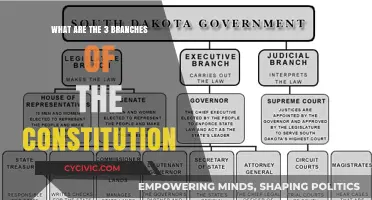

The US Constitution created a federalist system with powers divided between the national government and the states. The Enumerated Powers, listed in Article I, Section 8, outline 18 powers granted to Congress. These include the power to regulate immigration and naturalization, coin money, establish post offices, and grant patents and copyrights. The powers of Congress also include the ability to tax, declare war, and raise and regulate military forces. The interpretation of these powers has been controversial, with strict constructionists arguing for a limited interpretation, while loose constructionists believe it is up to Congress to determine the means necessary to execute its powers.

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The power to tax

The interpretation of the extent of Congress's power to tax has been a source of continued dispute. The disagreement centres around the General Welfare Clause and whether it grants an independent spending power or restricts the taxing power. James Madison, in Federalist 41, argued for a narrow interpretation, suggesting that spending must be connected to other enumerated powers. On the other hand, the broader view, supported by Justice Story and upheld in United States v. Butler, asserts that the General Welfare Clause gives Congress an independent power to tax and spend for matters affecting national welfare.

Texas Constitution of 1836: Religious Freedom Impact

You may want to see also

Regulation of commerce

The US Constitution created a federalist system with powers divided between the national government and the states. The powers of Congress are enumerated, meaning it can only exercise the powers granted to it by the Constitution.

Article I, Section 8 of the US Constitution outlines the powers of Congress, including the power to "regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes". This is often referred to as the Commerce Clause.

The Commerce Clause gives Congress broad power to regulate interstate commerce and restrict states from impairing interstate commerce. This power has been interpreted to include the regulation of things that "affect" interstate commerce." As a result, Congress has been able to regulate a wide range of activities and products, such as gambling and sawn-off shotguns, by taxing them.

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has been a subject of debate and controversy. Some argue that "commerce" refers simply to trade or exchange, while others claim that it describes a broader social intercourse between citizens of different states.

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in interpreting the Commerce Clause. Early Supreme Court cases primarily viewed the clause as limiting state power rather than as a source of federal power. However, in the 1937 case of NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp, the Court began to recognize broader grounds for using the Commerce Clause to regulate state activity. The Court held that any activity with a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce could be regulated under the clause.

In the 1995 case of United States v. Lopez, the Supreme Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad legislative mandate under the Commerce Clause by returning to a more conservative interpretation. In this case, the defendant argued that the federal government did not have the authority to regulate firearms in local schools. The Court agreed, holding that Congress only has the power to regulate the channels of commerce, the instrumentalities of commerce, and actions that substantially affect interstate commerce.

Appointment Letters: Employment Relationship Status?

You may want to see also

Declaration of war

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to declare war. This is known as the Declare War Clause, and it is one of the eighteen enumerated powers listed in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution.

The Declare War Clause gives Congress the exclusive power to formally and informally declare war. Formally declaring war involves issuing an official declaration of war, which announces a new hostile relationship. However, modern hostilities rarely begin with such a statement. For example, the Vietnam War was an "undeclared war" as no official statement was issued. Informal declarations of war can include authorizations for the use of military force, such as when Congress authorized the use of force to protect US interests and allies in Southeast Asia, leading to the Vietnam War.

The interpretation of the Declare War Clause has been a subject of debate. While it is generally accepted that the clause limits the President's power to initiate the use of military force, there is disagreement on the extent of this limitation. Some argue that the President has the authority to use defensive force in response to attacks, while others contend that the President's power may extend further, including the ability to respond with offensive force.

The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause, further complicates the understanding of war powers. This clause allows Congress to make laws necessary and proper for executing its enumerated powers, granting it significant leeway in interpretation. Strict constructionists argue that Congress should only make laws if not doing so would cripple its ability to apply its enumerated powers, while loose constructionists believe Congress has more flexibility in determining what is "necessary and proper". This clause has been used to justify the United States' inherent war powers, which derive from its role as a sovereign country.

Chronic Pain: Disability Rights Under the ADA

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Raising and supporting an army

The US Constitution enumerates 18 powers, most of which are listed in Article I, Section 8. One of these powers is the ability to "raise and support Armies". This power is a check on the President's commander-in-chief powers, as it gives Congress the authority to fund and regulate military forces.

The ability to raise and support an army is derived from the English King's historical power to initiate wars, raise armies, and maintain them. The Framers of the Constitution were aware that these powers had often been used to the detriment of English liberties and well-being. As such, they vested these powers in Congress, where they would be subject to greater scrutiny and debate.

Congress's power to raise and support armies includes the ability to classify and conscript manpower for military service. This power has been upheld by the Supreme Court, which has noted Congress's "broad constitutional power" in this area. However, there has been some opposition to conscription, with some arguing that it imposes involuntary servitude in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Congress also has the power to declare war and make rules concerning captures on land and water. This power acts as a check on the President's ability to conduct military operations once a war has begun. By controlling funding for military operations, Congress ensures that the will of the governed plays a role in any war effort.

To ensure that Congress's power to raise and support armies is not abused, the Constitution includes a limitation that "no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years". This limitation addresses the fear of standing armies and ensures that funding for the military is regularly reviewed and approved.

James Madison: Constitution's Father, Why?

You may want to see also

Congress's power over intellectual property

The US Constitution created a federalist system with powers divided between the national government and the states. Congress can exercise only the powers granted to it by the Constitution, most of which are listed in Article I, Section 8. One of these powers is the power to grant copyrights and patents to promote science and the arts. This power is referred to as Congress's power over intellectual property.

The IP Clause, also known as the Intellectual Property Clause, Copyright and Patent Clause, Exclusive Rights Clause, and Progress Clause, empowers Congress to grant authors and inventors exclusive rights to their writings and discoveries for a limited time. This clause provides the foundation for the federal copyright and patent systems.

A copyright gives authors (or their assignees) the exclusive right to reproduce, adapt, display, and/or perform an original work of authorship for a specified time period. This includes literary, musical, artistic, photographic, and audiovisual works. Similarly, a patent gives inventors (or their assignees) the exclusive right to make, use, sell, or import an invention that is new, non-obvious, and useful for a specified time period.

The Framers included the IP Clause in the Constitution to facilitate a uniform, national law governing patents and copyrights. In their view, the states could not effectively protect copyrights or patents separately. Under the Articles of Confederation, creators had to obtain copyrights and patents in multiple states under different standards, a difficult and expensive process that undermined the purpose and effectiveness of the legal regime.

While the IP Clause grants Congress the power to regulate intellectual property, it does not encompass all legal areas that may be considered intellectual property, such as trademarks and trade secrets.

Understanding the Constitution: A Guide to Reading and Reviewing

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US Constitution grants Congress 18 enumerated powers, mostly in Article I, Section 8. These include the power to regulate immigration and naturalization, coin money and regulate the currency, establish post offices, and grant patents and copyrights to promote science and the arts.

The US government has used its enumerated powers in various ways. For instance, Congress can set a national minimum drinking age by making it a condition of the grant of highway funds to states. They can also regulate almost anything by leveraging their power to regulate interstate commerce.

The US Constitution divides power between the national government and the states, creating a federalist system with limited or "enumerated" powers. The Tenth Amendment states that powers not delegated to the US government by the Constitution are reserved for the states or the people.

There are two primary schools of thought on interpreting the US government's enumerated powers: strict constructionism and loose constructionism. Strict constructionists interpret the Necessary and Proper Clause to mean that Congress may make laws only if not doing so would cripple its ability to apply an enumerated power. Loose constructionists, including Justice Marshall, believe it is up to Congress to determine what means are "necessary and proper" in executing its powers.

![The Federal Bureau of Investigation: History, Powers, and Controversies of the FBI [2 volumes]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91g-bAXvg9L._AC_UY218_.jpg)