Exploring the question what are some political opens the door to a vast array of topics, from ideologies and systems to policies and movements that shape societies worldwide. Politics, at its core, involves the mechanisms through which decisions are made and power is distributed, influencing everything from local communities to global relations. Understanding political structures, such as democracies, authoritarian regimes, or hybrid systems, provides insight into how governance operates and how citizens engage with their leaders. Additionally, political issues like economic inequality, climate change, and human rights often dominate public discourse, reflecting the diverse challenges and priorities that define contemporary political landscapes. By examining these facets, one can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities and implications of political systems and their impact on daily life.

What You'll Learn

What are some political ideologies?

Political ideologies are the lenses through which societies interpret power, governance, and the common good. At their core, they offer frameworks for organizing communities, allocating resources, and resolving conflicts. Liberalism, for instance, champions individual freedoms and free markets, often emphasizing limited government intervention. This ideology has shaped democracies worldwide, from the United States to Western Europe, where it underpins constitutional rights and capitalist economies. However, its focus on personal liberty can sometimes clash with collective needs, such as social welfare or environmental protection, revealing both its strengths and limitations.

Contrastingly, socialism prioritizes collective ownership and equitable distribution of resources. Emerging as a response to industrial-era exploitation, it advocates for public control of key industries and robust social safety nets. Countries like Sweden and Norway exemplify democratic socialism, blending market economies with extensive welfare systems. Yet, critics argue that centralized planning can stifle innovation and economic growth, highlighting the tension between equality and efficiency. Understanding socialism requires examining its historical context and modern adaptations, as it continues to influence labor rights, healthcare policies, and wealth redistribution debates.

Conservatism, another major ideology, emphasizes tradition, stability, and gradual change. Rooted in preserving established institutions, it often resists radical reforms in favor of maintaining social order. In the United States, conservatism manifests in support for limited government, free markets, and cultural traditionalism. However, its focus on the past can sometimes hinder progress on issues like climate change or social justice. To engage with conservatism, consider its role in balancing innovation with continuity, and how it adapts to modern challenges while staying true to its core principles.

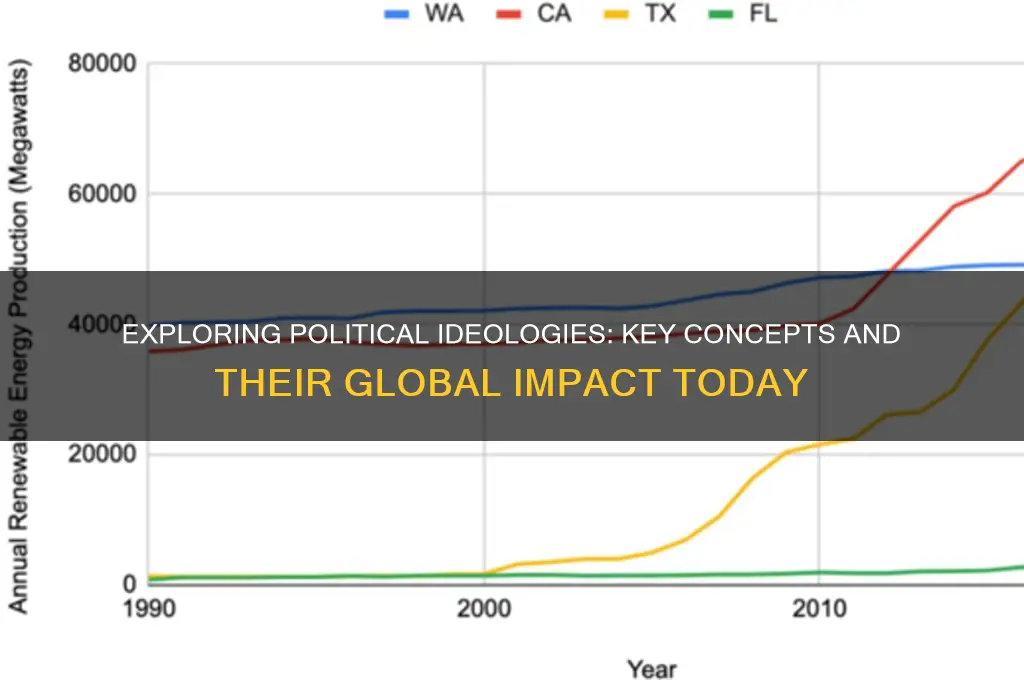

Meanwhile, environmentalism has emerged as a political ideology centered on sustainability and ecological preservation. Unlike traditional ideologies, it transcends left-right divides, advocating for policies that prioritize planetary health over economic growth. Movements like the Green Party in Germany or the Sunrise Movement in the U.S. push for renewable energy, conservation, and climate justice. Practical steps for individuals include reducing carbon footprints, supporting green policies, and advocating for systemic change. Environmentalism challenges societies to rethink progress, urging a shift from consumption-driven models to regenerative practices.

Finally, anarchism rejects all forms of hierarchical authority, envisioning a stateless society based on voluntary cooperation. While often misunderstood as chaos, it encompasses diverse schools of thought, from anarcho-communism to anarcho-capitalism. Historical examples include the Spanish Revolution of 1936, where anarchist communities operated without central governance. Though rarely implemented on a large scale, anarchism’s critique of power structures offers valuable insights into decentralization and grassroots organizing. Its principles encourage questioning authority and exploring alternatives to traditional governance models.

Each ideology reflects distinct values and visions for society, shaping policies, cultures, and global dynamics. By examining their tenets, historical contexts, and modern applications, one can better navigate the complexities of political discourse and contribute to informed, constructive dialogue.

Was Machiavelli's Political Fame Justified? Exploring His Enduring Legacy

You may want to see also

What are some political systems globally?

Political systems globally exhibit a diverse array of structures, each shaped by historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors. One prominent example is democracy, which exists in various forms such as representative democracy (e.g., the United States) and parliamentary democracy (e.g., Germany). In representative democracies, citizens elect officials to make decisions on their behalf, while parliamentary systems often feature a fusion of executive and legislative powers. Despite their differences, both models emphasize citizen participation and accountability, though they can struggle with issues like polarization and slow decision-making.

In contrast, authoritarian regimes (e.g., China, North Korea) centralize power in a single party or leader, often limiting political freedoms and dissent. These systems prioritize stability and rapid decision-making but frequently face criticism for human rights abuses and lack of transparency. A key distinction lies in their approach to governance: while democracies rely on checks and balances, authoritarian systems often operate without meaningful constraints. For those studying political systems, understanding this trade-off between efficiency and liberty is crucial.

Monarchies, though less common today, still exist in both ceremonial (e.g., the United Kingdom) and absolute forms (e.g., Saudi Arabia). Ceremonial monarchies retain symbolic roles, with real power vested in elected governments, while absolute monarchies grant the ruler unchecked authority. Analyzing these systems highlights the spectrum of power distribution and the role of tradition in modern governance. For instance, the UK’s monarchy serves as a cultural anchor, while Saudi Arabia’s monarchy wields significant political and economic control.

Hybrid systems, such as semi-presidential republics (e.g., France), combine elements of presidential and parliamentary models. In France, both a president and a prime minister share executive powers, creating a dual authority structure. This system aims to balance efficiency and representation but can lead to power struggles. For practitioners in political science, examining hybrids reveals the complexities of designing governance frameworks that adapt to diverse societal needs.

Lastly, theocratic systems (e.g., Iran) integrate religious doctrine into governance, often blurring the line between spiritual and political authority. In Iran, the Supreme Leader holds ultimate power, guided by Islamic principles. This model underscores the influence of religion on political structures, though it raises questions about inclusivity and secularism. When evaluating theocratic systems, consider how they navigate modern challenges while maintaining religious fidelity.

Each political system reflects unique priorities and trade-offs, offering valuable insights for policymakers, scholars, and citizens alike. By studying these models, one can better understand the mechanisms of governance and their impact on societies worldwide.

Does Money Buy Political Support? Exploring the Influence of Wealth

You may want to see also

What are some political scandals in history?

Political scandals have long shaped public perception, toppled leaders, and altered the course of history. One of the most infamous examples is the Watergate scandal (1972–1974), which forced U.S. President Richard Nixon to resign. It began with a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex and unraveled into a web of illegal surveillance, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power. The scandal not only ended Nixon’s presidency but also set a precedent for investigative journalism, as reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein exposed the truth. This case underscores how unchecked authority can erode democratic institutions, leaving a lasting impact on political accountability.

In contrast, the Profumo Affair (1961–1963) in the United Kingdom illustrates how personal indiscretions can escalate into national crises. Secretary of State for War John Profumo lied to Parliament about his affair with Christine Keeler, who was also involved with a Soviet naval attaché. The scandal threatened national security and exposed vulnerabilities in government integrity. It led to Profumo’s resignation and damaged the Conservative Party’s reputation. This example highlights the intersection of private morality and public trust, revealing how personal failings can have far-reaching political consequences.

Another notable scandal is Teapot Dome (1922–1924) in the United States, which involved Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall leasing federal oil reserves to private companies in exchange for bribes. Fall became the first U.S. cabinet member to be imprisoned for actions in office. This scandal exposed systemic corruption in the Harding administration and led to stricter regulations on natural resource management. It serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of collusion between government officials and corporate interests, emphasizing the need for transparency in public service.

Globally, the Lockheed Bribery Scandals (1970s) demonstrated how corruption can transcend borders. The U.S. aerospace company Lockheed admitted to bribing foreign officials in Japan, West Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands to secure aircraft contracts. The fallout included the resignation of Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka and heightened international scrutiny of corporate practices. This scandal revealed the global reach of political corruption and spurred efforts to combat bribery through legislation like the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Finally, the Iran-Contra Affair (1985–1987) showcased how covert operations can undermine democratic processes. U.S. officials secretly sold weapons to Iran, an enemy state, and used the proceeds to fund Contra rebels in Nicaragua, bypassing congressional restrictions. The scandal implicated high-ranking officials, including President Ronald Reagan, and raised questions about executive overreach. It underscored the importance of legislative oversight and the rule of law, reminding citizens that even well-intentioned actions must adhere to constitutional principles.

These scandals, though diverse in nature, share a common thread: they expose the fragility of trust in political systems. From personal misconduct to systemic corruption, each case serves as a reminder that transparency, accountability, and ethical leadership are essential to maintaining public confidence. By studying these historical events, we can better understand the consequences of political malfeasance and work to prevent future abuses of power.

Is Partisanship a Political Label or a Divisive Force?

You may want to see also

What are some political movements shaping societies?

Political movements are the engines of societal transformation, often emerging in response to systemic inequalities, cultural shifts, or technological advancements. One such movement reshaping societies globally is climate activism, driven by the urgency of environmental collapse. Groups like Extinction Rebellion and Fridays for Future, inspired by figures such as Greta Thunberg, have mobilized millions to demand radical policy changes. Their tactics—strikes, protests, and lawsuits—have forced governments and corporations to confront carbon emissions, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. For instance, the European Union’s Green Deal and the rise of carbon pricing policies worldwide are direct outcomes of this pressure. Practical engagement in this movement involves reducing personal carbon footprints, supporting renewable energy initiatives, and advocating for local green policies.

Another pivotal movement is intersectional feminism, which challenges the overlapping systems of oppression faced by women, particularly those marginalized by race, class, or sexuality. Unlike earlier waves of feminism, this movement emphasizes inclusivity and the dismantling of power structures beyond gender alone. Campaigns like #MeToo and #SayHerName have exposed systemic abuses while pushing for legal reforms, workplace equity, and cultural representation. To contribute effectively, individuals can amplify marginalized voices, educate themselves on intersectionality, and support organizations addressing gender-based violence and economic inequality.

The digital rights movement is also redefining societal norms in an increasingly surveillance-driven world. Fueled by revelations like Edward Snowden’s exposure of mass surveillance, this movement advocates for data privacy, net neutrality, and protection against algorithmic bias. Legislation such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) reflects its influence, while grassroots efforts push for transparency in AI systems. Practical steps include using encrypted communication tools, advocating for digital literacy programs, and holding tech companies accountable for ethical practices.

Lastly, decolonization movements are reshaping identities and institutions by confronting the legacies of imperialism. From Indigenous land rights struggles in North America to anti-racism protests in Europe, these movements seek to reclaim histories, languages, and resources. They challenge cultural appropriation, demand reparations, and advocate for curriculum reforms that reflect diverse narratives. Engaging with this movement involves learning about local Indigenous histories, supporting land back initiatives, and promoting media representation that honors marginalized cultures.

Each of these movements demonstrates how political activism translates into tangible societal change, offering pathways for individuals to participate in shaping a more equitable and sustainable future. Their success hinges on collective action, informed advocacy, and the courage to challenge entrenched systems.

Gracefully Declining: How to RSVP No with Tact and Kindness

You may want to see also

What are some political theories on governance?

Political theories on governance are the blueprints that shape how societies organize power, authority, and decision-making. Among the most influential is liberalism, which emphasizes individual freedoms, limited government, and free markets. Rooted in thinkers like John Locke and John Stuart Mill, liberalism argues that governments exist to protect natural rights—life, liberty, and property. Modern liberal democracies, such as the United States and Germany, exemplify this theory, balancing majority rule with minority rights through checks and balances. However, critics argue that unchecked capitalism under liberalism can exacerbate inequality, highlighting its limitations in addressing systemic injustices.

In contrast, socialism and communism propose collective ownership of resources and centralized planning to achieve greater equality. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels laid the groundwork for these theories, critiquing capitalism’s exploitation of the working class. Socialist governments, like those in Scandinavia, implement redistributive policies through taxation and welfare systems, while communist regimes, historically seen in the Soviet Union, aim to abolish class distinctions entirely. The challenge lies in balancing efficiency with equity; centralized control often stifles innovation, and authoritarian tendencies can undermine individual freedoms.

Conservatism offers a third lens, prioritizing tradition, stability, and gradual change. Thinkers like Edmund Burke argue that societies thrive when rooted in established institutions and values. Conservative governance often emphasizes law and order, national identity, and limited government intervention in the economy. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Tory governments have historically championed free markets while preserving monarchical traditions. Critics, however, contend that conservatism resists progress, particularly on issues like social justice and environmental reform.

Finally, anarchism rejects the state entirely, advocating for self-governance and voluntary cooperation. Anarchist thinkers like Mikhail Bakunin and Emma Goldman argue that hierarchical structures inherently oppress individuals. While rarely implemented on a large scale, anarchist principles influence movements like decentralized cooperatives and grassroots activism. The theory’s practicality remains debated, as the absence of centralized authority can lead to chaos in complex societies.

Each of these theories offers distinct prescriptions for governance, reflecting differing priorities—whether individual liberty, economic equality, social stability, or autonomy. Understanding them allows societies to navigate trade-offs and design systems that align with their values, though no single theory provides a perfect solution.

Bridging Divides: Strategies to Overcome Adversarial Politics and Foster Unity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political ideologies include liberalism, conservatism, socialism, communism, fascism, anarchism, environmentalism, and feminism, each with distinct views on governance, economics, and social structures.

Political systems include democracy, monarchy, dictatorship, theocracy, oligarchy, and authoritarianism, varying in how power is distributed and exercised.

Major political parties in the U.S. are the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, with smaller parties like the Libertarian Party and the Green Party also present.

Global political issues include climate change, economic inequality, immigration, healthcare access, human rights, and international conflict.

Proposed political reforms include campaign finance reform, voting rights expansion, term limits for politicians, and changes to electoral systems like ranked-choice voting.