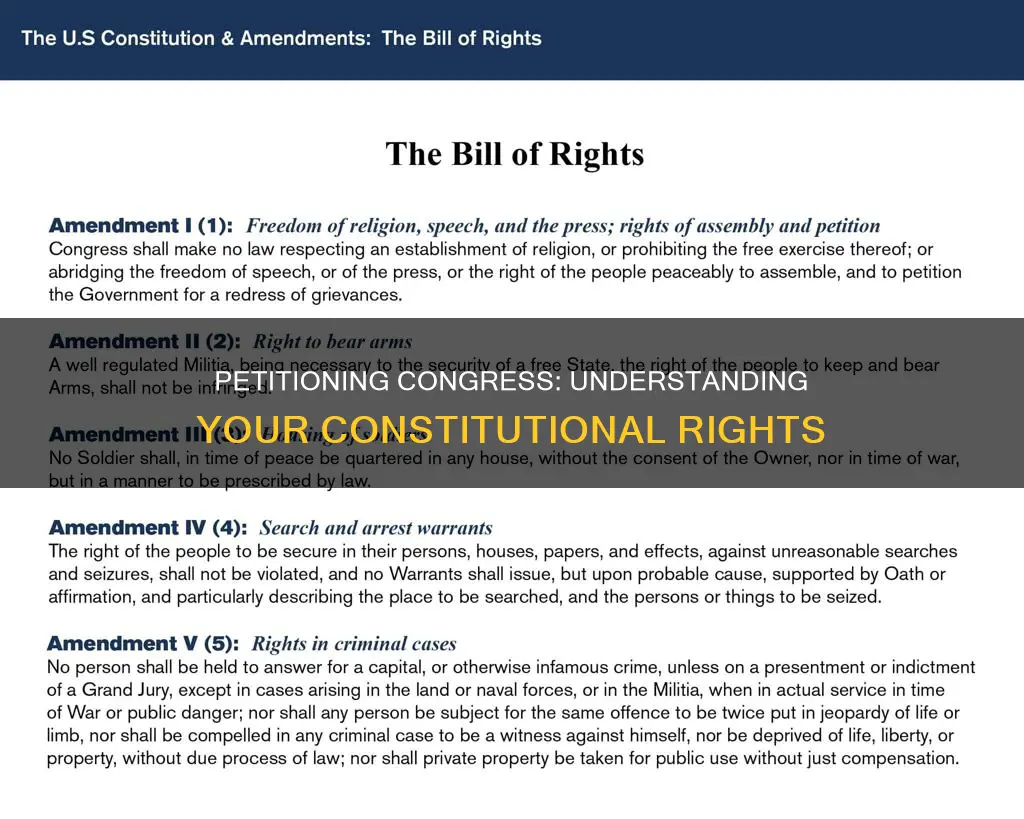

The right to petition is a fundamental aspect of democracy, enabling citizens to engage with the legislative process and hold their representatives accountable. This right is deeply rooted in the history of the United States, with its origins traced back to the Magna Carta in 1215. The First Amendment of the United States Constitution explicitly guarantees the right to petition, stating that Congress shall make no law abridging the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the Government for a redress of grievances. This constitutional provision has been interpreted as prohibiting government interference with petitioning activities, ensuring that citizens can freely express their concerns and seek redress from their government. While the right to petition has expanded over time, it remains an underutilized tool for many Americans, with challenges arising from legislative immunity and a reduced scope of petitioning access.

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The right to petition is protected by the First Amendment

The right to petition is a fundamental aspect of democracy, and it is protected by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The First Amendment states that "Congress shall make no law [...] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." This provision ensures that individuals have the right to assemble and petition their government without interference or restriction.

The right to petition has a long history, dating back to pre-Magna Carta England, when individuals petitioned the king for redress of grievances. It was first formally recognized in the Magna Carta of 1215 and later included in the English Bill of Rights of 1689. The right was then brought to the American colonies, where it was explicitly included in colonial charters and implicitly affirmed through widespread petitioning. The Founding Fathers considered the right to petition so important that they included it in the First Amendment, part of the Bill of Rights ratified in 1791.

Over time, the right to petition has evolved and expanded. It is no longer limited to demands for "a redress of grievances" but now includes demands for the government to act in the interest and prosperity of the petitioners and to address politically contentious matters. The Supreme Court has also played a role in shaping the right to petition, with cases like Smith v. Arkansas State Highway Employees clarifying that the right does not require government policymakers to listen or respond to petitions.

Despite being protected by the First Amendment, the right to petition Congress has been described as inconvenient and neglected in modern times. The scope of petitioning has been reduced, and there are barriers to accessing members of Congress. However, technology may provide a solution to these challenges, making it easier for citizens to organize grassroots campaigns and advocate for their rights.

In conclusion, the right to petition is a fundamental aspect of democracy, protected by the First Amendment. It has a long history and has evolved to encompass a broader range of demands. While it faces challenges in terms of accessibility and enforcement, it remains an important tool for citizens to engage with their government and advocate for change.

The Preamble: Constitution's Mission Statement

You may want to see also

The right to petition predates the US Constitution

The historical basis for the right to petition can also be traced to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The Declaration cited King George's failure to address the grievances listed in colonial petitions, such as the Olive Branch Petition of 1775, as a justification for declaring independence. This demonstrated the importance of the right to petition and the need for a government that responded to the people's concerns.

The US Constitution, in the First Amendment, specifically prohibits Congress from abridging "the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances". This right to petition has been interpreted as a fundamental aspect of democratic life, allowing citizens to engage with their government and seek action on politically contentious matters.

While the right to petition has been expanded and interpreted in various ways over time, it remains a crucial component of the US constitutional framework, protecting the rights of citizens to make their voices heard and hold their government accountable. The Supreme Court has acknowledged the significance of this right, even if it is often overlooked in favour of other more famous freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment.

The Constitution's Impact on Citizen Voting

You may want to see also

The right to petition is a cognate right

The right to petition is a fundamental freedom in the United States, as outlined in the First Amendment to the US Constitution. This right prohibits Congress from infringing on "the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the Government for a redress of grievances". The right to petition has evolved since the Constitution was written, and now includes demands for the government to act in the interest of petitioners and address their views on contentious political matters.

The historical basis of the right to petition can be traced back to the Magna Carta in 1215, which implicitly affirmed the right through its acceptance by the monarchy. The right was further developed in English statutory law in 1340, which required that a Commission be provided at every Parliament to "hear by petition delivered to them, the Complaints of all those that will complain them of such Delays or Grievances done to them".

The first significant exercise of the right to petition in the US was in the advocacy for the end of slavery. Over a thousand petitions on the topic, signed by around 130,000 citizens, were sent to Congress. Initially, the House of Representatives and the Senate adopted gag rules to indefinitely table anti-slavery petitions and prohibit their discussion. However, in 1844, these rules were repealed as being contrary to the Constitutional right to petition.

The right to petition is often considered a cognate right, related to the rights of free speech and a free press. Cognates, in the context of language, refer to words that sound similar, share the same meaning, and have a common linguistic ancestor. The right to peaceable assembly and the right to petition are often considered cognate rights, with the right to assemble being subordinate to the right to petition. This interpretation has evolved, and the rights are now often viewed as components of a single right, with the right to assemble protecting the interest in holding meetings for peaceable political action.

The Constitution: Conservative, Liberal, or Radical?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$42.55 $55.99

$12.95

The right to petition has been limited by the Supreme Court

The right to petition is a fundamental aspect of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which ensures that individuals can request the government for a redress of grievances without fear of retaliation. This right has been interpreted and limited by the Supreme Court in several ways.

Firstly, the Supreme Court has largely interpreted the Petition Clause as coextensive with the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. This interpretation suggests that the right to petition is subordinate to free speech and has been rendered obsolete by an expanding Free Speech Clause. However, in its 2010 decision in Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri, the Court acknowledged that there may be differences between the two clauses, recognising the Petition Clause as protecting the right of individuals to appeal to courts and other government forums for legal dispute resolution.

Secondly, the Supreme Court has placed limitations on the manner in which petitioning can occur. For example, in Brown v. Gilnes (1980), the Court held that base commanders could prevent military personnel from sending petitions to Congress, demonstrating less tolerance towards petitioning on military issues. The Court has also ruled on restrictions related to assemblies and protests, such as banning permit laws that give excessive discretion to local authorities while allowing for discretionary regulation by the police to maintain order and protect the rights of non-participants.

Thirdly, the Supreme Court has addressed the right to petition in the context of civil litigation and lobbying. It has been argued that lobbying, or persuading public officials, is a form of petitioning. However, the Court has rejected the notion that the government is required to listen to or respond to members of the public on public issues, differentiating between the rights to speak and petition.

Finally, the Supreme Court has considered the right to petition in relation to government employees. In Pickering v. Board of Education, the Court balanced the employee's right to free speech against the government's interest in efficient public services, setting a precedent for restricting employee grievances to administrative processes.

While the Supreme Court has placed some limitations on the right to petition, it has also played a role in reinforcing this right throughout history, protecting activities such as peaceful protests and union picketing.

Can Americans Own Tanks? The Constitution Explained

You may want to see also

The right to petition has been expanded by the Supreme Court

The right to petition has a long history in the United States, dating back to the Magna Carta in 1215. This right is enshrined in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits Congress from abridging "the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the Government for a redress of grievances". Despite its importance, the right to petition is often overlooked or taken for granted.

Over time, the Supreme Court has played a significant role in expanding and interpreting the right to petition. While the right initially referred specifically to petitioning the federal legislature, courts, and executive branches, the Supreme Court has broadened its scope through the incorporation doctrine, which now includes all state and federal courts, legislatures, and executive branches.

In interpreting the Petition Clause, the Supreme Court has often treated it as coextensive with the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. However, in the 2010 case of Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri, the Court acknowledged that there may be differences between the two clauses, recognising that the Petition Clause protects the right of individuals to appeal to courts and other government forums for the resolution of legal disputes.

The Supreme Court has also expanded the right to petition beyond written arguments to include other forms of democratic collective action, such as peaceful demonstrations and picketing. Notably, in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), the Court held that orderly union picketing was a protected form of assembly and petition, deeming the state law restricting it unconstitutional. Similarly, in Edwards v. South Carolina (1963), the Court upheld the right to petition by overturning the convictions of 180 African American students who had marched peacefully to protest racial discrimination.

In addition, the Supreme Court has clarified that the right to petition extends to all departments of the government, including administrative agencies and courts. This expansion ensures that citizens or groups can approach these entities with their concerns and demands.

While the Supreme Court has broadened the right to petition in significant ways, it has also placed some limitations. For example, in McDonald v. Smith (1985), the Court held that speech within a petition is subject to the same standards for defamation and libel as speech outside of it. Furthermore, the Court has ruled that the right to petition does not require government policymakers to listen to or respond to communications from the public.

Freshwater Sources: Where Is Earth's Water?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The right to petition is the right to assemble and petition the government for a redress of grievances. This right is derived from the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits Congress from abridging the freedom of speech and the right to peaceably assemble.

The right to petition can be traced back to English common law and pre-dates the Magna Carta, which was signed in 1215. The right was further formalised in the English Bill of Rights of 1689. American colonists brought this right to the colonies, and it was later included in the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the US Constitution in 1791.

The right to petition has been interpreted by the courts as a cognate right, promoting democracy and free speech. The Supreme Court has also acknowledged that there may be differences between the Petition Clause and the Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

Petitioning Congress is considered an inconvenient and neglected right, with the scope of petitioning having been greatly reduced. Public opinion polls indicate that the perceived indifference of lawmakers to public interests is making Congress increasingly unpopular.

![The Struggle in Congress over Abolition Petitions / by Clarence Edwin Carter 1906 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)