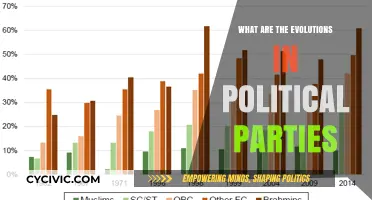

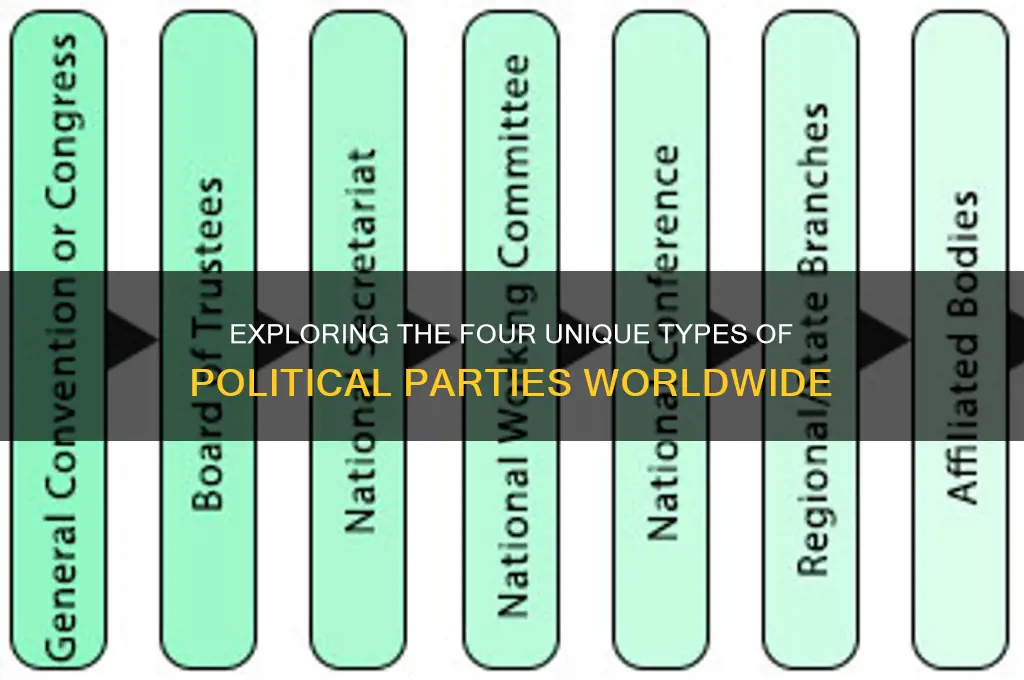

Political parties are essential components of democratic systems, serving as vehicles for organizing political interests, mobilizing voters, and shaping public policy. While the structures and ideologies of political parties vary widely across countries, they can generally be categorized into four distinct types: cadre parties, mass parties, catch-all parties, and cartel parties. Cadre parties are elite-driven organizations with a small, dedicated membership focused on influencing policy and governance. Mass parties, emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, aim to represent broad segments of society and rely on large memberships for support. Catch-all parties, prominent in the post-World War II era, seek to appeal to a wide range of voters by moderating their ideologies and prioritizing electability. Finally, cartel parties, a more recent phenomenon, are characterized by their reliance on state funding and a focus on maintaining power through cooperation with other parties, often at the expense of ideological purity. Understanding these types provides insight into how parties function, adapt, and compete in modern political landscapes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mass-Based Parties: Broad appeal, large membership, diverse ideologies, focus on public participation, and grassroots support

- Cadre Parties: Small, elite-driven, ideologically focused, limited membership, and professional leadership

- Elite Parties: Represent wealthy or powerful groups, exclusive, policy-oriented, and influence-driven

- Protest Parties: Single-issue focused, anti-establishment, temporary, and often populist in nature

- Charismatic Parties: Centered around a leader, personality-driven, emotional appeal, and less structured ideology

Mass-Based Parties: Broad appeal, large membership, diverse ideologies, focus on public participation, and grassroots support

Mass-based parties thrive on their ability to mobilize vast, diverse populations, often transcending narrow ideological boundaries to unite people under a common cause. Unlike cadre parties, which rely on a small, elite group of organizers, mass-based parties draw strength from their sheer numbers. Consider the Indian National Congress, which has historically appealed to a wide spectrum of voters across regions, religions, and socioeconomic classes. Its success lies in its ability to engage millions through grassroots campaigns, local chapters, and inclusive messaging that resonates with both urban professionals and rural farmers.

To build a mass-based party, focus on broadening your appeal rather than deepening ideological purity. Start by identifying shared concerns that cut across demographic lines, such as economic inequality, healthcare access, or environmental sustainability. For instance, the Labour Party in the UK has long championed policies like universal healthcare and workers’ rights, attracting members from trade unions, middle-class professionals, and marginalized communities alike. Practical tip: Use surveys, town hall meetings, and social media analytics to identify overlapping priorities among your target audience.

A critical aspect of mass-based parties is their emphasis on public participation. This isn’t just about voting—it’s about actively involving members in decision-making, policy formulation, and campaign activities. The African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, for example, maintains a robust network of local branches where members debate issues, elect leaders, and organize community initiatives. To replicate this, establish clear pathways for members to contribute, such as volunteer programs, policy committees, or digital platforms for feedback. Caution: Avoid tokenism; ensure participation translates into tangible influence over party direction.

Diverse ideologies within mass-based parties can be both a strength and a challenge. While they allow for a broader coalition, they also risk internal fragmentation. The Democratic Party in the U.S. exemplifies this dynamic, encompassing progressives, moderates, and conservatives. To manage ideological diversity, adopt a pragmatic approach: prioritize unifying goals over divisive issues, and use consensus-building mechanisms like caucuses or issue-based task forces. For instance, the Brazilian Workers’ Party (PT) has successfully balanced socialist and centrist factions by focusing on anti-poverty programs and social justice.

Finally, grassroots support is the lifeblood of mass-based parties. This means investing in local leaders, community outreach, and sustained engagement beyond election cycles. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey, for instance, built its dominance by addressing everyday concerns like infrastructure and education at the neighborhood level. Practical tip: Allocate at least 30% of your party’s budget to grassroots initiatives, such as training local organizers, funding community projects, or hosting regular door-to-door campaigns. Takeaway: Mass-based parties aren’t just about winning elections—they’re about building a movement that endures through active, inclusive, and localized participation.

Political Parties: Strengthening or Weakening American Democracy?

You may want to see also

Cadre Parties: Small, elite-driven, ideologically focused, limited membership, and professional leadership

Cadre parties, often operating in the shadows of larger political movements, are the specialized forces of the political world, akin to elite military units. These parties are characterized by their small size, exclusive membership, and unwavering ideological focus. Imagine a tightly knit group of political strategists and intellectuals, bound by a shared vision, who meticulously plan and execute their agenda with precision. This is the essence of a cadre party.

The Anatomy of a Cadre Party

At the core of these parties lies a dedicated leadership, often comprising seasoned politicians, academics, or activists. These individuals are the architects, shaping the party's ideology and strategy. Membership is highly selective, attracting only those who demonstrate a deep commitment to the party's principles. This exclusivity fosters a sense of unity and purpose, creating a powerful bond among members. For instance, the early stages of the Bolshevik Party in Russia exemplified this structure, with Vladimir Lenin and a small group of revolutionaries forming the core, driving the party's radical agenda.

Ideology as the North Star

Cadre parties are defined by their unwavering dedication to a specific ideology. Whether it's socialism, conservatism, or environmentalism, the ideology becomes the party's raison d'être. Every action, policy proposal, and campaign is a means to advance this ideological agenda. This focus allows cadre parties to develop a clear, consistent message, attracting like-minded individuals and creating a distinct political identity. Consider the Green Parties in various countries, which have consistently advocated for environmental sustainability, often with a small but dedicated membership driving their agenda.

Strategy and Influence

Despite their limited numbers, cadre parties can exert significant influence. They achieve this through strategic alliances, targeted campaigns, and intellectual contributions to political discourse. By positioning themselves as experts and thought leaders, they can shape public opinion and policy. For instance, a small cadre party focused on economic reform might publish research, host seminars, and engage with media to promote their ideas, gradually gaining traction and influencing mainstream political parties.

Challenges and Trade-offs

The very nature of cadre parties presents unique challenges. Their small size can limit resources and reach, making it difficult to compete with mass-membership parties. Additionally, the elite-driven structure may lead to internal power struggles and a disconnect from the broader electorate. Balancing ideological purity with practical politics is a constant tightrope walk. However, when successfully navigated, these parties can become powerful catalysts for change, offering a focused and passionate alternative to mainstream politics.

In the spectrum of political parties, cadre parties occupy a unique niche, demonstrating that size is not always indicative of impact. Their influence lies in their ability to harness the power of a dedicated few, driving political agendas with precision and ideological fervor.

Creating a New Political Party in the US: Possibilities and Challenges

You may want to see also

Elite Parties: Represent wealthy or powerful groups, exclusive, policy-oriented, and influence-driven

Elite parties, by definition, are the gatekeepers of power, representing the interests of the wealthy and influential. These parties are not for the masses; they are exclusive clubs where membership is often inherited or earned through significant financial or social capital. Think of them as the VIP lounges of the political arena, where the elite gather to shape policies that maintain their dominance. For instance, in many countries, conservative parties have historically been associated with the upper echelons of society, advocating for low taxes on high incomes and deregulation that benefits corporate giants.

To understand their modus operandi, consider the following steps: First, identify the core constituency—typically a small, affluent group with shared economic goals. Second, craft policies that protect and expand their wealth, such as tax cuts for the rich or subsidies for industries they control. Third, leverage their financial resources to influence elections, often through campaign donations or media control. This strategy ensures that the party remains a vehicle for the elite’s agenda, rather than a platform for broader societal change.

However, this exclusivity comes with risks. Elite parties often face criticism for being out of touch with the average citizen’s needs. For example, while they may successfully push for policies that boost corporate profits, they might neglect issues like healthcare access or education funding, which disproportionately affect lower-income groups. This disconnect can lead to public backlash, as seen in recent populist movements that challenge the dominance of traditional elite-driven parties.

A comparative analysis reveals that elite parties differ sharply from mass-based parties, which aim to mobilize large segments of the population. While mass-based parties focus on inclusivity and broad appeal, elite parties prioritize precision and control. For instance, the Republican Party in the United States often aligns with corporate interests, whereas the Democratic Party, though not immune to elite influence, tends to emphasize broader social welfare programs. This contrast highlights the unique role of elite parties in maintaining the status quo for their constituents.

In practical terms, if you’re analyzing an elite party’s impact, start by tracing its funding sources. Campaign finance records, corporate donations, and lobbying activities can reveal the extent of elite influence. Additionally, examine the party’s policy track record—do their legislative achievements disproportionately benefit the wealthy? Finally, assess their communication strategies. Elite parties often use sophisticated messaging to frame their policies as beneficial to society at large, even when the primary beneficiaries are a select few. By dissecting these elements, you can uncover the mechanisms through which elite parties wield power and shape political landscapes.

Did George Washington Spark the First Political Party?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $14.99

Protest Parties: Single-issue focused, anti-establishment, temporary, and often populist in nature

Protest parties emerge as a distinct phenomenon in the political landscape, characterized by their laser-like focus on a single issue, their vehement rejection of the established political order, and their often fleeting existence. These parties are not built to govern; they are vehicles for dissent, amplifying the voices of those who feel marginalized or ignored by mainstream politics. Consider the Five Star Movement in Italy, which began as a protest against corruption and the political elite, or UKIP in the UK, whose singular focus on Brexit reshaped British politics before its influence waned. These examples illustrate how protest parties can disrupt the status quo, even if their impact is temporary.

The populist nature of protest parties is both their strength and their Achilles' heel. By framing politics as a battle between "the people" and "the elite," they tap into widespread frustration and disillusionment. However, this populist rhetoric often oversimplifies complex issues, offering easy answers to difficult questions. For instance, Greece's Syriza rose to power on a wave of anti-austerity sentiment but struggled to deliver on its promises once in government. This highlights a critical tension: protest parties are effective at mobilizing anger but often lack the infrastructure or policy depth to sustain long-term influence.

To understand the lifecycle of a protest party, think of it as a three-stage process: mobilization, peak influence, and decline. In the first stage, the party harnesses public outrage over a specific issue, such as immigration, economic inequality, or environmental degradation. The second stage sees the party achieve electoral success, often at the expense of traditional parties. However, the third stage is almost inevitable—as the party either fails to deliver on its promises or shifts toward becoming a more conventional political force, it loses its core identity and support base. This pattern is evident in the trajectory of Germany's Pirate Party, which surged in popularity over internet freedom issues but quickly faded as its single-issue focus lost relevance.

For those considering supporting or forming a protest party, it’s essential to weigh the trade-offs. On one hand, these parties can force mainstream politicians to address neglected issues and inject urgency into public debates. On the other hand, their temporary nature and lack of comprehensive policy platforms can lead to frustration and disillusionment among supporters. Practical advice: if you’re drawn to a protest party, ask yourself whether its goals align with your broader values and whether it has a realistic plan beyond its core issue. Remember, protest parties are tools for change, not blueprints for governance.

In conclusion, protest parties serve as a barometer of public discontent, a mechanism for holding established powers accountable, and a reminder of the fluidity of political systems. While their impact is often short-lived, their ability to shake up the political landscape cannot be underestimated. Whether you view them as catalysts for progress or as fleeting expressions of frustration, their role in modern democracy is undeniable. The challenge lies in channeling their energy into meaningful, lasting change rather than letting it dissipate into the void of political history.

Understanding Weld Politics: Strategies, Influence, and Power Dynamics Explained

You may want to see also

Charismatic Parties: Centered around a leader, personality-driven, emotional appeal, and less structured ideology

Charismatic parties are political entities that thrive on the magnetism and appeal of a central leader, often overshadowing formal ideologies or organizational structures. These parties are defined by their reliance on the leader’s personality, their ability to evoke emotional responses from followers, and their tendency to prioritize loyalty to the leader over rigid policy frameworks. Unlike traditional parties with well-defined platforms, charismatic parties derive their strength from the leader’s vision, rhetoric, and ability to connect with the masses on a visceral level.

Consider the case of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. His leadership transformed the country’s political landscape by blending populist rhetoric with emotional appeals to the working class. Chávez’s charisma allowed him to dominate the political narrative, often overshadowing the specifics of his policies. His party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), became synonymous with his persona, and its success hinged on his ability to inspire loyalty and hope among followers. This example illustrates how charismatic parties can achieve significant political influence through the force of personality rather than detailed ideological blueprints.

However, the reliance on a single leader carries inherent risks. Charismatic parties often struggle to maintain cohesion and direction after the leader’s departure. Without a structured ideology or institutional framework, the party’s identity can crumble, leading to fragmentation or irrelevance. For instance, the Peronist movement in Argentina, centered around Juan Perón, faced repeated challenges in sustaining its influence beyond his leadership. This vulnerability underscores the double-edged nature of charisma-driven politics: while it can mobilize masses, it often lacks the resilience of ideologically grounded movements.

To build a charismatic party effectively, focus on three key strategies. First, cultivate a leader who embodies the aspirations and frustrations of the target audience. This requires a deep understanding of the demographic’s emotional and psychological needs. Second, leverage storytelling and symbolism to create a narrative that resonates with followers. Chávez’s use of Bolivarian imagery and anti-imperialist rhetoric is a prime example. Third, maintain flexibility in policy positions to adapt to shifting public sentiments, as rigid ideologies can alienate potential supporters.

In conclusion, charismatic parties offer a powerful but precarious model for political mobilization. Their strength lies in their ability to inspire and unite through personality and emotion, but their weakness stems from their dependence on a single figure and lack of structured ideology. For practitioners, the challenge is to harness the energy of charisma while building institutional mechanisms that ensure longevity. Done right, such parties can reshape political landscapes; done wrong, they risk becoming fleeting phenomena tied to the lifespan of their leader.

Is the Democratic Socialists of America a Political Party?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The four distinct types of political parties are cadre parties, mass parties, catch-all parties, and cartel parties, each defined by their organizational structure, membership base, and strategies.

A cadre party is a type of political party characterized by a small, elite group of leaders and activists who focus on policy development and governance, with limited mass membership involvement.

A mass party is distinguished by its large, ideologically driven membership base, strong grassroots organization, and focus on mobilizing supporters around a specific political agenda or ideology.

A catch-all party aims to appeal to a broad spectrum of voters by moderating its policies and emphasizing pragmatic solutions rather than rigid ideologies, often prioritizing electoral success over ideological purity.

A cartel party is a type of political party that relies heavily on state funding and professionalized structures, often prioritizing cooperation with other parties and institutional stability over direct engagement with the electorate.

![Earth Party! An Early Introduction to the Linnaean System of Classification of Living Things Unit Study [Student Book]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61jwqSZsUmL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Earth Party! An Early Introduction to the Linnaean System of Classification of Living Things Unit Study [Teacher's Book]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61PqBE09giL._AC_UL320_.jpg)