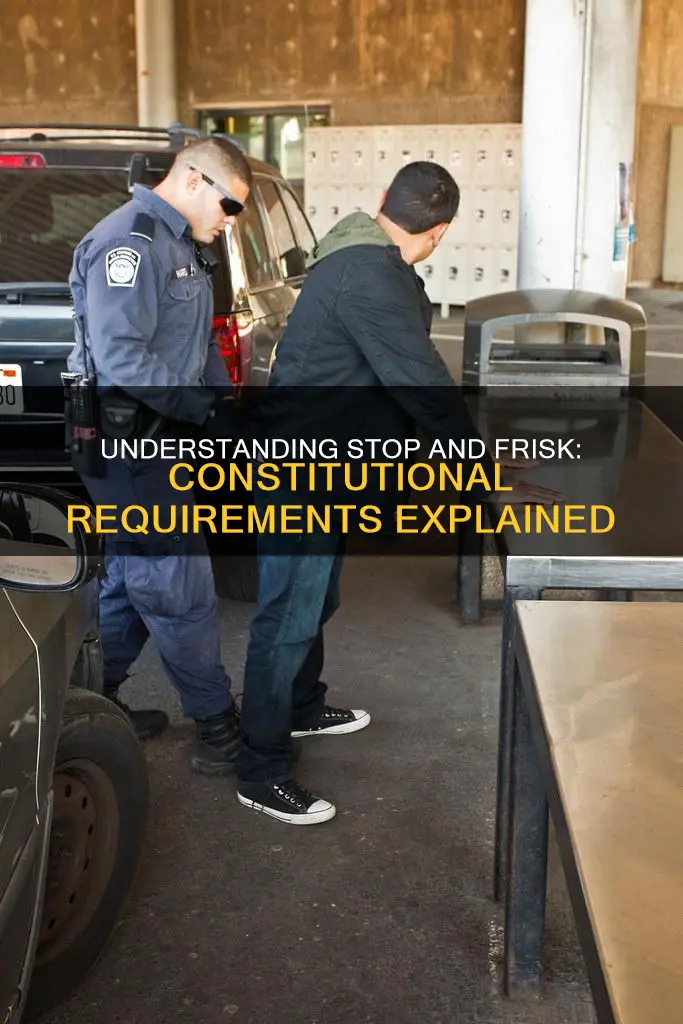

The constitutional requirements for stop and frisk searches in the United States are informed by the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Supreme Court has upheld the practice of stop and frisk, but it must be based on reasonable suspicion, good cause, and articulable suspicion. Officers are permitted to pat down the outer clothing of individuals they reasonably suspect may be armed and dangerous, but the search must be minimally invasive and cannot be a full-scale seizure. The scope of the search is limited to what is absolutely necessary, and officers must articulate their fear that the suspect is armed for the stop and frisk to be valid. The use of stop and frisk has been controversial, with critics arguing that it leads to racial profiling and discrimination. While a federal judge declared New York City's stop-and-frisk policy unconstitutional in 2013 due to statistical evidence of disproportionate targeting of people of color, the practice remains lawful and widely used.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reason for stop and frisk | Reasonable suspicion that a crime is about to take place |

| Reasonable suspicion that the suspect is armed and dangerous | |

| Officer safety is at risk | |

| Scope | Must be within reach |

| Must last only a short while | |

| Must be confined to discovering weapons | |

| Must be a pat down of the exterior clothing of the suspect | |

| Discrimination | Courts will scrutinize the officer's actions if discrimination is suspected |

| Cannot use race to judge whether a person appears suspicious or dangerous |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

'Reasonable suspicion' and 'probable cause'

The Fourth Amendment requires that police have a reasonable suspicion that a crime has been, is being, or is about to be committed by a suspect before stopping them. This is a flexible standard that falls somewhere between a whim and probable cause. Reasonable suspicion requires more than an unarticulated hunch or a bare, imaginary, or purely conjectural suspicion. It requires facts or circumstances that would lead a reasonable person to suspect that a crime was committed, is being committed, or will be committed imminently.

Reasonable suspicion permits some stops and questioning without probable cause to allow police to explore the basis for their suspicions. However, extensive intrusions on individual privacy, such as transportation to a police station for interrogation and fingerprinting, are not allowed without probable cause.

In the context of stop and frisk, the Supreme Court in Terry v. Ohio held that an officer may conduct a pat-down of a suspect's outer clothing if they have a reasonable suspicion that the suspect is armed and dangerous. The purpose of the pat-down is to ensure officer safety or the safety of others. The Court emphasized that the stop must be brief and within the officer's reach, and the officer must articulate their fear that the suspect is armed.

The presence of reasonable suspicion is determined by the totality of the circumstances, and officers must be able to articulate specific facts that led to their suspicion. For example, in Arizona v. Johnson, the Supreme Court held that during a traffic stop, officers need not have a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity to frisk passengers but must have a reason to believe they are armed and dangerous.

While reasonable suspicion is a lower standard than probable cause, it is still subject to constitutional boundaries and local police guidelines. Courts will carefully scrutinize an officer's actions if discrimination is suspected, and statistical evidence has been used to challenge stop-and-frisk policies as unconstitutional.

The Constitution: American Indians' Plight

You may want to see also

Discrimination and racial profiling

The constitutional requirements for stop and frisk searches are based on the 1968 Supreme Court case, Terry v. Ohio. The Court ruled that law enforcement officers could stop and pat down a suspect if they had a ""reasonable suspicion" that the person may be armed and dangerous. The Court defined "reasonable suspicion" as a belief that "a reasonably prudent officer is warranted in the circumstances of a given case." This means that the officer must have a justifiable reason to suspect that a person is carrying a weapon and poses a threat to themselves or others. The Court also set scope limitations, stating that the search must be brief, within reach, and limited to a pat-down of the suspect's exterior clothing.

However, the stop and frisk policy has been criticised for its disproportionate impact on people of colour, particularly Black people, and its role in racial profiling. In New York City, for example, data revealed that Black and Latino people comprised more than 80% of those searched, and Blacks were five times more likely to be searched than whites. Similar patterns have been observed in Detroit, where the policy has been accused of expanding police powers, targeting minority citizens, and leading to widespread racial profiling. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other groups have argued that the police use race as a factor in determining suspicion or danger, which violates the Constitution.

The debate surrounding stop and frisk centres on addressing racial disparities and preventing law enforcement from engaging in racial profiling. While civil rights activists have challenged these practices, stop and frisk remains lawful and prevalent in the United States. The Supreme Court's interpretation of "reasonable suspicion" grants officers significant discretion in conducting stops, which has contributed to concerns about the potential for abuse and the targeting of specific racial groups.

To address these concerns, some cities have implemented measures to limit the abuse of stop and frisk. For instance, New York City announced plans to reform its stop-and-frisk policy to prevent discriminatory Terry stops. Additionally, the release of data by police departments enables organisations like the NYCLU to advocate for change and ensure that police practices are fair and free from racial bias.

Dragon's Constitution: A Powerful D&D 5e Advantage

You may want to see also

Officer safety

The Fourth Amendment requires that before stopping a suspect, the police must have a reasonable suspicion that a crime has been, is being, or is about to be committed by that person. If the police have a reasonable belief that the suspect is armed and dangerous, they may frisk them, or perform a quick pat-down of their outer clothing. This is also called a Terry Stop, derived from the Supreme Court case, Terry v. Ohio, where the Court ruled that officers have the right to stop and frisk a suspect if they have reasonable suspicion that the person may be armed. The basis for this decision was officer safety.

In the case of Terry v. Ohio, the Court held that a stop-and-frisk must comply with the Fourth Amendment, meaning that the stop-and-frisk cannot be unreasonable. The Court defined a reasonable stop-and-frisk as one "in which a reasonably prudent officer is warranted in the circumstances of a given case in believing that his safety or that of others is endangered, he may make a reasonable search for weapons of the person believed by him to be armed and dangerous."

In another case, Sivron v. New York, the Court ruled that police officers must articulate their fear that the suspect is armed for the stop and frisk to be valid. The Court also set scope limitations for the stop-and-frisk, stating that it cannot be a full-scale seizure of a person, it must be within reach, and it must last only a short while. Police officers can frisk a suspect only for what is absolutely necessary, such as looking for a weapon, and the search must be limited to a pat down of the exterior clothing of the suspect.

Officers must remain within constitutional boundaries and comply with local police guidelines. In cases where the court suspects discrimination, the judge will carefully scrutinize the officer's actions. While stop-and-frisk remains lawful and widely used throughout the United States, there is an ongoing debate about how to prevent law enforcement from engaging in racial profiling when deciding whom to stop and frisk.

The Police and the Constitution: Upholding the Law?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$30.15 $34.99

Scope limitations

- Reasonable Suspicion: A stop and frisk search must be based on reasonable suspicion that the person may be armed and dangerous. This suspicion must be supported by specific and articulable facts that would lead a neutral magistrate to conclude that an investigative stop and frisk was warranted. The standard of "reasonable suspicion" is lower than that of "probable cause," giving officers greater discretion in authorizing searches.

- Officer Safety: The primary objective of a stop and frisk search is to ensure the safety of the officer or others who may be endangered by an armed individual. The search must be limited to what is necessary to achieve this objective.

- Limited Scope of Search: The search must be confined to an intrusion reasonably designed to discover weapons. Officers are allowed to pat down the exterior clothing of the suspect to check for weapons but cannot conduct a full-scale seizure or an extensive search.

- Time Limitations: A stop and frisk search cannot be prolonged beyond the time reasonably required to address the initial reason for the stop. The Supreme Court has held that a police stop exceeding this time violates the Constitution's protection against unreasonable seizures.

- Discrimination and Racial Profiling: Courts have scrutinized stop and frisk practices to ensure they are not discriminatory or based on racial profiling. In 2013, a federal judge declared New York City's stop-and-frisk policy unconstitutional due to statistical evidence suggesting officers disproportionately targeted people of color. While this decision was blocked by an appeals court, it highlights the scope limitation regarding discrimination.

- Warrant Requirements: While the Supreme Court has ruled that a stop and frisk does not require a warrant, it must still comply with the Fourth Amendment's prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures. The absence of a warrant does not give officers unlimited authority to conduct stop and frisk searches.

These scope limitations aim to balance the need for officer safety and investigative effectiveness with the constitutional rights of individuals to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Who Confirms Presidential Cabinet Appointments?

You may want to see also

Search and seizure

The Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures. This includes stop and frisk searches, which are considered seizures and searches under the Fourth Amendment. While the US Supreme Court has upheld the practice of stop and frisk, there are constitutional boundaries that must be followed.

For a stop and frisk to be constitutional, it must be based on reasonable suspicion, good cause, and articulable suspicion. In Terry v. Ohio, the Court ruled that officers have the right to stop and pat down a suspect if they have a reasonable suspicion that the person may be armed and dangerous, thus endangering the safety of the officer or others. The Court also set scope limitations, stating that a stop and frisk cannot be a full-scale seizure, must be within reach, and must last only a short time. Police officers can only frisk a suspect for what is absolutely necessary, such as looking for a weapon, and the search must be limited to a pat down of the exterior clothing.

The standard for warrantless arrests and searches has been a topic of debate, with some arguing that ""probable cause"" should be the long-endorsed standard, while others contend that ""reasonable suspicion"" is sufficient. In the case of Terry v. Ohio, the Court ruled that ""reasonable suspicion"" was enough to justify a stop and frisk, as requiring ""probable cause"" would give judges greater discretion in authorizing searches. However, it's important to note that the Court also stated that a stop and frisk cannot be prolonged beyond the time needed to address the reason for the stop, and the scope of the frisk should be limited to ensuring officer safety.

The constitutionality of stop and frisk searches has been challenged on the grounds of racial profiling and discrimination. Civil rights groups, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), have argued that police use race as a factor in determining whether a person appears suspicious or dangerous. In 2013, a federal judge declared New York City's stop-and-frisk policy unconstitutional due to statistical evidence suggesting officers disproportionately targeted people of color. While this decision was blocked by a federal court of appeals, it sparked a debate about discriminatory practices in policing.

To ensure constitutional compliance, officers must follow local police guidelines and remain within the boundaries set by the Fourth Amendment. Courts will carefully scrutinize an officer's actions if discrimination is suspected. Additionally, individuals who believe they have been illegally stopped and frisked can seek legal counsel to protect their Fourth Amendment rights.

Immigrant Voting Rights: What Does the Constitution Say?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A stop and frisk search occurs when a police officer stops an individual for questioning and conducts a pat-down of their outer clothing to check for weapons.

The Fourth Amendment protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures. A stop and frisk search must be based on reasonable suspicion, good cause, and articulable suspicion. The officer must have reason to believe the individual is armed or involved in a crime.

The scope of a stop and frisk search is limited. It cannot be a full-scale seizure, must be brief, and must only involve a pat-down of the exterior clothing to search for weapons. Officers must also comply with local police guidelines.

If you believe your Fourth Amendment rights were violated, you should consult an experienced attorney who can review the specifics of your case and determine if your rights were infringed upon.