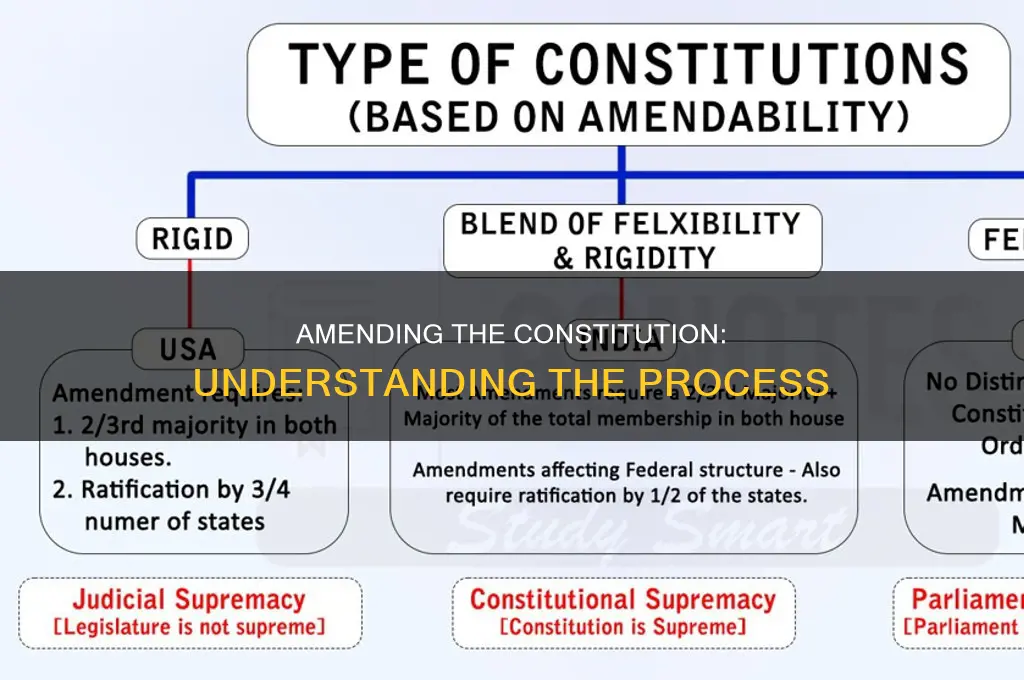

Article V of the United States Constitution outlines the procedure for amending the Constitution. It establishes two methods for proposing amendments: the first requires a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate, while the second involves a convention for proposing amendments called by Congress at the request of two-thirds of state legislatures. Amendments become operative once ratified by three-quarters of state legislatures or conventions. This article also specifies that the President has no constitutional role in the amendment process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Article of the Constitution that discusses the amendment process | Article V |

| Authority to amend the Constitution | The Congress, whenever two-thirds of both Houses deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments |

| Alternative Authority to amend the Constitution | On the application of the legislatures of two-thirds of the several states, a convention for proposing Amendments shall be called |

| Ratification | Ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three-fourths thereof |

| Requirements for Ratification | No requirement for presidential approval before it goes out to the states |

| Role of the President | The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process |

| Role of the Archivist | The Archivist of the United States is responsible for administering the ratification process and officially notifying the states |

| Number of Amendments Proposed by Congress | Congress has proposed 33 amendments, of which 27 have been ratified by the states |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The role of Congress

Article V of the United States Constitution outlines the process by which the Constitution may be amended, and it grants Congress a significant role in this process. Congress has used Article V's procedures to propose amendments to the Constitution.

Congress has two methods for proposing amendments. The first method, which has been used for all 33 amendments submitted to the states for ratification, requires a two-thirds vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This method involves Congress directly proposing amendments, which become valid once ratified by three-fourths of state legislatures or conventions. The second method, which has never been used, is for Congress to call a convention for proposing amendments at the request of two-thirds of state legislatures.

Congress plays a crucial role in initiating the amendment process by proposing amendments through these two methods. However, it is important to note that Congress does not have the final say in the ratification of amendments. While Congress can choose whether ratification will occur through state legislatures or state conventions, it is the states that ultimately decide whether to ratify or reject a proposed amendment. Each state's vote carries equal weight, and there is no requirement for presidential approval.

Once an amendment is ratified by three-fourths of the states, it becomes an operative part of the Constitution without requiring any further action from Congress. The Archivist of the United States is responsible for administering the ratification process and notifying the states of proposed amendments. While Congress may adopt a resolution declaring the process successfully completed, such actions are constitutionally unnecessary.

In summary, Congress plays a central role in proposing amendments to the Constitution and setting the ratification process in motion. However, the ultimate decision-making power lies with the states, and the ratification process is finalised without requiring further involvement from Congress.

Progressive Reform: Constitutional Amendment Impact

You may want to see also

Ratification by states

The authority to amend the Constitution of the United States is derived from Article V of the Constitution. After an amendment is proposed by Congress, the Archivist of the United States, who is at the helm of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), is tasked with overseeing the ratification process as per 1 U.S.C. 106b. Notably, neither Article V of the Constitution nor 1 U.S.C. 106b outline the ratification process in detail. Instead, the Archivist and the Director of the Federal Register follow the procedures and customs previously established by the Secretary of State and the Administrator of General Services.

Once an amendment is proposed by Congress, the original document is sent directly to NARA's Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication. The OFR then compiles an information package for the states, which includes "red-line" copies of the joint resolution, copies of the joint resolution in slip law format, and the statutory procedure for ratification under 1 U.S.C. 106b. The Archivist then sends a letter of notification to each state governor, along with the informational material prepared by the OFR.

For an amendment to become part of the Constitution, it must be ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures (38 out of 50 states). Alternatively, as determined by Congress, ratification can occur through conventions in three-fourths of the states, although this method has only been used once in American history, during the 1933 ratification of the 21st Amendment. Once the OFR confirms receiving the required number of authenticated ratification documents, a formal proclamation is drafted for the Archivist to certify that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution.

The certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the nation that the amendment process is complete. In recent times, the signing of the certification has taken on a ceremonial aspect, with various dignitaries, including the President, witnessing the event. Despite the President's presence at the ceremony, it is important to note that they do not have a constitutional role in the amendment process.

Approval Needed for Constitutional Amendments

You may want to see also

The President's involvement

The US Constitution derives its authority to be amended from Article V. While the President of the United States has no formal constitutional role in the amendment process, they have played an informal and ministerial role in some instances.

The process of amending the Constitution begins with a proposal by Congress, which must be passed by a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This proposal is made in the form of a joint resolution, which does not require the signature or approval of the President. Instead, the original document is sent directly to the National Archives and Records Administration's (NARA) Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication. The OFR is responsible for administering the ratification process and follows established procedures and customs.

The President has, on occasion, signed joint resolutions related to amendments. For example, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, and President Jimmy Carter signed a resolution to extend the deadline for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. However, these signatures were not necessary for the proposal or ratification of the amendments. Additionally, the President may be involved in a ceremonial capacity during the signing of the certification of an amendment, as witnessed by Presidents Johnson, Nixon, and others.

While the President's involvement in the amendment process is not constitutionally mandated, their presence during ceremonial functions or their signature on non-binding resolutions can be seen as a symbolic gesture of support for the amendment process.

Amendments: The Constitution's Living Evolution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Archivist's role

The Archivist has delegated many of the ministerial duties associated with this function to the Director of the Federal Register. However, the Archivist plays a crucial role in certifying the validity of an amendment. Once the OFR verifies that it has received the required number of authenticated ratification documents, it drafts a formal proclamation for the Archivist to certify. This certification confirms that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution.

The Archivist's certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the nation that the amendment process is complete. This certification is a significant step in the amendment process, and in recent history, it has become a ceremonial function attended by dignitaries, including the President on some occasions.

It is important to note that the Archivist does not make any substantive determinations regarding the validity of state ratification actions. However, their certification of the facial legal sufficiency of ratification documents is final and conclusive. Overall, the Archivist's role in the amendment process is essential to ensuring the smooth and proper implementation of constitutional changes in the United States.

Amendments: Our Constitution's Living Legacy

You may want to see also

Article V's history

Article V of the US Constitution outlines the process for amending the document. It establishes two methods for proposing amendments: the first requires a two-thirds vote in both the House and Senate, while the second involves a convention for proposing amendments called by Congress at the request of two-thirds of state legislatures.

The history of the amendment process is a long and fascinating one. Since 1789, the first method for crafting and proposing amendments has been predominantly used, with 33 amendments submitted to the states for ratification originating in Congress. This method involves a joint resolution, which does not require presidential approval, being forwarded directly to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) for processing and publication. The NARA's Office of the Federal Register (OFR) then adds legislative history notes and publishes the resolution in slip law format, before sending an information package to the states for their consideration.

The second method, the convention option, has yet to be invoked. This method would allow state legislatures to have a greater say in the amendment process and act as a check on the national authority, as argued by Alexander Hamilton.

Once an amendment is proposed, it must be ratified to become part of the Constitution. Ratification can occur through the legislatures of three-quarters of the states or by ratifying conventions in three-quarters of the states, as determined by Congress. The OFR verifies the receipt of the required number of authenticated ratification documents and drafts a formal proclamation for the Archivist to certify that the amendment is valid. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the nation that the amendment process is complete.

In recent history, the signing of the certification has become a ceremonial function attended by dignitaries, including the President. The process outlined in Article V has been used to propose and ratify 27 amendments, with six additional amendments proposed by Congress but not ratified by the states.

Amendments: The Constitution's Formal Changes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Article V of the US Constitution outlines the procedure for altering the Constitution.

Amendments can be proposed by Congress with a two-thirds vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or by a convention called by Congress at the request of two-thirds of state legislatures. To become part of the Constitution, an amendment must be ratified by three-quarters of the state legislatures or by ratifying conventions in three-quarters of the states.

The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, and any proposed amendments do not require presidential approval.