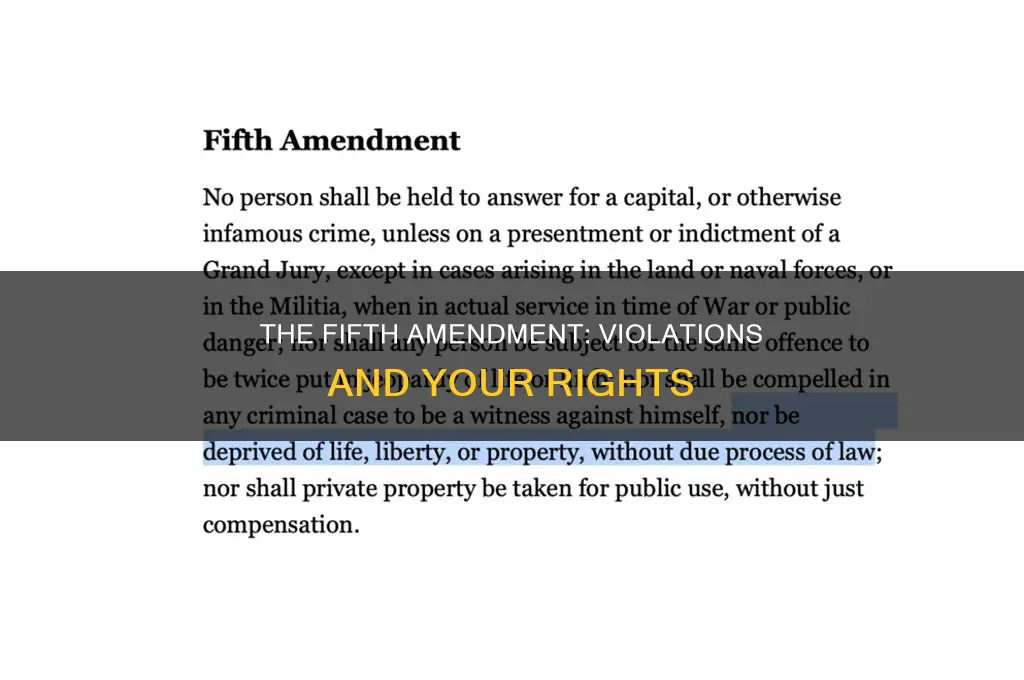

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution creates several rights that limit governmental powers, particularly in criminal procedures. Violations of the Fifth Amendment include denying citizens the right to a grand jury, allowing double jeopardy, and forcing self-incrimination. The amendment also protects citizens from being deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process and requires just compensation for the government's seizure of private property. Lower courts have given conflicting decisions on whether compelled disclosure of computer passwords violates the Fifth Amendment. The Supreme Court has extended most Fifth Amendment rights to state and local levels, except for the right to indictment by a grand jury.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Failure to honour safeguards | Courts may suppress statements by suspects |

| Forced disclosure of computer passwords | Lower courts have given conflicting decisions |

| Suspect waives rights knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily | Spontaneous statements can be used against the suspect |

| Right to indictment by a grand jury | Does not apply to the state level |

| Double jeopardy | Defendants cannot be tried twice for the same offence |

| Self-incrimination | Suspects cannot be compelled to be a witness against themselves |

| Due process | Citizens receive fundamentally fair, orderly, and just judicial proceedings |

| Seizure of private property | Citizens must receive market value compensation |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

$22.49 $35

What You'll Learn

Forced disclosure of computer passwords

The Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution creates several constitutional rights, limiting the powers of the government with respect to criminal procedures. One of these rights is the protection against self-incrimination.

The question of whether forced disclosure of computer passwords violates the Fifth Amendment has been the subject of much debate and conflicting decisions in lower courts. The Supreme Court has not yet provided a definitive ruling on this issue.

Some courts have held that requiring an individual to disclose a password is a form of testimonial act, which could be protected by the Fifth Amendment. This is because the password itself is considered "pure testimony", and compelling its disclosure would be akin to forcing an individual to incriminate themselves. In the case of In re Boucher (2009), the US District Court of Vermont ruled that the Fifth Amendment might protect a defendant from having to reveal an encryption password if doing so could be deemed a self-incriminating "act".

However, other courts have distinguished between compelled disclosure and compelled entry. In these cases, the courts have argued that compelled entry, where an individual is required to enter a password without disclosing it, does not trigger the same Fifth Amendment protections as compelled disclosure. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, for example, held that the only implicit testimony at issue in compelled entry is whether the defendant knows the password.

The treatment of biometric decryption, such as facial recognition or thumbprint reading, has also added to the complexity of this issue. The Utah Supreme Court has ruled that the foregone conclusion doctrine, which states that the government must prove it already knows the evidence exists and is within the suspect's possession, does not apply in compelled decryption cases.

The lack of a clear and consistent ruling on this issue has resulted in varying Fifth Amendment rights depending on the jurisdiction and the specific circumstances of each case.

Amending the Constitution: What's Next?

You may want to see also

Self-incrimination

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution creates several constitutional rights, limiting governmental powers with a focus on criminal procedures. One of these rights is the protection against self-incrimination. This means that no person can be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against themselves.

The Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination is often invoked when a suspect is in custody and being interrogated by law enforcement. If a suspect has not been properly informed of their Miranda rights, which include the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney, any statements they make may be suppressed by a court as a violation of the Fifth Amendment.

The right against self-incrimination also applies to the production of certain types of evidence. For example, in the case of In re Boucher (2009), the US District Court of Vermont ruled that the Fifth Amendment might protect a defendant from having to reveal an encryption password if doing so could be deemed a self-incriminating "act". However, lower courts have given conflicting decisions on this issue, and it is still evolving.

The Fifth Amendment right does not apply to voluntarily prepared business papers or other documents because the element of compulsion is lacking in these cases. Additionally, if a suspect makes a spontaneous statement while in custody, even before being made aware of their Miranda rights, that statement can be used against them as long as it was not prompted by police interrogation.

Amendment Impact: 18th Amendment's Constitutional Changes

You may want to see also

Double jeopardy

The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution provides protection against being prosecuted twice for the same crime. This means that a defendant has the right to be tried only once in federal court for the same offence. The Clause applies to both the federal and state governments, and covers criminal punishment, although not all sanctions.

The Double Jeopardy Clause does not attach in a grand jury proceeding, or bar a grand jury from returning an indictment when a prior grand jury has refused to do so. However, a person who is convicted of one set of charges cannot generally be tried on additional charges related to the crime unless said additional charges cover new facts against which the person in question has not yet been acquitted or convicted. This is known as the Blockburger test.

In certain cases, civil penalties may qualify if they are punitive. For example, in United States v. One Assortment of 89 Firearms (1984), the Supreme Court held that the prohibition on double jeopardy extends to civil sanctions that are punitive in nature. In United States v. Halper (1989), a civil sanction under the False Claims Act was deemed to constitute punishment if it overwhelmingly compensated the government for its loss and could only be explained as serving a retributive or deterrent purpose.

The Double Jeopardy Clause applies in juvenile court proceedings that are formally civil. For example, in Breed v. Jones (1975), the Supreme Court decided that double jeopardy applies to an individual tried as a juvenile and later tried as an adult.

The Constitution, Supreme Court, and Amendments: United States' Foundation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Due process

The Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution outlines several constitutional rights that limit governmental powers, particularly in criminal procedures. The amendment includes the Due Process Clause, which requires "due process of law" in any proceeding that could result in a citizen being deprived of "life, liberty, or property".

The Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause has been extended to the state and local levels through the Fourteenth Amendment. While the right to indictment by a grand jury has not been incorporated at the state level, other rights have, including the right against double jeopardy, the right against self-incrimination, and the protection against arbitrary taking of private property without due compensation.

Courts have interpreted the Due Process Clause to mean that any evidence obtained in violation of the Fifth Amendment cannot be used in court. For example, if a suspect has not been made aware of their Miranda rights, which include the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney, any statements made may be suppressed as a violation of the Fifth Amendment.

The Due Process Clause also protects citizens from being compelled to provide encryption passwords or access to encrypted devices, as this could be deemed a self-incriminating "act". However, there have been conflicting decisions on this issue, with some courts ruling that providing an encrypted device or password does not constitute self-incrimination if there is already sufficient evidence to tie the encrypted data to the defendant.

Amendments: Who Can Propose Constitutional Changes?

You may want to see also

Seizure of private property

The Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states that "no person shall be [...] deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation". This means that the government cannot seize private property without providing market-value compensation.

The Fifth Amendment's protection against the arbitrary seizure of private property without due compensation has been incorporated into the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. While the Fifth Amendment initially only applied to federal courts, the U.S. Supreme Court has extended it to the states. The Due Process Clause ensures that a party will receive a fundamentally fair, orderly, and just judicial proceeding.

The federal government has a constitutional right to "take" private property for public use, but the Fifth Amendment's Just Compensation Clause requires that the government provide just compensation, interpreted as market value. This is to ensure that the seizure of private property is not conducted arbitrarily or without proper process.

In 2005, in Kelo v. City of New London, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a city could constitutionally seize private property for private commercial development if it would economically benefit an area that was "sufficiently distressed to justify a program of economic rejuvenation". This decision was controversial, and some scholars argued that it eliminated the distinction between private and public use of property, favouring those with greater influence and power.

The Fourth Amendment also protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures, ensuring that warrants are issued only upon probable cause and describe the place to be searched and the items to be seized. While the Fourth and Fifth Amendments often overlap, the Fifth Amendment specifically safeguards against self-incrimination and double jeopardy, providing distinct constitutional rights.

Amending Freedom: Republic's Evolution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Fifth Amendment is part of the United States Constitution, which outlines constitutional rights and limits on governmental powers, particularly in criminal procedures.

The Fifth Amendment guarantees the right to a grand jury, forbids double jeopardy, and protects against self-incrimination. It also ensures citizens receive due process of law and requires the government to compensate citizens for the seizure of private property for public use.

The Fifth Amendment requires that most felonies be tried only upon indictment by a grand jury. However, this does not apply to the state level. A grand jury is composed of a jury of peers and operates in closed deliberation proceedings.

Courts have ruled that law enforcement cannot compel a suspect to provide incriminating evidence against themselves. This includes forced disclosure of computer passwords, depending on the specific circumstances. Spontaneous statements made by a suspect prior to being made aware of their Miranda rights may also be used, provided they were not prompted by police interrogation.

Due process essentially guarantees a fundamentally fair, orderly, and just judicial proceeding. This means the government must respect all rights, guarantees, and protections afforded by the Constitution and applicable statutes before depriving any person of life, liberty, or property.