversity in Africa |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mitochondrial DNA analysis

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis has been used to support the Out of Africa model, which proposes that modern humans originated in Africa and subsequently migrated to populate the rest of the world. This analysis involves examining the genetic material found in the mitochondria of cells, which is inherited maternally, to trace ancient population migrations and understand the evolutionary relationships between different groups.

The first genetic evidence for the Out of Africa model came from studies of mtDNA phylogenetic trees, which identified Africa as the source of the human mtDNA gene pool. All mtDNA haplogroups outside of Africa can be traced back to either the M or N haplogroups, which are believed to have originated on the African continent. This suggests that modern humans carrying these haplogroups migrated out of Africa and replaced the indigenous populations they encountered.

Additionally, mitochondrial DNA analysis has revealed that genetic diversity decreases with increasing geographic distance from East or South Africa. This finding is consistent with the Out of Africa model, which predicts that as humans migrated away from Africa, they carried only a portion of the genetic diversity of their parental colonies, resulting in decreasing genetic diversity over time.

Further support for the Out of Africa model comes from the discovery that mtDNA variants defining the most common African genetic background, the L haplogroup, exhibit distinct overall mtDNA gene expression patterns. These expression patterns are independent of mtDNA copy numbers and are associated with an altered tendency to develop complex traits that conferred adaptive advantages during human evolution.

While mtDNA analysis has provided valuable insights into the Out of Africa model, it is important to note that the model has evolved to incorporate new genetic and archaeological findings. For example, recent genetic research suggests that the evolution of modern humans involved contributions from multiple archaic populations, rather than a single origin in Africa. Additionally, the concept of "Mitochondrial Eve," which is based on mtDNA analysis, has been refined over time and is now understood to refer to the most recent common matrilineal ancestor, not the only living female of her time.

Christianity and the US Constitution: Official Religion?

You may want to see also

Genetic diversity decreases with distance from Africa

The "Out of Africa" theory, also known as the "Out of Africa" model or hypothesis, is a well-established idea in anthropology that suggests that modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved to their modern form in Africa around 150,000 years ago and then began to populate the rest of the world through migration. This theory is supported by archaeological data, mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal DNA analysis, and genome-wide genotyping and sequencing techniques.

Genetic diversity is highest in Africa, and it decreases with distance from the continent. This pattern is known as the serial founder effect and is consistent with the "Out of Africa" model. As humans migrated away from Africa in successive waves, they carried only a portion of their parental colonies' genetic diversity, leading to a reduction in genetic variation in populations farther from Africa. This phenomenon has been observed in studies of autosomal genetic variation, which show that genetic distance between populations increases with geographic distance from East Africa.

Several studies in population genetics have provided empirical evidence for the correlation between migratory distance from Africa and genetic diversity. For example, Prugnolle et al. (2005), Ramachandran et al. (2005), and Wang et al. (2007) found results that supported the prediction of decreasing genetic diversity with increasing distance from Africa. Additionally, multilocus studies of genome-wide data have shown a linear decrease in heterozygosity and an increase in linkage disequilibrium with distance from East or South Africa.

The higher genetic diversity in African populations is attributed to the longer time they have had to accumulate genetic variations. Africa is considered the starting point of human evolution, and African populations are about four times as "old" as European populations. This extended period allowed for more genetic mutations and adaptations to diverse environments within Africa.

However, it is important to note that the "Out of Africa" model has been challenged by recent genetic research. While Africa remains crucial in all theories of modern human origins, evidence suggests that the evolution of modern humans involved contributions from multiple archaic populations, including those outside of Africa. This challenges the idea of a single origin for modern humans and indicates that gene flow occurred between archaic humans in different regions, contradicting the concept of separate species.

The Delegates' Plans: Two Distinct Paths for the Nation's Future

You may want to see also

Fossil and genetic data

Genetic evidence plays a pivotal role in substantiating the "Out of Africa" model. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis has been particularly informative. Studies of mtDNA phylogenetic trees have identified Africa as the source of the human mtDNA gene pool. Specifically, all mtDNA haplogroups outside of Africa can be traced back to either the M or N haplogroups, which originated on the African continent. This genetic diversity is consistent with the idea that a small subpopulation of Africans migrated and settled in other regions.

Furthermore, multilocus studies of genome-wide data have revealed that genetic diversity decreases with increasing geographic distance from East or South Africa. This pattern, known as serial-founder effect originati, is indicative of successive migrations from Africa, with each new colony carrying only a portion of the genetic diversity of their parental colonies. This finding aligns with the "Out of Africa" model and provides compelling genetic evidence for it.

In addition to genetic evidence, fossil records also contribute to our understanding of human evolution and the "Out of Africa" hypothesis. The discovery of fossils phenotypically resembling recent humans in Africa earlier than anywhere else supports the idea that modern humans originated on the African continent. This evidence, combined with genetic data, suggests that gene flow occurred between modern and archaic populations, as well as between geographic groups of modern humans after their emergence.

While the "Out of Africa" hypothesis is widely accepted, it is important to acknowledge that human evolution is a complex process. Recent genetic research suggests that modern humans likely received genetic contributions from multiple archaic populations, challenging the idea of a single, recent common ancestor. Additionally, inconsistencies in the fossil and archaeological records, such as those found in Australia, have led to debates about possible interbreeding with local Homo erectus populations or secondary migrations from Africa.

Grounds for Annulment in the Catholic Church

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Human evolution in Africa

One of the key pieces of evidence for the "Out of Africa" theory is genetic diversity. Studies have shown that genetic diversity decreases with increasing migratory distance from East or South Africa. This pattern is consistent with the prediction that as subgroups left Africa and established new colonies, they carried only a portion of the genetic diversity of their parental colonies. By analysing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and Y-chromosomal DNA, researchers have traced the evolutionary history of modern humans back to Africa.

Additionally, the "Out of Africa" theory addresses the existence of inconsistent evidence, particularly in Australia, where skeletal and tool remains differ significantly from those found along the "coastal expressway" route taken by early settlers. Some scholars attributed these discrepancies to interbreeding with the local Homo erectus population or a secondary migration from Africa. However, recent genetic research has found no evidence of genetic inheritance from Homo erectus, supporting the idea of a single, common origin for modern-day humans in Africa.

Furthermore, the "Out of Africa" theory considers the evolutionary processes that occurred beyond 100,000 years ago, including the development of bipedalism. The model also highlights the role of Africa as the "engine room" for the evolution of the Homo genus, with fossils phenotypically resembling recent humans found in Africa earlier than anywhere else. This supports the idea that Africa was the centre of Pleistocene human evolution and made the largest regional contribution to the gene pool of modern humans.

While the "Out of Africa" theory provides a compelling explanation for human evolution in Africa, it is important to acknowledge the existence of alternative models, such as the multiregional model and the candelabra model. These models propose different scenarios for the evolution and migration of hominins, highlighting the complexities and ongoing debates in understanding human evolutionary history.

Constitutional Initiative: Democracy in Action

You may want to see also

Neanderthal extinction

Another theory posits that the extinction of Neanderthals was caused by their displacement by modern humans. DNA evidence indicates that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals had contact and interbred as early as 120,000 to 100,000 years ago. However, the two species competed for resources, and as modern humans expanded deeper into Eurasia, they may have driven Neanderthals to extinction. This theory is supported by archaeological evidence, which shows that Neanderthals displaced modern humans in the Near East around 100,000 years ago until about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago. The idea of violent conflict between the two groups has also been proposed as a contributing factor in Neanderthal extinction.

Disease transmission may also have played a significant role in the extinction of Neanderthals. Mathematical models suggest that even small differences in disease burden between Neanderthals and modern humans would have grown over time, eventually giving Homo sapiens an advantage. As modern humans expanded into Eurasia, they would have encountered Neanderthal populations that lacked protective immune genes, making them more susceptible to diseases brought by the former. This scenario is similar to what happened when Europeans arrived in the Americas and decimated indigenous populations with their diseases.

Additionally, some researchers argue that Neanderthals did not become extinct but were instead assimilated into the modern human gene pool. Recent research on Neanderthal nuclear DNA provides evidence for limited admixture, suggesting that interbreeding occurred during the early dispersal of modern humans out of Africa. However, the fossil record is ambiguous, and analysis of mitochondrial DNA has not shown clear evidence of interbreeding.

The extinction of Neanderthals may also be attributed to a combination of factors, including environmental deterioration, competition with modern humans, and the unique physical characteristics of Neanderthals. For example, the wider pelvis of Neanderthals compared to modern humans may have made certain physical activities more challenging, giving Homo sapiens an advantage in terms of walking and running ability.

The Magna Carta's Constitutional Principles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Out of Africa model, also known as the Out of Africa hypothesis, is the theory that the Homo genus migrated out of Africa to populate the rest of the world.

The first genetic evidence for the Out of Africa model was provided by the study of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) phylogenetic trees, which identified Africa as the source of human mtDNA gene pools. Further evidence comes from the fact that there is greater genetic diversity in Africa than outside of it, which is consistent with the model that a small subpopulation of Africans moved out of Africa and populated the rest of the world.

The fossil record shows that fossils phenotypically resembling modern humans are found in Africa earlier than anywhere else, suggesting that modern humans originated in Africa.

One challenge to the Out of Africa model is the existence of inconsistent evidence in Australia, where the skeletal and tool remains that have been found differ significantly from those found elsewhere. This could be explained by a secondary migration from Africa or interbreeding with the local Homo erectus population, but recent research has found no evidence of genetic inheritance from Homo erectus.