Commercial speech is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment, though it does not receive the same level of free speech protection as non-commercial speech. The term commercial speech was first introduced by the Supreme Court in 1942, which ruled that commercial speech in public is not protected under the First Amendment. However, in the 1970s, the Court's treatment of commercial speech began to change, and it gradually recognised that this type of speech deserved some First Amendment protection. Since then, the Supreme Court has heard several cases that have further defined and expanded the protections afforded to commercial speech, such as Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), which held that advertisements are acts of speech that qualify for First Amendment protection, and 44 Liquormart v. Rhode Island (1996), which struck down a state law banning the advertising of alcohol prices.

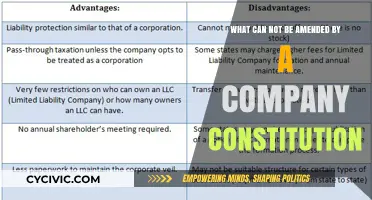

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Commercial speech protection under the First Amendment | Commercial speech is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment, but it does not receive as much free speech protection as non-commercial speech. |

| Commercial speech defined | Commercial speech includes all forms of marketing, such as advertising, labelling, and price information. |

| Commercial speech and monetary transactions | Speech does not lose its protection under the First Amendment simply because money is transacted through it. |

| Commercial speech and regulation | Commercial speech can be regulated by the government if it is false or misleading. |

| Commercial speech and the Central Hudson test | The Central Hudson test is used to determine how far the regulation of commercial speech can go before it violates the First Amendment. |

| Commercial speech and compelled speech | Commercial speech can be compelled by the state without violating the advertiser's First Amendment rights, as long as it includes factual information for consumer awareness. |

| Commercial speech and public health | Companies have a constitutional right to market products associated with public health harms, such as alcohol, tobacco, and food. |

| Commercial speech in Europe | Commercial speech is protected under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Commercial speech includes marketing, advertising, labelling, and price information

- Commercial speech is protected under the First Amendment, but less so than political speech

- Commercial speech can be restricted and compelled

- The Central Hudson test determines how far regulation of commercial speech can go

- Commercial speech is entitled to less protection if it is false or misleading

Commercial speech includes marketing, advertising, labelling, and price information

Commercial speech is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment, but it does not receive the same level of free speech protection as non-commercial speech, such as political speech. Commercial speech includes all forms of marketing, advertising, labelling, and price information.

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in defining and extending First Amendment protection to commercial speech. In the 1975 case of Bigelow v. Virginia, the Court ruled that an individual had the right to advertise abortion services in a state where the procedure was illegal. Justice Harry Blackmun asserted that the First Amendment protects not only the speaker's right to speak but also the listener's right to receive information. This case marked a shift in the Court's treatment of commercial speech, recognising it as deserving of First Amendment protection.

The following year, in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976), the Supreme Court explicitly extended First Amendment protection to commercial speech. The Court struck down a state law prohibiting pharmacies from advertising drug prices, further solidifying the inclusion of price information under commercial speech.

The Central Hudson test, established in the 1980 case of Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission, provides a framework for determining if government restrictions on commercial speech are constitutional. This test considers whether the expression is protected by the First Amendment, the government's asserted interest in restricting commercial speech, the direct advancement of that interest, and the extent of the restriction.

The inclusion of marketing, advertising, labelling, and price information under commercial speech has been further reinforced through various Supreme Court cases. For example, in Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co. (1995), the Court invalidated a federal ban on revealing alcohol content on malt beverage labels. Additionally, in 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island (1996), the Court struck down a state law banning the advertising of alcohol prices, reinforcing the protection of price information under commercial speech.

While commercial speech, including marketing, advertising, labelling, and price information, is protected, it is not immune from government regulation. The Court has noted that commercial speech can be regulated if it is false, misleading, or deceptive. The Zauderer standard, established in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of the Supreme Court of Ohio (1985), allows the government to mandate the inclusion of factual and uncontroversial information in commercial speech to prevent consumer confusion or promote consumer awareness.

Extending Term Limits: Overturning Constitutional Amendments

You may want to see also

Commercial speech is protected under the First Amendment, but less so than political speech

Commercial speech, which includes all forms of marketing, such as advertising, labelling, and price information, is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment. However, it does not receive as much free speech protection as non-commercial speech, such as political speech.

The transformation in the Court's treatment of commercial speech began in the 1970s, when it started to recognise commercial speech as deserving of some First Amendment protection. In Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), the Supreme Court ruled that an individual had the right to advertise abortion services in a state where the procedure was illegal. Justice Harry A. Blackmun observed that "the existence of commercial activity, in itself, is no justification for narrowing the protection of expression secured by the First Amendment."

The Supreme Court extended First Amendment protection to commercial speech in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976), striking down a state law prohibiting pharmacies from advertising drug prices. Justice Blackmun asserted that the First Amendment includes not only the right to speak but also the right to receive information. This case overturned the precedent set in Valentine v. Chrestensen (1942), where the Supreme Court ruled that commercial speech in public is not protected under the First Amendment.

While commercial speech is protected, it is not immune from government regulation. Commercial speech is subject to greater regulation than political speech and can be regulated if it is false or misleading. The Court has developed the Central Hudson test to determine the protection for commercial speech. This test evaluates whether the expression is protected by the First Amendment, the government's interest in restricting commercial speech, and the extent of the restriction. If the speech is fraudulent or illegal, the government can freely regulate it without First Amendment constraints.

Royal Assent: Australia's Unique Constitutional Amendment Process

You may want to see also

Commercial speech can be restricted and compelled

Commercial speech, which includes commercial advertising, promises, and solicitations, is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment. However, it does not receive the same level of free speech protection as non-commercial speech, such as political speech. This is because commercial speech is viewed as more objective and subject to determination of its truth content. As a result, it can be regulated if found to be false or misleading.

The transformation in the treatment of commercial speech by the Court began in the 1970s, with the Supreme Court gradually recognising it as deserving of some First Amendment protection. In Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), the Supreme Court ruled that an individual had the right to advertise abortion services in New York to residents of Virginia, where the procedure was illegal at the time. Justice Harry A. Blackmun observed:

> 'The existence of commercial activity, in itself, is no justification for narrowing the protection of expression secured by the First Amendment.'

Shortly after, in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976), the Supreme Court extended First Amendment free speech protection to commercial speech, striking down a state law that prohibited pharmacies from advertising drug prices.

Despite this protection, commercial speech can be restricted. For example, in 1996, the Supreme Court used a four-pronged test to consider the government's interest in limiting price information in alcohol advertisements and ultimately struck down the law. This demonstrates that while commercial speech is protected, it can be restricted if it is found to be in the public interest to do so.

In addition to being restricted, commercial speech can also be compelled, as held by the Supreme Court in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel. The Court ruled that a state may compel commercial speech without violating the advertiser's First Amendment rights.

Amendments: A Living Constitution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Central Hudson test determines how far regulation of commercial speech can go

The Central Hudson test is a form of intermediate scrutiny used to determine how far the regulation of commercial speech can go before infringing on First Amendment rights. It was developed by the Supreme Court in 1980 in the case Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission of New York, which clarified the First Amendment protection of commercial speech.

The test consists of four parts:

- The threshold prong asks whether the speech concerns lawful activity and is not misleading or fraudulent. If the speech is illegal or deceptive, the government can regulate it without First Amendment constraints.

- If the speech is lawful and non-misleading, the court must then determine whether the asserted governmental interest is substantial.

- If both the first and second questions are answered affirmatively, the court assesses whether the regulation directly and materially advances the governmental interest asserted.

- Finally, the court evaluates whether the regulation is more extensive than necessary to serve that interest, i.e., if it is narrowly tailored to secure the governmental interest.

The Central Hudson test has been applied in numerous cases, such as Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), where it was ruled that individuals had the right to advertise abortion services in Virginia even though the procedure was illegal in that state. In another case, Edenfield v. Fane (1993), the Supreme Court upheld the right of certified public accountants to directly solicit clients under the First Amendment.

While the Central Hudson test is the dominant test in commercial speech jurisprudence, it has faced criticism from some justices. For example, Justice Clarence Thomas called for its abandonment in 44 Liquormart v. Rhode Island (1996), arguing that it asks courts to weigh incompatible values and apply contradictory premises.

Prohibition: A Constitutional Amendment?

You may want to see also

Commercial speech is entitled to less protection if it is false or misleading

Commercial speech, which includes all forms of marketing such as advertising, labelling, and price information, is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment. However, it is entitled to less protection than non-commercial speech, such as political speech. This is because commercial speech is viewed as more objective and, therefore, its truth content can be more easily determined.

The Central Hudson test, established in 1980, is a mid-level or intermediate scrutiny test used by courts to determine how far the regulation of commercial speech can go before it violates the First Amendment. The test applies to commercial speech that is truthful and legal. Under this test, courts first determine whether the expression is protected by the First Amendment, meaning that it must relate to a lawful activity and not be false, deceptive, or misleading. If the court determines that the commercial speech is false or misleading, the government can freely regulate it without First Amendment constraints.

If the expression is found to be protected, the court must then ask whether the government has asserted a substantial interest in restricting the commercial speech. If the answer is yes, the court must then determine whether the regulation directly advances the governmental interest asserted and whether the restriction is more extensive than necessary to serve that interest.

For example, in 1996, the Supreme Court used a four-pronged test to consider the government's interest in limiting price information in alcohol advertisements and ultimately struck down the law, ruling that it violated the First Amendment. In another case, the Supreme Court upheld a ban on broadcast lottery ads, applying the Central Hudson principles and finding that the government's interest in restricting commercial speech was legitimate.

Amending the Constitution: Adapting to a Changing World

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Commercial speech includes all forms of marketing, such as advertising, labelling, and price information.

Commercial speech is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment, but it does not receive as much free speech protection as non-commercial speech, such as political speech.

The Central Hudson test is a mid-level test developed by the Court to determine protection for commercial speech. Under this test, courts first determine whether the expression is protected by the First Amendment, and if so, whether the government has a substantial interest in restricting the speech, whether the regulation directly advances this interest, and whether the restriction is more extensive than necessary.

Some examples include Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), which established that commercial advertising should receive First Amendment protection, and 44 Liquormart v. Rhode Island (1996), which advanced First Amendment protections for commercial speech by striking down a state law banning the advertising of alcohol prices.

Yes, commercial speech can be compelled by the government as long as it includes "purely factual and uncontroversial information" that is reasonably related to the government's interest and helps to prevent consumer confusion or deception.

![First Amendment Rights: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81VXEV7XgxL._AC_UY218_.jpg)